Rama Ranee

|

February 23, 2026

|

12

min read

Raised by nature: Bonds with farms, forests help children grow holistically

Safe spaces, outlets for creativity and curiosity, and a connection to the Earth—nature can mean many things to kids

Read More

Challenges of production and shipping, coupled with cattle health, pose threats to the artisanal cheese segment

Clad in a white apron and hairnet, Benny Ernst, manager of La Ferme Cheese in Auroville, Pondicherry, is inside the processing room of his fromagerie, draining the freshly made curd with the help of his team. He has been here for the last 24 years making artisanal cheese and supplying the residents of the Union Territory. His small set-up makes Cheddar, Gruyere, Parmesan, and some other hard cheeses throughout the year. While in his two-and-a-half decades in India, he has observed a growing fondness for cheese, climate change is making it harder for him to keep up with the demand.

According to an analysis by IMARC Group — a global management consulting firm — the size of the cheese market (both processed and artisanal) in India reached ₹107.54 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach ₹593.47 billion by 2033, exhibiting a growth rate (CAGR) of 19.86% from 2025 to 2033.

According to Team Dairy Experts, a Pune-based organisation that provides consultations for dairy management, India’s cheese production (both processed and artisanal), which stood at 10,000 metric tonnes (mt) in 2010, rose to 70,000 mt in 2023. This has been attributed to several factors, like increased disposable income, e-commerce, and increased preference for international cuisines.

Also read: How artisanal cheese is saving traditional herders

The last two decades have seen a sudden rise in fromageries in India, from Uttarakhand’s Darima Farms in Mukteshwar, Uttarakhand to Acres Wild in Coonoor, Tamil Nadu.

But climate change is already challenging this fledgling industry. As temperatures rise, everything from the availability of cow feed to the quality of milk, the maturation of cheese, and its shipping is affected.

Over the last few years, Ernst has seen a spike in his electricity bills. His cold room, where the cheese matures year-round, is air-conditioned to mimic the climatic conditions of European cheese caves, where the natural temperature is below -10°C to -12°C. This allows for the maturing of cheese without the need for artificial cooling.

But Ernst has observed that power consumption for cooling has increased in the last few years as global temperatures soar.

“The cold room needs a temperature below -8°C, which is impossible without air conditioning in India. So, it is a given that as the outside temperature increases, more and more electricity will be needed to maintain this temperature, which might affect the prices, too. So far, we have not raised the prices, but if the bills keep going up, we will have no option in order to stay in business,” Ernst says.

This particular summer of 2024 was terrible. We experienced a hike of around 30% in our electricity bills for the production and cold storage.

Brothers Prateeksh and Agnay Mehra, founders of The Spotted Cow Fromagerie in Mumbai, established in 2015, have also found that their power consumption in the summer of 2024 was at an all-time high. “This particular summer of 2024 was terrible. We experienced a hike of around 30% in our electricity bills for the production and cold storage,” Prateeksh says. He adds that the entire milk supply chain was affected in the summers, leading to higher production costs.

The maturation of cheese has always been a challenge familiar to cheesemakers, but rising temperatures are now exacerbating other issues in India’s dairy industry. A shortage of fodder for milch cattle, difficulties in transporting milk from dairy farms, and challenges in shipping the finished product are becoming significant threats—challenges that are only expected to intensify if global temperatures continue to rise.

From January to September 2024, the global mean surface air temperature was 1.54°C above the pre-industrial average, surpassing the 1.5°C threshold set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This increase has already profoundly impacted the dairy industry, leading to food shortages, higher prices, and losses for the livestock-agriculture sector worldwide, Dr Abhinav Gaurav, Advisor for Livestock Management at the Environmental Defence Fund, told Good Food Movement. For India’s cheesemakers, these changing conditions pose fresh obstacles in an already delicate process.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Dairy Research titled “Economic losses in dairy farms due to heat stress in sub-tropics: evidence from North Indian Plains” states, “Heat stress in dairy animals entails significant economic costs for regions located in either temperate or tropical climatic zones. The losses arise from a decline in milk yield, reduced reproductive rates, and worsening of milk composition, which results in a significant financial burden to the dairy industry.”

According to estimates in a research report in The Lancet, the milk production losses in India will be up to 25% by 2085. According to another study conducted by the Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute (IGFRI), projected milk production losses because of heat stress in the northern plains of India will be around 629 thousand tonnes by 2039 and in economic terms, these losses would be around ₹2,100 crore annually.

“We are not a very large setup, but in the summers, even we have to either scale down production or buy more milk, so we lose money. So far, we have managed to get by without a price rise, but if the temperatures keep rising, we will increase our prices as we also have to pay the farmers and pay salaries to the staff to keep up the production,” Ernst explains.

Also read: Heatwaves cast shadow on India's food future

In the dairy industry, the Temperature Heat Index (THI) (a composite value) indicates the level of thermal comfort or thermal stress in dairy cattle. As the atmospheric temperature and humidity rise, the THI value increases, and the animal starts experiencing heat stress, which is manifested through various physiological expressions.

One of the indicators or physiological manifestations of dairy cattle experiencing heat stress is the animal going off feed, reduced milk production and altered milk composition. The lactating animals (cattle) and buffaloes experience more heat stress than the rest. During extreme summer and early monsoon months, it results in heat stress-induced production losses.

The THI value from July to September 2024 throughout the day (and night) remained above the ideal 72, where animals remain in thermal comfort. Beyond THI 72, they start experiencing thermal stress, resulting in loss of milk production and compromised health and well-being.

“One of the indicators or physiological manifestations of dairy cattle experiencing heat stress is the animal going off feed, reduced milk production and altered milk composition. The lactating animals (cattle) and buffaloes experience more heat stress than the rest. During extreme summer and early monsoon months, it results in heat stress-induced production losses,” Gaurav says.

Ernst and Prateeksh Mehra further highlight the problem of fodder shortage in summer, which leads to a spike in prices. This means shelling out higher sums of money to procure milk and an added production cost.

When there is a shortage of fodder and grass, the prices go up, and if the farmers substitute it by increasing the quantity of dry grass, the quality of the milk deteriorates. In the last few years, fodder prices have increased to over ₹2,500 per quintal in various states like Maharashtra, as fodder production has also suffered due to climate change.

Gaurav adds that raised temperatures and increased humidity decrease milk production by 20-30%, with losses being more pronounced in small-holder farming systems and buffalo farms—both of which form the milk supply backbone of the artisanal cheese industry in India.

{{quiz}}

“The associated effects of heat stress is on the physicochemical properties and composition of raw milk which includes decrease in milk protein, lower casein content, lower level of fat and changes in the fatty acid profile. This altered milk composition, especially the lower milk protein and fat percentage, has a pronounced impact on the quality and taste of artisanal cheese,” he says.

Mehra corroborates the claim. “To keep up our production, we had to buy more milk to produce the same quantity of cheese. While it was an added expense at our end, as we could not increase the prices of cheese for just one season in 2024 as we are on a rate contract,” he says.

Chris Zandee, owner of the company Himalayan Products based in Kashmir, which makes a type of artisanal cheese, points to the irony of the growth of the artisanal cheese industry in India. “India is not naturally a cheese-producing country as cheese is not a tropical food; manufacturing cheese with the help of cold-rooms and these cold-supply chains and shipping it for long distances leads to a higher carbon footprint. It is kind of hypocritical,” he says with a laugh.

Zandee adds that while his cheese cave is air-conditioned, the AC is only used in emergencies as the 2-foot-thick walls naturally maintain the temperature around 15°C.

“I make Indian cheeses like kalari and some European ones like gruyere, gouda, cheddar, feta and mozzarella, and ship Pan-India. Most of these are salted so that they have a longer shelf life. Soft French cheeses need a far lower temperature and special dedicated rooms, and they do not ship well, so we do not make those,” Zandee says.

Indian cheese-makers also face the challenge of shipping cheese. To ensure a Pan-India supply, they have to ship the cheese in insulated boxes with packs of dry ice to prevent spoilage. Rising temperatures will make shipping cheese harder, requiring better cooling and faster deliveries.“The thermal boxes we use maintain cooling for up to 48 hours, but if there are further delays, it does get affected. So, if temperatures rise, we will need more effective packaging methods that make cooling last longer. Besides, I am forced to point out that shipping cheese via air or road also adds to the emissions,” Zandee explains.

While this budding industry in India is already suffering, traditional cheese producing countries like Italy, France and Switzerland are also facing the brunt of global warming. Cheesemakers are demanding relaxation of rules for their cheeses to qualify under the Appellation d’Origine Protégée or AOP—or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO)—standards, which are standards of quality to ensure the best possible cheeses get the certification. The certificates of these standards are granted to just 46 out of 100 cheeses in France as the rules are very hard to follow, and climate change is making it even harder for cheesemakers to adhere to the traditional methods.

Also read: How chocolate makers are coping with a cocoa crunch

“The production of cheese and its quality will definitely be affected if temperatures keep rising like this. So, yes, it is a big possibility that many small set-ups may go out of business and the bigger ones increase the prices. The future of artisanal cheese in India is uncertain,” Ernst says.

Through this approach, value can be found in surplus food and by-products

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

India – one of the world’s largest food producers – loses an estimated 40 percent of its produce annually. This colossal waste not only squanders natural, technological, and human resources, but also costs the economy an estimated Rs 926.51 billion every year, adding to its existing strain. Unlike in developed countries, where the majority of food waste comes from consumers’ homes and supermarkets, food waste (or more accurately, food loss) in India primarily occurs before food reaches retailers or consumers. This is largely due to inefficiencies in post-harvest storage, transportation, and distribution. A lack of proper cold chain infrastructure leads to spoilage, especially for perishable items like fruits, vegetables, dairy, and meat. Inadequate warehousing and poor handling practices result in grain losses, and market oversupply causes vendors to discard large quantities of food.

Addressing these inefficiencies should be the first priority, as investments in better storage, transportation, and market linkages can significantly reduce food loss at the source. However, even with improved infrastructure, some agricultural and food materials will inevitably end up as waste due to factors such as logistical challenges imposed by the country’s geography and a changing and increasingly unpredictable climate. The circular bio-economy movement, which emphasises reducing waste and repurposing resources into valuable products, offers a transformative pathway to turn these “inevitable” losses into economic and environmental gains.

The circular bio-economy builds on the principles of a circular economy, which aims to minimise waste by sharing, reusing, repairing, and recycling materials for as long as possible; ensuring that only what is truly unusable is discarded. The concept was born in the 1970s and 80s, out of the necessity to change the unsustainable consumption patterns of the traditional ‘take-make-dispose’ model, also known as the ‘linear economy’.

Creating a circular bio-economy involves applying this principle in the context of biological resources such as agricultural surpluses, wastewater, and forestry by-products. However, given the perishable nature of these resources, it is not possible to recycle them in the same way that one would materials like metals, glass, and electronic waste. While these materials can be recycled multiple times, creating a nearly perfect loop, biological materials are typically repurposed across different applications through creative and innovative processes before they eventually break down and return to the environment.

In recent years, the circular bioeconomy movement has gained momentum worldwide as governments and industries seek sustainable alternatives to resource-intensive production models. The agrifood industry is an important focus, but there is also a growing interest in circularity principles from other sectors of the bio-economy. The textile industry, for instance, consumes vast amounts of water and synthetic chemicals, but circularity-inspired innovation such as developing bio-based fibres from agricultural residues, scaling up textile recycling, and using biodegradable dyes can reduce waste and environmental impact. Similarly, the biofuel and bioenergy sector, often seen as a greener alternative to fossil fuels, still relies on resource-intensive monocultures and has large land-use footprints. However, by embracing circularity principles, this sector can shift towards advanced biofuels derived from agricultural waste, algae, and organic by-products, reducing competition with food production while improving overall sustainability.

The European Union has placed the bioeconomy at the core of its sustainability policies, investing in bio-based industries, regenerative agriculture, and waste-to-energy solutions while emerging economies in Latin America and Africa are leveraging circular strategies to tackle post-harvest losses, food insecurity, and rural development challenges. Across Asia, governments and businesses are also adopting this model to address food and agricultural waste. In South Korea, for example, the government has successfully mandated food waste recycling, diverting over 95% of food waste from landfills by converting it into livestock feed, compost, and bioenergy. Meanwhile, China is converting agricultural waste into biofuels, strengthening recycling systems, and investing in circular innovations to reduce waste and maximise resource efficiency.

Also read: Is a world without farmers possible?

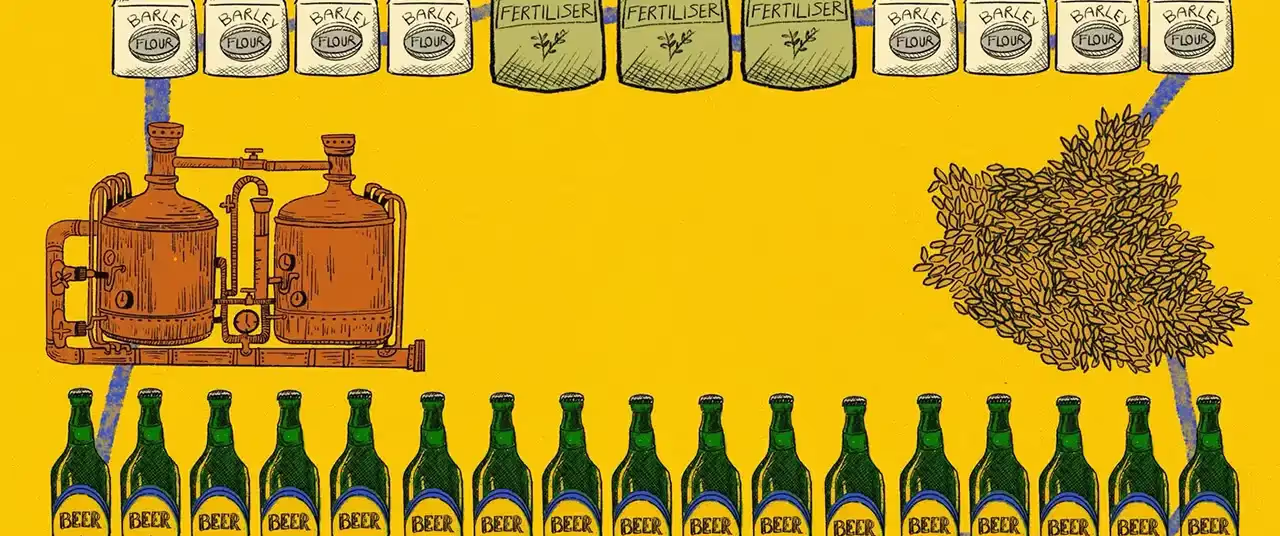

When the circular bio-economy philosophy is applied to food systems, surplus food and by-products are turned into valuable resources, making the best possible use of the nutritional and biochemical properties of food. This is popularly referred to as ‘upcycling’ and can be done in several ways. For example, spent grains from breweries, which would otherwise go to waste, can be repurposed into nutritious flour for baking bread, biscuits, and other baked goods. Similarly, fish processing by-products, such as bones and trimmings, can be converted into fishmeal and fish oil for animal feed and aquaculture, or repurposed into bioactive compounds used in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

Another example is integrated farming systems, where livestock like chickens are raised not only for eggs and meat but also to help manage food scraps, acting as natural waste processors. Their manure, in turn, serves as organic fertiliser, enriching soil health and reducing the need for synthetic alternatives. Also, mushroom cultivation presents a valuable opportunity in the circular bioeconomy, as mushrooms can be grown on agricultural by-products such as coffee grounds, spent grains, or fruit and vegetable pulp, transforming what would be waste into a nutritious food source. Once the mushrooms have been harvested, the remaining substrate can be used as compost to enrich soil.

Beyond food production, organic waste that can no longer be repurposed for consumption can still generate value through biogas production, converting food scraps into renewable energy while producing digestate, a nutrient-rich by-product that can be used as fertiliser. Similarly, surplus food and agricultural residues can be processed into biomaterials for sustainable packaging or edible coatings, replacing plastic and reducing reliance on fossil fuel-based materials.

Also read: How ancient recipes are reclaiming India’s plate

Frugal innovation lies at the core of the circular economy, and India has long embraced this philosophy across industries and everyday life. Although many traditional agricultural and culinary practices align with circular principles, scaling up circular initiatives is riddled with systemic barriers.

One of the biggest obstacles is the lack of financial and infrastructural support for circular innovations. While large-scale agribusinesses benefit from subsidies and existing infrastructure, small and medium-sized enterprises and farmers working on circular initiatives struggle with high upfront costs and limited access to credit. Government policies still favour linear production models, with subsidies promoting water-intensive crops, chemical fertilisers, and large-scale monoculture farming, rather than supporting regenerative or circular approaches. Redirecting these subsidies towards sustainable agriculture, waste-to-value initiatives, and decentralised food processing could accelerate the transition.

Beyond financial barriers, circular farming remains difficult to scale due to weak knowledge-sharing networks and limited technical support. Many farmers engaged in circular agriculture are driven by a strong pro-environmental mindset. However, they often lack access to structured training or best practices, forcing them to rely on trial and error to implement circular methods. Circular farming is not unknown to farmers; they even admit that the information is “simple and easily available,” but concentrated in the hands of a few organisations that want to profit off of making it seem difficult. From Rajasthan to Madhya Pradesh, farmers are learning by doing. Unlike conventional farming, where techniques are passed down through generations, circular farming lacks a robust support system. Strengthening peer-learning networks, training programmes, and extension services could provide much-needed guidance for farmers and small-scale entrepreneurs looking to transition.

Another challenge is weak market linkages, meaning that food producers and buyers are not well connected to each other. This issue is compounded by supply chain inefficiencies such as delays and poor coordination in transferring produce, side-streams, and surpluses between different stages of production; further preventing circular food systems from scaling. Many farmers and small enterprises producing organic, low-waste, or upcycled food products lack access to stable markets or distribution networks, making it difficult to compete with cheaper, industrially produced alternatives.

In many Indian households, wasting less is an ingrained domestic habit. However, applying these principles at scale is not straightforward or cheap.

Strengthening farm-to-market linkages, investing in cold storage and transport infrastructure, and creating financial incentives for sustainable food businesses would help address this gap. The central government can play a role in this by redirecting subsidies toward sustainable food production and expanding financial support for circular initiatives. However, state governments are equally critical in implementing region-specific policies and infrastructure projects. Additionally, social enterprises, farmer cooperatives, and local food collectives can step in to create alternative distribution networks, offering market access to small producers and upcycled food ventures. Public-private partnerships could also facilitate investment in storage and logistics, ensuring that perishable food items reach the market with minimal losses.

Also read: Sowing trust through community-supported agriculture

In addition to these efforts, another major bottleneck must be overcome – the lack of a strategic regulatory or policy framework. Unlike in countries such as the Netherlands and China, where circular economy principles are embedded in national policies, India lacks clear guidelines, incentives, and enforcement mechanisms to promote sustainable food production and processing. Establishing goals at the national and state levels for using resources more efficiently, implementing environmental laws focused on improved waste management, and incentivising the purchase of sustainably made products could provide the necessary structure for businesses and farmers to adopt circular practices more widely.

Repurposing waste and by-products should become the norm rather than an added-value feature. Ideally, circular food production should not come at a higher cost, as in principle, using waste streams should be more cost-effective than relying on virgin raw materials.

Finally, limited consumer awareness and demand remain barriers to the adoption of products produced by applying circularity principles. In many Indian households, wasting less is an ingrained domestic habit. However, applying these principles at scale is not straightforward or cheap. Farmers and food producers must go against established supply chains, invest in alternative processing, and bear additional costs. As a result, products made using circular principles often come at a higher price due to the added costs of alternative processing, labour, and supply chain adjustments. However, consumers may not perceive the added value. Some may assume that food producers already minimise waste as a standard practice, while others may question why they should pay a premium for what is essentially ‘leftover’ or repurposed material. Unlike other, better-established sustainable foods such as organic, circular food lacks a clear consumer narrative, making it harder to justify its higher price point. Without strong messaging, eco-labelling, and consumer awareness campaigns, these products struggle to gain traction.

However, while consumer-focused measures in this regard would be a step in the right direction, the long-term goal should be for circularity to become an inherent part of the food system. Repurposing waste and by-products should become the norm rather than an added-value feature. Ideally, circular food production should not come at a higher cost, as in principle, using waste streams should be more cost-effective than relying on virgin raw materials. However, achieving this will require systemic changes, including better-designed supply chains, incentives for waste-to-value innovations, and policy support to level the playing field between circular and conventional production. Once these structural barriers are addressed, circular practices can be integrated seamlessly into food production, reducing costs and making sustainability the default rather than an exception.

{{quiz}}

At Adike Patrike, farmers turn their experiences into valuable lessons for others

When it comes to their successful careers, farmers Marike Sadashiva and ‘Jack’ Anil vouch for an unusual source: the monthly magazine Adike Patrike.

Sadashiva converted 25 acres of his arid land into a water-surplus property when he implemented the water conservation techniques he learnt from the farm magazine in the early 1990s. Today, he owns a 10-acre organic farm and a 15-acre natural forest in Puttur, located in Karnataka’s Dakshina Kannada district.

“I couldn’t have become a successful farmer without Adike Patrike,” Sadashiva confesses. “The articles on water conservation inspired me to dig rain pits and harvest rainwater, and the results were extraordinary. Water scarcity on my land is now a thing of the past.”

Anil, on the other hand, earned a global reputation as an expert in budding jackfruit plants from leaves after Adike Patrike featured his innovative technique 20 years ago. Farmers from across the region flocked to his nursery in Puttur to graft and cultivate rare jackfruit varieties. His expertise also drew the attention of several Indian universities, which sought his guidance to promote this unique method.

In fact, working with jackfruits became so synonymous with Anil that people began to call him Jack. “I embraced the nickname with pride,” he says, reflecting on his journey.

Tens of thousands of such farmers in Karnataka have reaped countless benefits from Adike Patrike, a publication dedicated to agriculture that has been the source of diverse, insightful stories for the past 36 years.

At the helm of its editorial operations throughout this journey is 68-year-old Shree Padre, who describes himself with pride as a “farmer by profession and journalist by obsession.”

Innovation has been Padre’s hallmark. Farming and agriculture are extremely scientific, expansive subjects, and yet, he did not fill the magazine’s pages with dense research papers. Padre chose another, unique approach: he mentored farmers to become writers themselves. These farmer-journalists share their personal experiences, turning their practical knowledge into compelling stories. Today, Adike Patrike boasts a robust network of farmer-writers across Karnataka, who work the fields during the day and document their insights for the community by night.

.avif)

“That’s how we’ve lived up to our reputation as a magazine ‘for the farmers, by the farmers, and of the farmers,” Padre explains. “When farmers share their experiences, the world listens, and that’s what makes Adike Patrike truly unique.”

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

Padre’s transformative interventions in this space began long before he took charge of Adike Patrike. Among other movements in the years leading up to his editorial role, he was instrumental in exposing the devastating impact of endosulfan, a highly potent neurotoxin used as a pesticide, on humans and animals in his village of Padre and the surrounding regions of Kerala and Karnataka.

Between 1975 and 2000, the public-sector Plantation Corporation of Kerala (PCK) had aerially sprayed endosulfan over 12,000 acres of cashew plantations in Kerala. The toxic residues of this pesticide spread widely through villages in the neighbouring state of Karnataka. It spread through the air, contaminating soil, water, and at large, the environment.

No one knew that the aerially sprayed pesticide was endosulfan. I was the first to confirm it from an official of the plantation corporation, whom I befriended. The government had kept it a secret until then.

The results were catastrophic: countless lives were lost, and innumerable cattle, frogs, fish, and microorganisms perished. Thousands of children went on to be born with severe congenital disabilities–including hydrocephalus, neurological disorders, epilepsy, cerebral palsy–as well as profound physical and mental impairments.

Initially, the residents were at a loss. They had no idea what brought upon this sudden and devastating suffering. “No one knew that the aerially sprayed pesticide was endosulfan. I was the first to confirm it from an official of the plantation corporation, whom I befriended. The government had kept it a secret until then,” Padre says.

The revelation sparked massive protests across Kerala and Karnataka. However, the issue failed to receive the widespread attention it deserved—until Padre intervened. He penned a detailed report, accompanied by striking photographs, and submitted it to the editor of the now-defunct The Evidence Weekly. The resulting story, sharply titled, ‘Life is cheaper than cashew,’ finally caught the eye of national and international media–but not just this: the story also brought the matter to the attention of policymakers.

Padre was working on the ground; among other things, he accompanied visiting journalists on their ground reporting trips to the affected villages. But despite these efforts, it took years before the government finally banned endosulfan. Tragically, even today, thousands of victims of this chemical’s brutal attack continue their long and arduous struggle for financial aid, rehabilitation, and access to adequate healthcare facilities.

The endosulfan interventions marked a turning point in Padre’s life.

While pursuing his undergraduate studies in Botany, Zoology, and Chemistry at St. Philomena College, Puttur, the young Sree Krishna (as he was then known) regularly displayed his cartoons on the college notice board under the pen name “Shree Padre.” His talent caught the attention of prominent publications, including Shankar’s Weekly, which featured his work.

.webp)

However, Padre considers his interview with three stalwarts of Indian cartooning–Abu Abraham, R.K. Laxman, and Mario Miranda–during an event in Bangalore as a milestone in his early career. The interview was published in 1980 in Mathrubhumi, a renowned Malayalam literary magazine edited by the late Jnanpith awardee M. T. Vasudevan Nair. “I sent the English text to Mathrubhumi, and to my surprise, they published it in three installments,” Padre recalls, holding a carefully preserved copy of the magazine.

But as he worked with the victims of the endosulfan crisis as well as journalists covering the issue on the ground, Padre’s focus shifted from cartooning to writing.

Also read: How an Alappuzha coir exporter nurtured a one-acre forest

In the 1980s, areca farmers in southern Karnataka had a crisis on their hands: areca–the betel nut–prices had tanked, and farmers’ income had consequently plummeted. This is when the Mangalore-based All India Areca Growers’ Association intervened, and decided to co-opt professionals who could help study the problem and offer solutions for the farmers. They also proposed launching a publication to educate and unite areca growers in Dakshina Kannada.

.avif)

For this initiative, they turned to Padre, an areca farmer himself, to lead the effort. And thus was born Areca News, an occasional newsletter. “It happened quite accidentally,” Padre admits. “The association’s office-bearers requested me to take charge, and I couldn’t refuse.”

Eight years later, the publication transitioned to the Farmer First Trust, which launched Adike Patrike as a monthly magazine, headquartered in Puttur.

Today, if you walk into the magazine’s office, you are enveloped by its old-world charm: the antiquated tables, chairs, fans, and a fading red oxide floor take you back in time. This is where the editorial team gathers, to discuss new stories and content for its readers. When the editorial process gains momentum in the second week of every month, Padre finds his schedule getting tighter: he begins his day early, instructing workers on his farmland about manuring and produce procurement, before embarking on a 25-kilometer drive to the magazine office. Once there, he collaborates with colleagues on story ideas, identifies farmer contributors, and delegates tasks to ensure all articles are filed on time.

The magazine is printed by Codeword Process and Printers in Mangalore, 50 kilometres west of Puttur, in the fourth week of every month. Subscribers receive the finished magazine by post in the first week of the following month. “Strict adherence to the schedule has ensured that Adike Patrike has never missed an edition in 35 years, except during the COVID-19 pandemic. We distributed e-magazines to compensate for the miss,” Padre says.

Also read: How the 'makrei' sticky rice fosters love, labour in Manipur

A hallmark of Adike Patrike is its consistent campaigns aimed at promoting underutilised fruits and value-added farm products.

One standout example is the ongoing effort to popularise jackfruit, a fruit that grows abundantly in southern India, but often goes to waste–thanks to a lack of awareness and preservation facilities. Since 2016, the magazine has published 36 cover stories on jackfruit, exploring topics like cultivation, processing, value addition, and preservation of the fruit. These stories emphasise the fruit’s nutritional richness — its high levels of Vitamins B-Complex and C, along with essential minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and iron — as well as its environmental benefits, including its ability to cool microclimates and grow without fertilisers.

{{marquee}}

Other impactful and delightful campaigns include Ba-Ka-Hu (Bale Kai Hudi), that promoted banana powder, fabric dyeing with areca nut syrup, river rejuvenation, and chemical-free vegetable cultivation. These campaigns have helped farmers understand critical issues that need their attention, and inspired them to adopt sustainable practices in their work.

Over the years, Adike Patrike has evolved into an inclusive publication that caters firstmost to its patrons: farmers. “Our focus isn’t just on adike (arecanut); it’s on farmers as a whole. We publish stories on anything and everything that broadens their horizons,” Padre says.

{{quiz}}

(Photo Credits: Sandeep S, Sreejith M, and TA Ameerudheen)

Avian flu symptoms in humans can resemble those of regular flu, making it difficult to diagnose without testing

The terms “bird flu,” “HPAI,” or “H5N1” have been reappearing in the headlines. These words are often used interchangeably to refer to the viral disease known as avian flu, that primarily affects birds. H5N1 is a specific strain of this virus that has been linked to recent outbreaks. Meanwhile, HPAI, or “highly pathogenic avian influenza,” refers to a classification of deadly strains–this group indicates the virus’ potential to spread rapidly and cause significant illness or death in birds. In fact, birds affected by this strain are left with a mortality rate of 90-100%.

Infected birds shed the avian virus through their saliva, mucus, and fecal matter. Other animals can carry the virus in their respiratory secretions, blood, organs, or even milk. Birds may contract the flu if they come into direct contact with infected birds, their fecal matter or even virus-contaminated water or soil. But it’s not just birds–this virus can occasionally also spread to other species, including mammals like cats, cattle and, in rare cases, humans. Though this transmission is rare, close contact to the HPAI strains has caused the virus to jump to cats, for instance. Mammals like cats and even humans can contract bird flu by either being in direct contact with infected birds, or consuming them.

As of early 2025, H5N1 cases have been reported in nine states across India, prompting the central government to take measures to improve the current surveillance and biosecurity measures at poultry farms.

Also read: How our meat industry is feeding antibiotic resistance

Given the potential risks associated with bird flu, precautionary measures are necessary to limit the potential spread of the disease. Here’s what you can do:

While the human influenza vaccine does not protect against bird flu, it can help healthcare workers focus on cases that need immediate attention. Because both types of flu present similar symptoms, being vaccinated against the human influenza helps your healthcare provider eliminate it, and avoid diagnostic confusion.

Dogs and cats are not common carriers, but they can contract bird flu in rare cases. Keep them away from sick or dead birds.

Animals with the flu may show signs of heavy breathing, rapid respiration, or redness in their eyes. In more severe cases, they might exhibit lethargy, loss of appetite, difficulty maintaining balance, or swelling around their faces. Other symptoms can include nasal discharge and diarrhea.

Treatment approaches differ depending on the species, and while some animals can recover with appropriate care, the infection can be fatal. Prevention is the effective way to reduce the risk involved.

An oldie but a very effective goodie: wash hands frequently, especially after handling birds or visiting farms.

Bird flu symptoms in humans can resemble those of regular flu, making it difficult to diagnose without testing. Common symptoms include:

It is important to note that infection in people cannot be diagnosed by clinical signs and symptoms alone; laboratory testing is needed. Diagnosis requires a lab test using nasal or throat swabs. It should be noted that testing is more accurate when the swab is collected during the first few days of illness. Currently, facilities to test humans are available at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi and the National Institute of Virology in Pune.

As of publishing, there is no evidence of human-to-human transmission of H5N1. Most cases in humans have resulted from direct contact with infected poultry or contaminated surfaces.

Foods, goals, activity: a simple formula for a protein-rich diet

Protein is the talk of the town. A simple log in to your social media is all it takes to be introduced to a myriad of protein-forward fitness content—from discussions on which supplement is the best for you, to quick recipes that pack at least 20g of this nutrient. College canteens are keen on serving protein bars to their students, and you’re sure to find a protein-packed alternative to your favourite treat at the grocery store. The message is clear: you can’t ignore protein if you wish to be healthy.

Most Indian nutritionists agree that India’s staple diet is primarily plant-based and protein-deficient. A recent study discovered that over two-thirds of Indian households are consuming less protein than required. Health enthusiasts, gym buffs, and athletes are encouraged to rack up at least 100 g of protein per day to improve their physique, but the body also appreciates moderation. Individuals with medical conditions need to be even more careful with their intake. Consuming more protein than you can handle has its repercussions.

Hence, it's essential to understand the intricacies of this powerful nutrient. How much protein should you really be having?

Protein is considered an all-stop nutrition god for primarily three reasons: it builds and repairs muscles, boosts overall health, and is usually effective when paired with the goal of losing weight. The human body has more than 20,000 proteins-coding genes, and each protein serves a distinctive purpose. Essential components like enzymes, haemoglobins, hormones, muscles, and keratin that constitute our skin and hair are made up of protein.

Protein manages the wear and tear in our body. When we exercise, there are microtears in our muscles, which the protein fixes. It builds muscles.

When we consume protein, it is broken down into amino acids at the time of digestion, which act as the building blocks of the body. Dr Krutuja Hukeri, a sports and clinical nutritionist based in Mumbai, elaborates, “Protein manages the wear and tear in our body. When we exercise, there are microtears in our muscles, which the protein fixes. It builds muscles."

Also read: Meal prep: How Indian kitchens can optimise time, taste

Protein is also considered a wonder for weight loss. It increases metabolism and keeps one satiated for longer. Protein is also responsible for regulation of hormones, a few of which happen to be weight-regulating. It reduces your hunger and thus, can decrease calorie intake. Dr Hukeri further brings forth the nutrient’s significant contribution in maintaining and improving the body’s immunity. Antibodies are made up of protein and help fight off viruses and bacteria.

Dr Deepika Vasudevan, the founder of Bengaluru-based Nutrifuel, even asserts that growing children and adults require 1.2 g per kg of their body weight, per day, to help with key developments in the body. However, the specific amount that every person requires differs based majorly on our activity levels.

According to the Mayo Clinic, protein should make up 10-35% of our daily calorie intake. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) recommends that individuals should consume 0.83 g per kg of their body weight, every day. Keeping in line with this, nutritionists recommend that sedentary individuals consume about 0.8 g per kg of their body weight. Whereas an active individual is recommended to consume between 1 to 1.2 g per kg of their body weight. This is a roughly calculated figure; it is, of course, best recommended to consult a dietitian.

Furthermore, it is important to take into account any preexisting medical conditions. Dr Vasudevan adds, “For instance, if someone has a kidney infection, we advise them to consume the bare minimum quantity of protein, which would be around 20 g. If they are on dialysis, they can consume more; otherwise, the kidney will not be able to metabolise the protein.”

Clearly, protein is necessary: aside from low immunity and weak muscles, not meeting your protein requirements can lead to inflammation of the digestive tract and cause your metabolism to slow down. But overdoing it also has its downsides. Long-term overconsumption of protein is noted to have caused intestinal discomfort, dehydration, and liver and kidney injuries, to name a few. Exponentially increasing protein intake is known to cause bloating and increased body heat levels. The key here is to regulate your intake and not ingest any more than 2g per kg of your body weight in a day.

Doctors explain that excessive consumption of protein, specifically animal protein, increases the level of cholesterol and saturated fat in our body. This increase in turn predisposes us to heart disease, kidney damage, and atherosclerosis, which is a build-up of fats and other substances in the arteries, affecting blood circulation. Others have shed light on an increase in gut dysbiosis: an imbalance in our gut health, which affects nutrient absorption and then puts our health at risk.

Dr Hukeri is of the opinion that it is not protein that is the problem, but merely our approach. She explains, “It is important to consult a dietitian. People must make note of simple things such as drinking more water so that protein can be broken down easily by the body and then utilised. The intake must also be increased gradually and slowly so that the body can adapt to it.”

Secondly, one must remember that their protein intake should be proportional to their activity. Excess protein is stored in the body as fat—if individuals are pairing their increased protein intake with the goal to lose weight and gain muscle, they might not be satisfied with the results if their intake does not match the intensity of exercise.

Also read: How the world's top chess players fuel their minds

Protein powders have been a top accessory for health enthusiasts for a long time now. They act as a dietary supplement, where the protein is derived from sources like hemp, soy, or whey. With the industry booming post-pandemic, more and more people turn to supplements to fulfil their daily requirements. But, with a surge in consumption comes a surge in complications. In fact, people have often complained of symptoms like diarrhoea, bloating, and gas upon consumption.

The problem is multi-faceted: on one hand, nutritionists fear that individuals have turned to powders that are adulterated. In a recent study by California-based NGO Clean Label Project, dedicated to cultivating transparency in food and consumer product labelling, they discovered that 83% of the powders in the US market contained unusually high amounts of heavy metals like lead and cadmium. These metals are attained in the manufacturing process. In India, it becomes a trickier subject because supplements are not governed by regulations for drug manufacturing – they are considered as “food for special dietary use”, and fall under the ambit of the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI).

Overconsumption proves to be the other challenge. The sheer amount of excess protein strains the kidneys, which have to excrete the nitrogen as urea—increasing the risk of kidney stones and allergies. Soy-based protein is also known to alter hormonal levels. Furthermore, supplements can alter gut health, changing the microbes. This explains the irritability in the stomach. While consuming more protein than required has always been harmful, the act of overconsumption becomes more common when protein is available to consumers in a concentrated form like supplements, rather than in whole foods.

It is absolutely possible to attain the recommended amount of protein from a well-balanced diet. It is only when someone is an adult with a limited diet, suffers from a medical ailment, or is involved in endurance sports that they are advised to take up supplements. The best route is to check for ingredients of the supplement and their digestibility, allergens, and quality. Explore third-party testing and certifications and turn to a certified professional.

Also read: Micronutrients 101: Your guide to nature's tiny health boosters

Despite food-led protein options being available to individuals, they fail to make it to many households’ dining tables because of cultural restrictions, affordability, and lack of nutritional education. This nutrition crisis is particularly harsh on children. A study conducted by Right to Protein, a protein awareness campaign in South Asia, surveyed mothers of young children in 16 cities in India – and found some very specific cultural nuances in Indian households that keep protein-rich food off the table. For instance, 8 out of 10 mothers believed that the regular Indian diet of dal, rice and roti is enough for daily protein needs. The study identified misinformation as a leading cause to this, and asked mothers to identify protein-rich foods. Surprisingly, only 3 of 11 protein rich products were correctly identified by Indian mothers! They overestimated the protein content in common food items like milk and green leafy vegetables.

The perception of protein itself is perhaps at play here, something that’s understood in this simple finding of the study: 78% mothers believe that people need protein only to boost or regain energy after doing a heavy physical activity. They valued vitamins, carbohydrates and even controlled calorie intake higher than protein.

The secret is to remember to add at least one source of protein in every meal throughout the day. Having only 15g per meal can add up to 60g of protein daily.

Even mid-day meals often fail to hit the 450 calories and 12 grams of protein for primary school children, and 700 calories and 20 grams for secondary school children – as stipulated in the Mid-day meals rules, 2015. Researchers and writers have pointed to the fact that rural households suffer from protein deficiency despite the availability and affordability of protein-rich foods. Hence, nutritional awareness must be prioritised.

There are two kinds of natural protein sources that can be included in your diet: animal-based and plant-based. Some efficient plant-based sources of protein include:

- Legumes

- Beans

- Oats

- Nuts

Some power foods for vegans wishing to add more of the nutrient to their diet are tempeh, tofu, soy milk, and beans, to name a few. For others, animal-based options tend to pack more protein per serving. Adding dairy products like paneer and Greek yoghurt can easily add the required protein requirement for a single meal. Though dietitians recommend not to rely simply on paneer, or one product for that matter. Diversification is a must. Rich sources of protein for non-vegetarians are:

- Lean meat

- Eggs

- Fish and seafood

- Poultry

Red meat is a complete source of protein, but it is best to avoid consuming it daily—some nutritionists would say once in two weeks. Red meat is linked to higher levels of cholesterol, which could strain the heart.

Dr Hukeri asserts that those who still find it difficult to add sufficient natural protein to their diet can turn to supplements. She adds, “The secret is to remember to add at least one source of protein in every meal throughout the day. Having only 15 g per meal can add up to 60 g of protein daily.”

{{quiz}}

Heat stress, weak policies push orchardists to switch to paddy and wheat

In Diwan Khera village of Punjab’s Abohar district, Gursewak Singh, 46, stands amid the remnants of his once-thriving kinnow orchard. By July 2024, he had cleared nearly 3 of his 4 hectares of kinnow plantations, replacing them with paddy fields. The relentless heat had withered his saplings, and he feared the remaining crop might not survive the next growing season.

“It took us eight years to prepare these orchards, and they had been yielding fruit for the past six years,” says Singh, visibly disheartened. “We invested so much time and effort, believing it would sustain us for years. But now, with such a massive loss, we feel broken inside.”

Singh’s plight mirrors the struggles of countless farmers in Punjab’s southwestern region, known as the state’s “kinnow belt.” Covering districts like Fazilka, Ferozepur, Muktsar, Bathinda, Faridkot and Mansa, this region accounts for nearly 75% of Punjab’s total citrus-growing area, with kinnow dominating 93% of the state’s citrus cultivation.

Punjab, the largest producer of kinnow in the country, cultivates the fruit across more than 37,000 hectares in the Abohar-Muktsar belt alone, yielding an annual harvest of 7 to 10 lakh metric tonnes. The ‘Golden Queen’ variant, introduced from California in 1959, has significantly enriched Punjab's agricultural landscape, dominating over 48% of the state's fruit cultivation area and diversifying its crops.

Kinnow growers have created a niche for Punjab in the horticulture sector. Still, the rising temperatures, inadequate irrigation, fungal attacks, and an increasingly unpredictable climate have compelled many farmers to abandon their kinnow orchards, once considered a lucrative crop. Locals estimate that nearly 607 hectares of orchards have been uprooted in Diwan Khera village alone. In the Fazilka district, orchardists report losing 20-50% of their fruit-bearing trees in 2024.

Also read: At this mango museum in Gujarat 300 plus varieties thrive

Farmers in Abohar, the largest kinnow producers in Punjab, cite inadequate irrigation as a critical issue plaguing their orchards. Between February and May—a crucial period for fruit development—a sizable area in the district failed to receive sufficient canal water. Nearly 100 villages in Abohar and its surrounding areas, located at the tail end of the state, are bearing the brunt of this shortage.

Raman, a farmer from Gidranwali village, recently cleared 16 hectares of kinnow orchards. He explains: “The months of March and April coincide with the annual closure of canals for maintenance. This is precisely when flowering and fruit setting in kinnow orchards begin, and the lack of timely irrigation disrupts the entire cycle.”

Similarly, Singh says, “We only need proper irrigation for 2 to 3 months during the flowering and fruit-setting stage, but the state government has consistently failed to ensure even that.”

In the two southern Malwa districts, groundwater is largely saline and unsuitable for irrigating kinnows. Farmers in this semi-arid region rely heavily on canal water for irrigation, with the Sirhind feeder canal—supplied by the Sutlej River—serving as a vital economic lifeline for agriculture. However, delays in water delivery during critical months have severely impacted yields, with farmers reporting a steady decline in production over the last four seasons. Poor canal management has destroyed the region’s economy, with orchards now bearing only 15-20% of the average per-acre yield of 100-150 quintals.

We weren’t even getting fair prices for our yield, and now, with the heat this year, the saplings have started dying even after harvest. At this rate, we fear our orchards will be completely gone in the next 1-2 years.

The irrigation crisis in Punjab’s kinnow belt has been further compounded by extreme summer temperatures, which have reached unprecedented levels in recent years. Ashok Madan, a seasoned farmer from Gidranwali who has cultivated kinnow for nearly two decades, shares his ordeal: “We weren’t even getting fair prices for our yield, and now, with the heat this year, the saplings have started dying even after harvest. At this rate, we fear our orchards will be completely gone in the next 1-2 years.”

Dr. HS Rattanpal, Principal Horticulturist at Punjab Agricultural University, weighs in on the issue. While he refrained from commenting on the adequacy of irrigation, he says: “Attributing crop failure solely to heat may be an oversimplification, as it’s not necessarily a long-term trend. The typical life cycle of kinnow plants is 10 to 15 years, and many trees are likely reaching the end of their productive life span.”

Singh even attempted to replant less than a hectare of land with kinnow after uprooting the old trees, assuming their demise might have been due to their natural lifespans. However, the saplings planted in March 2024 couldn’t withstand even two months of scorching heat and withered away.

%20copy.webp)

Also see: The banana republic

Additionally, the kinnow is a year-long crop, often vulnerable to pests such as mites at various stages of its growth. Kamlesh, another farmer from Diwan Khera, says that his 1.6 hectares of orchard land, which took eight years to cultivate, was destroyed because of pests in 2024. “We planted Bt seeds (or genetically modified seeds to kill certain insects) as it was promoted by the government, saying that it wouldn’t require much spraying or maintenance. But now, the plants have been infested with pests,” he says.

He further says that he even approached the government’s horticulture department in Abohar to show the affected plants. However, they, too, confirmed that there was no solution and that the saplings were bound to die.

In January 2024, kinnow farmers in Fazilka took drastic measures to crush nearly 50 harvest trailers under tractors to protest against collapsing prices and unsustainable market conditions.

Farmers in Abohar revealed that pre-harvest contractors are purchasing their yield at an average price of ₹10 per unit in 2025. These contractors, in turn, sell the produce to wholesalers at rates ranging from ₹21 to ₹25, highlighting a significant markup in the supply chain.

Over the past two seasons, kinnow prices have been consistently low, with an average of ₹6 to ₹11 per kg in January 2024 and ₹6 to ₹10 per kg in December 2023.

Punjab Agro Industries Corporation Limited (PAIC), a government enterprise in Punjab that promotes agricultural development, is set to introduce orange-based gin and process 4 lakh litres of kinnow juice. However, farmers have noted that local processing plants often use surplus or substandard fruit, rejecting good-quality kinnows and offering as low as ₹6 per kg.

Meanwhile, the Punjab government has reintroduced kinnow as a part of the weekly fruit distribution in the mid-day meal scheme for government schools, effective 1 January, though in the past years, repeated flip-flopping between promises and actual implementation has occurred. Under this initiative, it is estimated that nearly 19 lakh students across 19,120 government schools will consume approximately 3 lakh kgs of kinnow each month.

However, farmers in the kinnow belt remain uncertain about how schools will procure the fruit this year. The previous year, PAIC directly purchased kinnow from farmers and distributed it to schools. This year, schools are sourcing the fruit from local retailers instead. As a result, farmers fear they will not benefit directly from the programme, with the primary profits likely going to retailers instead of producers.

An economist from the Department of Economics and Sociology at Punjab Agricultural University, who spoke on anonymity, highlighted that kinnow production in Punjab has averaged around 12 lakh tonnes annually for over a decade. However, this production level is far more than the domestic market can absorb, and limited export opportunities have made the crop increasingly unviable for farmers.

The economist points out that kinnow also faces significant barriers in the international market. “The major problem is that kinnow has no export demand beyond Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and it lacks a global export code, further limiting its appeal in other countries,” they say.

This stagnation in market expansion, combined with oversupply, has left farmers grappling with poor returns and dwindling profitability.

Also read: Kashmir’s apple farmers are ditching Delicious for dazzling

Experts suggest that if farmers sell their kinnows in January and February, they can only secure about ₹10 per kg, as this period typically coincides with a bumper crop. However, by using cold storage from December to February and holding off sales until March to May, farmers can tap into a time of reduced supply and higher demand, potentially earning better prices for their produce.

Additionally, for kinnows to be competitive in international markets, investments in better infrastructure, such as waxing and cooling stations, are necessary. Waxing, which helps extend the fruit's shelf life, is already being done at regional processing plants. However, farmers argue that the cost of waxing—which ranges between ₹3 and ₹3.5 per kg—is not justified by the minimal increase in the fruit’s value. This financial burden is further exacerbated by the lack of subsidies for the process, making it an unsustainable option for many farmers.

In an effort to revitalise Punjab's agriculture and move away from the traditional rice-wheat system, several expert committees have recommended the diversification of crops. However, the state's neglect of its kinnow farmers has led many to return to the more familiar paddy-wheat monoculture. If urgent action is not taken, the kinnow belt could face the same fate as Amritsar, which lost its pear cultivation to aggressive urbanisation.

A fresh take on farming that connects growers and eaters

Beejom, a sustainable farm in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh, cultivates a diverse range of naturally grown produce, including black turnips, violet broad beans, black rice, millets, legumes, oilseeds, herbs, and fruits. Established in 2014 by lawyer Aparna Rajagopal, it started on a piece of leased land in Noida before expanding into its own space. The farm operates on a community-supported agriculture (CSA) model, where urban consumers subscribe to seasonal produce baskets, embracing the farm’s ebb and flow. In addition to selling grains and dry produce at a weekly farmers’ market, Beejom welcomes visitors for weekend farm brunches, serving fresh, homegrown meals while fostering direct engagement with customers.

Beejom illustrates the CSA model in India, linking farmers and consumers through seasonal produce subscriptions. Customers embrace the unpredictability of harvests while supporting sustainability and enjoying fresh, chemical-free food. This system strengthens local food networks and reduces dependence on commercial supply chains.

CSA embraces a shared dedication to creating a more localised and fair agricultural system. It enables farmers to prioritise sustainable farming practices while ensuring their farms remain productive and profitable. Rooted in personal connections, CSAs strive to strengthen communities through a shared focus on food. It is a farming approach where consumers subscribe to seasonal produce, directly backing farms and sharing the rewards and risks of cultivation.

Unlike traditional agriculture, which depends on intermediaries, CSA fosters direct connections between farmers and consumers. Subscribers commit to the farm’s yield, accepting natural variations caused by weather or pests. Many farms adopt organic, permaculture, or biodynamic methods to enhance soil health and biodiversity. Some also engage members in farm activities, deepening their connection to food production. By prepaying for seasonal shares, consumers receive a variety of produce while gaining insight into farming challenges, ensuring small farms a steady income and financial security.

Also read: Farmer’s Share offers a model for boosting farmers' income

The shift towards online food and grocery services has altered consumer behaviour, making it challenging for small businesses like Beejom to sustain themselves. With more people opting for takeout and delivery instead of home-cooked meals, the demand for fresh ingredients has declined. To address this, Beejom actively engages customers by preparing and selling meals made from their own produce and sharing recipes through WhatsApp groups. The farm also advocates reviving Indian millets and traditional foods to promote food security, health, and sustainability. By incorporating solar energy, biogas, rainwater harvesting, and vermiculture into its everyday functioning, Beejom can be self-reliant in its waste management, electricity generation, and water access. Dedicated to grassroots efforts, it collaborates with farmers to transition to organic farming, emphasising that access to clean and nutritious food is a fundamental right.

“The group has 30 consumers from the city, who give us a list of produce that they prefer, and every Friday and Tuesday, we deliver a mix of vegetables and seasonal fruits to them,” says Deepa N, a young farmer from Kariyappanadoddi village in Karnataka. She works under the Mayuri Vanashree Shakti Okkuta, a self-help group (SHG), which is part of an initiative started in April 2024 called ‘Kai Thota’ (“kitchen garden” in Kannada) by the Buffalo Back Collective (BBC). The Buffalo Back Collective was founded 12 years ago by Vishalakshi Padmanabhan, who has dedicated herself to discovering and safeguarding rare, ancient grains and seeds. The core philosophy behind her organic store is shaped by the food values she was raised with, minimising waste and appreciating every resource. She and her husband left their corporate jobs to purchase land in Kariyappanadoddi, 30 km from Bengaluru, where their journey began.

The Buffalo Back Collective is an organic farming collective designed to create mutual benefits for farmers, consumers, and the environment. It retails its products at an outlet in Bengaluru. All the consumers are members of the consumer federation created for the Collective, which mainly comprises people who are worried about food systems and want to make better choices, but cannot grow their own food.

Under the Kai Thota initiative, women from an SHG have leased a 1-acre plot to cultivate crops, allowing consumers to subscribe to 1,200 sq ft sections for a fixed fee. Farmers oversee cultivation, estimate yields, and deliver fresh produce twice a week while maintaining direct consumer engagement. “We set up the whole format for the farmers, including a sowing calendar, the pattern and how to manage seasonal produce, surpluses and deficits,” Padmanabhan says. The idea was to involve women SHGs in directly growing vegetables for consumers.

Also read: Regenerative farming: Solution to climate change?

Recent trends show a rising interest in CSA among Indian consumers, fuelled by a greater awareness of health, environmental sustainability, and the need to support local economies. This change aligns with a global movement toward more localised and transparent food systems. Navadarshanam and Farmizen, both Bengaluru-based, and Solitude in Auroville, are among the several CSA initiatives striving to develop sustainable and meaningful solutions that benefit both farmers and consumers.

Sahaja Samrudha Organics was established in 2010 under the Producer Act. This provision enables the formation of “producer companies” (legally recognised groups of farmers/producers who work together for production and procurement to enhance their incomes), allowing farmers to collaborate in production, processing, and marketing while leveraging collective benefits. It operates on a distinctive model of being entirely owned by organic producers dedicated to environmental preservation while offering various nutritious and sustainable food products. “All the farmers working with us are also shareholders of the company. We procure from the farmers and sell their produce; we ensure that we pay a premium price to the farmer, the annual profits go back to the farmers in the form of patternised bonus, and we also pay them a dividend based on their shareholding with us,” says Somesh B, CEO of Sahaja Samrudha Organics in Bengaluru.

There are several essential features to CSA, which are a win-win for both the producer and consumer, and the environment. “Production planning is much easier for a producer or producers' collective if they have steady and predictable consumer community support,” says Kavitha Kuruganti, a social activist with the volunteer group ASHA Kisan Swaraj. According to her, stable prices help the budgets of both the producer and the consumer. Very often, market options for a producer become restricted due to a lock-in period or clause with creditors. The way most CSA models operate, even the financing requirements of the producers are smoothened out, and more market options open up. For the consumer, safe food is assured in a verifiable manner.

Also read: Farmers demand a fair shake with minimum support prices

“What’s happening these days in the name of CSA is that they are only an investment on the land, and this is nothing but real estate or a business model. Real CSA happens when consumers can interact with the producers, and directly buy from the producers,” says Dr. G. V. Ramanjaneyulu, founder of the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture in Hyderabad. The Centre researches agroecological farming practices and their effects while supporting farmers and consumers in successfully shifting to organic methods. He believes it becomes challenging when consumers approach it as merely a business opportunity, as this mindset undermines the core purpose of producing clean food and fostering a meaningful connection between farmers and consumers.

.avif)

CSA initiatives face many challenges, such as consumers' lack of awareness of the model, making it difficult to establish a loyal customer base. Small-scale farmers struggle with startup costs, ongoing expenses, and fluctuating demand, which threaten long-term sustainability. Moreover, managing storage, transportation, and timely delivery of fresh produce presents logistical challenges, which, when coupled with unpredictable weather and seasonal fluctuations, affect crop yields, leading to inconsistencies in supply.

Now 79, Abdul Kareem guards his thriving creation with care

Nearly five decades ago, in a remote village in northern Kerala, a young man made an audacious decision to transform five acres of barren, rocky land into a forest. The odds were stacked against him. The sun was merciless, the soil was unyielding, water was scarce, and the villagers mocked his ambition. But Abdul Kareem was undeterred.

In 1977, he planted his first saplings, only to watch them wither and burn under the relentless heat. Yet, he refused to give up. With steely determination, he replanted. This time he carried water on his motorbike to nourish the fragile saplings. Nature tested his resolve again, and almost every plant perished. However, one tree—a wild Maruthu, or Arjun tree—stood tall against the odds. This lone survivor became his beacon of hope.

Undaunted, Kareem expanded his mission. Over time, he acquired an additional 27 acres of barren land and continued planting. Slowly, the landscape began to change. By the year 2000, the once-sterile land had been transformed into a thriving forest, bursting with biodiversity. Remarkably, he never used fertilisers or engaged in weeding, allowing nature to take its own course.

The forest, now a sanctuary for numerous bird and animal species—including hornbills, green pigeons, wild hens, peacocks, wild boars, monkeys, snakes, and jackals—stands as a testament to one man's unwavering perseverance.

My forest needs my personal attention, far more than my own children do. Children grow on their own, but a forest demands constant care.

Also read: How an Alappuzha coir exporter nurtured a one acre forest

Now 79, Kareem remains the guardian of his creation, which has been fittingly named ‘Kareem’s Forest.’ Living in a humble home nestled within the greenery, he has forged an unbreakable bond with his surroundings. “My forest needs my personal attention, far more than my own children do. Children grow on their own, but a forest demands constant care,” he explains, justifying his choice to stay within its embrace.

Originally, the land had a single well that yielded around 500 liters of water on a peak summer day. However, as the forest thrived, the well was rejuvenated, storing over 10,000 liters of water daily during summer. Unsurprisingly, the forest became his home, providing his family with crystal-clear water, unpolluted air, and a naturally cool climate.

Yet, Kareem candidly admits he was unaware of these benefits when he first embarked on his mission. “I created this forest for myself. Back in the ’70s and ’80s, I knew nothing about conservation.” At that time his only dream was to build a home in a serene, tranquil retreat, far from the hustle and bustle of city life. It was the heartfelt longing of someone who had once cherished nature but had to leave it behind to make a living.

After completing Grade 12 in 1964, he moved to Mumbai to earn a living. He worked as a labourer in a private dockyard for four years before returning to his hometown, Nileswaram. During the Gulf boom of the early 1970s, Kareem recognised a major business opportunity and established a travel and placement agency to recruit job seekers for the UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. He also traveled extensively to the Gulf countries during this time.

{{marquee}}

Despite his busy schedule, he nurtured a dream of creating his own Kaavu, or sacred grove. "Back in school, I would escape to the nearby Kaavu whenever I had free time. The dark woods fuelled my imagination, and I felt truly alive," he recalls.

And that wasn’t the only time that Kareem felt one with the forest, as a child. He remembers, many times, looking at the hilltop near his home engulfed in flames. The fire swallowed up whole trees and little creatures, and Kareem asked his mother: who set the forest on fire? His mother explained the practice of slash and burn to him. He would watch birds flying, wondering where they were going. He became fascinated with trees, mountains and birds alike.

Years later, he would find this serenity again, in his own forest. In fact, his time in the sweltering lands of UAE played a role in the cool refuge he built back home. He experienced the scorching heat right down to his bones–something that inspired him to create a forest. But it wasn’t just the heat: in the 1970s, Kareem saw Sheikh Zayed plant flowering trees and lawns in the sprawling deserts of Dubai–even the soil had to be brought in from Iraq. Then why couldn’t he do this in Kasargod?

His dedication has not only revitalised the land but has also had an astonishing impact on the village of Puliyamkulam, located 45 km east of the district headquarters of Kasaragod. Once plagued by acute water scarcity, the village now flourishes with abundant groundwater reserves. “The forest has raised the water table. Every well along its periphery brims with water throughout the year,” Kareem says.

No city or hotel in the world can match the serenity of my forest. These days, I find urban settings and air-conditioned spaces suffocating. I long to be amid nature.

His bond with nature is deeply personal. The melodious chirping of birds fills his mornings with joy. “I feel like they are talking to me,” he says. “They grow restless if I am away for more than two days. When I return, they gather around me. I make sure they have fresh water to drink. They repay me by bringing in new seeds, enriching the biodiversity of my forest.”

Also read: Tarachand Belji is turning farmers into eco-warriors

Today, Kareem’s Forest is a lush sanctuary, home to over 800 varieties of plants and shrubs, forming a self-sustaining ecosystem. But the transformation extends beyond the land. It has reshaped him, too.

Once a frequent traveller who enjoyed the luxuries of city life while working in the UAE’s travel industry, Kareem now finds peace only in nature’s embrace. “No city or hotel in the world can match the serenity of my forest. These days, I find urban settings and air-conditioned spaces suffocating. I long to be amid nature,” he says.

His commitment has not gone unnoticed. Global leaders, scientists, and renowned personalities have praised his work. Among them are former US President Barack Obama, former Vice President Al Gore, UAE ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, and Indian superstar Amitabh Bachchan. In 2000, India’s Green Revolution pioneer, Dr MS Swaminathan, visited Kareem’s Forest. “I dedicated a large tree to him,” Kareem recalls. “Even today, scientists and researchers come to explore and learn from my forest.”

Kareem’s remarkable journey has not only transformed a barren landscape but has also found its place in academic curricula. The Kerala education department has included his story in the Class 6 Malayalam textbook, while the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) features it in the Class 4 syllabus, inspiring young minds across the country.

His efforts have grown beyond India and gained colourful global recognition. Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, has chosen Kareem’s Forest as a model for greening, and universities in India and abroad have made his work a subject of study. Even the Indian government, along with various agricultural and forestry departments, is now exploring ways to replicate his pioneering efforts in other arid regions.

Also read: How the 'makrei' sticky rice fosters love, labour in Manipur

Despite his growing fame, Kareem remains true to his principles. His forest welcomes visitors, but there is one strict rule: no plastic. This stems from a personal tragedy. “In 1997, my cow died after ingesting a discarded plastic bag that once held salt. It was a wake-up call. Even today, I actively collect plastic waste. What disheartens me most is that even educated people are polluting the environment with plastic,” he laments.

For Kareem, environmental conservation is not just about planting trees. “Not everyone can plant a tree, but everyone can contribute in their own way. We all should strive to save our dear planet,” he says.

(Image Credits: Sandeep S, Sreejith M)

Procurement and milling delays force them to burn their stubble

In October 2023, thousands of farmers in Punjab protested by holding a chakka jam–blocking major roads–in the cities of Sangrur, Moga, Phagwara, and Batala. The protests, organised by the Bharatiya Kisan Union, were in response to significant delays in paddy procurement and fines issued to farmers for stubble burning. Farmers found guilty of stubble burning owe Rs.10.55 lakhs in fine–but this isn’t all. The Punjab police has lodged 870 FIRs and marked red entries in the revenue records of 394 farmers.

The protests came right after a summon by the Supreme Court. In October, as the winter grew chillier in the north, the air quality in Delhi sunk to lethal levels. The AQI averaged at 234 in October, and it would jump another hundred points in the next month. The state and central government ramped up their efforts to control pollution and improve air quality–and in the same month, the Supreme Court criticised Punjab’s role in Delhi's pollution, summoning both Punjab and Haryana’s state officers to court. The states responded by immediately fining farmers.

But how much does stubble burning in Punjab contribute to Delhi’s worsening air quality?

Air pollution in Delhi and the NCR is driven by multiple factors, particularly human activities in densely populated areas. Key contributors include:

Delhi’s topographic location in the Indo-Gangetic plains also makes the situation worse.

During the post-monsoon and winter months, cooler temperatures, lower mixing heights, inversion conditions, and stagnant winds trap pollutants, leading to higher pollution levels in the region. The problem is worsened by episodic events like stubble burning, firecrackers, firewood burning in the nights, etc.