Home to 2,700 sewage treatment plants, the city could recycle more water than it uses

Editor’s note: The last two decades have been witness to the rapid and devastating march of unchecked urbanisation and climate change in India’s cities. Among the first victims of this change is freshwater and access to it—from rivers which sustained local ecosystems, to lakes and groundwater which quenched the thirst of residents. In this series, the Good Food Movement examines the everyday realities of neglect and pollution. It documents the vanishing and revival of water bodies, and community action that made a difference.

“We’re flushing money down the commode!”

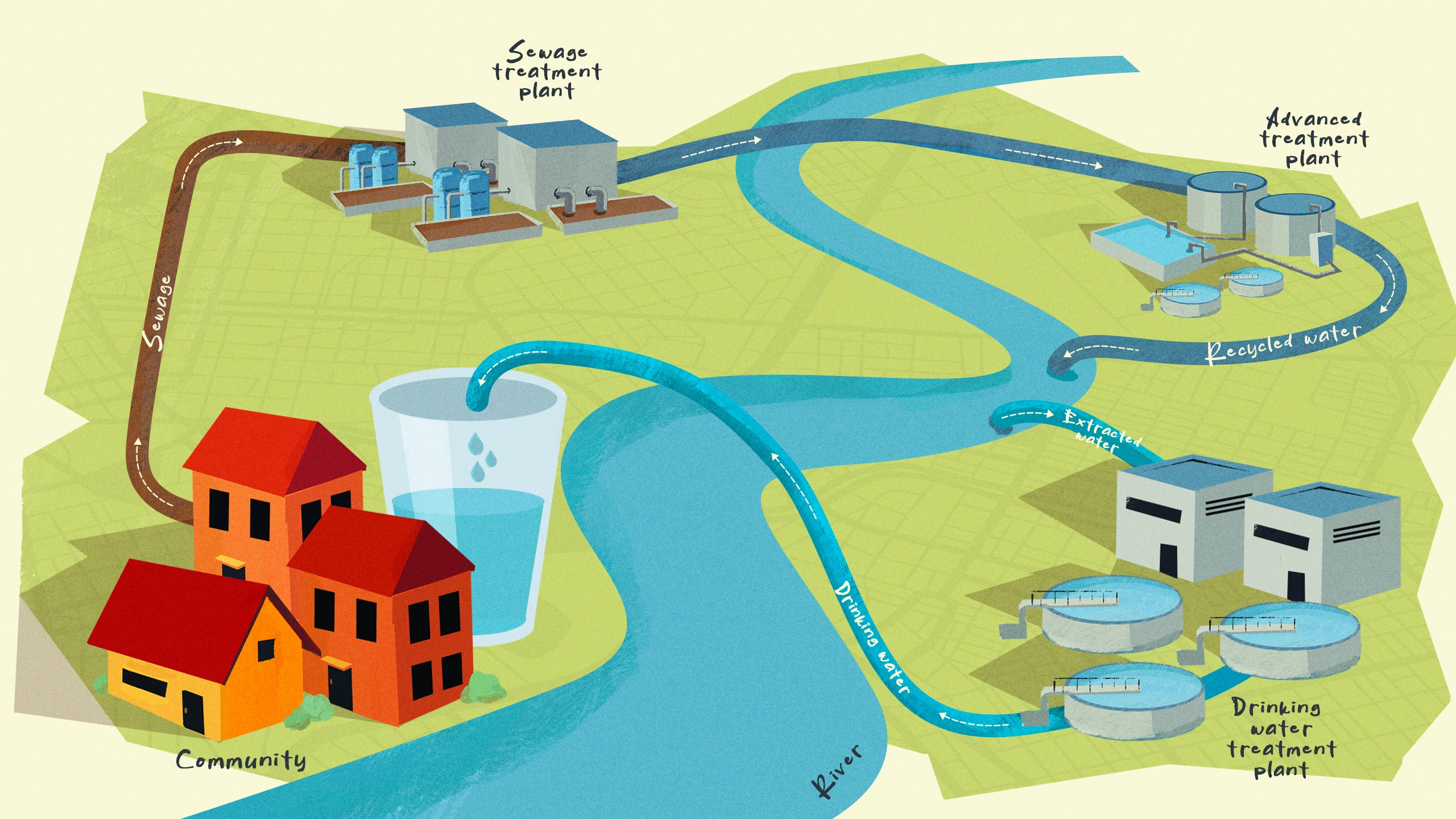

When Professor R. Rajagopalan exclaims this, he neatly captures both the value of water, as well as what we lose by simply flushing it away and draining it into lakes. Recycling water, treating it via Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs), and re-using it in our daily lives is not merely a question of water sustainability anymore. When run and used properly, STPs can enable climate resilience, recharge groundwater tables and blue, full lakes, as well as save a lot of money.

Rajagopalan, a former professor at the Institute of Rural Management (IRMA), believes this fact—and lives it. He has been the Chairman of the massive L&T South City Apartment complex in Bengaluru—a residential space comprising 1998 flats with over 7,000 residents—for over a decade. “We get our water supply from three main sources,” he explains. “Our onsite borewells, public water supply delivered by the Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB), and water tankers. At one point, we had 60 tankers coming every day to fulfill our needs. Who wants to hunt for so many tankers? Forget Bengaluru, it's too much for me to manage.” Tankers also don’t come cheap; Rajagoapan reveals that his apartment complex was spending as much as Rs 12 lakhs a month on them.

A city in crisis

2023 was declared a drought year by the Karnataka government. Rainfall in this year was inadequate in meeting the city’s water needs, so in the summer of 2024, Bengaluru made the national news for imposing restrictions on water usage for citizens. This led to loud protests across social media from residents of apartment complexes. More invisibly, it had steep consequences for the most vulnerable in the city.

In January 2025, the BWSSB and Indian Institute of Sciences (IISc) identified 80 wards that they understood to be most at risk to face a severe water crisis and scarcity in the summer. They recommended switching to Cauvery connections, with groundwater depleting at a faster rate.

They also note one crucial point in the face of this crisis: even as consumption of water has increased in the last few years, the amount of wastewater that is recycled in the city still remains low.

According to Water, Environment, Land and Livelihoods (WELL) Labs, a Bengaluru-based non-profit and research organisation, the factors that cause Bengaluru’s water crisis are interconnected. In their 2023 report, How Water Flows Through Bengaluru: Urban Water Balance Report, co-authors Rashmi Kulranjan, Shashank Palur and Muhil Nesi write: "With abundant rainfall and little room for recharge, wells run dry as drains overflow. Despite being allocated water from the Cauvery river, the expanding city, particularly the newer suburbs, has become increasingly dependent on a fast-depleting resource—groundwater.”

They also note one crucial point in the face of this crisis: even as consumption of water has increased in the last few years, the amount of wastewater that is recycled in the city still remains low.

Also read: In Gurugram’s rise, a cautionary tale about satellite cities and groundwater

A first-of-its-kind intervention

It was during this crisis, in April 2024, that Rajagopalan made his case to the residents of South City. He explained that investing in a retrofit project for reusing treated wastewater (TWW) from an installed STP for flushing toilets would benefit them financially and environmentally, of course—but more importantly, this would make them more water-resilient. Stronger in the face of future crises.

“The timing of our project was important. If water is not available in a high-rise building, it will cause hell. When the Bengaluru water crisis came in 2024, the only way we could ration water in South City was to stop water supply in one bathroom in each flat. Sheer irritation was introduced,” he says, with a touch of humour. “People are willing to throw away money to buy more tankers, but you can not over-consume water when the city is suffering. What we found was that out of 12 lakh litres that we used every day, between 3-4 lakh litres was for flushing. With the BWSSB water supply never being sufficient, we had to buy tankers just for flushing. It was too expensive. So people were eager to get the retrofit for treated water use implemented.”

South City made a commitment to BWSSB: they will execute the treated water project expeditiously, if their sanitary charges can be reduced in proportion to their extent of treated water reuse. Currently, houses in a domestic highrise pay a minimum of Rs 100 or 25% of their water bill per month as sanitary charge if they get their water from BWSSB, or a flat amount of Rs 100 if they get it from borewells.

“We retrofitted 1630 apartments in 18 high-rise towers. Within a matter of 6 months, between March and September of 2024, we started saving 3.5 lakh litres of fresh water a day, and Rs 9 lakh per month on freshwater purchase through tankers,” Rajagopalan says. “People realised that they were literally flushing money down the toilet, because each house was using one tanker a month—just to flush! After installing the STP, tankers have been reduced by about 10%. In fact, after accounting for the usage of this treated water in our housing complex, we still have enough to let out into a neighbourhood lake.”

This makes South City a pioneer—the first apartment in Bengaluru to strike an MOU with the State Pollution Control Board and Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) to let treated water revive a lake. “We also supply our treated water to a large public park. Our retrofit project is living proof that policy support could trigger an environment-friendly private effort to conserve water,” Rajagopalan adds.

A problem of abundance

In 2016, the BWSSB passed a mandate that required every apartment complex larger than 20 units to have their own STP and reuse all their treated water, but was met with resistance. In 2023, the mandate was amended; it stipulated that residential and commercial buildings above a certain area should install on-site decentralised sewage treatment plants (STPs).

WELL Labs reports that Bengaluru generates enough wastewater a day to fill over 750 Olympic-size swimming pools. This is more than the amount of water it draws from the ground or the Cauvery river. Critically, the city’s water supply and sewage system does not cover the rapidly growing suburbs with higher population densities.

The city now has the largest number of decentralised STPs globally—about 2,700, which can treat over 615 million litres of sewage every day. Beijing has 2000 such STPs, San Francisco has 50, and New York only has 30 plants. But many of Bengaluru’s plants are being under-utilised: many are defective, don’t meet specifications, and the apartments may remain unaware of the problems with the plant.

But there is one more problem with treating wastewater in apartments. About 30 kms across South City, an STP was installed for the residents in Century Saras in Yelahanka right when the complex was being constructed. However, even with 128 flats and over 350 residents, this society never had BWSSB connections, still doesn’t, and does not want them in the future.

According to Suresh Pai, Vice President of the Century Saras’ Owners Association, “We don’t have any BWSSB water pipes here and we are not connected to the sewage lines. The government is always 10 years behind development, but between rainwater harvesting, water saving measures, and our STP, we meet our demands internally.”

He explains the hesitation in getting a connection now, which will only increase costs. “We save about 20,000 liters of water per day because of the STP. We use most of the treated water in our common areas, and have also given it away to a nearby construction site, but now we have to let some go into the stormwater drains because no one is ready to take our excess water—even though we’re ready to give it for free!”

Pai points out a well known challenge in the STP ecosystem: he mentions the quality control that the building does once a month on its treated water, assuring that it meets every criteria. Yet, in the absence of without support from the BWSSB, there is no market for treated water. “Tanker operators were not ready to take the water, because they can’t use the same tanker for fresh water and treated water. And there were not enough buyers for treated water.”

Local authorities, too, are cognizant of how much treated wastewater is going to waste. Of the wastewater treated by both decentralised and BWSSB-held STPs every day, nearly 720 million litres remain unused. Treated wastewater can replace freshwater in many non-potable uses. In fact, a 2023 report from the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), states that 80% of wastewater generated by urban India has the potential to be treated and reused for non-potable purposes like irrigation.

Local authorities, too, are cognizant of how much treated wastewater is going to waste. Of the wastewater treated by both decentralised and BWSSB-held STPs every day, nearly 720 million litres remain unused.

That’s not all. Treated wastewater can even recharge lakes and aquifers, or groundwater levels. Efforts of this nature and scale are regional, and each state actually sets its own policies and standards on mandated usage of treated wastewater, where it can be used, and so on. The Karnataka government lists wetland restoration, river augmentation, and environmental recreation as potential areas for TWW reuse. As of today, the BWSSB is looking to recharge about 40 lakes within Bengaluru with treated water.

As detailed in a Mongabay India report, the state experimented with this in 2018, when it filled 137 water tanks in Kolar, a drought-prone region, with TWW from Bengaluru. In a recent assessment, it was found that the groundwater levels in the Kolar tank have now increased by 73% and the number of water bodies increased by 5 times. The number of trees shot up and even cropping land increased. It was an immensely successful endeavour.

Yet, having too much treated wastewater on one’s hands remains an ongoing issue.

Also read: Bengaluru is fated to run out of water. When will the crisis hit?

Moving away from the individual to the community

Apartments couldn’t always sell their treated wastewater. In fact, it was only last year that the Karnataka government allowed apartment complexes to sell a maximum of 50% of their treated water. This one move created an entire wastewater market that could potentially meet 26% of the city’s needs. According to WELLS Lab, treated wastewater is being sold at around Rs 10-80/kL–compare this to the price of tankwater, which can go as high as Rs 200/kL.

Shashank Palur, Senior Hydrologist at WELL Labs says, “The wastewater ecosystem hasn’t scaled. While apartment complexes comply with the 2023 mandate, challenges with the quality of treated wastewater remain, and more importantly, the lack of places to send the excess water to. Most apartments can use portions of their treated water for green or common areas, and some can use them for flushing, but the remainder is let out into the drains. The BWSSB has set up a website where organisations can buy treated water from their STPs, but it has not caught on.”

According to WELLS Lab, treated wastewater is being sold at around Rs 10-80/kL–compare this to the price of tankwater, which can go as high as Rs 200/kL.

The private sector has invested in setting up treatment plants, too. Sachin S.V., Senior Engineer Environment at Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL), shares that BEL put in place a 10 million litre STP along the Doddabommasandra Lake in 2018; since then, the state government has recharged and replenished the 300-year-old lake with the treated water from the STP. “Through our CSR initiatives, BEL is also in charge of maintaining this STP for the next 20 years. With the rising population, STPs are the best option to reclaim 80% of water that is going to waste.”

As Bengaluru moves forward, Palur thinks all these learnings and success stories can demonstrate a more efficient approach to the city’s water with the right mix and scale of STPs, in a more sustainable fashion.

He says, “The BWSSB is building more STPs with better treatment capacities; however, these are towards the outskirts of the city, due to a lack of space. Topographically, (being) at a lower elevation, this makes sense for treatment–but not reuse within the city,”

When it comes to apartment STPs, Palur argues that the approach should shift away from individual apartments to being community-oriented. “Piped network for supplying treated water can be explored, as it makes better economical sense in the long term. The larger city-wide trunk line for treated water supply needs to be owned by BWSSB, but the initial efforts can be taken up by the community, and (helped by) incentives by the BWSSB. We are working on that right now, coming up with models and vetting solutions to see how this can work out.”

Edited by Neerja Deodhar and Anushka Mukherjee

Produced by Nevin Thomas and Neerja Deodhar

Also read: Recycled water helps meet India’s cleaning needs. But can it quench our thirst?

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

.png)