A winner of the Ramsar Award for Wise Use of Wetlands, she learnt her earliest ecology lessons by sketching a river outside her home

Editor’s Note: To work in ecology science and biodiversity conservation in India is to undertake the work of a lifetime. For many, but especially women, this work is as much a career as it is a calling, with challenges that pertain to the job itself—such as reasoning with authorities—as well as their personal journeys and identities. In this series, the Good Food Movement highlights female scientists, activists and community builders whose visions and labour have ensured forests, wetlands, and species across flora and fauna live another day.

Decades before she won the Ramsar Award for Wise Use of Wetlands, long before she cofounded the conservation group Care Earth Trust, and years before she even moved to Chennai, Jayshree Vencatesan, now 65, loved to sit along the banks of the Godavari river and peer into the water.

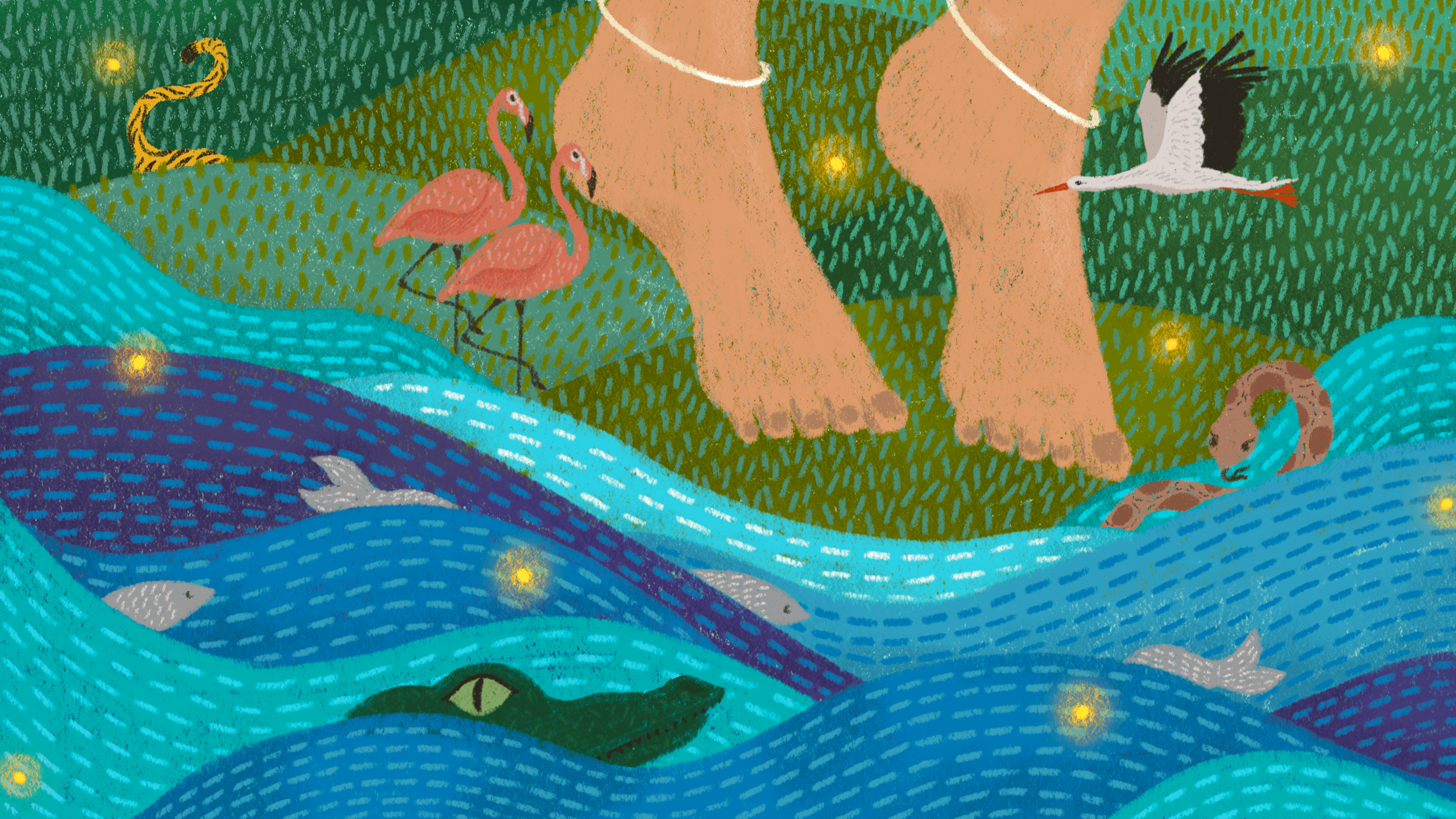

Vencatesan grew up in Rajahmundry, a small town in Andhra Pradesh, and the river was just a short walk from home. She would stare at its ripples and eddies with a notebook and a pencil, watching the Godavari’s colour moult like the skin of a living creature, from cerulean to muddy green to the deep purple of a bruise. Vencatesan loved to draw what she described as the river’s “moods”, and it was in the water’s changing colours that she began to understand them. For example, when the Godavari turned brown with muck, she knew it would flood.

Vencatesan once told her mother to expect the river to rise the following day, and her mom—weary of a child who learned far more outside the confines of a classroom than inside of one—told her to “go do something useful.” “My mother keeps saying, ‘she was a vagabond, and she made a career of being a vagabond,’” Vencatesan says with a chuckle.

Still, Vencatesan was a bit of a paradox—a vagabond with roots. As she grew older and began a career in conservation science, there were plenty of opportunities for her to leave India and never think much about returning, but her father had always implored her to “do the best for your country first.”

Wetland conservation, as Vencatesan notes, is not the most glamorous of endeavours, even if India has lost between one third and one half of these ecosystems since the 1940s, and continues to lose them at a rate of about two-three percent per year.

So, instead of moving abroad, she moved to Chennai, where in 2000 she cofounded Care Earth Trust with ecologist R.J. Ranjit Daniels. The two of them were already well known in their fields; Vencatesan had earned a PhD researching the links between gender and biodiversity in the Kolli Hills, where she met and decided to work with Daniels while he was studying birds and other creatures in the area. But the organisation’s focus on reviving wetlands didn’t inspire anyone to help get the group off the ground. Wetland conservation, as Vencatesan notes, is not the most glamorous of endeavours, even if India has lost between one third and one half of these ecosystems since the 1940s, and continues to lose them at a rate of about two-three percent per year.

“We were broke,” Vencatesan says. “It was miserable, let me tell you that.”

Also read: The Chitlapakkam Rising story: How a Chennai community saved a lake

Growing pains

Vencatesan and Daniels had one desk and one chair between the two of them. He sat at the desk because she said she didn’t mind the floor.

The pair went on like this, more or less, for a decade. They had no problem securing one meeting after another with government officials to talk about marshes and the work that Care Earth Trust could do to rejuvenate them. Still, it wasn’t the government that Vencatesan and Daniels had to convince.

More and more people were moving into Chennai, and apartment complexes—along with the roads and all the accompanying infrastructure—were rising almost anywhere land was available, and often even where there wasn’t. Real estate companies and government workers were happy to dump mud and rocks into wetlands until the soft, watery mud was firm enough to build on.

“Every road, every infrastructure project that has come up in Chennai has been at the expense of wetlands,” says Vencatesan. “It was the stupidest thing the government could do, to put it mildly.”

“Every road, every infrastructure project that has come up in Chennai has been at the expense of wetlands,” says Vencatesan. “It was the stupidest thing the government could do, to put it mildly.”

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world.

Turning points

As the new century wore on, more people in Vencatesan’s adopted city began to see her point. Drought became a constant worry in Chennai, in part because the city’s ravenous 21st century expansion eradicated many of its water bodies and that meant less and less water found its way underground, where it could be pulled up to irrigate crops or to drink from in areas of the city that aren’t connected to the piped supply. The Care Earth Trust began to receive some work, and then came the 2015 floods that ravaged the city.

Wetlands prevent flooding in the same way they prevent drought: by providing water with a place to go. Vencatesan was one of the first scientists to write about how the fragmentation of Chennai’s 50 sq km Pallikaranai Marsh forced excess rainwater into the streets, and by 2015, so many of Chennai’s waterbodies had been paved with asphalt and concrete that the torrent of rain from that season’s seemingly never-ending monsoon had no choice but to swamp the city’s homes. Vencatesan says she had long thought that Chennai wouldn’t wake up to the ecological damage it had done to itself until a flood swallowed the affluent neighbourhoods, and that year proved her to be correct. International agencies began pouring money into recovery efforts, including wetland rehabilitation. Suddenly, Care Earth Trust was busy.

{{marquee}}

(A look into the avian biodiversity of the Pallikaranai Marsh. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Shanmugam Saravanan, Amara Bharathy, Sudharsun Jayaraj, Timothy A. Gonsalves)

Vencatesan often finds herself giving lectures to institutes in and around Chennai, and she’s always looking for women interested in ecology who strike her as willing to challenge authority.

Ten years on, the group is still coaxing city marshes back to life, often with the help of communities who come looking for guidance in rehabilitating their own local wetlands. Each of these projects is a drawn-out process. At first, only a few community members care. Then their families start to show an interest. Then some friends. Over four or five years, Vencatesan says, birds start to reappear. Spotted deer show up. Finally, the marsh is back. These sorts of successes steadily built up the reputation of Care Earth Trust and Vencatesan, and in March 2025, she became the first Indian to receive a Ramsar Convention grant when the group honoured her with its ‘Wise Use of Wetlands’ award.

.jpg)

Care Earth Trust remains grounded in the work that Vencatesan and Daniels initiated at the turn of the millennium, and the group now pays and trains young women to safeguard Chennai’s ecological balance well into the future, allowing them to grow into scientific careers away from the prejudices of men. Vencatesan often finds herself giving lectures to institutes in and around Chennai, and she’s always looking for women interested in ecology who strike her as willing to challenge authority.

“Women should be given the strength, the capability, the power, and the backup to function to their full potential,” she said.

Care Earth Trust has also recently begun to publish classroom material centred on wetland conservation, including a book released late last year called Be My Happy Place, which helps students explore their own urban ecologies.

Marshes, lakes, and rivers have always been a happy place for Vencatesan, and she hopes that kids will find themselves there just as she did.

Art by Jishnu Bandyopadhyay

Produced by Nevin Thomas and Neerja Deodhar

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

At what rate does India lose its wetlands every year?

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.png)

.avif)

.avif)