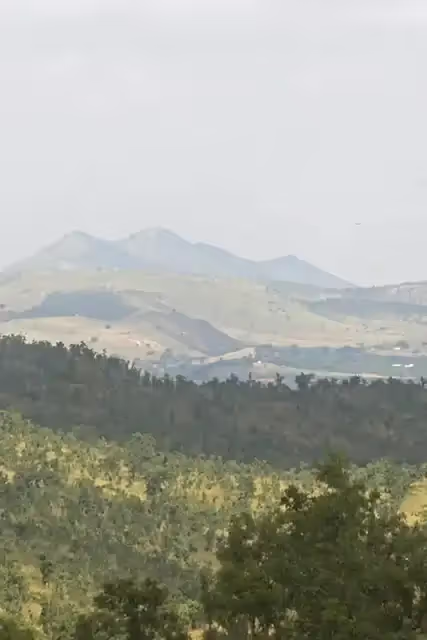

Collective effort steered by the Timbaktu Collective revived a grassland

India’s natural resources are vanishing at an alarming rate. Over the last few decades, a third of the country’s wetlands have disappeared, and grasslands have seen similar losses in just ten years. In the face of little to no government intervention, local communities have stepped up to protect their land and livelihoods.

One such effort is Kalpavalli, a 3,000-acre grassland in Andhra Pradesh. Once barren, this land has been restored through collective action—proving how much can be achieved when people unite to care for nature. In Kalpavalli’s open plains, sunlight pours down unbroken by day. By night, moonlight turns the landscape silver.

The bush camp is remote, with no electricity or mobile networks. As we sit around a bonfire, Chiranjeevi, coordinator of Timbaktu Collective’s Kalpavalli programme, lets us into the story behind the landscape. Thirty years ago, the land was lifeless and forgotten. When CK Bablu Ganguly and Mary Vattamattam, the founders of the Timbaktu Collective, arrived, they were met with scepticism. Tall and lean, Ganguly didn’t fit the local mould, and villagers doubted his intentions. But he and Mary stayed on, building trust by visiting farms, sharing meals, and listening to the community’s concerns.

By 1992, their efforts began to bear fruit. Ganguly established Vana Samrakshana (forest conservation), a group devoted to the restoration of 125 acres of degraded land. Grass began to grow again, and soon enough, the shepherds returned with their sheep. Nine kilometres away, in Shapuram, shepherds brought their animals to graze on the recovering grasslands. But this led to conflicts. Nearby, in Mustikovila, villagers claimed the land as theirs. They had already formed the White Swan Conservation Committee in 1985 to protect grasslands.

“Last year, 82,000 livestock grazed here,” Chiranjeevi says. “In 2022, the figure rose to 100,000.” In a region where rainfall is erratic, the survival of both, shepherding and farming, hinges on the health of the land and the whims of the weather.

By 1995, other villages started to follow Kalpavalli’s lead; three more formed groups to protect their shared land. Together, they built a system that benefits everyone. As Chiranjeevi puts it, this isn’t just about the land; it’s about life–for the soil, the grass, the animals, and for people, too.

A growing movement

Kalpavalli has come a long way. Today, it works with 11 villages, each with its own forest conservation group. When the project started, there were barely any trees–no shade, no forests, just a few scattered trees and patches of grass. Now, after years of hard work, Kalpavalli is home to 400 types of plants, 130 bird species, and 22 mammals.

The project is run by a cooperative with 15 directors who meet every month to plan the next steps. Their main goal is to raise awareness about the local environment. They run programmes in schools to teach children about conservation and train adults to see how protecting the land can benefit their lives.

In 2015, they set up a bush camp to support their mission. It brings in income and serves as a mobile learning centre. Each year, more than 1,000 children visit to learn about the plants and wildlife that now thrive in Kalpavalli.

Persistent challenges

The story of Kalpavalli is one of hope and resilience, but it hasn’t been without its struggles. Climate change and the pressures of development remain. Moreover, the watchers safeguarding the 3,500 acres of rare grassland earn no money for their efforts. There’s no direct reward—no payments for patrolling the area or ensuring its safety. What drives them is their trust in the Timbaktu Collective, a group that has supported these communities for decades. The watchers’ work involves ensuring trees aren’t felled, gathering seeds for planting, and meticulously tracking the number of grazing animals. These records, in turn, serve as a vital health check for the ecosystem.

In 2011, Kalpavalli faced one of its biggest challenges: the arrival of windmills. For years, the area had no roads. It was so remote that Bablu and Mary had to park their car five km away and walk the rest of the way. The windmills brought with them roads, but at a cost. Trees were cut, wildlife was disturbed, and hills were dug up, causing soil to wash into downstream tanks, silting them up.

The villagers decided to act. Backed by the Kalpavalli Cooperative and the Timbaktu Collective, they took their case to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) and won. A Rs 50 lakh compensation was promised, but as the land is officially common property, the funds went to the Forest Department and were spent elsewhere. Still, the victory ensured no windmills could be built inside the conservation area again. Now, they stand on the fringes of the grassland.

Meanwhile, land prices in the region have been climbing steadily, tempting some to claim pieces of the precious grassland as their own. But Kalpavalli, a rare savanna grassland, stands protected—not by fences or laws, but rather the villagers who call it home.

Kalpavalli is not just a beautiful place. The rare savanna grassland is home to species that are disappearing in other areas. For example, the critically endangered Indian grey wolf has been spotted here–a group of seven at one time. Sloth bears and leopards also roam these lands.

What truly sets Kalpavalli apart is its model of care. The community owns and manages the grassland, with the Collective providing organisational support and training. Everything else—preservation, monitoring, and repair—is carried out by the people themselves.

Nature’s reservoirs

Beyond sheltering wildlife, Kalpavalli supports nearby villages in critical ways. The grassland absorbs and stores rainwater, feeding seven downstream tanks. These tanks are lifelines for farming and daily life. When the grassland thrives, water levels rise, securing livelihoods.

But the balance is delicate. In 2023, a harsh drought left just enough water for the grass to survive. This followed three years of good rainfall, which had allowed the ecosystem to recover. Another hurdle is fires during the dry season, but villagers worked together to create firelines and extinguish flames before they spread.

Kalpavalli’s story is one of resilience. Droughts, fires, and encroachment are constant threats, but the community’s dedication proves that grasslands are far from wastelands. They’re vital biomes, as crucial as forests and wetlands.

Explore other topics

References

.png)

.png)