Rama Ranee

|

February 23, 2026

|

12

min read

Raised by nature: Bonds with farms, forests help children grow holistically

Safe spaces, outlets for creativity and curiosity, and a connection to the Earth—nature can mean many things to kids

Read More

Jodhpur’s iconic chilli faces decline as groundwater woes leave farmers in a lurch

Once a lifeline of Rajasthan’s arid landscape, the village of Mathania stood as a beacon of agricultural prosperity. Known for its fiery red chillies and its crucial role in water distribution across the state, Mathania was more than just a village—it was a symbol of sustenance and economic strength. But today, it tells a different story.

Much like Comala in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, Mathania has now become a shadow of its former self since the 1980s. Where bustling farms once painted the land red with chilli fields, parched soil now stretches endlessly, cracked and lifeless. The wells that once nourished entire regions have dried up, leaving behind only the echoes of a past when Mathania dictated the pulse of Rajasthan’s agricultural trade.

Much like Rulfo’s protagonist Juan Preciado’s experience upon entering Comala, visitors to Mathania today are surrounded by silence, broken only by the distant whispers of those who remember its past. But unlike Comala’s ghosts, Mathania’s decline is not a supernatural mystery—it is rooted in exploiting its most precious resource, water. The taste that once defined it, now overpowered by an extra spiciness.

Also read: The tree that keeps the Thar alive

“The Mirch is best known for its role in Rajasthan's famous laal maas,” says Dhani Chand, a local of Mathania village. But its culinary influence doesn’t stop there. “It’s also a staple in chutneys and pickles, adding a depth of flavour that’s hard to match,” he adds. “What truly sets it apart is its mild pungency compared to other chillies, yet it is so rich and addictive that once you start, you won’t want to stop,” says Jodhpur resident Rajesh Dave.

Mathania’s agricultural landscape is undergoing significant shifts due to rapid commercialisation. When the authors of this report visited Mathania to check the cost of powdered chilli, we were taken aback: a single packet sells for a staggering ₹500-₹600. No wonder farmers once made significant profits from its cultivation.

Insaf, a tea shop owner in his fifties, explains that these days chillies from other states [like Andhra Pradesh] often flood the local markets, making it harder for authentic Mathania chillies to compete. “Nowadays, mathania chillies are so expensive that we can’t even afford to consume them,” he adds, seated at his small establishment in the village.

The rising demand for Mathania chillies has put mounting pressure on local farmers, triggering a domino effect of environmental and agricultural challenges. Over-extraction of groundwater to meet production targets has led to severe water scarcity in the region. This, in turn, has stunted the growth of vegetation, reducing the availability of fodder and water for cattle. As livestock numbers declined, so did the production of manure, a crucial input for cultivation further deepening the crisis for farmers and disrupting the delicate balance of the local agro-ecosystem.

The area under red chilli cultivation in Rajasthan has dropped sharply, from a decadal average of 41.5 thousand hectares in 1987–97 to just 12.7 thousand hectares in 2007–17.

Michael Goldman, a sociologist from the University of Minnesota, highlighted this alarming rate of groundwater extraction in the region in his 1988 paper, The “Mirch-Masala” of Chili Peppers: The Production of Drought in the Jodhpur Region of Rajasthan. “Some farmers were extracting as much as 50,000 gallons (of water) per day, irrigating their fields 40 to 60 times over a nine-month growing season,” he writes. This depletion rate, where water extraction far exceeded natural regeneration, stood in stark contrast to the modest 4-10 irrigations per season required for most staple food crops, added Goldman.

Further, to fulfil Jodhpur city's water demand, the state's Public Health Engineering Department in 2001 identified and developed a few potential groundwater sources, including Mathania. Locals say this action by the government authorities has led to severe water shortage for irrigation, crippling chilli production and drastically altering the village’s agricultural landscape. “There is no water for irrigation in the village,” says 49-year-old Mahinder, a resident of Mathania. “Farmers are increasingly shifting to cash crops like ajwain and jeera [cumin] to sustain their livelihoods, since growing chillies in the fields demands considerable irrigation.”

Mathania chilli business is seasonal, with the harvesting cycle beginning in August, when farmers sow the seeds, and culminating at the end of February or March, when the chillies are harvested. Low temperature is one of the necessary conditions for Mathania chillies, which is why the harvest cycle is winter-dominated.

As per a research paper, Changes in cropping pattern in Rajasthan: 1957 to 2017, the area under red chilli cultivation in Rajasthan has dropped sharply, from a decadal average of 41.5 thousand hectares in 1987–97 to just 12.7 thousand hectares in 2007–17. In contrast, cumin cultivation has surged more than eightfold during the same period, rising from 37.8 to 328.8 thousand hectares. Similar increases are seen for other spices like fenugreek, coriander, and ajwain, reflecting a broader shift in cropping patterns as farmers adapt to water scarcity and changing economic realities.

Also read: Inside one of India’s biggest mango markets

Shifting climate patterns are also increasingly affecting Mathania's agricultural landscape since the 1980s. From 1984 to 1988, the severe drought brought Rajasthan to its knees, leaving 7,942 villages, including Mathania, without a structured water supply, according to Goldman’s paper.

As per research by the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, chilli can be grown successfully as a rain-fed crop in areas receiving an annual rainfall of 850–1200 mm. However, Jodhpur, where Mathania is located receives only around 323 mm of rainfall annually. The region's annual rainfall, fluctuating between 5 and 20 inches, has proved insufficient for the sandy soils that retain little moisture. Groundwater, crucial to life in this desert expanse, is often saline or brackish and can lie buried up to 600 metres beneath the earth.

Between 1975 and 1986, chilli production in Jodhpur district surged from 5,700 tonnes to 14,600 tonnes, with the cultivated area expanding from 5,830 to 10,860 hectares. Yields also increased from 9.5 to 13.67 quintals per hectare, but this growth came at a cost. Chilli farming demanded frequent irrigation, exacerbating groundwater depletion.

Ajmal Dhaka, a farmer from Jodhpur, described the immense water demands of Mathania chilli cultivation. “Over four months, an acre of land needs to be irrigated 12-14 times,” Dhaka says.

Farmers constructed frames to hold water to meet this need, ensuring the plants received adequate water. This labour-intensive method underscores the water dependency of these vibrant red chillies. The ideal amount of rainfall needed for these chillies to grow is around 850-1200 mm.

A report by the Central Ground Water Board in 2023 confirmed a continued decline in groundwater levels, noting a drop of 1.2 metres annually over the past decade. The Rajasthan State Action Plan on Climate Change (SAPCC) in 2022 further predicted heightened water stress due to erratic rainfall and prolonged dry spells in the coming years.

The most affluent Mathania chilli producers claim to maintain a steady 50 per cent profit rate, despite the rising costs of agricultural inputs. However, ecological degradation has intensified these challenges.

One significant factor is the depletion of organic manure, a vital input for chilli farming on the region’s sandy soils. “With the advent of chemical fertilisers, the quality and taste are changing,” says 37-year-old Manga Ram, one of the farmers.

The loss of ground vegetation, including grasses, shrubs, trees and common pastures, has led to the mass starvation of cattle, reducing the local livestock population by nearly half over the past four years.

With fewer cattle, farmers face a scarcity of organic manure, forcing them to rely on chemical fertilisers. However, improper use of these fertilisers has exacerbated soil degradation. Lacking the technical knowledge for balanced application, many farmers inadvertently harm their fields, further lowering yields and profitability.

Also read: The world is going nuts about makhanas

Agriculture has long defined Mathania's identity, especially its renowned chilli pepper. However, the shift from rain-fed crops like jowar, bajra, pulses, and oilseeds to intensive chilli cultivation placed immense pressure on the region’s water reserves.

One major factor is Anthracnose, a plant disease that causes leaves to curl and twist into a condition often called “leaf curl”.

The decline of the Mathania Mirch is not just a story of water scarcity—it is a complex crisis with multiple factors at play. “The degradation of underground water quality has significantly reduced production,” says Dr. Rahul Bhardwaj, an assistant professor at the Agriculture University of Jodhpur. But water alone isn’t the culprit. He outlines challenges that have pushed this once-thriving chilli to the brink. One major factor is Anthracnose, a plant disease that causes leaves to curl and twist into a condition often called “leaf curl”. Bhardwaj explains that this disease has severely impacted chilli farming, weakening plants and reducing yields. But the problems don’t stop with diseases.

The unorganised chilli market of Rajasthan has further dented production. “Because of the lack of a structured market, there is no consistent demand. Many farmers have abandoned chilli farming, and with competition from chillies like Guntur Mirchi from Andhra Pradesh, the situation has worsened,” says Bhardwaj.

It leaves local farmers without protection or incentives. “Without structured intervention, cheaper chillies from other regions flood the market, falsely labelled Mathania Mirch, and erode its authenticity,” mentions one farmer.

However, the situation for this traditional crop may change through the bid for a geographical indication (GI) tag. As per a News18 report, an application by a farmer producer organisation (FPO) named Tinwari Farmer Producer Company, supported by the National Bank for Rural Development (NABARD), has been accepted by the GI Registry and is now in the objection phase.

This step is crucial because rising demand has pressured farmers to overuse groundwater, causing water scarcity, loss of livestock, and lower manure availability—all hurting farming and the local environment. The GI tag could help restore balance and secure farmers' rights.

When we asked Bhardwaj about any solutions provided by the Jodhpur’s Agricultural University, he explained, "We have developed RCH1 hybrid seeds, which are slightly different from the original, with a little more pungency and shorter in height. These seeds are offered to interested farmers. However, there are still very few farmers who are willing to adopt these new hybrid seeds." In addition to these factors, when we inquired about cross-pollination, Bhardwaj mentioned, "Cross-pollination is less than 30 per cent, which is not significant in Mathania Mirch."

{{quiz}}

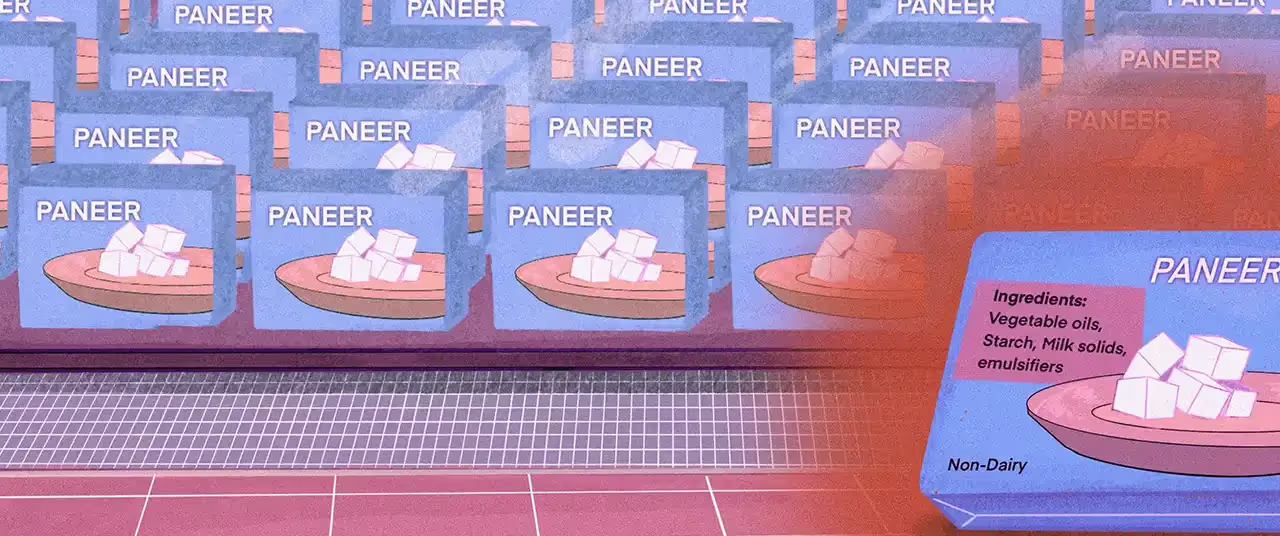

What analogue paneer means for your health, and how to spot it

Paneer holds a cherished place in the Indian diet. For many, it’s not just a delicacy but also a versatile staple—a reliable source of protein that seamlessly fits into both everyday meals and special festive spreads. Think about it: this dependable cheese makes for a rich addition to curries, a great centrepiece as appetizers and also softly crumbles its way into the stuffings for rolls, burger patties, and koftas. Paneer also happens to be, often, the first choice for vegetarians who want to consume a hearty alternative to meat–it’s perfect for those particular about meeting their protein intake in a meat-free diet. Paneer has also come under the scanner for being an extremely adulterated product in the Indian market.

Recently there’s been a new kid on the block: analogue paneer. Experts and social media users have raised an alarm over how this imitation product is often sold to unknowing consumers as real, fresh paneer.

What exactly are we eating, and how is analogue paneer different from the real thing?

According to the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), dairy “analogues” are products where milk constituents are replaced wholly or partly with non-dairy ingredients. The end product is designed to look, feel, and act like the original.

Milk-based paneer–the kind we make at home, or buy from local dairies or dairy companies–is made by curdling milk with an acid (like lemon juice or vinegar). The curds are separated from the whey, and pressed into the all-familiar paneer block.

Analogue paneer, on the other hand, uses a cocktail of vegetable oils, starch, milk solids, and emulsifiers—less cow, more chemistry. Here’s the thing: to make real paneer, whole milk with lots of good fat is used, because paneer is about 20-25% fat, and this is what gives this cheese its rich, buttery texture. To imitate it, you need an oil that solidifies at room temperature, much like milk fat or butter…but of course, cheaper. That’s where vegetable oils like palm oil come into play. This oil is mixed with milk solids to mimic the milk fat and milk protein combination; emulsifiers help blend this oil with water and other moisture, and then starch is added to this mix, to mimic the firm texture of paneer, as well as make sure that this product holds structure when heated or cooked.

But even with these extra ingredients, analogue paneer is cheaper than the real deal. Much cheaper!

A kilo of real paneer might cost around ₹400. Analogue paneer? About ₹200–250. That 50% discount comes with ingredients that are far more budget-friendly—and sometimes, body-unfriendly too.

Also read: AI or A2? India’s milk dilemma explained

At first glance, slabs of real and imitation paneer may look identical. But when it comes to nutrients, they’re not even close. Real paneer packs approximately 18–20g of protein per 100g. Analogue paneer often falls short, delivering only 7–10g, depending on its formula. For vegetarians who rely on paneer to fill their protein intake, this swap could mean a slow deficit over time.

Another serious concern, when it comes to analogue paneer, is trans fats. Real paneer contains 20–25g of fat—mostly natural saturated fats. Analogue paneer has 15–20g, but here's the catch: a significant portion of it can be trans fat—the type linked to heart disease, diabetes, and bad cholesterol levels (LDL). This is because to mimic the nature of milk fat, which stays solid at room temperature (think about butter in your cool kitchen), manufacturers need to use hydrogenated vegetable oil–a variant which introduces a lot of trans fats into the oil. Other than this, analogue paneer can also cause bloating, acidity, nausea, and even diarrhoea.

.avif)

Also read: Whey to go: A complete guide to protein

If you're shopping for packaged and branded paneer, be sure to check the label. FSSAI mandates manufacturers to either declare the word “analogue” on the paneer packet, or at least print the phrases “Contains oil (or other substitutes)” or “Contains no milk.” It’s good to be cautious: analogue paneer packets may not even contain the word–but they will always have an ingredient list. Check the list to see if instead of milk fat, you see vegetable oil and starch. Real paneer’s ingredient list will not have these constituents.

Analogue paneer will also cost less—if it's too good to be paneer, it probably isn't. If a paneer dish in a restaurant, or a packet of unbranded paneer in a store costs much less than usual, you can ask the chef or the shop owner for a clarification.

Already have some paneer at home? Here's how to play detective:

Restaurant food is, of course, tougher to test. There is one trick: press the paneer between your fingers. Real paneer holds its shape when mashed gently. Analogue paneer, on the other hand, crumbles very quickly.

Also read: Detox teas: Slim claims, heavy consequences

The debate over “fake” dairy products isn’t a new one. The use of vegetable oils in “frozen desserts” has also come under the scanner before–in fact, “frozen desserts” is also a regulated analogue dairy product.

However, the question still remains: are analogue paneer and frozen desserts merely products on offer, or a deliberate effort by giant corporations to deceive consumers? The words “analogue paneer” or “non-dairy” may be very easy to spot on labels in kirana stores, supermarkets and quick commerce apps, but these labels are entirely missing in restaurant menus. Even though they are required to, many restaurants don’t disclose their usage of analogue paneer over dairy paneer to achieve higher profit margins.

Moreover, India isn’t a label-sensitive market. Although consumers may read labels, a survey conducted by the National Institute of Nutrition across five cities found that this is mostly to look at brand names and expiry dates. In fact, only 9% of those surveyed made sure to read the nutritional value index (which includes sugar, fats, trans fat, calories, carbohydrates, protein) every single time. 28% of the group read it sometimes, and 63% didn’t read it at all. Where India is sensitive, is price. Paneer is generally considered an expensive ingredient, which is why analogue paneer has emerged as a popular alternative for those players who believe it can serve the same purpose as an ingredient.

Analogue paneer also poses a threat to dairy farmers. When the consumer can so easily confuse milk-based paneer for analogue paneer, it forces dairy farmers to enter into an unfair price competition with the makers of its analogue counterpart.

The rise of wellness culture in India has seen the Indian consumer become more and more interested in what they are consuming. In order for the paneer segment to serve this consumer fairly, manufacturers, FMCG giants and restaurants must commit to transparency, ensuring that those who opt for analogue paneer are doing so purposefully and with awareness.

{{quiz}}

Solar tech is helping farmers in remote Meghalaya grow, process and protect their produce efficiently

On a balmy February morning, white clouds hung over Pherlin Ripnar’s farmland spread across two hectares of land in Patharkhmah village of Ri-Bhoi district in Meghalaya. Inside one of the polyhouses, Ripnar carefully looked at his mushroom cultivation—most of the mushrooms had emerged from the substrate. “These will be ready to be sold in the market in the next 2-3 days,” Ripnar says.

In Ripnar’s village, there are frequent power cuts, but he has been able to continue farming thanks to the solar panels installed on his farmland.

Ripnar learned the ropes of farming from his father when he was young. Growing up with 13 siblings, he had to contribute as an extra hand to support his parents. After finishing class 12 as an arts student, he opened a small paan shop in his village to earn a living. When he was around 28 years old, he met the founders of MOSONiE—a non-profit that works in the Ri-Bhoi district of Meghalaya—who encouraged and motivated Ripnar to adopt sustainable solutions for livelihoods.

With the help of MOSONiE and Selco Foundation—a large solar non-profit—Ripnar started a small solar-powered photocopy and printing business in the same place where he used to run his paan shop. “Electricity is a big problem in our village. We are sometimes without it for days,” the now 38-year-old Ripnar says. (MOSONiE and Selco Foundation have also been key to helping Pherlin and his peers access devices like solar panels and solar-powered rice hullers.)

Also read: No monkeying around on this kiwi farm

Ripnar’s interest has always been agriculture, so he continued to practice organic farming at home on his land. In 2023, he bought his current land from his cousin sister on lease, to begin working on a larger scale.

As Ripnar has been using solar technology for about a decade now, he knows how solar panels can help him and his farm compensate for days without electricity. Ripnar explains that the solar panels give the farm an uninterrupted electricity supply. He also does not have to use torchlights, mobile phones and candles at night to check on his farm. As the farm is isolated, Ripnar installed three street lights on the uphill pathway that leads to it in 2023. The solar panels ensure that these street lights also operate throughout the night. “Solar-powered lighting can better protect farms from wild animal attacks and thefts,” Ripnar notes.

It also means Ripnar and the caretaker in his room have more consistent electricity. This helps them have a good night's sleep after a hard day at work. “We feel comfortable,” he says.

{{marquee}}

The farmer has also been using solar dryers to dry vegetables, grains and fish. “We grow a lot of ginger and turmeric here to make pickles, or to sell in the market. I used the dryer mainly to dry ginger and turmeric,” he says. Solar dryers help preserve agricultural products for longer periods, reducing the risk of spoilage and waste post-harvest.

MOSONiE, run by a group of women from northeast India, has been linking farmers with banks and other lenders, such as non-banking financial companies, for financial assistance in purchasing solar panels and other solar-powered machines.

With the help of MOSONiE, Ripnar took a loan from the Meghalaya Rural Bank (MRB) in 2019, which he has now repaid, to install the solar panels in his farm. “I was also able to purchase solar batteries (which can help store sunlight during the day),” Ripnar adds.

On his farm, Ripnar grows local brown maize, paddy, and three varieties of pumpkins, yams, mushrooms, tomatoes, lettuce, cabbage and other vegetables. He said that with support from the Government of Meghalaya’s Horticulture Department, he is also growing orchids inside the polyhouses, which has been profitable.

Also read: This farmer builds his own tools—and upskills others, too

Solar is a fast-growing, useful and cost-effective option for addressing electricity challenges, especially in Meghalaya's remote, hilly and forested areas, where the electricity supply can be erratic. “Solar energy can help farmers in various ways by powering their farm equipment and appliances,” says Ringbila Pungding, one of the co-founders of MOSONiE. “We support farmers like Pherlin by identifying their needs and challenges, and tailoring solutions to meet their specific energy requirements,” Pungding adds.

Ioanis Kurbah from Nartap village in the Ri-Bhoi district of Meghalaya is another case. Kurbah has been using a solar-powered rice huller machine since 2022. These machines are capable of cleaning, husking, polishing, grading and managing rice and its by-products. “Earlier, I was involved in cultivating paddy, bamboo and broom grass. But now I have moved on to managing the rice huller machine in my village,” says Kurbah.

Every household in Nartap village is engaged in paddy farming, and most of the farmers were using the old machine, which ran on diesel, required more water and wasn’t eco-friendly, Kurbah noted. “It is also very costly, makes a lot of noise, produces dust, and affects the health of those who operate the machines. Besides, the machine could simply grind the paddy—it could not separate the husk from the rice. Farmers need to return home and remove the husk from the rice, which requires about 3 to 4 hours,” Kurbah explains.

Out of 92 households, about 85 families now get their rice processed through Kurbah’s solar-powered rice huller machine. “The farmers are absolutely happy, and I, too, can support my family now,” Kurbah says.

Kurbah adds that even to run his poultry farm, “We need constant electricity. Our area is extremely prone to frequent power cuts. During summer, electricity is gone for a week or so. Solar panels help us manage the poultry farm, which needs to be cleaned regularly, and chickens need to be fed food and medicines.” He said that his poultry farm now runs entirely with the help of two solar panels, which have been a lifesaver for him.

Also read: One Odisha woman’s mission to preserve taste, tradition through seeds

Nagesh Rao, a senior programme manager at Selco Foundation, explains how many farmers post-harvest depend on selling the raw materials directly in the market. “Sometimes, if they don’t have the means to process the raw material, they give it at a throwaway price. With the solar-enabled rice huller machines, they can process the paddy and sell it at a higher margin. The machine helps them access energy at their doorstep without depending on other sources for electricity.”

According to Binit Das, programme manager, renewable energy unit at the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi, solar technology could help farmers from the effects of climate change in mountainous states like Meghalaya. “When it comes to electricity, people staying far away from cities and towns face many transmission and distribution challenges. In case of extreme weather events like landslides and heavy rainfall, the centralised available sources of power will get affected, which will then impact the day-to-day lives of farmers and their families,” Das says, adding that decentralised renewable energy (DRE) can be a game changer for communities who live in remote areas. “If DRE is made available for communities, then there will be less impact from extreme weather events.”

In Patharkhmah village, when asked what kind of facilities might help farmers in Meghalaya, Ripnar laments how there are no review meetings that farmers can have with the government’s agriculture and horticulture departments and banks regarding loans, schemes and subsidies. “If the government can conduct monthly review meetings with our farmers to share grievances, especially for those in remote areas of the state, it could benefit us.”

But, for now, Ripnar says he is just thankful that he and his farm have constant access to lighting.

{{quiz}}

Chennai-based Seerakku is turning farmland into carbon sinks by planting trees that supplement farmer incomes

Before his stint at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT-Madras), before fatherhood, and before agroforestry became his everyday pursuit, Dinesh SP—like many of us—was clueless about carbon emissions at an individual level, and the long shadow they cast. Once he became aware about their impact on the environment, however, life would never be the same. First, he calculated his own emissions using the United Nations carbon footprint calculator.

Alarmed by the number before his eyes, Dinesh committed to making the switch to eco-friendly ways and means. Better yet, he decided to offset his emissions voluntarily and those of his soon-to-be-born daughter, Aadavi. The approach he picked? Planting trees.

In 2022, Dinesh resigned from his position at IIT-M and, after thoughtful discussions with his wife, Janaganandhini, they decided to plant trees on farmland. They chose Janaganandhini’s native village, Sivalingapuram—a rain-fed area near Krishnagiri in Tamil Nadu—as their starting point. Aware of the mistrust among small landholding farmers due to previous experiences with fraudulent schemes, they began by persuading 15 of Nandhini’s relatives to participate in the first plantation drive. Dinesh sourced saplings from local nurseries, selecting native, low-maintenance, and commercially viable species to help landowners generate supplementary income.

In September 2022, six months before the birth of his daughter Aadavi, Dinesh began planting trees. By March 2023, when she was born, he had planted 6,000 trees—including teak, chikoo, mango, lime, sandalwood, coconut, areca nut, and guava—at a density of 300-800 trees per acre. Following consultations with tree-planting experts and organisations, he selected saplings suited to the local ecology, and proximate to water sources. They were planted at 10-foot intervals between crops to avoid disrupting the existing agricultural cycle.

On average, an individual’s annual carbon emissions amount to approximately 3 to 4 tonnes. This figure is calculated by accounting for electricity consumption, dietary habits, and transportation-related emissions. During the initial two years, each tree absorbs only 5 kilograms of carbon, amounting to a total of 30 tonnes over that period. As the trees mature, their carbon absorption capacity increases significantly. These calculations are validated by the UN calculator and are consistent with other recognised international standards.

Beyond Sustainability, a carbon emission audit firm in Coimbatore, reviewed the tree-planting records and confirmed that Aadavi’s lifetime emissions had already been offset. To acknowledge Dinesh’s achievement, the United Nations Sustainable Development Council conducted a survey and validated the records for the Asia Book of Records, which recognised Aadavi as the world’s first carbon-neutral baby in 2024.

Looking to scale the model, Dinesh initially partnered with hospitals in Chennai, planting a tree for every newborn. Media coverage led to individuals approaching him to offset their children’s emissions, while some organisations sought similar efforts as part of their ESG commitments.

In response, Dinesh and Janaganandhini founded Seerakku in 2022—a Chennai-based NGO dedicated to carbon-neutral initiatives through agroforestry. Rather than purchasing seeds, Seerakku sourced them from farmers across Tamil Nadu, raised saplings, and transplanted them at designated sites.

Also read: The tree that keeps the Thar alive

Seerakku’s interest lies with small landholding farmers, who owned even up to 10 acres of land but worked for other, bigger landowners, and invested their earnings in farming—especially in areas like Krishnagiri, where farming is carried out for only six months a year. Their extent of cultivation depended on the financial resources they had. They left the rest of the land barren. In fact, out of the 4 lakh trees Dinesh and his team have planted so far, working with more than 500 farmers, 3 lakh are in Krishnagiri and 1 lakh of them are spread in Tiruvallur, Chengelpet, Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu, and Chithoor in Andhra Pradesh.

Seerakku approached the farmers, and after getting their consent, the team planted the saplings on their lands. In the first two years, Seerakku’s local team visited the plantation sites, checked on the plants, and offered guidance on maintenance. Farm equipment such as tillers, brush-cutters, weeding machines, and natural fertilisers were given to farmers free of cost or on daily or hourly rentals.

Team Seerakku has planted about 2,500 areca nut, coconut, rose apple and lemon trees on the three acres owned by Panchali, a 45-year-old farmer in Sivalingapuram. After her husband’s passing, Panchali and her two children have been living off the income from farming. “Like others around here, I was confined to cultivating ragi and paddy, along with pigeon peas and fava beans for rotational purposes. All these years, we were struggling to recover our initial investment. Now, the lemon trees planted by Seerakku are getting ready for harvest. We expect at least ₹2 lakh in a year as additional income from them,” Panchali says.

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

Income from Seerakku’s agroforestry initiative can range from ₹1 lakh to ₹3 lakhs, depending on the tree species and harvest cycles—for instance, lemon trees bear fruit year-round, while mangoes are seasonal.

In Sivalingapuram, the NGO has planted a total of 2,000 areca nut, lime, and guava trees on farmer Sakthivel’s 6-acre plot. “I’ve already begun harvesting guavas, yielding around 40 kilos a month, which I sell locally for ₹8,000 to ₹10,000. This will increase once the lime trees begin fruiting,” he says.

“Agroforestry benefits farmers without disrupting their primary crops. The additional income strengthens livelihoods and discourages the conversion of farmland into residential or commercial plots. With the right intellectual and financial support, farmers can adopt it successfully,” notes Dinesh.

{{quiz}}

Some of the farmers the organisation encounters are dedicated agriculturists who have fought the odds to persist. This, in turn, can shape their perspective towards agroforestry missions. “It is very difficult to get farmers’ consent and cooperation to get work done on the trees,” Dinesh says.

When it comes to executing Seerakku’s objectives, pest attacks that turn the trees’ leaves yellow and delay fruiting are widespread. Dinesh explains this as one of the predominant challenges the team faces and deals with. Bio-remedies, from neem sprays and meen amilam or fish amino acid (for growth regulation) to neem oil cakes as natural compost for plants, are recommended to control attacks. For those low-income farmers who cannot spend, the team pitches in and takes care of pest prevention.

However, the impact of climate change has taken more severe forms. The team observed that the soil had lost its biodiversity and fertility in several areas, and water sources were inaccessible. In response, they began creating farm ponds across 10-20 cents of land in affected villages. Additionally, disused water bodies—often turned into garbage pits—are now being cleared to allow rainwater to percolate and help recharge depleted water tables. Drip irrigation systems have also been installed across farmland.

What a nature-conscious solution to a primate problem tells us about Mandeep Verma’s farming philosophy

When Mandeep Verma, a former marketing professional, left behind his lucrative career at Wipro in Delhi and moved to Himachal Pradesh in 2015 to start farming, he expected challenges to come his way—challenges that are typical of Indian agriculture. What he didn’t expect was that one of the biggest hindrances he would face would be monkeys (rhesus macaques) and langurs. “The monkey menace,” he calls it. No plant being grown in the area is safe—from maize to potato and tomato, monkeys eat all of it and harm every plant.

Verma’s journey started with a simple wish—to move back to his hometown of Shili, a small village in the Solan district so that he could be close to his parents, and so his kids could grow up in humble surroundings with clean air, fresh water and a thriving environment. He returned to the roughly 41 bighas (1 bigha is about 0.619 acres, making the land 8.199 acres) of barren land he owned in his village. Even as he started cultivating and working on the land, with an initial investment of ₹4 lakh, he was greeted by monkeys destroying his saplings. “It’s a widespread problem in Himachal,” he says. “Some people rely on solar fencing. It gives a mild shock to the animals, but they don’t die. Other people even poison the monkeys, but that’s not good. We shouldn’t be killing other creatures for our benefit,” he adds.

He started researching, looking for alternative crops that would be safe from the monkeys. His search led him to Dr. Vishal Rana at the Department of Fruit Science at the Dr. Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture & Forestry in Himachal Pradesh, who encouraged him to grow kiwis. “When it [the kiwi fruit] is harvested, it is hard and very, very bitter,” says Dr. Rana. It also has a spiky, hairy texture outside, which deters the monkeys from repeatedly plucking it. Besides tackling the monkey problem, kiwis also make for a practical choice, since they don’t require any specific packaging and transporting them doesn't require any special provisions. Dr. Rana explains that once ready, they remain ripe for about 10 days, giving farmers plenty of time to market them, within India or abroad. “In terms of water, temperature and soil, kiwis were a good fit for the farm,” says Verma, who grows the Allison and Hayward varieties on his farm.

{{marquee}}

In 2015, Verma started with 150 kiwi plants, observing, for a year, how they respond to the environment and then planting more over time. Over the last decade, he kept adding plants; today, his farm has 1,000 of them, all at different stages of development. Since kiwis are seasonal, as a way of diversifying his business, he also started growing apples, because they are quick in production, giving fruit within a year of being planted. He did this in a high-density farming model; the saplings are placed close to each other on the farm, as a way to increase yield without requiring more land. Besides entering the ecotourism space to grow his earnings further, he’s also got a nursery that adds to the revenue.

However, making peace with monkeys is only one aspect of Verma’s larger mission with the farm, named Swaastik Farms (meaning “wellbeing”). The tagline of his venture is ‘growing responsibly,’ which emphasises the central tenet of his mission.

Also read: Why neem oil is the OG pest buster

This kiwi model, which so effectively prevents monkeys from destroying farm plants, has, over time, been adopted by several farmers in the area. While other states of India also grow kiwis, Himachal quickly became a forerunner. Some of the farmers have also formed a collective, planting fruit trees such as pomegranates, apricots, and plums within the forest. Their reasoning is that if the monkeys find food in the forest itself, they’ll be less likely to stray onto the farms. In this manner, kiwis are helping farmers settle a longstanding human-animal conflict in the region.

However, making peace with monkeys is only one aspect of Verma’s larger mission with the farm, named Swaastik Farms (meaning “wellbeing”). The tagline of his venture is ‘growing responsibly,’ which emphasises the central tenet of his mission. The farm has 100% organic cultivation and focuses on natural farming, so much so that 95% of what goes into the farm comes from the farm itself. “Because of the farm, my children are eating healthy. So I thought that the food that goes into the markets should also be healthy. The elderly, children, pregnant women—everyone should be able to consume it,” he says.

Also read: The 'plant' doctor will see you now

In this vein, the plants on the farm are grown without any chemicals. Not using insecticides, for instance, means that no insects are being killed. The farmers aren’t forced to use the chemicals, which they would inevitably inhale, and that would then lead to their health deteriorating. This also means that Verma is allowing nature to work its magic. Just one such instance is the ladybugs roaming around on the farm. They automatically check the mite population, keeping the plants safe. “It’s a responsible process. We’re not polluting the soil, water or air with those chemicals,” he says.

{{quiz}}

Instead of using fertilisers or other chemicals, Verma uses naturally-made concoctions to support the plants on his farm. One is called jiva amrit, which is poured onto the soil. To make a 200-litre container of the mix, one needs 10 kilograms of cow dung, 6-8 litres of cow urine, besan (gram flour) for protein, 2 kilograms of jaggery and 200 grams of soil from under or near a tree. “The soil is not dead matter. It has millions of microorganisms. And the microbial activity in the soil is higher around healthy plants. So we take soil for the jiva amrit from there,” he says. This mix is left to ferment for 4-6 days when the microbial count multiplies manifold. They then use spray pumps to shower the farm with the healthy mix. The high microbial count naturally controls diseases and provides nutrition to the plants. “It makes the soil soft since there’s more aeration and less water logging. So there’s no need for chemical fertilisers,” he explains.

These natural methods lead to healthier fruits with longer shelf lives, and many young people are inspired by Verma’s model and seek to emulate it on their land, too. Even as he helps the farmers around him, Verma envisions a revolution where people return to their roots and take to farming again, now that technology has simplified and democratised access to knowledge.

Also read: Peeling profits: Punjab’s kinnow farmers in crisis

Rajasthan-based Ghoomar sees tribal women as stakeholders with wisdom about forest produce and how to sustainably collect it

In the foothills of the Aravalli range, sitafal (custard apple) has always grown abundantly. Specifically, in the Bali block of Pali district, Rajasthan–where the women of the Garasia tribe have always collected these sweet, fleshy fruits. In fact, custard apples are one of the most abundant non-timber forest produce (NTFP) in the country–they are, in large parts, harvested from forests by communities like the Garasias, who then sell it to processing units or traders and markets. Rajasthan ranks eighth in custard apple production in India. Almost 5000 tons of India’s custard apples came from this state, in 2024.

In the last few years, a quiet but significant churn has been afoot in these remote villages and forests.

Earlier, an adivasi woman had to sell her produce at a throwaway price to the nearest buyer, earning nearly nothing in exchange for collecting the fruits from forests and hills. But now, she has a much higher chance of getting a fair price for her labour, adding significantly to her income.

This difference exists because there is now a producer company in this region—the Ghoomar Mahila Producer Company Ltd, which was established in 2015. Nearly 2000 such adivasi women are shareholders in the company, and improving the livelihoods of women engaged in the collection of various forms of non-timber forest produce (NTFP), is an integral objective of this social enterprise. This effort emerges as especially crucial when one considers the numbers: every year, millions of Indians belonging to scheduled tribes collect about Rs. 200,000 crores–or 2 trillion rupees–worth NTFP from India’s forests, as of 2020.

But the communities that collect the products do not receive these returns. This happens especially in the absence of an organised approach to the NTFP markets: though collectors contribute significantly to local economies, it’s the middle men that often gain the most. Ghoomar is trying to change this. However, they must also improve their capacity to pay a high and fair price to these women.

Also read: ‘Land ownership could alter women’s roles in agriculture’

The company achieves this by taking up several value-adding and processing activities. For instance, there is demand for custard apple pulp by natural-flavoured ice-cream makers–the fruit is valued both for its taste and high nutrition. Several catering units, too, are keen to obtain this pulp for preparing shakes. So, women are trained by Ghoomar to extract the pulp from the fruit in hygienic ways. Once properly trained, they can also take up this work at various decentralised units. This pulp is then frozen at the main plant before being sold.

In addition, adivasis here also collect a number of berries. The produce is then properly selected and graded by Ghoomar, eventually making it ready for sale in a neatly packaged form. In addition, Ghoomar uses the paste from these berries to produce sweets (laddus) and a lollypop-like berry stick.

Blackberries (jamun) are not as widely available in these parts, but Ghoomar’s work extends to parts of Udaipur district, too–where these fruits can be more easily obtained. They are sliced and frozen for sale, and a delicious drink called the ‘jamun shot’ is also prepared from the fruit.

Non-edible natural products such as leaf cups and plates (dona pattas), fashioned from the leaves of the Palash tree, are among Ghoomar’s offerings. As biodegradable material, these can easily replace the plastic cups and plates that are increasingly employed for social gatherings in the region. In addition, the flowers of Palash trees are used to produce natural colours, including the gulal used in festivals like Holi.

It is these processing activities that enable Ghoomar to pay better prices to women who collect forest produce. It is, of course, a great bonus that such ventures increase opportunities for women to be gainfully employed in processing activities, over and above collecting.

Also read: One Odisha woman’s mission to preserve taste, tradition through seeds

As a result of these growing opportunities, it is common to come across several Garasia women in these villages who now have a combined annual income of around Rs. 50,000 or more from these activities–compared to an income of less than Rs. 5000 before Ghoomar’s work took root here. Dharmi Bai, for example, was able to earn Rs. 79,450 in 2024. The annual income range for many women engaged in this work is likely to be between Rs. 20,000 and Rs. 80,000.

Most of these women are married, and for many of them, collecting and processing forest produce is their only source of earning. So, they also benefit from being members of self-help groups linked to a sister organisation—Ghoomar Mahila Samiti. This provides them with access to savings and low-interest loans–on the basis of which, they can start small enterprise units on their own, also linked in helpful ways to the main company.

An effort like Ghoomar, driven forward by the work of adivasi community members, is inherently capable of harvesting forest products in ways that are more sustainable. Their knowledge of forests and tree protection equip them with an instinctive ability to know the right stage when fruits must be plucked—in order to prevent wastage and promote proper utilisation. In the process, harm to the forest is minimised, and the skills of the adivasi women can be amplified through training programmes.

This is a far cry from the approach taken by commercial agents from big cities, say locals, who tend to use discriminate methods to collect produce from the villages. In the absence of mindful techniques, this results in a shorter harvest season. The stark contrast in collection methods should prompt authorities to encourage initiatives that center adivasi wisdom at a policy level.

Also read: Bastar’s secret ingredient? The power of preservation

Ghoomar was conceptualised and planned at an early stage by a voluntary organisation called Self-Reliant Initiatives through Joint Action, or SRIJAN. At a certain stage of progress, SRIJAN handed over this effort with great potential to the community, but remained available for any technical support if required.

This model of utilising NTFP has a number of seen and unseen benefits. When only the pulp of custard apple is sold, the outer covering of the fruit remains with the community–it can be decomposed and used as manure, and the hard seeds can be spread in forests and wasteland to encourage further growth of trees. Similarly, when jamun pulp is used up, its seeds can be used separately to make medicinal products.

Similar potential is also evident in another such effort: a producer company of farmers, called Dolmashree which is at an early stage of development in the Suhagpura block of Pratapgarh district, Rajasthan. In the villages here, inhabited by Meena tribals, there are plenty of Mahua trees whose seeds are collected. But oil from this tree has to be extracted elsewhere. Once these communities are able to acquire their own processing unit, not only will they get better quality oil without having to pay others for it, the oil cake will also remain with them.

In the Pratapgarh venture, where the initial work in the community is also being supported by SRIJAN, women members of the producer company have achieved significant progress in creating orchards and vegetable gardens based on natural farming; the processing of cultivated products has great potential.

Ventures such as these, where adivasi women are shareholders, have the potential to improve, all at once, livelihoods, nutrition as well as health. It all goes back to a sustainable and smart ecological approach to our forests: processing and marketing forest produce, working produce from village trees as well as cultivating products based on natural farming methods.

{{quiz}}

Tamil Nadu-based Selvaraj is proving that farming doesn’t necessarily have to be high-tech or high-cost

Selvaraj, a 58-year-old farmer from Sesurajapuram in Tamil Nadu, cultivates crops and ideas. A decade ago, when he faced a shortage of manual labour and was unwilling to rely on expensive, corporate-made machinery, he decided to take matters into his own hands.

Unable to afford industrial equipment, he began looking at everyday items—bicycle tyres, PVC pipes, wooden blocks and metal scraps—not as junk, but as raw materials for invention. His first creation was a simple weed cutter, fashioned from a bicycle wheel and frame, with a metal blade attached to serve as the cutting edge. Selvaraj's moment of epiphany was a result of his skills in carpentry. He began designing and putting together tools suited to his needs, soil and crops.

Since then, he has gradually built a range of farming tools, all crafted from discarded materials. His innovations have made farming more efficient for himself and benefited others in the region who struggle with limited access to fuel-run machinery. Selvaraj has earned the affectionate moniker of ‘Village Scientist’ for his ingenuity and grassroots engineering. What started out as a dire necessity on his farm has now evolved into a rewarding 'side quest' in his career.

Every farmer is constantly in search of an effective way to eliminate weeds, and Selvaraj was no exception. Determined to create a solution himself, he initially used wood to build a weeding tool but soon realised it was too difficult to work with. He then turned to old bicycle wheels of various sizes and, after several iterations and experiments, successfully developed a functional design. “After cutting the frame of the bicycle, I attached small wheels and tried rolling it,” he recalls.

He has also created a dedicated WhatsApp group where farmers can seek guidance and troubleshoot issues together. In the near future, he wants to create even larger tools powered by batteries, making small-scale farming easier.

Also read: How Shree Padre built journalism for farmers, by farmers

Today, Selvaraj’s handmade toolkit includes weed cutters, hand ploughs, and a versatile 3-in-1 tool that can be used for weeding, ploughing, and harrowing. Each one of these is made using inexpensive and readily available materials, making sure it is affordable and sustainable for the rest of the farmers as well. Unlike equipment sold to the farmers by corporations that often come at a high cost, Selvaraj’s tools are priced just enough to cover labour costs and materials, keeping them accessible to the farming community. For instance, if the cost of materials and welding for a weed cutter is ₹1,500, he sells it for ₹2,000—just enough to sustain his work without hefty profit margins.

But Selvaraj’s work goes beyond just tool-making. The farmer, who grows a variety of crops on his 2.75-acre farm—from groundnut to tomatoes, carrots, beans, and millets—asserts that knowledge should be shared, not hoarded. “Ideas shouldn’t be kept secret. The farmer who learns from me will teach someone else to make the tools,” he says. He freely shares his expertise, teaching others how to build and use these tools effectively. Moreover, farmers from across the Krishnagiri district—where his village Sesurajapuram is located—and neighbouring districts seek his advice on crop quality, harvesting techniques, and ways to control pests. Whether in person or over the phone, Selvaraj is available to help fellow farmers manoeuvre the evolving challenges of modern agriculture.

Also read: From barren to thriving: The Kalpavalli success story

Despite his lack of formal education, Selvaraj is also navigating the digital landscape. While many older farmers shy away from technology, he actively shares his farming experience on Facebook, YouTube, and WhatsApp to document and impart his learnings. Through these channels, he provides real-time updates on rain patterns, soil conditions, and farming techniques so others can benefit from his knowledge.

He has also created a dedicated WhatsApp group where farmers can seek guidance and troubleshoot issues together. In the near future, he wants to create even larger tools powered by batteries, making small-scale farming easier.

Selvaraj believes that farming is about more than just producing food; it is about maintaining autonomy and resisting the growing corporate sway on our plates. He says that corporations are making it increasingly difficult for independent farmers to thrive, pushing expensive machinery and chemical-dependent agriculture. Selvaraj suggests that self-sufficiency through DIY tools and organic farming can be a solution.

However, he also acknowledges the challenges an organic farmer faces. “Whatever we do, the market decides the price. They don’t value the merit of organic vegetables. Vegetables grown without chemical fertilisers won’t be big in size,” he laments. Despite this, he wants to remain committed to sustainable farming and wishes that others do the same.

Clearly, Selvaraj’s inventive spirit extends beyond the soil and ploughs. In his free time, he crafts bamboo flutes not for profit, but for pure joy. He has taught himself how to play, losing himself in the melodies he creates and sharing them with the world. Like his tools, his flutes prove that even simple materials can be turned into something extraordinary if one wishes to.

Selvaraj’s deeds prove that farming doesn’t necessarily have to be high-tech or high-cost. One primarily has to be creative, resilient and connected to the earth.

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

{{quiz}}

Fishermen’s empty nets point to habitat destruction and ecological imbalance

Ghulam Hassan is a fisherman in the Kashmir Valley. For generations, he and his community have depended on the waters of Kashmir for their sustenance; to them, fish like the trout signify both a nourishing meal, as well as a source of income. He recalls that in the past, he could catch about 4–5 kilos of the once-commonly found fish per day. Today, however, he often rows out of the Wular lake with empty nets.

In Kashmir, an indigenous variety of trout—the snow trout—has always existed. During the British Raj, Maharaja Pratap Singh was convinced by an angler and a carpet factory owner, Frank J. Mitchel–who saw great angling potential in the Kashmiri waters–to import a batch of new trout varieties. And so, in 1899, the Duke of Bedford sent a consignment of 10,000 trout eggs to Kashmir. The consignment, however, perished on the way, and finally in 1900, a second shipment arrived from Scotland. Of these, a thousand eggs were released in the Dachigam area, while the remaining 800 were reared by Mitchel at his private facility in Baghi Dilawar Khan. Once these fry developed into fingerlings, they were introduced into various streams across the Valley.

Both rainbow and brown trout adapted successfully to the region’s waters, complementing the native snow trout populations. Recognising the potential of trout fisheries, Maharaja Pratap Singh established the first Fisheries Department in Jammu and Kashmir in 1903, appointing Mitchel as its inaugural director. Since then, trout have flourished in Kashmir’s aquatic ecosystems.

Kashmir’s trout is less spongy, more tender, and has fewer scales, making it a highly-prized fish–especially the rainbow trout, which is considered a delicacy in the region. Although not originally from Kashmir, the species thrives in this region: the area’s suitability for trout breeding stems from its cold, clear, and oxygen-rich waters, maintained at optimal temperatures between 5°C to 18°C, ideal for trout survival. The region’s pristine, glacial-fed rivers like the Lidder, Sindh, and Kishanganga provide a clean and unpolluted environment, essential for healthy fish growth.

But now, Hassan admits, “I have not seen the snow trout in two months because they are not growing as they used to. Even the common carp, which was once present in abundance, is now declining. We used to catch 4–5 kgs, even 10 kgs. But now, we get barely half-a-kilo, which has made it difficult for us fishermen.”

Also read: The rise and fall of India's Tilapia dream

So why is the fish declining? The answer lies in the rapid intervention of technology. The habitats of the trout—the streams of the regions—also happen to be a rich resource for sand mining. The high demand of this sand has led to the use of heavy machinery like JCB backhoe loaders, causing a disbalance in the delicate ecosystem. For instance, in May of 2024, more than 2500 trout died at Donkulibagh–an area in the Budgam district–because of a blockage in water supply in the process of mining of stones from a stream.

Activist Ghulam Rasool explains, “In earlier times, fishermen would catch fish in one season and extract sand in the off-season. The fisherman community, who used to do this work traditionally, understood the fish habitat, and knew where the eggs were laid. They wouldn’t disturb the habitat. Their unwritten traditional code ensured that sand was extracted sustainably, without harming the fish habitat. They understood that disturbing fish habitats would reduce their catch in the fishing season. But with mechanised sand mining, everything has changed, destroying fish habitats and disturbing the river’s natural ecological balance.”

Also read: Mumbai coastal road project leaves fishermen adrift

Kashmir houses an extremely delicate ecosystem, understood best by the communities that have inhabited the area for ages. Knowledge has trickled down, generation by generation, yet the future remains uncertain. Hassan says, “Our children are unwilling to take up this work because there is nothing left to catch. I have been fishing for 20 years, but even after throwing multiple nets, no one has caught a single fish [in the recent past]. Even after the freezing temperatures, we are here [fishing], because we have families to feed.”

Many other issues threaten the survival of this species. Illegal means to catch the fish, such as mixing bleach powder in the streams, the blatant use of pesticides and insecticides in neighbouring orchards, the construction of hydroelectric projects and dams, even rampant deforestation, all hurt the ecological and economic importance of trout.

So, what is the solution? In 2015, an idea was proposed by the then J&K Minister for Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Science and Technology, Sajad Gani Lone: install CCTV cameras on farms and broadcast a live feed on the internet, to make it easy for the government to monitor and crack down on poaching. This approach, however, ignores the larger problem of climate change and technological interventions. CCTV cameras can do little to stop JCBs: they aren’t illegal, only unethical.

Dr. Farooz Ahmed, Dean of the Fisheries Department at Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Agriculture Sciences (SKUAST), further explains, “Snow trout cannot be cultured like other fish. Instead, we have developed a breeding programme to produce seeds in controlled conditions, which we have been doing for the last five to six years. We produce seeds and small fingerlings, which are then released into lakes and rivers to replenish fish populations. For instance, if we release 1,00,000 fish into the water and 10,000 of them survive, the programme is considered successful. Through this fish ranching programme, we aim to conserve their genetic diversity.”

{{marquee}}

But such programmes, Dr. Ahmed warns, are just a temporary fix to a much larger problem. He says, “If the pollution levels keep increasing, water quality changes, and food remains scarce, this fish will die too.” During the British and Dogra rule, there were strict regulations in place to ensure the protection of trout fish, which is why they could thrive in the region. The solution is in long-term collaboration. Rasool says, “Fishermen with traditional knowledge and scientific experts must work together to develop strategies that protect fish populations and river ecosystems, and people’s livelihoods.”

As the conditions to farm trout in Kashmir only worsen, the demand seems to be on a rise. As reported in The Hindu, the Fisheries Department accounted for 534 farmers producing 650 tonnes of trout in 2019-20. In the fiscal year 2022–23, these numbers have grown to 1,143 farmers producing 1,990 tonnes of trout, marking a 200% growth. So, skyrocketing demand paired with an ecosystem unequipped to sustain it begs the question: Will the trout and those dependent on it survive this tide or will they only be left victims?

{{quiz}}

Through her tubers, pulses and millets, Sabitri Pangi is bringing diversity back to her village’s meals

In the early morning light, 43-year-old Sabitri Pangi can be found in her backyard, tending to her kitchen garden. But this patch of green is like no other. "We grow only traditional crops," explains Pangi. Among a variety of vegetables, tubers and greens, Pangi sows heirloom seeds of pumpkin, okra, and bitter gourd in the soil. "These seeds are precious gifts from our forefathers, passed down through the generations. Losing them would mean losing our identity," she reflects.

Pangi is a resident of Purulubandha, a hilltop village in the Chitrakonda block of Malkangiri district in Southern Odisha, close to the state’s border with Andhra Pradesh. The village comprises only 42 households–the majority of them belonging to the Kotia tribe–including Pangi’s.

During her childhood, Pangi worked alongside her parents on their farm in the nearby Polaspadar village, where the family practiced mixed farming and grew a variety of crops. She recalls that in those days, farmers relied solely on traditional seeds, which yielded abundant harvests. "We used to harvest crop by crop. The crops were resilient—they could withstand delayed rainfall and excessive heat. Besides, the produce was tasty and rich in nutrition," she reminisces.

.webp)

The selection and saving of seeds that come from crops with the most flavour and nutrition is a technique that has long served farmers across geographies. They also saved those seeds which had the ability to resist pests and diseases; gradually and gently, each generation of crop became stronger, tastier, more diverse. So familiar were these plants to the local regions and their climatic moods, that their seeds learnt to grow into crops that could withstand unpredictable rains and extreme temperatures.

I firmly believe that by restoring the glory of our traditional seeds, we can revive our agricultural heritage.

But by the time Pangi turned 20, she noticed a shift in farming practices. Many farmers in her village switched to mono-cropping. Hybrid varieties of paddy, maize, potato, and cotton became the dominant crops, pushing traditional varieties into the shadows. The seeds of these crops are bred to ensure uniformity and specific traits like abundant harvest each season–definitely beneficial to farmers. And initially, the yields were high, but farmers soon realised that these commercial crops struggled to survive in extreme climatic conditions.

Also read: How women in this tiny Naga village are safeguarding local seeds

Moreover, Pangi noted that farmers’ expenses were driven up year on year by the cost of these hybrid seeds as well as chemical inputs. Hybrid seeds need chemical fertilisers, because high output demands a consistent supply of nutrients, which these crops may not get from soil in a concentrated manner.

In this process, the community was losing traditional crops–and consequently, many many age-old recipes tied to them were also being forgotten. It was this farming crisis that inspired Pangi to conserve traditional seeds. "I firmly believe that by restoring the glory of our traditional seeds, we can revive our agricultural heritage," she asserts.

Today, Pangi’s two-acre farm stands as a vibrant repository of agrobiodiversity, thriving with traditional crops. She has preserved nine varieties of wild tubers, five varieties of heirloom vegetables, seven varieties of pulses, and several local varieties of paddy, millets, and oilseeds. Committed to seed conservation, she often shares and exchanges traditional seeds with farmers in her village and neighbouring communities.

Pangi cultivates several varieties of traditional tubers, including Langal Kanda (greater yam), Ful Sarenda (five leaf yam), Kasa Kanda (Indian three-leaved yam), Pita Kanda (bitter yam), Pit Kanda (cinnamon vine), and Cherang kanda (wallich's wild yam). There’s a reason why she prioritises maintaining this diversity. "These tubers are hardy crops—they grow with minimal water and resist pests. Rice may fill our stomachs, but tubers give us the strength to work longer on our farms. They provide more energy and nourishment," explains Pangi.

Also read: The tribal seed guardians of Dindori

In addition to tubers, Pangi’s farm is home to a diverse range of traditional vegetables, including Satapatri Bhendi (okra), Cheli Ludki (clove beans), Bada Kumuda (big pumpkin), Chota Kumuda (small pumpkin), and Chota Karla (bitter gourd). Pangi believes these traditional varieties surpass hybrid ones in many ways. For example, Satapatri Bhendi begins flowering after producing just seven leaves. Similarly, Chota Kumuda and Chota Karla grow faster and require less water and manure. "These varieties are well-suited to our climate and soil. They also attract fewer pests and diseases," explains Pangi.

Traditionally, the Kotia tribe has sustained itself through agriculture and selling wild produce from neighbouring forests. As farmers, the members of this tribe have always cultivated a wide variety of pulses. However, many of these local pulse varieties have become rare, surviving only with a few farmers in remote villages. So, to begin with, Pangi visited neighboring villages to collect various pulse varieties. She exchanged her own seeds with other farmers, bringing new varieties back to her farm. Today, Pangi has successfully conserved several traditional pulses, including Jailo (lima beans), Jhudunga (cowpea), Ranjh Semi (broad beans), Matia Buta Semi (brown kidney beans), Muga (green gram), Misani Biri (black gram), and Kala Kolatha (horse gram).

“These pulses are vital for the community’s health, as they have high nutritional value. They also improve soil fertility through nitrogen fixation,” explains Susanta Sekhar Choudhury, Program Manager-Seed System at Watershed Support Services and Activities Network (WASSAN), Bhubaneswar, a non-profit that works in the rainfed area for bringing prosperity and ecological security to marginalised communities.

Also read: Can nitrogen-fixing plants replace synthetic fertilisers?

Besides, the crop residues of these pulses are also used as fodder for livestock. When fodder is scarce, particularly in summer, Pangi says, “We feed crop residues to our goats and sheep. It helps maintain the health of our animals.” Pangi also grows local varieties of oil seed like Alasi (Niger), along with cereals such as Mahul Kuchi Dhana (Paddy), Kasam Jhopa Suan (Little Millet), and the Mami, Bati and Sili varieties of finger millet.

Gopinath Pangi (48), Sabitri's husband, vouches for his wife’s work with conviction. "My wife has worked tirelessly to revive our traditional seeds. It took her nearly 10 years to collect, exchange, and conserve many traditional varieties that had become rare, known to only a few farmers. Through her efforts, she has helped us reconnect with our roots."

Inspired by the diversity and vibrancy of Pangi’s farm, around 20 women from Purulubandha and nearby villages have transitioned from monocropping to multi-cropping systems using organic methods. "Initially, many women were not convinced," Pangi recalls. "So, I invited them to visit my farm. When they saw the fertile soil and healthy crops, their confidence grew. They realised that our age-old farming practices and traditional seeds can yield a good harvest."

Earlier, rice was our staple food. But after growing multiple traditional crops and vegetables, our meals have become more diverse. Now, our food plate is more colorful.

Mukta Pangi, a 37-year-old resident of Purulubandha, happily shares her experience with traditional crops. "Earlier, rice was our staple food. But after growing multiple traditional crops and vegetables, our meals have become more diverse. Now, our food plate is more colorful," she says with a smile. Similarly, Kantamal Pangi, another tribal woman in her 40s, has pledged to preserve heirloom seeds. "Growing traditional crops rejuvenates soil fertility. We use only farmyard manure, eliminating the need for expensive chemical fertilisers or hybrid seeds," she explains.

According to Choudhury, these traditional crops and mixed farming practices are deeply rooted in the ancient wisdom of tribal communities. Not only do they support local diets, but these crops also contribute to the region’s ecological balance by preserving genetic diversity and enhancing farmers' resilience to climate change.

Tribal women farmers like Pangi, Mukta, and Kantamal are relentlessly conserving local agrobiodiversity and through this, they’re also promoting traditional culinary heritage. "Crops, food, and culture are deeply interconnected in our tribal community," explains Pangi. She adds, "When a crop variety disappears, its traditional recipes vanish with it. By preserving our traditional crops, we ensure that our culinary heritage and culture continue to thrive. Our traditional recipes celebrate the unique flavours of our ancient crops."

Mukta says with pride, “Each recipe is unique as they are carefully crafted to honour our ancestral knowledge. These recipes have been passed down from one generation to the next through stories, histories, legends and myths. It connects us to our ancestors and Mother Earth.” Some of the traditional recipes of Kotia tribe include Cheli Ludki Sag (prepared from clove beans), Kumuda Je Dangarani (prepared from rice bean; the full recipe can be found at the end of this article), Kolatha Je Munika Sag (prepared from Horsegram), Ranj Semi Sag (prepared from lima bean), Bhalia Anda (prepared from custard apple), and Mandru (prepared from finger millet).

However, as the younger generations of these tribal communities are fond of urban cuisine–as part of an aspirational lifestyle– the knowledge associated with traditional food culture is eroding away. Importantly, it should also be noted that over the years, the Public Distribution System (PDS) has changed food preferences such that rice has become a staple diet in rural areas.

To safeguard the state’s tribal food heritage, the Odisha government has launched flagship programs like the Shree Anna Abhiyan (SAA), which is reviving millet cultivation and reintroducing millets to local diets across all 30 districts of the state. Additionally, the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE) is working to restore the diverse but forgotten food and culinary heritage of tribal communities in Malkangiri and Nuapada district by documentation and promotion.

"Odisha has been a pioneer in promoting agrobiodiversity," says Dr. Arabinda Kumar Padhee, Principal Secretary, DA&FE. He notes that the state has registered over 700 farmer’s varieties with the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority. Additionally, landraces from more than 500 remote villages have been mapped and documented. Amid the looming threat of climate change, it is imperative to give due recognition and agricultural policy support to these neglected crops, he underlines.

Kumuda Je Dangarani is a traditional recipe of the Kotia tribe, one of many.

To cook this delicacy, first wash the rice beans thoroughly with water. Once washed, soak the rice beans for at least two hours.

After two hours, boil the beans with a pinch of salt for 15-20 minutes on a medium flame.

Cut your pumpkin into cubes. Add this pumpkin and turmeric powder to the rice bean and cook for another 15-20 minutes. Add chili powder to the cooked rice bean and pumpkin. Add salt and garlic into the mix. Cook until the gravy thickens. Serve hot with rice or roti.

{{quiz}}

Please try another keyword to match the results