These climate-smart ancient structures have lessons for India’s present and future

Editor’s note: The last two decades have been witness to the rapid and devastating march of unchecked urbanisation and climate change in India’s cities. Among the first victims of this change is freshwater and access to it—from rivers which sustained local ecosystems, to lakes and groundwater which quenched the thirst of residents. In this series, the Good Food Movement examines the everyday realities of neglect and pollution. It documents the vanishing and revival of water bodies, and community action that made a difference.

In Gujarat, the state with the largest coastline—which is flanked by the Arabian Sea on one side and patrolled by flowing rivers like the Narmada, Sabarmati, Tapi, and Mahi on the other—residents harbour a dichotomous relationship with water. Life in the state adheres to the whims of the water—the paucity and the abundance of it.

In ancient India—and Gujarat—water conservation was a great architectural preoccupation, driven by the necessities of agricultural dependence, the harsh realities of unpredictable monsoons, and extreme climate fluctuations. Among the most spectacular architectural innovations to emerge from this preoccupation were stepwells, that date back to the 7th century and are considered some of the earliest forms of decentralised water harvesting structures.

Decentralised water typically refers to water management where water services—collection, treatment, distribution, and wastewater management—are handled locally at a small scale, rather than through one large, centralised facility serving an entire city or region. They appeared as man-made reservoirs, punctuating the arid landscape, and reached depths of 60-80 feet into the earth, serving as a perennial source of potable groundwater.

These water structures change their names across India's cultural landscape—bavdi in Hindi-speaking regions, vaav in Gujarat and Marwar's desert lands, kalyani or pushkarani in Kannada-speaking territories, and barav in Maharashtra.

Ancient water management

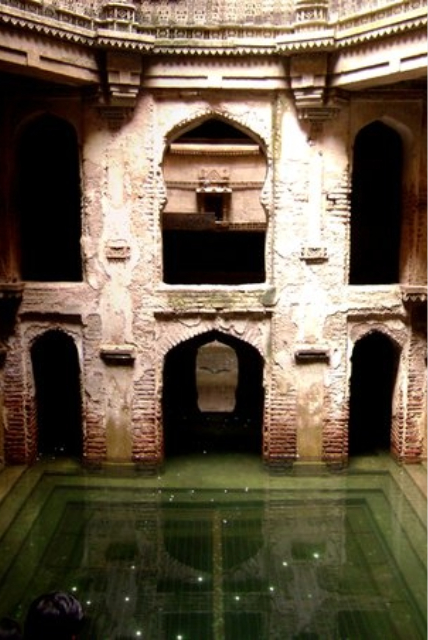

A dome (gumbad) adorned with intricate carvings and a parapet gives way to a water reservoir that seems to emerge from the depths of the earth. Multi-layered with stories that run deep and columns that create a hypnotic illusion of windows within windows, these structures appear as if the building had been uprooted and turned upside-down, tucked comfortably inside the earth. They break away from architectural archetypes in an attempt to create a subversion of design penetrating the very ground beneath our feet. The temperature drops dramatically as you descend the steps. The air grows heavy with moisture, its traces visible in the moss-ridden brick and mortar—a microclimate preserved within these ancient walls that tells the story of Gujarat's enduring relationship with water conservation.

Riyaz Tayyibji, an acclaimed Ahmedabad-based architect, deconstructs their structure. He says that they emerge as linear buildings exemplifying a remarkable architecture of subtraction. “Each structure is carved downward into the earth rather than built skyward. Its form begins with a square, circular, or octagonal dug well that becomes accessible through stairs descending purposefully into the ground. The uppermost landing features a shaded roof supported by columns, creating the first threshold between scorching sun and cool sanctuary,” says Tayyibji.

These architectural marvels are typically constructed from locally available materials, primarily sandstone or limestone. The natural porosity of these rocks serves a crucial function, allowing water to permeate the stone and helping maintain the well's water level.

As one descends, each subsequent flight of stairs leads to another landing adorned with an open structure—elegant pavilions, rhythmic colonnades, or intimate porches—until finally reaching the life-giving well at the lowest depth. These landing pavilions create a cascading architectural poetry, where each level's columned platform becomes the sheltering roof for the space below, forming a nested sequence of spaces that grow more intimate with depth.

The vertical walls surrounding the well often display intricate artistry—decorative brackets, niches, and sculpted ornamentation that transform functional infrastructure into a cultural artefact. Although some stepwells incorporated shrines and religious imagery within their structures, they largely remained secular, serving communities across religious and social boundaries.

These architectural marvels are typically constructed from locally available materials, primarily sandstone or limestone. The natural porosity of these rocks serves a crucial function, allowing water to permeate the stone and helping maintain the well's water level. Traces of other porous materials such as lime mortar can also be observed throughout these structures, further facilitating water management.

Also read: Bengaluru is fated to run out of water. When will the crisis hit?

The engineering wisdom

"Stepwells were and still are a unique spatial expression and often served as an extension of the domestic habitat, in that the people could spend the hot days of the summer months in the cool environs on the platforms, stairs and steps, galleries and balconies of the stepwells, especially in the hot and arid regions of Western India, such as Rajasthan and Gujarat, and also central and Northern India," says Jutta Jain-Neubauer. Jain-Neubaur, an art historian specialising in water architecture in ancient and medieval India, explains how stepwells represent a form of ‘embedded knowledge’ about sustainable water management that remains relevant to contemporary water challenges.

She says the ancient knowledge of the “so-called water-diviners was imperative in determining the location of a well or stepwell—it could not have been built anywhere, but had to tap the underground source of water.” “Therefore, the knowledge of the aquifers and geological surroundings where water might be found and accumulated was needed. Additionally, hydrological knowledge of underground constructions was necessary to prevent water seepage during construction and to determine the quality of water, which remains relevant to this day.” According to the scholar, stepwells, being underground monuments, required a very specific and high-quality technical knowledge of digging into the earth, as well as constructions to ward off the pressure of the side-walls when they were deeper underground. “Perhaps it is millennia-old experience and knowledge that manifested itself in the construction of stepwells.”

Stepwells, being underground monuments, required a very specific and high-quality technical knowledge of digging into the earth, as well as constructions to ward off the pressure of the side-walls when they were deeper underground.

A consistent pattern emerges in the relationship between depressions where water collects to form small lakes (talav) or ponds (talavadi) and the higher ground or mounds (tekro) inhabited by communities. This fundamental dialogue between water and settlement has profoundly shaped the character of built environments across generations. Where the talav still cradles water, the associated wells flourish with life; where talavs have been filled or their sources obstructed, the wells have withered to dust, revealing an intricate, almost symbiotic relationship between surface waters and the groundwater that feeds stepwells.

The present crisis

Ironically, groundwater supply shortages emerge as the most severe risk confronting the Indian subcontinent over the next two years (2025-2027), according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). To add to the mix, India is the world's largest consumer of groundwater.

A lone standing board at the crossroads of the Tarsali area in Vadodara reads 'Vavnagri'—the city of stepwells. However, only overgrown foliage and ruins of stone remain to speak of that tall claim. In the Gorwa area of, another stepwell lies buried under heaps of garbage, having devolved into a ground for open defecation. In the proximity of other stepwells, garbage from residential buildings is often dumped into these ancient structures.This remains the present-day narrative for many stepwells that have fallen off the map, their historical significance obscured by neglect.

Yet, some have been taken under the wings of the Gujarat Archaeology Department, such as the Sevasi Vav in Vadodara, fondly called Vidhyadhar Vav by locals.

Also read: In Gurugram's rise, a cautionary tale about satellite cities and groundwater

Contemporary challenges and solutions

"Traditional water systems can manage only 3-5% of our current water demands in the modern urban context," says Tayyibji. "While we must learn from these traditional systems, they need to be reinterpreted. Ground quality has degraded significantly, contaminating water closer to the surface level. We must find feasible solutions for our contemporary needs. Stepwells work within a particular context, but that context has changed dramatically."

Environmentalist Rohit Prajapati from Vadodara echoes these concerns: "We're facing a water crisis because of excessive water mining and groundwater extraction. We need to examine our water balance sheet—how much we draw, versus how much is replenished. We're exploiting water resources while simultaneously preventing natural recharging by covering the earth with paver blocks and concrete. We need integrated systems of cleaning, water recharging, and most importantly, rationalising our water use."

Also lost is the watchful stewardship of community elders, who once observed their water systems with patient attention.

The path forward

"Traditional water structures have varying degrees of pollution, usage, and maintenance. However, even visibly neglected and polluted water sources still have high potential for restoration, sometimes with a water quality index that is comparable to municipal drinking water,” reads a water quality pilot study from 2020, focused on the Deccan Plateau. The pilot study observes that revitalisation efforts must consider both, initial restoration and maintenance; without the latter, stepwell structures can fall into neglect again.

“We also observe that a lack of education surrounding the significance of water structures—both functionally and culturally, combined with the short-term financial incentive of unsustainable farming practices—also represents a burden to sustainable revitalisation,” the authors of the pilot study add. Through conversations with local NGOs, leveraging cultural heritage value or tourism emerged as potential solutions to incentivise the restoration of stepwells.

Also read: 'What river?' How Mumbai's neglected Mithi punishes those that live on its banks

Spaces of community and culture

Beyond their engineering significance, stepwells served as vital community spaces. As Jain-Neubauer notes, "Stepwells were and still are a unique spatial expression and often served as an extension of the domestic habitat. People could spend hot summer days in the cool environs on platforms, stairs, galleries and balconies, especially in the hot and arid regions of Western India."

These structures played a significant role in shaping collective memory and identity within the communities they served. Local stories, folk songs, and oral traditions associated with stepwells became integral parts of said collective memory—the Song of Jasma Odan in Gujarat, local legends surrounding Wadhwan's stepwell in Surendranagar, Gujarat, and numerous poems and stories about chance meetings between strangers and travellers with girls at wells, all testified to their cultural significance.

Stepwells embody more than mere historical fascination; they represent embedded wisdom about sustainable water management, community gathering, and architectural innovation that speaks directly to contemporary challenges.

Kakoli Sen, a visual artist from Vadodara, Gujarat, whose work with stepwells spans over two decades of research and artistic practice, traces the fractured seams where these monumental structures have slipped from modern maps, meticulously stitching them back into our urban fabric. Through her eyes, one witnesses the haunting, gradual erasure of stepwells. She expresses how stepwells have faded to the fringes at a very slow pace.

Sen recalls how a local newspaper dubbed her 'vav premi' (lover of stepwells). In a concerted effort to create a discourse around stepwells, she conceptualised “Soul of a Vav”—an audio-visual installation of the stepwell narrating its story, she explains. The audience would sit on the steps like children sitting on their mother's laps and hear enraptured the tales of its glory.

Sen brings to life and reimagines stepwells as living, breathing narrators of their history. Her work excavates the vanishing legacy of stepwells; those architectural marvels are now relegated to forgotten corners of our collective consciousness.

Stepwells embody more than mere historical fascination; they represent embedded wisdom about sustainable water management, community gathering, and architectural innovation that speaks directly to contemporary challenges.

(Slider Image Credit: The Adalaj Stepwell, by Notnarayan, via Wikimedia Commons)

{{quiz}}

References

.png)