Procurement and milling delays force them to burn their stubble

In October 2023, thousands of farmers in Punjab protested by holding a chakka jam–blocking major roads–in the cities of Sangrur, Moga, Phagwara, and Batala. The protests, organised by the Bharatiya Kisan Union, were in response to significant delays in paddy procurement and fines issued to farmers for stubble burning. Farmers found guilty of stubble burning owe Rs.10.55 lakhs in fine–but this isn’t all. The Punjab police has lodged 870 FIRs and marked red entries in the revenue records of 394 farmers.

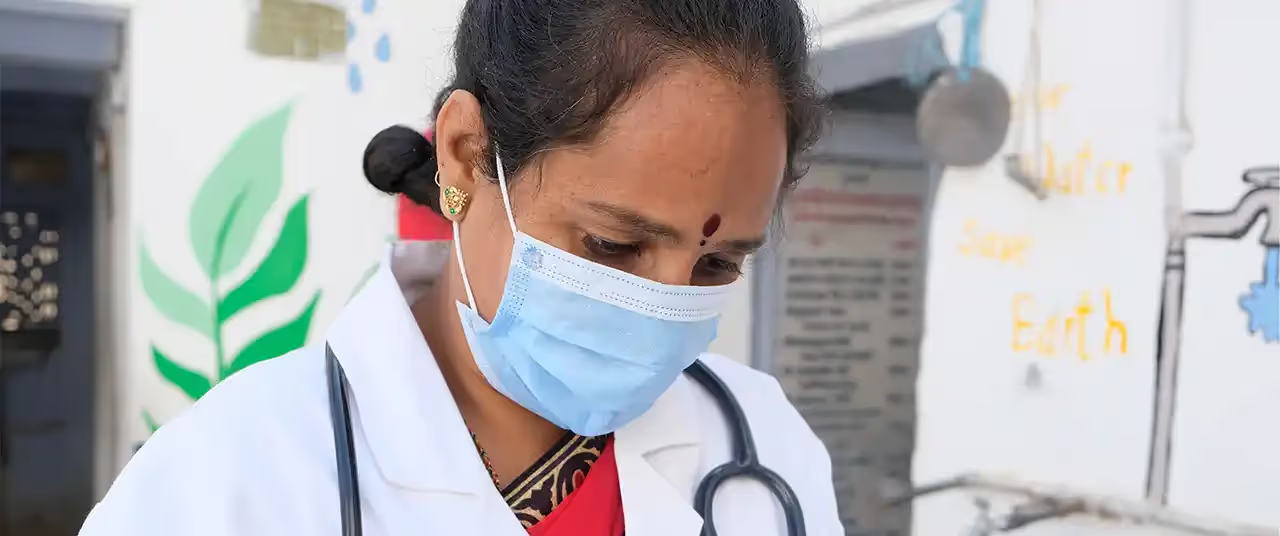

The protests came right after a summon by the Supreme Court. In October, as the winter grew chillier in the north, the air quality in Delhi sunk to lethal levels. The AQI averaged at 234 in October, and it would jump another hundred points in the next month. The state and central government ramped up their efforts to control pollution and improve air quality–and in the same month, the Supreme Court criticised Punjab’s role in Delhi's pollution, summoning both Punjab and Haryana’s state officers to court. The states responded by immediately fining farmers.

But how much does stubble burning in Punjab contribute to Delhi’s worsening air quality?

Air pollution, broken down

Air pollution in Delhi and the NCR is driven by multiple factors, particularly human activities in densely populated areas. Key contributors include:

- Vehicular emissions

- Industrial pollution

- Dust from construction and demolition

- Road and open-area dust

- Open biomass and municipal solid waste burning

- Fires in landfills

Delhi’s topographic location in the Indo-Gangetic plains also makes the situation worse.

During the post-monsoon and winter months, cooler temperatures, lower mixing heights, inversion conditions, and stagnant winds trap pollutants, leading to higher pollution levels in the region. The problem is worsened by episodic events like stubble burning, firecrackers, firewood burning in the nights, etc.

Every year, the state as well as private agencies conduct source apportionment studies that ascertain exactly where Delhi’s pollutants come from–and consequently, what percentage of pollution is caused by which source. A recent report by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) has found that local pollution sources, not farm fires, were the most significant cause for Delhi's worsening air quality ahead of Diwali this year. The city’s air quality dropped from "poor" to "very poor" on the air quality index, despite stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana contributing only 4.4% to the pollution, according to the analysis.

Still, Punjab’s farmers are repeatedly blamed for stubble burning–even when there are other major crises plaguing them.

Paddy procurement crisis

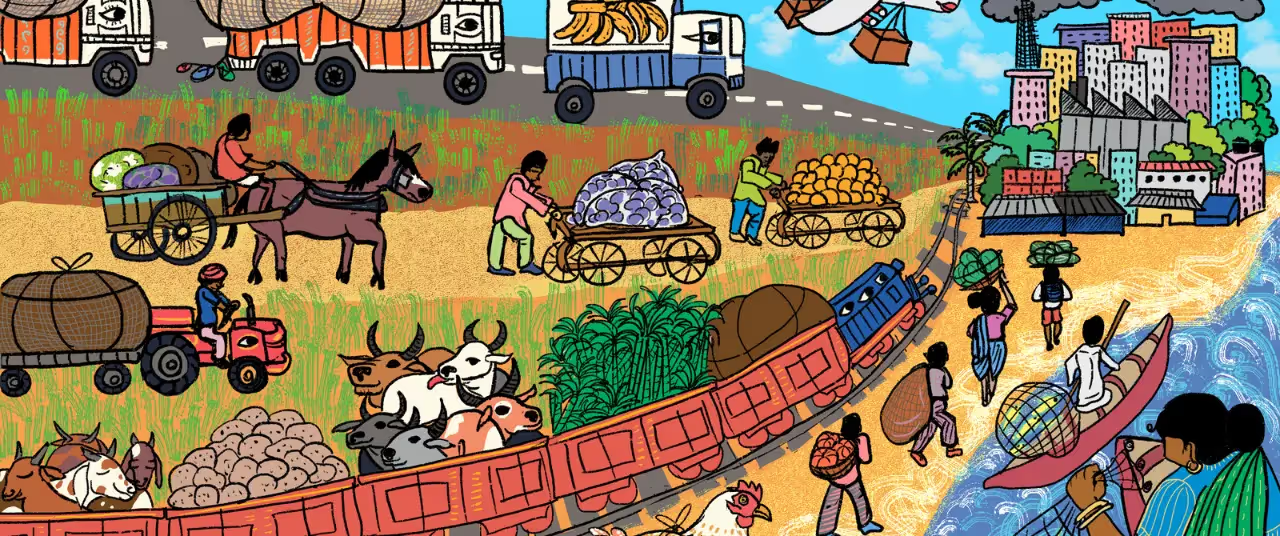

One of these is the massive delay in the procurement of paddy grown by Punjab’s farmers. Despite Punjab achieving its highest-ever rice cultivation area in 2024, paddy procurement is at its lowest in five years. The entire paddy supply chain–from cultivation to its delivery to Food Corporation of India (FCI) warehouses for the Public Distribution System–is under immense strain.

Each year, the Centre, in consultation with state governments and the FCI, sets paddy procurement targets before the kharif marketing season (October to September). For the 2024-25 season, the target was fixed at 185 lakh metric tonnes (LMT). However, as of 27 November, only 172.16 LMT had been procured, making it unlikely to meet the target. This shortfall has triggered ripple effects across the entire agricultural system.

The Punjab government, recognising the crisis, requested the central government to offload 20 lakh metric tonnes of milled rice to free up space in godowns. However, the request was not approved, leaving the godowns full and halting rice acceptance by millers.

Also read: Farmers demand a fair shake with minimum support prices

Millers’ rejection

Punjab’s 5,000 private millers are unwilling to accept paddy due to two key issues:

Storage woes: Millers are unsure how long they will need to store rice since government godowns are already full. Compounding the issue, millers still hold over 2 lakh tonnes of rice from the previous season. In 2023, the government accepted rice deliveries until 30 September, while the new paddy procurement season began on 1 October. However, millers completed deliveries only by 31 March. This overlap caused delays for farmers, who either waited for procurement or sold their paddy at Rs 150–200 below the Minimum Support Price (MSP) in a distress sale.

Outturn ratio: The rise of private hybrid paddy varieties has led to a lower Outturn Ratio (OTR)–the proportion of rice extracted from paddy during milling–than what the Food Corporation of India (FCI) requires. This shortfall makes processing these varieties unprofitable. This season, lower OTR is projected to cost millers an average loss of Rs 300 per quintal. Unless compensated for these losses, millers are reluctant to process the paddy.

The procurement bottleneck has significantly delayed harvesting the standing paddy crop. If the farmers harvest their paddy, they risk spoilage of procured paddy in storage–which can lead to a distress sale. Farmers also cannot transport their paddy to mandis, as they are already full. So, of the estimated 230 lakh metric tonnes of paddy, only 22% has been harvested so far, compared to 42% at this time in 2023. The remaining crop continues to deteriorate in the fields.

Paddy is usually harvested with a moisture content of 21–22% and sold at 17–18%. However, delays in harvesting have reduced moisture levels to 14–15%, lowering yields. Farmers expecting 30–32 quintals per acre are now losing 2–5 quintals per acre because of this moisture loss.

The shrinking window between the paddy harvest and the rabi sowing season is what forces farmers to resort to stubble burning. Without sufficient time for in-situ crop residue management, this practice becomes a necessity rather than a choice, further entangling Punjab’s farmers in a web of challenges.

“Earlier, farmers used to grow crops like potatoes and pulses between the rice and wheat seasons. However, the delay in paddy harvest has made this practice challenging,” says Sandeep Chachra, executive director of the NGO ActionAid.

Historically, there was a longer gap between crop cycles, and paddy was hand-cut much lower to the ground. There is substantial anecdotal evidence that the Punjab Agricultural University used to encourage farmers to burn paddy straw. It was also common for farmers to use the straw to feed their cattle. In fact, many old homes in villages had a special room near the cattle shed, known as the "toori wala kamra" (the paddy straw room). However, over time, the scale of paddy farming has expanded significantly, and the University’s previous recommendations have become problematic. Additionally, advancements in mechanisation and changes in seed types have led farmers to no longer use paddy straw to feed their cattle. Today, after a combine harvester leaves over a foot of straw in the field, it must be removed or mulched into the soil in order to plant wheat. The timing is critical, as there is only a window of about one to ten days for this to happen.

Economic vulnerability

Punjab's farming sector is already under economic strain, especially for small and marginal farmers, who, as of 2018, accounted for at least 65% of the state's 1.85 million farming families. Although Punjab ranks second in terms of average monthly income per agricultural household, its farmers are heavily burdened by debt. According to a study by Punjab Agricultural University, farmers in the state have borrowed over Rs 1,00,000 crore, with each farming household having owed an average of Rs 10 lakh to money lenders. Most of the farmers caught in this debt trap are small and marginal farmers, who make up 35 percent of the state's farming households. As it stands, farming has become an unprofitable occupation, and an estimated 12 percent of Punjab’s farmers have abandoned it altogether. A 2022 report by the OECD, which analyses agricultural policies in 54 countries to guide better policy making, revealed that Indian farmers have faced a more than 15% drop in revenue due to policies that suppress food prices.

Also read: On the deadly cost of farmer debts

Amandeep Sandhu, in his book ‘Panjab’, writes: “In 1971, the MSP for wheat was Rs 76 per quintal, and for paddy, Rs 21 per quintal. By 2015, these prices had risen to Rs 1,450 and Rs 1,400 per quintal respectively–a 19-fold and 67-fold increase. However, in the same period, salaries of government employees and professionals in sectors like education and corporate industries had risen by 120–1,000 times.”

Land inheritance laws that distribute land equally to heirs have further fragmented landholdings, pushing more farmers into the small and marginal category. The fragmentation has also institutionalised ‘theka’ farming, where farmers lease land instead of owning it, increasing their financial vulnerability.

Another critical issue is to do with groundwater–an invaluable resource for farmers. The Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Water Act (2009) aimed to align paddy planting with the monsoon season and water availability in the Bhakra Dam reservoir. Before the Act, groundwater levels were depleting by about one metre annually. Post-implementation, this rate slowed to three-fourths of a metre, saving approximately 20 centimetres of water annually.

Despite these gains, groundwater depletion remains a problem. In fact, paddy farming–which dominates Punjab’s agricultural area–demands and depletes massive amounts of groundwater. For years now, experts have recommended crop diversification in Punjab, for ecological sustainability and groundwater preservation. But this has proved difficult simply because paddy, a minimally labour intensive crop for farmers, brings the best returns–more than alternative crops like pulses, maize or potatoes. And thus, 80% of Punjab remains in the “red zone” for groundwater exploitation.

“Decreasing water levels are becoming a serious concern,” says Harpreet, a farmer from Jalandhar. The changing rainfall patterns are making things even more difficult. Our pumps can no longer extract water efficiently from underground sources because the groundwater levels have dropped significantly. To access water, we now have to dig much deeper, putting a strain on our finances."

Burning issues

Owing to these procurement delays and rejection of paddy from rice millers, the gap between paddy harvest and wheat sowing has now shrunk to just 7 to 10 days. This short window forces farmers to burn leftover paddy straw to clear fields quickly, contributing to severe air pollution. To track and monitor crop residue burning and estimate the area burned, ISRO developed standard protocols in consultation with key stakeholders, including the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), to ensure consistent assessment of fire incidents. According to the latest data, the number of paddy stubble burning incidents has dropped significantly, from 48,489 in 2022 to 9,655 in 2024. However, the area burned has increased from 17.81 lakh hectares in 2018 to 19 lakh hectares in 2023, out of a total paddy area of over 30 lakh hectares.

Also read: RTI Act: A powerful tool in fighting hunger

The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) has issued regular directives and advisories to various stakeholders (including 11 thermal power plants within 300 km of Delhi and the state governments of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh) to promote ex-situ stubble management by creating a strong supply chain to use straw effectively and curb stubble burning. While converting surplus residue into energy feedstock can boost farmers’ income, Gurleen Singh, a farmer from Rajpura, pointed out that only a few companies are buying stubble. Initially, they offered good rates, but pricing has now become uncertain and depends on how the stubble will be used.

“Transporting and storing bulky straw adds significant costs, making it less economically viable,” says Chachra. He emphasised the need for strong organisational systems to ensure farmers can sell or supply straw on time.

In 2018, the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare (MoA&FW) launched a scheme to subsidise crop residue management (CRM) machinery for individual farmers and set up custom hiring centres (CHCs) in Punjab for in-situ paddy straw management. However, according to Ramandeep Singh Mann, an independent food and agriculture analyst, “Farmers often face significant delays, sometimes up to a month, in receiving machines from the CHCs. As a result, many are left with no choice but to resort to stubble burning.”

By 2023, around 1.3 lakh subsidised machines had been distributed, and 163 CHCs established, according to Jagdish Singh, the state nodal officer for CRM.

“Even with subsidies, CRM machines remain expensive for small and marginal farmers. For example, a Happy Seeder costs around Rs 1.5–2 lakh, making it unaffordable without substantial financial aid,” says Chachra. Many smallholders struggle to access these machines, leading to uneven adoption. He also highlighted that many of these machines need skilled operators and work best with dry stubble, becoming far less efficient in high-moisture conditions. Adding to the challenge, CRM machines run on diesel, and rising fuel prices make them even costlier to operate.

Tackling crop residue burning in Punjab requires more than one solution. “We need a multi-pronged approach,” Chachra explains. “We need to have a stronger push towards promoting crop diversification in the state and shift away from paddy. This calls for encouraging farmers to adopt low-water, short-duration crops like maize, pulses, oilseeds, and millets as alternatives to paddy.”

To support this shift, the Punjab government promised a minimum support price (MSP) for ‘moong’ to incentivise diversification. “While farmers responded by cultivating moong, they are now struggling to sell their produce,” says Sandeep Singh, an independent journalist.

Punjab's farming sector faces a complex web of challenges, from the procurement crisis to the economic pressures on small farmers. While stubble burning is often blamed for air pollution, it's only one piece of a larger puzzle. Without comprehensive solutions, Punjab’s farmers will continue to struggle, with consequences that extend far beyond the fields.

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References