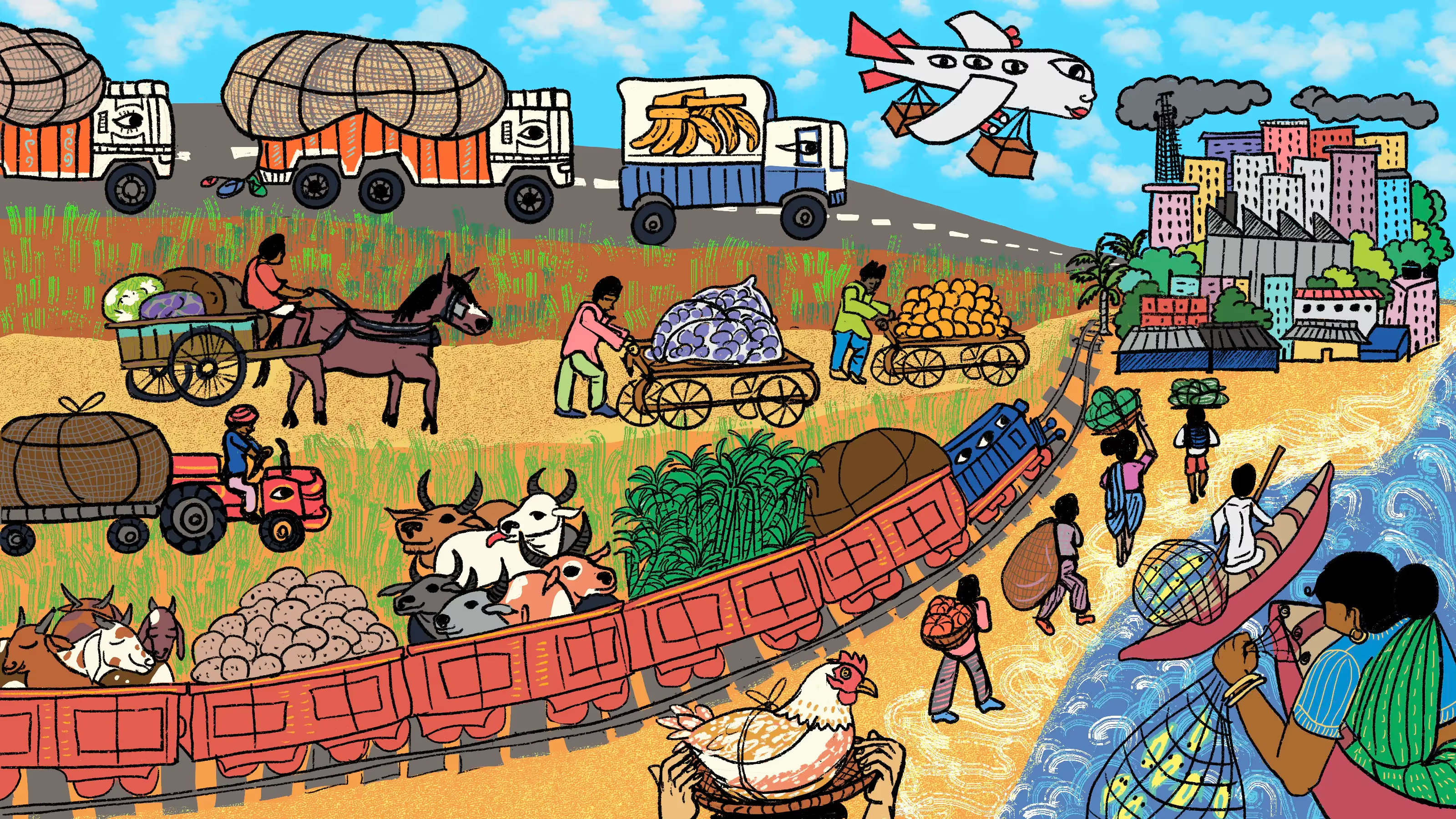

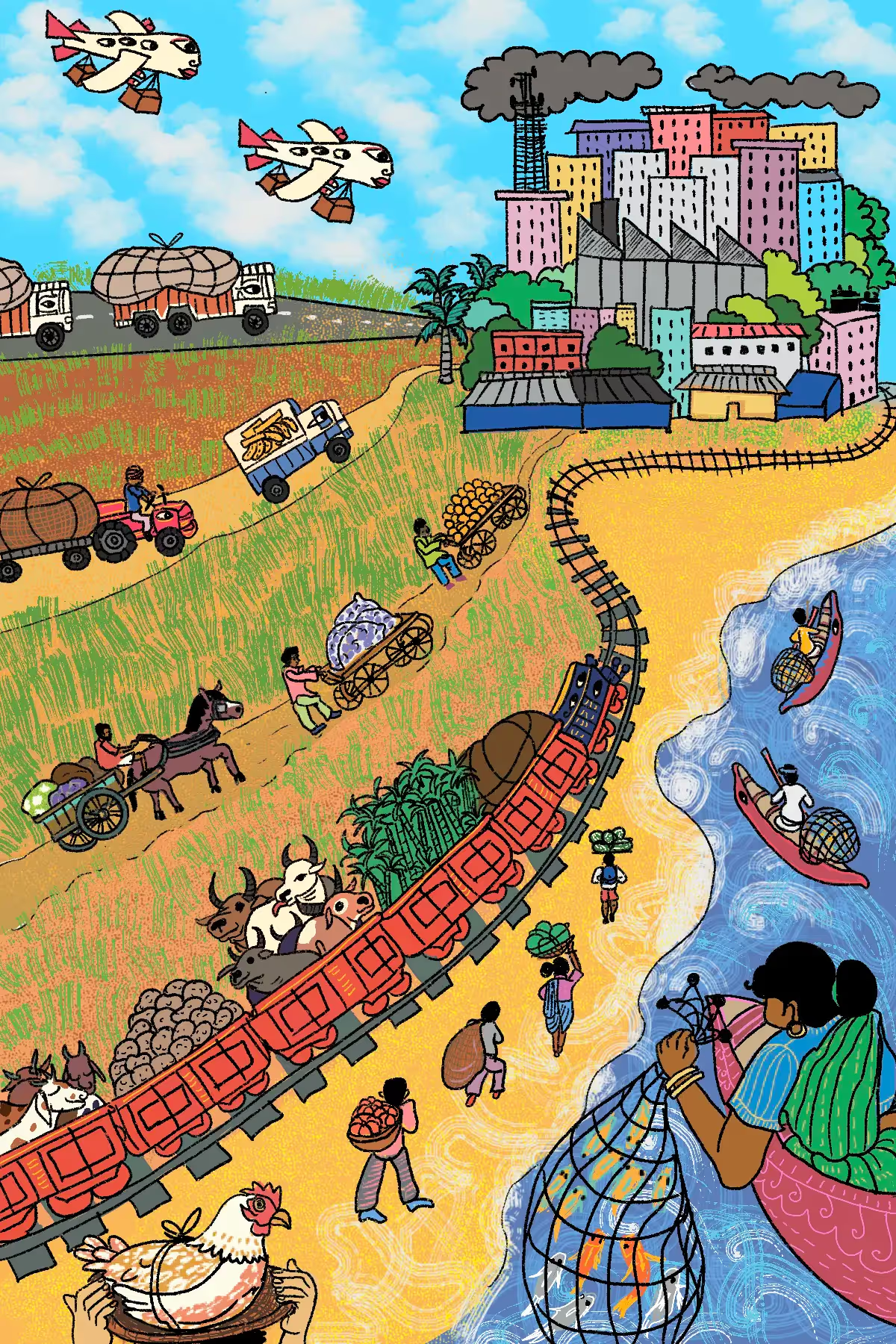

Behind well-fed metropolises are street vendors, produce that travels many kilometres, and fragmented supply chains

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

Every morning, as India’s cities slowly come to life, crates of vegetables and fruits—some harvested just hours earlier in fields nearby—are unloaded in wholesale as well as Agricultural Produce Market Committee APMC (APMC) markets. Street vendors ready their carts for the day’s trade, small eateries fire up their stoves to serve the first wave of officegoers, and shelves at local grocery stores and supermarkets are stocked in preparation for the day ahead. Day after day, this quiet choreography sustains the vast and often invisible system that keeps cities fed.

But as India’s metropolises expand, these well-rehearsed routines are being reshaped. In this column, I take a closer look at what it means to feed a city fairly and sustainably in such a changing landscape.

How food gets to the city

Across the country, food reaches urban centres through networks that span vast and varied geographies. These supply chains link remote farms, peri-urban fields, fisheries, livestock holdings, and processing units to urban markets, grocers, eateries, and homes. Food in India travels shorter distances on average, compared to large industrial countries like the US. Food reaching American cities travels over 1,600 km per metric tonne; at around 480 km per metric tonne, food supply to Indian cities averages less than a third of that, owing to more regionally embedded production systems.

Chennai offers an insightful example. In 2020, as COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted lives and economies, the city’s food system came under sudden strain. The closure of Koyambedu market, one of Asia’s largest wholesale hubs and a vital artery for fresh produce, raised urgent questions: how does a metropolis like Chennai get its food?

The Urban Design Collective’s project, Who Feeds Chennai? emerged in response. The initiative traced the movement of vegetables, among other staples, and found that the city’s fresh produce was largely sourced from its peripheries as well as adjoining districts. Another study conducted by IIT Madras found that traders based in Koyambedu, many of whom are unionised, handle the logistics of transport. Smaller farmers unaffiliated with middlemen sometimes travel up to 200 km to reach the city. Certain vegetables were even found to travel over 1,000 km from northern India.

For most other cities, such mapping remains absent, due in part to the informal and fragmented nature of supply chains and the lack of institutional attention to urban food planning.

Staple grains were found to reach Chennai from further afield. While some rice is sourced from Tamil Nadu’s delta districts, much of it arrives from states like Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, Assam, and West Bengal, with brokers linking producers and Chennai-based millers. Wheat is mainly procured from Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh through similar channels. Pulses come from a mix of local sources and distant states such as Delhi and Haryana, as well as from international suppliers including the US, Canada, Australia, and Mozambique.

The city’s meat supply is more decentralised. Poultry, Chennai’s most consumed meat, is brought in from Tamil Nadu and nearby southern states, often through vertically integrated systems where companies provide chicks, equipment, and market access to local growers. Mutton, the second most popular meat, is transported over 2,000 km from states like Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra, while beef typically comes from Kerala. Fish arrives not only from the Coromandel Coast but also from other coastal regions, thanks to improvements in cold storage infrastructure.

Projects like Who Feeds Chennai? offer a rare glimpse into how food reaches an Indian city. For most other cities, such mapping remains absent, due in part to the informal and fragmented nature of supply chains and the lack of institutional attention to urban food planning.

Around the world, city governments are increasingly recognising the importance of understanding and managing how food circulates through urban systems. A leading example is the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, a global agreement signed by over 250 cities such as Milan, Nairobi, Rio de Janeiro, Seoul, Toronto, New York City, Dakar, Melbourne, and Amsterdam. Launched in 2015, the pact has supported initiatives worldwide to map food flows, strengthen urban–rural linkages, reduce waste, and improve access to nutritious food through public procurement and community-based programs. The Indian cities of Bhopal, Indore, Jammu, Panaji, Pune, Rourkela, Sagar, and Ujjain are also signatories. However, there is little publicly available information on whether these cities have undertaken detailed mapping of their food systems.

Also read: The circular bioeconomy movement can change how we see waste

The changing face of peri-urban India

As urban centres expand, they draw food, water, labour, and land from their margins, reshaping both agricultural production and everyday life. In the National Capital Region, rising urban demand has led to significant changes in land use in peri-urban regions, especially in Haryana. Farmers are increasingly turning to high-value crops like fruits and vegetables, aided by state support for polyhouse cultivation, horticulture promotion, and improved market access. These shifts are not only transforming cropping patterns but also strengthening local supply chains that feed the growing urban population.

However, risks remain: many smallholders face insecure tenure, erratic access to water, and volatile market conditions that limit long-term investment. As real estate interests encroach and cultivation becomes more marginal, benefits from intensified production are unevenly shared. Without more inclusive governance and safeguards for farming livelihoods, these shifts may deepen existing inequalities.

What enables economic survival in the short term may be contributing to long-term health and ecological decline.

In Bengaluru’s peripheries as well, food production has shifted away from traditional crops like millets and pulses towards high-value and high input-demanding crops like baby corn, mulberry, cattle fodder, as well as lawn grass. In particular, the rise of lawn grass cultivation for Bengaluru’s landscaping industry exemplifies a form of extractive agriculture that is ecologically damaging, socially disconnected, and diverts land that could otherwise be used to grow local food crops.

As a result of the city’s struggles with fresh water supply, agriculture in Bengaluru’s southern periphery depends on untreated or partially treated wastewater for irrigation. This has allowed farmers to cultivate year-round, boosting incomes and enabling diversification. But this practice is not without pitfalls. Vegetables and milk from these zones have tested positive for heavy metals, and residents report high rates of waterborne and skin-related illnesses. What enables economic survival in the short term may be contributing to long-term health and ecological decline.

Also read: The promises—and perils—of Indian aquaculture

Informal food networks

Informal food networks, which take the form of streetside vendors and fish mongers, are central to how Indian cities eat. Unlike in many other parts of the world, large supermarket chains have failed to replace them, finding it hard to compete with the accessibility, affordability, and trust built into these local systems of provisioning. Though often overlooked in policy, informal food networks form a critical part of urban infrastructure, enabling both food access and livelihoods.

In cities like Mumbai, the informal food sector has been deeply shaped by the city’s history as an industrious port. Today, it is home to vibrant food networks that operate beyond the bounds of formal municipal governance but with a high level of coordination in how space and money are used.

Neighbourhoods like Dharavi, often reduced to shorthand for poverty or overcrowding, are also hubs of food processing, retail, and distribution. Dabbawalas, meanwhile, transport home-cooked lunches to offices across the city with remarkable precision, weaving through trains and traffic in one of the world’s most complex logistical systems.

Yet these systems remain precarious, and their workers vulnerable. Most vendors lack legal status, secure space, or access to basic infrastructure like clean water and waste disposal. Periodic evictions and restrictive regulations, often justified through concerns about hygiene or congestion, displace the very actors who make urban food access possible. These pressures are intensified by social hierarchies. Gender, caste, and migrant status influence who gets access to vending locations, how municipal authorities respond, and who bears the brunt of enforcement.

Kolkata offers a slightly different story. With over 3,00,000 vendors working across the city, street vending is just as widespread as other metropolitan cities, but more deeply tied to local politics. Over the years, hawkers have formed strong unions and built enduring ties with political parties. These relationships have allowed them not only to survive but also to resist eviction and, at times, gain influence over decision-making processes.

However, this visibility brings its own complications and power struggles. In many areas, clientelist politics now shape urban spaces wherein local leaders offer protection in exchange for votes. This means that basic services, rights, and fair treatment often depend on political loyalty rather than formal legal protection.

In 2014, India passed the Street Vendors Act, a national law aimed at recognising and protecting the rights of street vendors. It called for detailed surveys to register vendors, the creation of designated vending zones, and restrictions on evictions without due process. The law was intended to bring dignity and security to informal food work. But more than a decade later, implementation remains limited. Other kinds of food workers such as food delivery staff and domestic cooks also remain on the margins of labour protection, often navigating long hours, low pay, and few avenues for redress.

Also read: Can India’s traditional knowledge future-proof its food system?

Planning for future-proof systems

As of 2025, urban food policy in India remains inconsistently implemented and disproportionately influenced by upper and middle-class interests, with little recognition of the informal actors who play a central role in enabling food access. A more inclusive approach must look beyond city centres and engage the wider geographies that feed them.

At a time when cities around the world increasingly turn to food imports to ensure food security—often adding to climate change—it is all the more important for India to draw on its rich biodiversity and traditional agricultural knowledge to meet urban food needs through domestic production.

Importantly, what becomes clear from examining India’s urban food landscape is that the path to improving it does not lie in replacing informal networks with privately led or corporate-controlled models. Rather, it lies in recognising that these networks of small traders, transporters, vendors, farmers, and millers form the foundation upon which urban food access depends. Far from being obsolete, they are resilient, adaptive, and deeply embedded in the country's social and economic life.

However, ensuring the rights and protections of those engaged in informal food work is not a call for deregulation, but for thoughtful, context-sensitive governance that values and safeguards these actors while addressing gaps in infrastructure, food safety regulation, transparency, and equity. Without such a framework, efforts to formalise or privatise the food economy risk excluding those who already deliver affordability and access to the majority of urban residents.

At a time when cities around the world increasingly turn to food imports to ensure food security—often adding to climate change—it is all the more important for India to draw on its rich biodiversity and traditional agricultural knowledge to meet urban food needs through domestic production. As a result of the country’s geographic and climatic diversity, a one-size-fits-all approach to urban food planning is unlikely to work. Policies must instead reflect regional specificities. Equally important is the need to curb corporate concentration in the food sector so that access to nutritious and affordable food is not limited to elites but extends to the working class. Encouraging the consumption of locally sourced foods through price incentives and public awareness can help align urban diets with regional food systems, supporting both sustainability and equity.

Artwork by Alia Sinha

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

.avif)