Saritha S. Balan

|

November 1, 2025

|

6

min read

Kerala’s crackdown on errant pharmacies is curbing antimicrobial resistance

Kerala’s action against the sale of antibiotics without appropriate prescriptions has now inspired Telangana

Read More

Kerala’s action against the sale of antibiotics without appropriate prescriptions has now inspired Telangana

In November 2024, Kerala hit a remarkably unique milestone by logging a reduction in antibiotic sales to the tune of over Rs. 1000 crores. Over the years, the state has strengthened its Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) intervention through a multi-pronged approach, slashing the consumption of antibiotics by 20-30%, according to a statement by Health Minister Veena George.

A significant decision that contributed to this result was taken three years ago, when the state government resolved to suspend or cancel licences of pharmacies selling antibiotics to customers without a doctor’s prescription. This year, the crackdown gained strength: in June, the licences of 450 pharmacies were suspended and five were cancelled, for not adhering to the given direction.

The impact of this drive is wider awareness that is prompting people to act. “After the COVID-19 pandemic, people would buy antibiotics using old prescriptions if any symptoms recurred. But now, people have now become aware that they should not be consumed without a doctor’s prescription. The awareness against unchecked antibiotic use has spread to a vast majority of people, though I won’t say it has reached everyone,” reveals a pharmacy owner whose establishment is based in Pettah, Ernakulam. He adds that the purchase of medicines using outdated prescriptions has been considerably reduced now.

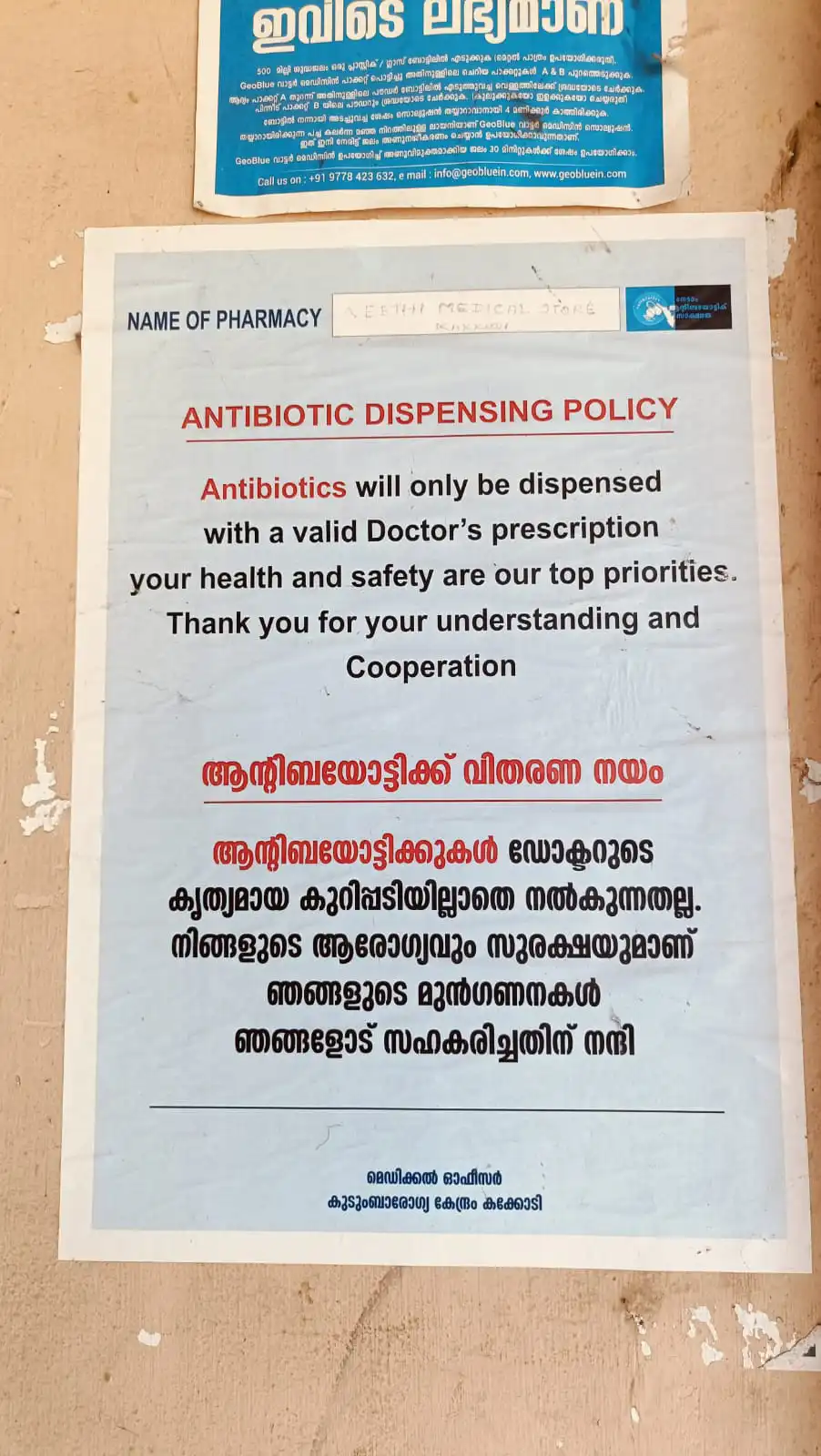

Every pharmacy must clearly display a poster that reads ‘antibiotics not sold without a doctor's prescription’; strict consequences await those who don’t.

There are more than 30,000 retail and wholesale medical shops in Kerala, which are reportedly the focus of ongoing awareness classes for pharmacists. “Medical shops were the core of the campaign, making it their own and putting up the posters on their walls, perhaps because the state has a high literacy rate. People needed no explanation but the posters,” says Dr. Sujith Kumar K, Kerala Drugs Controller. He is referring to the mandate that every pharmacy must clearly display a poster that reads ‘antibiotics not sold without a doctor's prescription’; strict consequences await those who don’t.

Dr. Kumar adds that the Drugs Control Department is working to launch the Sentinel Pharmacy framework to provide accreditations to pharmacies that follow key performance indicators. “These will be model pharmacies, and they will be provided colour codes to be identified as such.” In 2024, the state government announced that this accreditation would enable pharmacies to play a part in disease surveillance and tracking outbreaks by reporting drug purchases and unusual patterns in usage.

AN Mohanan, the President of the All Kerala Chemists and Druggists Association State (AKCDA), underscored that the AMR drive had indeed made a dent. “By and large, medical shops don’t sell antibiotics without a prescription now. Kerala is a progressive state, and the medical shop owners are convinced about the consequences of unchecked sales,” he says.

Another pharmacy-centric action has been the introduction of surprise raids in retail chemist shops by the Kerala Drug Control Department. In fact, even the general public has the power to make a change: the state provides a toll-free number where you can lodge complaints if you see a medical shop selling antibiotics without a prescription. These raids fall under Operation AMRITH (Antimicrobial Resistance Intervention for Total Health), a key project that has enabled several other initiatives since its launch in January 2024.

“The sale of antibiotics now is like that of narcotics, not available without a prescription, and monitored during raids by inspectors of the department. Now, there are regular raids under Operation AMRITH,” the Kerala Drugs Controller says.

Also read: Add crisis to cart: Why instant delivery and antibiotics don't mix

Patients are now more easily convinced when advised to avoid using antibiotics, says ENT specialist Dr. Divya PK, who is the Medical Officer of the Primary Health Centre (PHC) at Koodaranji, Kozhikode. “The use of antibiotics at the outpatient wing has reduced, and patients can’t buy from pharmacies without a prescription. However, constant effort is needed to keep motivating people; the pace should not slow down when a new program is launched,” she adds. Dr Divya was instrumental in transforming the Kakkodi Family Health Centre (FHC) in Kozhikode into an antibiotic-smart hospital. To do this, the Health Centre successfully followed and implemented all of the 10 guidelines issued by the state on curbing the overuse of antibiotics, becoming the nation’s first such hospital.

We follow the exact prescription, and medicine is sold again only if the doctor has suggested a repeat purchase. We are aware of the consequences of unchecked use of all kinds of medicines, not solely of antibiotics.

Despite the government’s proactive stance, a major challenge is that buying only prescribed antibiotics has not gone down well with non-Keralites residing in the state. “They show us prescriptions sent to them via WhatsApp, and the doctors (from their home states) encourage us to sell medication without a physical prescription,” reveals the Ernakulam pharmacy owner quoted earlier. Worse yet, buyers ask for two or three tablets, which chemists like him don’t encourage. “We follow the exact prescription, and medicine is sold again only if the doctor has suggested a repeat purchase. We are aware of the consequences of unchecked use of all kinds of medicines, not solely of antibiotics,” he asserts.

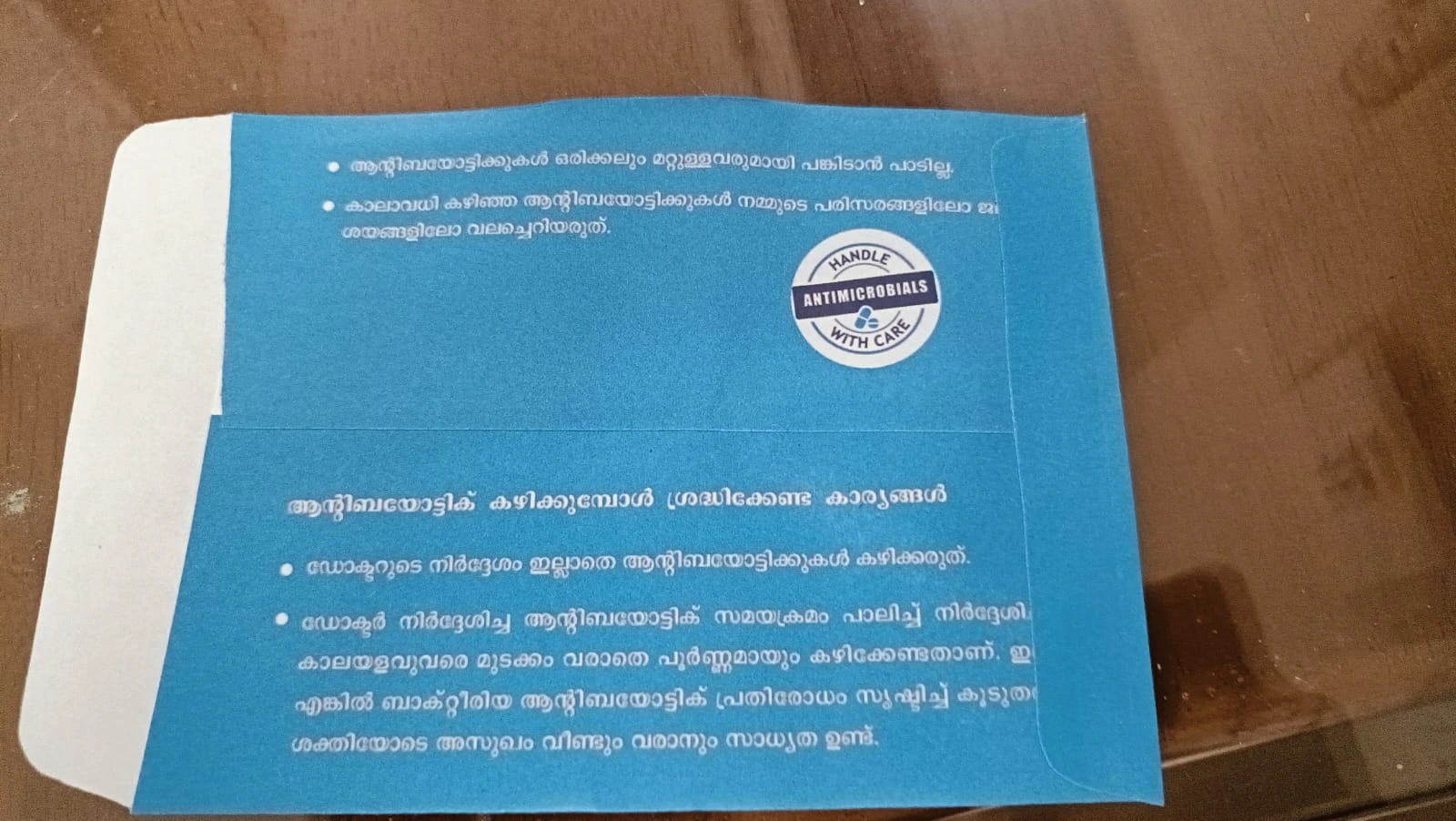

AN Mohanan addresses the government’s direction to sell antibiotics in a blue cover. The mandate dictates that all antibiotics be sold in a blue-coloured bag, so that they can be easily identified. This applies to all medical stores, pharmacies and hospitals. Mohanan specifies that this decision may not be practical because the blue bags aren’t provided by the government. “The Kerala government should hold meetings with us before coming up with regulations, taking us into confidence. Certain things, like selling antibiotics in a blue cover, cannot be made mandatory because of the practical difficulties involved,” he explains. There have been instances where pharmacy licenses have been suspended for selling two or three tablets without a prescription, he notes. “However, when we speak against the unchecked use of antibiotics in our forums, there is a positive impact,” he says.

The impact has carried over; following the suspension of Kerala’s pharmacies in June, the Telangana Drug Control Administration (DCA), too, conducted a state-wide crackdown on its pharmacies. Raids across 193 establishments revealed widespread non-compliance: shops selling antibiotics freely without prescriptions, sales in the absence of qualified pharmacists, and without a proper record of the medicines sold. The raids have spurred the DCA into action, which has indicated a zero-tolerance policy.

In fact, even the general public has the power to make a change: the state provides a toll-free number where you can lodge complaints if you see a medical shop selling antibiotics without a prescription.

Even in the strongest of Kerala’s districts, a major cause of worry is that awareness against antibiotic overuse stands at 40% which demands augmented actions, says Dr. Aravind R, who heads the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram. Standardised metrics are used to measure this progress, like those set by the World Health Organization (WHO). Dr. Aravind R adds: “The state has achieved the WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) criteria of the WHO. Another criterion set by the WHO is that 70% of antibiotic use should be from the Access category.”

Dr Aravind is referring to the category system set up by the WHO to monitor antibiotics, called the AWaRe classification. It has three groups: Access, which includes first-choice antibiotics because they treat common infections and have a lower resistance potential; Watch, a group of antibiotics with higher resistance potential that should only be used for specific, limited infections; and finally the Reserve group, which includes last-resort drugs that should only be used to treat infections caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria, and are highly likely to further AMR. “Yet another milestone to achieve is the WHO’s direction to reduce AMR-associated deaths by 10% by 2030,” he adds.

Also read: How drug-resistant tuberculosis is bringing life to a halt in India

It is not enough to merely address the accessibility of antibiotics that are newly purchased; the extent of antimicrobial resistance is also defined by the usage of old antibiotics. Leaving unused strips and bottles of these drugs around poses risks because consuming them beyond the stipulated period can lead to further illnesses and increased resistance. The AMR intervention in Kerala recognises this, and the state has put into motion–through early pilot projects–the Programme on Removal of Unused Drugs (PROUD). In recent years, it has renewed this programme to sharpen the scope. The programme now collaborates with the Haritha Karma Sena or the Green Task Force, which is made up almost entirely of women engaged in the state’s waste management drive. Trained members of this group conduct door-to-door collection of unused medicines, including antibiotics.

“The idea is to first make people aware, and then act. We collected 28 tonnes of unused drugs from commercial establishments and households under the Corporation and the Panchayat. The change will be big when this is implemented across the state,” Dr Kumar adds.

Also read: Sivaranjani Santosh’s fight to knock mislabelled ORS off the shelf

Additional inputs from Neerja Deodhar and Anushka Mukherjee

Edited by Neerja Deodhar and Anushka Mukherjee

Payment-first flows and one-minute teleconsults are making antibiotic access too easy—and antimicrobial resistance harder to fight

It starts the way it often does in Indian cities now: a work night before a big day, a meeting on the calendar, and an app on your phone’s home screen. A cough that has lingered for a week, the worry it might get worse, and the desire to be functional tomorrow. You open a quick‑commerce app that promises groceries in ten minutes and medicines in under an hour. A search bar, a suggestion chip for “cough & cold,” and then the thing you are not supposed to be able to buy without due process: an antibiotic.

You add it to the cart. The funnel is clean: pay now, and then choose between ‘upload prescription’ or ‘free teleconsult’. The order clock starts ticking only after payment. The clinical check is somewhere in the future.

This inversion—commerce first, medicine later—isn’t a glitch. It’s how some of India’s fastest‑growing platforms have decided to sell regulated drugs. And it lands in a country primed to say yes. For decades, the neighbourhood pharmacist has doubled as nurse, counsellor and sometimes, general physician. WhatsApp forwards pass for medical advice. Leftover tablets live in kitchen drawers. Antibiotics, especially, have become reflex—a strip for a cold, a child’s fever, “something viral.” We have learned to treat them like household tools. Apps now make that reflex kick in faster.

Also read: How drug-resistant tuberculosis is bringing life to a halt in India

To see how quickly that reflex turns into a delivery at the door, I ran a simple test over three days in Bengaluru on six leading platforms: four quick‑commerce marketplaces that fulfill orders through partner pharmacies, and two inventory‑led e‑pharmacies that ship from their own licensed stores. I attempted to buy three common Schedule H antibiotics, including Augmentin. By law, these drugs require a doctor’s prescription and pharmacist oversight because inappropriate use can drive resistance, trigger serious side effects or lead to dependence. I also tried one Schedule H1 drug—Levoflox (levofloxacin)—which calls for stricter rules: pharmacies must record the buyer’s details, the prescriber’s name and the quantity sold, and preserve those records for three years.

This inversion—commerce first, medicine later—isn’t a glitch.

Each attempt succeeded. Most deliveries arrived within minutes; some in six, most under fifty. One took a day and a half, but the ordering experience was the same.

The architecture of the checkout explains why. The apps present a fork: upload a prescription or get a “free” teleconsult. In practice, both paths flip the sequence that any responsible pharmacist or physician would expect. The user must pay for the medication before any meaningful verification—be it a prescription check or a teleconsultation—is initiated. This design makes the medical justification a reversible afterthought, while the sale is a locked-in certainty.

When I uploaded prescriptions, some platforms accepted documents that were outdated, mismatched in dosage, or obviously not for the drug in the cart. By law, under the Drugs & Cosmetics Act and the Pharmacy Act—reinforced by a 2015 circular that extended these rules to online sales—every prescription is supposed to be reviewed by a pharmacist, the same as when you hand one over at a physical counter. But most approvals happened silently, and it remained unclear whether a pharmacist actually looked at my prescriptions. In one case only, a pharmacist did review my prescription, caught the discrepancy, called me to reject it, and then set up a teleconsult with a doctor who approved the order within minutes.

This design makes the medical justification a reversible afterthought, while the sale is a locked-in certainty.

The teleconsults themselves were brief. Audio calls, often under a minute, with three to four questions, sometimes leading. “Is your throat hurting?” when the order was for Azithromycin. “Any allergies?” “Name and age?” Vague complaints—“ear pain,” “ran out of medicines,” “my doctor gave this months ago”—were enough for both Schedule H and H1 drugs. The digital prescriptions produced after these calls were inconsistent: different diagnoses for identical symptoms, different dosage schedules for the same medicine, and patient names that didn’t match the account holder. All doctors were located in cities and small towns far away. The antibiotics shipped anyway.

On August 11, the All India Organisation of Chemists and Druggists (AIOCD), representing 1.24 million chemists nationwide, sounded the alarm for its own reasons and some of the public’s. They wrote to Union Home Minister Amit Shah, naming big quick‑commerce brands and accusing them of delivering Schedule H, H1 and X drugs within minutes while “skipping mandatory prescription verification”. The group flagged “ghost prescriptions”—medicines approved without genuine verification, including late-night approvals for distant patients—and warned that easy access to controlled substances could fuel drug abuse among the youth.

These failures are embedded in three business models that are now vying for the pharmacy market.

Inventory-led companies sell from their own licensed pharmacies and manage inventory, emphasising—at least on paper—pharmacist-verified supply over speed. Marketplace e-pharmacies don’t hold their own retail licences. They connect customers to a network of licensed pharmacies that dispense the drugs. Finally, quick-commerce platforms plug into this system as logistics/tech intermediaries, often tying up with marketplace players or licensed pharmacies to deliver in minutes.

Speed is loyalty and friction is the enemy. A pharmacist who calls back to ask a hard question becomes a drop‑off point in a funnel.

This distinction is not determinative for the safety of the consumer. All three models delivered antibiotics with equal ease and equal lack of meaningful checks. None of this is surprising if you’ve watched Indian e‑commerce and quick commerce over the last five years; the race is to become the app you open daily. Average order values for medicines are higher than those for groceries, with repeat rates often hitting 50% monthly, creating the sticky customer relationships that platforms desperately seek to make investors happy.

Speed is loyalty and friction is the enemy. A pharmacist who calls back to ask a hard question becomes a drop‑off point in a funnel.

This would be just another story about tech breaking things if antibiotics were ordinary goods. They aren’t. Misusing antibiotics—taking them when not needed, stopping early, or taking the wrong one—kills off the easy-to-kill bacteria and strengthens the survivors, who multiply and share resistance traits.

The result shows up in labs: about 37% E. coli isolates (the most common bacterial pathogen) tested by the Indian Council of Medical Research no longer responded to imipenem, a class of medication doctors try to save for severe infections. Routine infections now drag on for longer, cost more, and force doctors to burn through classes of drugs they would rather hold back. As reliability fades, risks are mounting across the system since surgeries, chemotherapy, and intensive care all depend on antibiotics working.

What makes this risk sharper is the mix of drugs that online pharmacies keep in stock. The World Health Organisation classifies antibiotics into three groups: Access (broad-spectrum, lower resistance potential), Watch (higher resistance risk, should be restricted), and Reserve (last-resort drugs). Its stewardship goal is that at least 60% of global antibiotic use come from the Access group. But a study of Indian e-pharmacies found over 70% of the antibiotics available online fell in the Watch category, with Reserve drugs also on offer—widening the scope for misuse.

Of the four antibiotics I tested, three fall in WHO’s ‘Watch’ category, with only Augmentin in the safer ‘Access’ group.

Dr Sharad Khorwal, a general physician in Noida, has watched this change at the bedside. “Diseases we once handled with oral antibiotics now often need intravenous therapy, sometimes third‑ or fourth‑generation antibiotics. When I started my medical career forty years ago, typhoid was infrequent and responded to antibiotic pills. Today, most cases need 10–15 days of IV treatment. The tablets that worked then are just out of action.”

When I shared what medicines I was able to order via the apps, he’s blunt: “Azithromycin, Augmentin, Levofloxacin are very potent antibiotics. But today people are using Azithromycin like Vitamin C, not knowing that it’s one of the medicines required to treat drug-resistant typhoid. Look at the harm being done.”

Also read: The looming crisis of post-antibiotic era

The deeper problem is cultural muscle memory. For many families, time and money are tight. The clinic is far, but the pharmacist is near. For many, self‑medication is not a corner case; it’s a starting point. Instant delivery apps didn’t create that habit, but they are scaling it.

And the state hasn’t kept up. The Drugs & Cosmetics Act, 1940, and its Rules, 1945, are the bedrock. They created Schedules H and H1, mandating a prescription for sale. The Pharmacy Act, 1948, regulates the profession. These laws were written for a world of physical counters and paper trails. But a 2015 circular by the Drugs Controller General of India did clearly state that all online and offline sellers must meet the same licence/pharmacist/prescription obligations.

In 2018, the health ministry drafted e-pharmacy rules as an amendment to the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945, to address online sales, requiring central registration and mandating pharmacist verification. Seven years later, those rules have still not been notified. Besides, they failed to cover marketplace players, focussing only on e-pharmacies. In late 2022, the government introduced the Drugs, Medical Devices and Cosmetics Bill, a law intended to replace the 1940 Act. It explicitly brings e-pharmacies under its regulatory ambit by requiring mandatory licensing. This, too, remains in draft form.

This regulatory inertia has forced courts to intervene: the Delhi High Court has repeatedly directed the government to formulate rules, while the Madras High Court has clarified, in 2024, that existing pharmacy laws apply equally online, but has allowed online sales to continue pending final notification.

The newly enacted Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 further complicates matters with few specific safeguards for health data, leaving prescription images and medical histories vulnerable on corporate servers. “When you come to my shop,” notes Rajiv Singal, General Secretary of AIOCD, “I don’t store your private health data. I don’t tell anyone what you have. Why should an app have a database that stores a record that you have tuberculosis or diabetes? That’s your secret, that’s your private matter.”

The 2020 Telemedicine Practice Guidelines updated during COVID-19 already provide a framework for remote consultations. They require a proper patient history and documentation, and video calls as the doctors deem necessary. But, as my testing showed, the perfunctory, sub-one-minute audio chats used to approve antibiotics on demand violate this spirit.

These regulatory gaps and delays have been good for the apps. They have enabled the surge of the marketplace model, particularly attractive to quick-commerce platforms backed by foreign direct investment (which faces restrictions in inventory-based pharmacy models). By acting as intermediaries rather than licensed dispensers, these platforms keep liability and capital needs lower, while scaling fast.

Like many physicians, Dr Khorwal believes instant delivery of prescription medicines, especially antibiotics, is fundamentally incompatible with responsible use. “A 1:1 physical examination of the patient is compulsory.” When asked about the way forward if we assume digital access to medicines is here to stay, he stands his ground. “For OTC medicines and supplements, online delivery is okay. For the elderly, for the immobile, teleconsultation is also fine for the first line of treatment. But nothing can replace an in-person examination by a doctor.”

Younger doctors are more open to the need and inevitability of digital innovation, but also draw the line when it comes to the nature of 1:1 consultations. “Teleconsultations for prescription medicines need to be via a video call at the very least, otherwise it’s impossible to diagnose acute or chronic conditions that actually require antibiotics,” according to Dr Rahul Arora, a general physician based in Delhi.

Given the government’s unwavering focus on the National Digital Health Mission, it’s safe to assume online delivery of medicines is here to stay. And it undeniably solves real access problems. The goal then is to innovate towards safety, and the technical fixes aren't that hard to imagine.

For OTC medicines and supplements, online delivery is okay. For the elderly, for the immobile, teleconsultation is also fine for the first line of treatment. But nothing can replace an in-person examination by a doctor.

Two Bengaluru-based product managers (PMs) in quick commerce described how they would design this safeguard, if speed wasn’t the only factor.

These safeguards could be coded directly into checkout flows. But some problems like preventing the same prescription being reused across multiple platforms need regulation and enforcement. That is where product fixes end and the law must step in.

For instance, the UK requires online and distance-selling pharmacies to check the patient’s identity using photo IDs, facilitate robust two-way clinical exchanges between the patient and prescriber (particularly if antimicrobials are in play) and almost everyone uses the same central digital rail–the NHS Electronic Prescription Service. Prescribers (GPs and other authorised clinicians) and pharmacy teams sign in with smartcards. Each prescription is created, signed, dispensed and logged in one system, tied to named professionals. This combination of strict checks and shared infrastructure blocks anonymous approvals, makes re-use across outlets hard and gives regulators a clean audit trail.

A good place to start for India, as Kazim Rizvi–founder of The Dialogue, a Delhi-based think tank at the intersection of tech, public policy and society–writes, is finalising the 2018 e-pharmacy rules and explicitly covering marketplace/intermediary platforms. And then, operationalising them: make apps verify every seller by having pharmacies upload their licence to their backend; mandate audit trails linking each order, prescription, verifying pharmacist and dispensing pharmacy; and, require platforms to retain those trails and teleconsult notes for audits.

But some problems like preventing the same prescription being reused across multiple platforms need regulation and enforcement. That is where product fixes end and the law must step in.

Finally, ensure every order is billed by the licensed pharmacy (not the app) with a traceable cash/credit memo listing the patient, drug/strength, quantity, prescriber and Rx date, pharmacist registration, timestamp, order ID, and the pharmacy’s licence number.

The nuance here is that none of this kills speed for most orders. The number of people who order antibiotics on any given day is a tiny slice of the total volume. Platforms can dial up safeguards only for those products and only at the point of risk. Delivery times might increase by a few minutes or hours for antibiotic orders, but that seems like a fair trade for public health.

Also read: Meet the minds investigating bugs lurking in poultry

The bell rings. The last order in my three-day test arrives. A paper bag with a strip of tablets inside, no invoice, no prescription.

I don’t take the pills. The strip sits unopened because this was a test of the pathway, not a cure. But the ease with which I could have taken them—the way the apps made it feel normal—is the point.

{{quiz}}

Lack of adequate nutrition increases vulnerability to TB and prolongs recovery from it

At a government-run tuberculosis (TB) hospital in Mumbai’s Malad suburb, 29-year-old Usha and her mother wait patiently for their turn to get medicines. Uma, who is 50, was diagnosed with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (DR-TB) a week ago at a private clinic. She wears a weary look on her face.

"I have been coming to this hospital for three days for these medicines, leaving my work aside—with no doctor in sight. My mother's condition has worsened over a week, with a persistent cough and fever due to delayed treatment," Usha says.

At another government-run hospital in the nearby suburb of Kandivali, frail-looking, 40-year-old Ashok—the sole breadwinner of his family of three—waits. Diagnosed with TB nearly seven years ago, he now fears a relapse. “I was coughing heavily and unable to breathe when I was first diagnosed. I completed my treatment and recovered, but recently, I have begun experiencing chest pains again and fear that a relapse is imminent."

In 2018, the Government of India launched the Nikshay Poshan Yojana to provide monthly monetary assistance of Rs. 500 to TB patients for adequate nutrition through centralised Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT). The amount of the aid was raised to Rs. 1,000 earlier this year. At the time of the scheme’s launch, Ashok—the resident of a small tenement in Mumbai—didn’t reap any of its benefits because he was unaware about the Yojana. And though he received timely medication from the government hospital, managing his nutrition as per the doctor’s advice was challenging, as both his wife and son depended on him. He believes that the government should provide sufficient financial assistance and rations to patients suffering from the disease.

Globally, India leads in DR-TB with 1,35,000 cases of MDR/RR TB annually due to a lack of rapid diagnoses in low-resource settings, posing a significant constraint on DR-TB treatment.

Many vulnerable socio-economic populations in India, especially informal and migrant workers, are unable to afford the luxury of rest and proper nutrition without remaining reliant on daily wage work. This is despite schemes like the Nikshay Poshan Yojana, as patients in need remain unaware about their provision.

The United Nations defines TB as a bacterial infection primarily affecting the lungs, but it can also affect the brain and spine. It is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. The World Health Organization states that India has the highest number of TB cases worldwide; the country reported 26.07 lakh tuberculosis cases in 2024, with Uttar Pradesh reporting the highest cases at 6,81,779, followed by Maharashtra at 2.25 lakh cases. Mumbai contributed 60,051 cases to the state's numbers in 2024.

The death rate from multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), specifically, hovers around 20% in India—higher than the global average of 17%. These figures depict dire on-ground realities; for context, the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP) aimed to eradicate TB by 2025, five years ahead of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target of 2030.

| Types of DR-TB | |

|---|---|

| Mono-resistance | Resistance to a single first-line anti-TB drug (medication which is given when TB bacteria is susceptible to the medicine) |

| Poly-resistance | Resistance to more than one first-line drug, excluding both isoniazid and rifampicin |

| MDR-TB | Resistance to both isoniazid and rifampicin |

| XDR-TB | MDR-TB plus resistance to a fluoroquinolone and at least one of the second-line (drugs used when resistance is developed to first-line drugs, or when patients cannot tolerate them) injectable drugs, such as kanamycin, amikacin, or capreomycin |

The different types of DR-TB are mono-resistant, poly-resistant, MDR-TB, and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB). Around 3.2% of new DR-TB cases are MDR-TB/rifampicin-resistant—they resist first-line drugs, or the first round of drugs that is administered when the bacteria still responds to medication. When the bacteria resists this first round, like in the case of DR-TB, the infection is fought with a different combination of medicines: second-line drugs, which can be more toxic, more expensive and less effective.

Globally, India leads in DR-TB with 1,35,000 cases of MDR/RR TB annually due to a lack of rapid diagnoses in low-resource settings, posing a significant constraint on DR-TB treatment. As a result, it is estimated that around 56% of MDR-TB cases remain undiagnosed in India.

The WHO guidelines recommend using rapid molecular tests like GeneXpert to diagnose DR-TB instantly, offering detection in less than two hours, compared to conventional culture-based methods, taking several days or weeks. However, these services are scarce in the rural hinterlands of India, especially the Northern states.

Only one in three DR-TB patients worldwide receive high-quality care, the WHO notes. In India, which contributes over 27% of global cases, DR-TB presents a significant public health problem, as patients often require changes in their treatment plans, usually linked to poor treatment adherence in peripheral and resource-limited zones. Drug-resistant tuberculosis cases increased by 36% in Mumbai between 2015 and 2017.

In 2022, the WHO recommended using a shorter six-month regimen called BPalM, consisting of four drugs, to treat DR-TB—compared to the standard 18-24 month regimen—as it has a global success rate of 85%. This positive statistic comes with better treatment outcomes, reduced mortality rates and less infectiousness in recovery. BPalM is also significantly more cost-effective—and the reduced treatment costs ensures more access to patients.

However, India has adopted this regimen conditionally, and private practitioners don't have access to prevent its misuse. In Mumbai, a hotspot for drug-resistant TB, only 144 patients have been given the BPalM regimen this year on a pilot basis.

Also read: Antibiotic overuse is turning your gut against you

There are several types of TB. It can be inactive (latent TB): the infected individual does not have symptoms and cannot spread the infection, which is suppressed by treatment. It can be active: the infected individual can spread the infection through droplets in the air.

Active TB can be treated and even cured, but it is a particular kind of active TB that scares doctors and patients alike: the forms that are drug-resistant, meaning one or more anti-TB drugs administered to the patient show no effect on the bacteria. It fights back.

Dr. Indu Bubna, a Mumbai-based pulmonologist with over 20 years of experience, says, "DR-TB is a form of TB that does not respond to the primary anti-TB drugs, particularly isoniazid, and rifampicin because of incomplete or incorrect treatment. DR-TB is more toxic and requires lengthier treatment." According to Dr Bubna, the challenge emerges when a patient is diagnosed with XDR-TB (extensive drug-resistant TB)—a more severe form of DR TB—making the case more complex with the failure of second-line drugs.

Though India is widely considered the ‘pharmacy of the world’, TB patients in the country suffer due to the lack of medicines.

"In India, before visiting a government Directly Observed Treatment (DOT) centre, patients tend to self-medicate, delaying diagnosis. Often, treatment is started based on X-rays without the appropriate tests because of strained finances," Dr Bubna adds. Drug shortages during the patient's treatment can also cause interruption, making the disease more resistant.

TB is known as the "disease of poverty" because the chances of contracting it are furthered by factors such as malnourishment as well as the lack of air and sunlight in cramped residences. An airborne disease, it is caused only by inhaling infectious droplets from the air. TB is not caused by any changes in diet, or anything in the water, but these are still really important factors in the context of the disease. Malnutrition renders the immune system weak; a malnourished person is more at risk to get infected by TB—in fact, it increases the risk by 13.8% per unit decrease in the body mass index (BMI). The body’s ability to respond to treatment is severely affected, as poor nutrition can prolong recovery. Moreover, some people develop resistance to TB over time, and this can be due to the lack of access to proper nutrition and prescribed, timely dosages.

Malnourishment is also a risk factor in converting latent TB to active TB, and this weakness in immunity also makes patients less likely to recover once they do contract the disease.

Dr Bubna points out that the incidence of TB is now increasing in the middle and higher income sections of India’s population as a result of one specific reason: these sections follow rigid, traditional diet regimens that are often lacking in nutrition. "TB is not just about malnourishment—it also manifests in patients who don't eat food on time and travel in overcrowded spaces. Furthermore, people with HIV, diabetes and those who indulge in drug abuse are also vulnerable," says Dr Bubna.

Malnutrition renders the immune system weak; a malnourished person is more at risk to get infected by TB—in fact, it increases the risk by 13.8% per unit decrease in the body mass index (BMI).

The prevalence of TB can be linked clearly to a lack of access to nutrition as well as a flawed approach to nutrition. Dr. Bubna explains, “While the Public Distribution System (PDS) and mid-day meal programs provide calories and iron-fortified staples like rice and atta, these diets often lack adequate protein and key micronutrients. Protein is especially important because it helps rebuild tissues, strengthen muscles, and restore immune function. Micronutrients such as zinc, vitamin D, vitamin A, and B-complex vitamins are also vital for immune defense and healing, but these are often missing in the diets of TB patients.” The gap lies in the difference between calorie sufficiency and nutrient adequacy: patients often get food that satiates hunger, but does not provide the quality of nutrition required for faster recovery and reduced relapse risk.

"In India, most people lack either vitamins B12 and D, or protein,” Dr. Bubna points out. This is also reflected in the burden of disease that India carries: we account for around 27% of TB cases across the world. A well-balanced diet rich in proteins and vitamins, like iron, zinc, B12, and D3, is essential for patients battling DR-TB. Addressing TB care's social and nutritional loop is essential for its elimination.

According to government data, over Rs. 3,200 crore have been disbursed to 1.13 crore TB patients under the Nikshay Poshan Yojana; the government has committed another Rs. 1,040 crores as a 60:40 divide between the centre and states, under the same programme.

The unaffordability of nutrition is a concern for several patients in India. Even with low prices, a healthy diet remains out of reach for nearly 74% of Indians, according to a UN agency report. "Doctor sensitivity also plays a crucial role in wholesome counselling. Without that, the prescription is never complete. Every TB patient should have a protein and iron-rich diet, comprising green leafy vegetables, one fruit, paneer, soya, and several proteins, because they have a high risk of relapse and mortality for DR-TB."

Also read: The warning about antibiotics we should have heeded

To improve diagnostic services, says Dr. Bubna, governments must decentralise testing, improve sample transport, and integrate private labs into the national network—changes that are underway in Mumbai. However, India’s more remote centres lack even basic tests like the Line Probe Assay (LPA), a quick molecular test that presents results within 24–48 hours.

Screening and testing for TB early and accurately is extremely crucial to treatment and recovery from this infection, and there are multiple provisions in place for this. In 2012, the Government of India made TB notification mandatory for both public and private sector healthcare providers. In 2017, the Government of India announced a National Strategic Plan (NSP) to eliminate TB, and set aside a budget specifically for testing. The very next year, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued another order stating that doctors, pharmacists, chemists, and laboratory staff could face jail time if they fail to notify TB cases.

Despite these stringent rules, India contributes approximately 25% of “missing” TB cases globally, as the WHO estimates that approximately 1 million TB cases in India are not recorded annually. A detailed report from IndiaSpend reveals that while the NSP aimed to spend funds on diagnostic equipment, testing kits, and increasing testing in the private sector, they only spent “2.1% of [their] budget (Rs 4.34 billion) on diagnostics up to 2023-24.” While the 100-day campaign to eradicate TB introduced by the centre in 2024 did amp up testing and diagnosis in several states, the overall practice remains uneven in the country. In some places, testing facilities are either defunct or non-existing, like in Haryana—where the only state-level laboratory closed due to lack of support staff—or districts in Bihar, where none existed until 2020. As a result, it is estimated that around 56% of MDR-TB cases remain undiagnosed in India.

Even delayed results of testing pose a threat for this precarious disease. Public health activist and TB survivor Ganesh Acharya draws attention to how delays in test results, even for basic investigations like X-rays, can have negative consequences. "Referrals by doctors at government-run hospitals require a 15-day window to provide services like CT and MRI, making the initial stage more painful for patients with significant out-of-pocket expenditures. Ideally, test results should be available in two hours through the Cartridge-Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (CBNAAT).” CBNAAT is a rapid molecular diagnostic test used to detect TB, which promises quicker results because it’s a fully automated test that analyses DNA from sputum samples. “However, the lack of resources and the staff makes the provision challenging.” Acharya adds.

Despite these stringent rules, India contributes approximately 25% of “missing” TB cases globally, as the WHO estimates that approximately 1 million TB cases in India are not recorded annually.

According to Firoz Shaikh, the general district supervisor for Mumbai's TB department, "The testing facilities for the GeneXpert test—a type of CBNAAT test—are available for free in government hospitals like the Sewri Hospital, Topiwala Hospital, and Shatabdi Hospital in Mumbai." Yet, a glaring concern is that the government department only contacts patients seeking private treatment to complete their treatment on time—a provision largely missing for patients in government-run hospitals, according to Shaikh.

"Usually, patients from higher income groups don't register on the Nikshay portal for the government's DBT transfers. Sometimes, patients receive Rs 1000 monthly for their treatment, but there are times when the amount is released later. To resolve this, patients can download the Nikshay Mitra application and complain using the toll-free number." Shaikh adds that the Nikshay schemes have been relatively successful in Maharashtra compared to other states in India. "The patients respond regularly to avail these schemes in Maharashtra as the diagnosis rate is higher."

Public health activist Acharya rues the lack of accountability within the public sector. “The Nikshay Poshan Yojana is a centralised Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme; I don't understand the reasoning behind delays in payments. Furthermore, I have heard of cases where individuals have received only Rs 500 (half of what they ought to have received).” These gaps are glaring, especially when we consider that a trial held in the states of Odisha and Jharkhand found that adequate food packages given to patients significantly improved their health outcomes.

Challenges in testing and monitoring only add to the financial and emotional burden caused by drug shortages. Though India is widely considered the ‘pharmacy of the world’, TB patients in the country suffer due to the lack of medicines. For instance, essential treatment drugs are unavailable for months in states like Uttar Pradesh. In 2023, a Times of India report found that Pilibhit in Uttar Pradesh was facing a drug shortage, unable to provide for approximately 1,200 frontline TB patients, including 124 MDR-TB patients.

"Skipping a dose on even one day is a big mistake for a TB patient, but there is nothing one can do when the government machinery runs out of medicine. This is a very negative aspect of the program, as it fails to address the systematic gaps for essential medicines," says Acharya.

Dr. Bubna steers the conversation back to patients: understanding the importance of nutrition at home and within families is essential. Immediate digital awareness, volunteers—such as those under the Nikshay Mitra scheme, where people adopt TB patients to aid them with nutrition support until their recovery—as well as the integration of community kitchen services for those without houses or migrant DR-TB patients, the presence of counsellors at clinics—all represent crucial, effective interventions that make patients cognizant of the role nutrition plays in their ailment.

"In rural areas, anganwadis and caregivers can work together to ensure food security, with the availability of fortified food rich in iron, folic acid, and vitamins. If supported with proper nutrition like probiotics and proteins, the side effects of drug doses can be mitigated."

Mehra adds that schemes like the Nikshay Poshan Yojana have made a significant difference but are inadequate in a country where a high-protein diet is costly.

According to Acharya, urban areas like Mumbai’s Govandi suffer more due to a lack of basic provisions such as sanitation and proper ventilation. "The fight is not just about a 100-day awareness campaign. It has to be systematic, with measures like food, sanitation, and open spaces. Political will has to be informed by survivor consultations."

According to Chapal Mehra, a public health practitioner and founder of the forum Survivors Against TB, "Nutritional provisions play an essential role in health security. Those affected by TB tend to belong to the lower-middle class and middle class, and often, the person who is affected is also the primary breadwinner of their family.”

Mehra adds that schemes like the Nikshay Poshan Yojana have made a significant difference but are inadequate in a country where a high-protein diet is costly. "What can one get for Rs 1,000? We can't say that the government is not trying, but it's not enough, and the amount under the Yojana should be increased to Rs 2,000 for basic provisions."

With inputs from Sijal Sagarika

Also read: Meet the minds investigating bugs lurking in poultry

{{quiz}}

'Farm owners are unaware of antimicrobial resistance's risks'

In 2019, the leading international research journal Science reported a rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in central India. Two years later, the research platform Nature Communications identified wetlands in Kerala as emerging AMR hotspots. However, both studies were based on meta-analyses (a process that compares data from independent studies to draw broad conclusions) or indirect data. Researchers were left puzzled: there really wasn’t enough comprehensive ground-level data to validate these conclusions.

This gap in data motivated a team from the Drug Safety Division of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) – National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad, led by Dr Shobi Veleri, to investigate the prevalence of AMR in poultry.

In 2022, the team launched a study focusing on two states: Telangana and Kerala. The recently published research report revealed that the antimicrobial resistance profile in poultry in central and southern India is evolving with distinct features, thus validating the reports published by the international journals.

However, it stated that the severity of AMR profiles in the samples was relatively lesser than those seen in the poultry from the European Union (EU). AMR profiles from the Indian states have not evolved to the extent seen in poultry farms of the European Union (EU). “This suggests that India still has an opportunity to contain the AMR in poultry by putting in place stringent regulations,” says Dr Veleri, in an exclusive interview with GFM.

He also cautions that many farm owners are unaware of the risks of AMR. “Inadequate regulatory supervision contributes to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics. Overcrowding in farms and inadequate biosecurity protocols allow resistant bacterial strains to spread quickly in poultry populations.”

How did you go about conducting the research?

We collected fresh, warm stool samples from poultry farms in Telangana during July and August 2022, and from Kerala during September and October 2022. Three samples were collected from each farm, separated by at least 3 km. We took a total of 240 faecal samples from 85 poultry farms. As many as 38 of them were located in Telangana, while the remaining 47 were from Kerala. Adhering to the international practice of masking the identity of individual farms, the samples were pooled zone wise. Kerala had three zones: north, middle and south. Telangana had three major mandals surrounding the Hyderabad metropolitan area, which has a large congregation of poultry farms. From the stool, genomic DNA was isolated and genome sequencing was done on an advanced automatic sequencing machine. The output data was analysed by a computer-based programme to avoid human interference.

The study was done by a four-member team from the Drug Safety Division of the ICMR - National Institute of Nutrition from Hyderabad, led by me. Ajmal Aseem, Prarthi Sagar, and N Samyuktha Kumar Reddy were the other members in the team.

What were your major findings from this process?

We identified over 169 distinct AMR genes from the samples. This included high priority pathogens such as E.coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which cause abdominal infections, respiratory tract infections (pneumonia, bronchitis), and urinary tract infections. Notably, southern India exhibited a significantly higher number of resistance genes, compared to central India.

What explains this prevalence of AMR genes in poultry?

All organisms have strong survival instincts. Bacteria, too, have an incredibly fast system to develop resistance against antibiotics that threaten their existence. The more the use of antibiotics, the more chances the bacteria will have to evolve resistance genes.

Antibiotics are used indiscriminately in poultry farms because of the inadequate regulatory supervision. We realised that many farm owners are unaware of the risks of AMR. What compounds the problem is the overcrowding in farms and inadequate biosecurity protocols, which allow resistant bacterial strains to spread quickly in the poultry population.

Environmental factors, too, play a crucial role. Improper disposal of animal waste often leads to the contamination of water sources, which introduces AMR bacteria into the food chain. The proximity of poultry farms to human settlements increases the risk of contact transmission.

How can AMR bacteria spread to humans and the extended environment?

Like most infectious diseases, AMR bacteria can spread through contact: animals to humans and humans to humans. AMR bacteria can also enter the environment through the faeces of humans or animals. A common route for bacterial contamination of the food chain is from faeces via soil to water–and ultimately, the bacteria reaches animals and humans.

Properly cooked food and meat generally degrade 95% of the contaminated bacteria and the DNA in them, except some spore-forming ones. So, avoiding chicken meat is not a solution against the threat of AMR.

The best option is to reduce indiscriminate use of antibiotics.

Also read: The looming crisis of post-antibiotic era

Your study mentions that “the samples exhibited a higher prevalence of gram-negative and anaerobic species”. What does this mean?

Our samples had 44% gram-negative, such as E.coli, Bacteriodes fragiles, Klebsiella pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; and 79% of species were anaerobic, such as Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus. Gram-negative bacteria have an extra layer of cell membrane protection: it’s almost like a helmet which protects your head during bike rides. These gram-negatives, upon acquiring AMR genes, get double protection against antibiotics–making it very difficult to kill them via antibiotics. If they evolve to overcome treatment options, we will be facing a serious health hazard.

The study states that “the severity of AMR in Telangana and Kerala is lesser than European Union.” Does this mean that it’s safer to consume chicken meat in India than in the EU?

We inferred that the severity of AMR profiles in the samples was relatively lesser than those seen in the poultry from the European Union (EU). This is because we could not detect the recently-evolved AMR gene mcr-1, which is resistant to Colistin (a last-resort antibiotic on the World Health Organization’s essential list of medicines to treat AMR) and another newly-evolved resistance gene optrA in our samples. These genes are commonly found in AMR-affected poultry in the EU.

Additionally, the qnr gene, commonly found in the EU, was found at much lower levels in Southern Indian samples. So, AMR profiles from Kerala and Telangana poultry farms have not evolved to the extent seen in poultry farms in the EU. This might be because Indian farmers started using antibiotics much later than their counterparts in the EU. This suggests that India still has an opportunity to contain AMR by putting in place stringent regulations.

How serious is the situation?

AMR is an emerging global threat to the healthcare sector because [if this continues] we will run out of effective antibiotics to treat diseases in humans and animals. The World Health Organization has considered AMR among the top priority in its ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ under the ‘One Health’ practices and principles. The data indicates that AMR genes are in an alarming condition, at least in some regional hotspots in poultry farms. If we miss this opportunity to control its spread, we will be in for a huge health crisis. The findings underscore the urgent need for reducing indiscriminate use of antibiotics through proper stewardship, enhanced biosecurity monitoring measures–and targeted public health interventions to mitigate the growing threat of AMR in poultry as well as its spillage to other organisms.

Also read: What’s lurking in your chicken dinner?

Is it possible to completely avoid the use of antibiotics in the poultry industry?

While it is challenging to completely avoid the use of antibiotics in the poultry industry or any sector for that matter, it is possible to significantly reduce our reliance on them through improved hygienic animal husbandry practices. It is time the poultry industry utilised alternatives to antibiotics, such as vaccines, peptides, and bacteriophages, etc.

Also read: How bacteria evolve and survive antibiotics

{{quiz}}

Undetectable for long periods, its diagnosis remains a challenge

In 2018, Dixit Kundar, a young resident of the Udupi district in Karnataka, paid a huge price for a game of barefoot football in rainy July. The only son of his parents Jai and Pathima, he was admitted to Manipal’s Kasturba Medical Hospital with complaints of high fever, severe headaches, repeated vomiting and trouble with closing his eyes while asleep. Despite medical interventions, his condition worsened as the days passed.

A week after being hospitalised, he succumbed to Melioidosis—a condition that was considered rare at the time. The news sent shockwaves through the public and medical fraternity. Following Kundar’s death, health officials were alarmed by the widespread presence of the causative bacterium, Burkholderia pseudomallei, in the soil, water, and environment of tropical, coastal, and monsoon-prone regions in India.

The bacterium is transmitted through inhalation, small cuts, or ingestion of contaminated water. Kundar had played football in flooded areas near his home, and it is suspected that he may have fallen into a waterlogged field during the game, thus exposing him to the disease.

A 2016 report estimated over 50,000 people contract Melioidosis annually in India, with more than 30,000 deaths. “India was predicted to have the highest burden for the disease (20,000- 52,000 new cases/year with an estimated mortality of 32,000 per year),” reads a 2019 bulletin from the National Centre for Disease Control. Troublingly, over 90% of the total cases in the country have been reported in the last ten years, even as academics predict that since 2005, the incidence of the disease has been underreported owing to misdiagnosis. Globally, the disease affects around 160,000 people each year, causing approximately 89,000 deaths.

Microbiologists believe Burkholderia pseudomallei has been prevalent in India for over a century; it was first described in Myanmar’s Yangon in 1911. “Dixit's death brought attention to a deadly infectious disease that the medical fraternity has issued warnings about since 2005,” says Prof Chiranjay Mukhopadhyay, Director of the Manipal Institute of Virology, who identified the first cluster of cases in 2007.

“It invades cells and destroys them. The infection can be particularly fatal for individuals with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. If left undiagnosed and untreated, patients may succumb within 48 to 72 hours,” Mukhopadhyay adds.

Understanding how India’s geography influences the spread of Melioidosis is critical for developing region-specific prevention strategies.

Fearing an outbreak, a team led by Mukhopadhyay visited every household in Udupi to assess the situation. They collected soil samples, tested drinking water sources, and disinfected stagnant water bodies with bleaching powder, in collaboration with district health authorities. They also urged residents to keep their homes, gardens, and cattle stables clean, as well as advising them to wear shoes when working with soil and water.

Those who work on farms, or even engage in recreational activities in waterlogged areas, are at a higher risk of contracting Melioidosis, warn medical experts. Gardening without gloves, walking barefoot, and consuming contaminated water also increase the risk of infection.

The disease can appear in a manner similar to pneumonia, septicemia, or acute bone and joint infections during the rainy season. In contrast, in the dry season, patients often present with multiple abscesses and skin ulcers.

For years, microbiologists struggled to diagnose Melioidosis due to symptoms that resemble those of common infections such as malaria, tuberculosis, dengue and the flu. This often led to misdiagnoses and delayed treatment. “A delay in identifying the disease can be fatal, as the infection requires specific antibiotic treatment,” Mukhopadhyay explains.

That Melioidosis can remain dormant in the body for years, resurfacing only when the immune system weakens, only adds to the concerns surrounding its diagnosis. “This characteristic makes it a ‘silent killer’ that can strike without warning. The disease can lie undetected for long periods, posing a persistent and hidden threat,” he said.

India's tropical, coastal, and monsoon-affected regions provide ideal conditions for the growth and spread of Burkholderia pseudomallei. While cooler, arid, and high-altitude areas face a lower risk, factors such as flooding, irrigation, and poor sanitation still pose significant threats.

Scientists have found connections between climate change and the spread of Melioidosis—including rising temperatures and more extreme weather events; Burkholderia pseudomallei thrives in warm, humid environments. Higher temperatures and lingering moisture create the perfect habitat for the bacteria in soil. As rainfall and flooding increase, the bacteria migrates from soil to water sources, broadening its spread.

Human intervention, in the form of deforestation, urbanisation, and changes in agricultural practices, also contribute to the spread of the disease. Soil disturbances during the rainy season, combined with strong winds, can release the bacteria into the air, raising the risk of inhalation and infection.

Climate change-induced extreme weather events, such as cyclones and droughts, can significantly alter the dynamics of Burkholderia pseudomallei in the environment. Cyclones bring heavy rainfall and soil erosion, while droughts concentrate the bacterium in soil and water, increasing its virulence during subsequent periods of rainfall. “Understanding how India’s geography influences the spread of Melioidosis is critical for developing region-specific prevention strategies. On the climate change front, raising awareness, improving surveillance, and adopting sustainable practices are essential measures to combat the threats posed by Melioidosis,” Mukhopadhyay says.

To combat the disease's spread, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) launched MISSION: A Multi-Centric Capacity Building Initiative to Strengthen the Clinical and Laboratory Detection of Melioidosis in 2022. The project involves 15 medical centres across 14 states, including Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Sikkim, Tripura, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, New Delhi, Odisha and Rajasthan. The initiative aims to raise awareness about Melioidosis and improve early detection and treatment protocols.

Kasturba Medical College (KMC) in Manipal, a leader in Melioidosis research for the past two decades, serves as the referral centre for the project. The Centre for Emerging and Tropical Diseases (CETD) has developed comprehensive training protocols for healthcare staff, equipping doctors and technicians with the tools needed to diagnose and treat the disease effectively. “Accurate diagnosis is critical for the successful treatment of Melioidosis. This capacity-building initiative aims to empower healthcare facilities across India to identify and manage the disease more efficiently,” Mukhopadhyay informs.

Early diagnosis is essential for effective treatment. “If the diagnosis is delayed, doctors may administer broad-spectrum antibiotics indiscriminately, potentially leading to antimicrobial resistance. This makes proper treatment increasingly difficult. Early and accurate diagnosis is, therefore, vital,” the veteran microbiologist explains.

Greater awareness can be raised if Melioidosis were classified as a notifiable disease, as well as recognised as a neglected tropical disease, he adds. This recognition will increase public awareness and help experts to attract funding and conduct research to combat it. “With the rising number of cases, particularly in tropical regions, we must invest in understanding the disease and developing effective treatments. By categorising it as a notifiable and neglected tropical disease, we can ensure the necessary resources are allocated to combat it, ultimately reducing its impact on affected populations,” he concludes.

{{quiz}}

Research suggests potential gut-brain link in Parkinson’s & Alzheimer’s

Our bodies are home to a vast community of microbes that not only coexist with us but also play a vital role in maintaining our equilibrium, said Dr Bhavana MV, a microbiologist at Manipal Hospitals.

The gut, in particular, houses 90% of the body’s bacteria, which help produce essential enzymes for normal bodily functions. This collection of bacteria-along with archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses–forms the gut microbiome.

The microbiome begins to develop in newborns, as their intestines are initially immature. “As the infant is exposed to various environments and milk, the microbiome develops within 5–6 months,” said Dr Bhavana. “Once it reaches a satisfactory level of maturity, we can introduce solid foods.”

The delicate balance of the gut lining is sensitive to antibiotics. "When we get an infection or illness, it can damage the gut’s protective lining. The food we eat also plays a role, sometimes depleting the good bacteria and giving harmful ones room to grow. As these bad bacteria multiply, they produce polymers that can lead to disease,” said Neha Jain, associate professor at IIT Jodhpur’s Department of Bioscience and Bioengineering.

Evidence suggests that early exposure to antibiotics can disrupt multiple systems, including the gastrointestinal, immune and neurocognitive systems.

“The gut microbiome is linked to various physiological conditions such as weight management, mood disorders and gastrointestinal issues,” said Akanksha Gupta, co-founder of MicrobioTX, a Bengaluru-based gut health startup.

The rise in antibiotic use in recent years has been directly linked to these issues. The antibiotics we take, even just occasionally, can really disrupt our gut. It can take weeks or even months to recover, even after taking the right dose. Some studies show that certain healthy bacteria are still missing up to six months after taking antibiotics. Just imagine the damage caused when antibiotics are used more than necessary.

"The bacteria stay in groups, not individually. They form a community, which gives rise to antimicrobial resistance," explained Jain. She also stated that her lab is looking into how these communities are formed, their composition, and whether a drug can be designed to prevent this formation.

Also read: What’s lurking in your chicken dinner?

Two new studies suggest that Parkinson’s disease might sometimes originate in the digestive tract and travel to the brain, driven in part by a chain reaction involving gut microbes. “Active research has been happening since the last 10 years. However, people have reported in the 80s and 90s that there’s some connection between the gut and the brain,” said Jain.

Researchers suggest that as the concentration of certain microbes increases, movement-related symptoms of Parkinson’s worsen. In those with Parkinson’s, the gut's microbial balance shifts, allowing specific bacterial families to dominate. Among them is E coli, a microbe notorious for causing gut infections.

The studies identified a chain reaction initiated by E coli that leads to abnormal protein clumps forming in the gut. These clumps have also been found in the brains of Parkinson’s patients.

"Most of the beneficial bacteria in our gut play a key role in breaking down the fibre we consume. However, when there’s a change in this balance, healthy bacteria are lost, and small gaps form in the gut lining. This allows harmful bacteria and viruses to take over, leading to a condition known as leaky gut," said Dr Baby Chakrapani, Honorary Director of the Centre for Neuroscience and Assistant Professor.

"The microbes lining our gut are essential for maintaining good health. Overusing antibiotics can destroy these healthy microbes, which can trigger the onset of various illnesses, including neurological conditions," he added.

At birth, microbial populations are transferred to newborns, primarily through exposure to natural vaginal bacteria. This is why vaginal births are usually better for establishing a strong microbial foundation. Babies born via C-section miss out on this initial transfer and need more time to build their microbiome through breastfeeding and diet in the months that follow. This early microbiome plays a key role in building immunity, giving naturally delivered babies an early advantage in gut health.

However, this balance can later be disrupted by lifestyle factors like exposure to pesticides, antibiotics, and even stress. These factors damage the gut lining, often triggering the onset of various health problems.

The microbes lining our gut are essential for maintaining good health. Overusing antibiotics can destroy these healthy microbes, which can trigger the onset of various illnesses, including neurological conditions.

The researcher, who specialises in neuroscience and brain cell studies, said when we think of neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, we usually focus on the symptoms that appear in people aged 50 or 60. But changes in the brain often begin 20 to 30 years earlier, during a pre-symptomatic stage that goes unnoticed. Subtle symptoms may emerge in this phase, and constipation is a common early warning sign. “It’s one of the changes that signals a disease may develop later,” he said.

Our bodies often signal when something is wrong, but sometimes symptoms stay hidden. In such cases, doctors recommend tests to assess gut health. Typically, these tests involve stool samples.

MicrobioTX has introduced a method that uses a simple finger-prick test instead of traditional stool-based analysis. “The Gut Function test uniquely predicts gut bacteria by analyzing metabolites in the blood using a finger-prick sample. By relying on a machine learning model, GFT allows a user to bypass traditional stool-based testing or genomic sequencing to know his gut profile, making it more affordable, less invasive, and faster, with results available within two weeks,” said Gupta.

Our bodies have both good and bad bacteria. Antibiotics don’t know the difference and kill both. It’s like during a riot–when the police try to stop the trouble, innocent people sometimes get hurt too.

The misuse of antibiotics is another pressing health issue. “Antibiotics used to be easily available without a prescription, so people got into the habit of taking them for things like colds and coughs. In the last 5–6 years, India has been working to raise awareness about antimicrobial resistance (AMR), but progress has been slow. Many still think they can take antibiotics whenever they want, but that needs to change,” said Jain.

She has been part of a rural outreach programme to tackle the misuse of antibiotics. “We educated people about what antibiotics do and why they shouldn’t be used unnecessarily. We also explained how overuse can lead to AMR.

“Our bodies have both good and bad bacteria. Antibiotics don’t know the difference and kill both. It’s like during a riot–when the police try to stop the trouble, innocent people sometimes get hurt too. If this continues, the innocent ones are lost. This is what happens when we use antibiotics,” she added.

{{quiz}}

Existing healthcare gaps fuel Delhi’s AMR crisis

As the national capital, Delhi may be India's seat of power, but it doesn't have complete control over its own health--an aspect that is frequently affected by the actions of its neighbours. Be it the thick smog that envelops the capital and brings the life of its residents to a grinding halt during winter, or the hidden manner in which the city ignorantly consumes antibiotic-treated food and water. Similarly, Delhi may not be home to pharmaceutical manufacturing factories, but neighbouring states with such facilities often dump waste into common water bodies. This cyclical fate is unlikely to change, say experts, until the states it shares borders with straighten up their act and have their own action plans in place.

Delhi’s unique predicament calls for unique solutions when it comes to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a crisis identified as one of the top ten global threats to humanity. Antibiotics, our defence strategy against harmful microbes causing life-threatening infections, have disturbed the balance within and without. After the World Health Assembly adopted a global action plan on AMR in 2015, India followed in 2017, and Delhi became the third state to launch its plan in January 2020.

In alignment with the national action plan, Delhi’s own has identified six strategic objectives: awareness and education; laboratory network for early diagnosis and surveillance; infection prevention and control; optimising antibiotics’ use; research; and, lastly, collaboration between national and international NGOs to implement it at the grassroots level, says Dr Sangeeta Sharma, nodal officer for the Containment of AMR for the Government of the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi.

.avif)

Since AMR affects all spheres of life, it is addressed with a One Health approach, where the health of humans, animals, plants, and environments is taken into account in a unified manner. This has posed a bureaucratic challenge--it requires the health, food, animal husbandry, environment, and industry ministries to work together.

As part of the capital’s action plan, doctors, pharmacists, and nurses have undergone training programmes to build capacity, and students and teachers are being educated about antibiotic misuse and resistance. “Often, antibiotics are prescribed ‘just in case’ for conditions like coughs, colds, upper respiratory illnesses, and acute watery diarrhoea, which are predominantly viral and do not require these medicines,” says Dr Sharma, who is also the president of the Delhi Society for Promotion of Rational Use of Drugs (DSPRUD). “In 2022, we launched an integrated diagnostic and antimicrobial stewardship programme to improve diagnosis and reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. So far, we have trained more than 1,000 doctors, 1,600 nurses, and 450 clinicians.”

When it comes to pharmacists, the focus has been tackling self-medication by buyers and preventing over-the-counter sales of antibiotics. “The DSPRUD also undertook awareness drives for the schools urging people to not use medicines without a doctor’s go-ahead and not to buy antibiotics (especially HI1 drugs) over the counter without prescription,” Dr Sharma adds.

Food is not something that the Union Territory produces daily, and neither is most of its poultry. All of it comes from the states surrounding it.

The plan calls for a particular focus on school students, encouraging and training them to spread the word among the general public. “We wanted children to talk to their parents and keep tabs on antibiotic use within their families, as we saw in the case of the firecracker campaign in Delhi, where there was a deeper penetration of the message,” says Dr Ravindra Aggarwal, chief coordinator, AMR, Government of NCT of Delhi.

Over two years, awareness campaigns organised in collaboration with the WHO, DSPRUD, and the National Centre for Disease Control have reached out to 900,000 students and 3,500 teachers. Most recently, a partnership with the non-profit organisation ECHO India enabled over 250 teachers to be trained, across October and November. Discussions among educators have been centred on the identification of misuse and its prevention, with the aim that the teachers will spread knowledge among their students and communities, Dr Aggarwal added.

Also read: Inside Tamil Nadu's battle against AMR

“As a coastal state, Kerala prioritises aquaculture. Whereas Delhi lacks a coast or farmland, thus relying on neighbouring states for food supplies. In that sense, it is a consumption state. Food is not something that the Union Territory produces daily, and neither is most of its poultry. All of it comes from the states surrounding it,” says Dr Robin Paul, a senior veterinarian and consultant at the Food and Agriculture Organization.

The city’s multi-tiered healthcare infrastructure also presents unique challenges. The Union Territory houses a diverse range of healthcare settings, from sub-centres and primary health facilities to super-specialty centres, each with their distinct problems and varying complexities. “The use of antibiotics varies greatly, from minor surgeries to transplants. To preserve the efficacy of antibiotics in life-threatening operations, we need to know which antibiotic to use in the first place,” Dr Sharma adds. The formulation of Delhi’s action plan involves 120 stakeholders from 17 different levels of healthcare to address this multi sectoral and multidisciplinary challenge, she explains.

Also read: Kerala is winning the battle against AMR and how!

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shift in priorities, Dr Aggarwal says, causing AMR to be put on the backburner. “Afterward, we tried but could not set the desired tempo, as leadership at the level of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) in the Delhi government changed.”

Alongside policy, regulation remains a challenge. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI)’s decision to expand its list of flagged antibiotics, and the intent to tighten norms on the maximum residue levels of antibiotics in animal products, has emerged as a silver lining; these new norms will be effective from April 2025.

Dr Vijay Pal Singh, a veterinarian at the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research--Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (CSIR-IGIB), calls attention to the use of antibiotics in animal care--an alarming issue that is understudied. The former joint director at the FSSAI highlights a study conducted at the CSIR-IGIB, which found that dogs in the university's vicinity were completely resistant to the most commonly used antibiotics. Yet, these drugs continue to be rampantly prescribed to animals in veterinary care. “This research, as well as awareness and training programmes to avoid the use of antibiotics in animals, is immensely lagging,” Dr Singh says.

.avif)

Part of the problem stems from the lack of an established and accepted term for AMR-related fatalities. “I may die from multiple organ failure or another condition, but it will not be marked as AMR. It is an orphaned issue that cannot be quantified or named, and thus, the urgency of the threat is overlooked,” Dr Singh adds.

The veterinarian also points to the absence of a unified platform to share data. “One Health is an entirely completely academic exercise at the moment. Each agency--the FSSAI, Export Inspection, and CDSCO--has its own regulations and laboratories.” Thus, these agencies tend to work in silos. Tackling AMR calls for mandatory surveillance to make informed decisions--which could be facilitated by a consolidated platform that keeps various stakeholders apprised of developments. “For instance, if a certain food item contains too many antibiotics, human doctors should be aware [of this] so that they can adjust their prescriptions accordingly,” Dr Singh explains.

As the rolling out of the second National Action Plan nears, Dr Sharma says that firm guidelines will be established. “However, implementing the plan’s strategic objectives is a monumental task. The government alone cannot do it. All sectors, including NGOs, must leverage each other’s strengths to make meaningful progress,” she says.

{{quiz}}

Antibiotic residues in milk reveal regulatory gaps and rising risks

India, the world’s largest producer of milk, contributing 25% to global production, is facing a serious challenge with antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The widespread use of antibiotics to treat cattle infections in the dairy industry is a major driver of this crisis.

“AMR severely hampers the effective treatment of infectious diseases, leading to higher mortality rates, longer hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs,” says Amit Khurana, director of the Sustainable Food Systems Programme at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) in New Delhi.

Over the last decade, India's milk production has grown by about six percent annually, reaching an impressive 231 million metric tonnes (MMT) in 2022-23. The growth highlights the importance of dairy farming to India’s economy, with 18 million dairy farmers spread across 230,000 villages, many of whom are women. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) aims to boost productivity so the country accounts for one-third of global milk production by 2030.