A holistic approach can lead to ecologically and socially sound solutions

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

Across India, it is not uncommon to find people relying on nature and its signs to determine the course of their own actions, from farmers predicting monsoon showers by observing the movement of ants, to herders navigating pasture routes based on the flowering patterns of local trees. Practices, skills, and insights that emerge from a community’s long-standing relationship with its environment, often passed down through generations, are referred to as traditional knowledge. The term is often used interchangeably with ‘Indigenous knowledge’, particularly in contexts where settler communities form the majority of the population, such as in the US or parts of Latin America. In these settings, Indigenous communities are typically recognised as the primary custodians of place-based knowledge systems.

However, in the Indian context, the distinction is less clear-cut. Much of what is termed traditional knowledge is held not only by constitutionally recognised Indigenous communities (Adivasis), but also by a wide range of rural and agrarian communities who have co-evolved with their local environments over centuries. Therefore, for the purpose of this column, I use the term ‘traditional knowledge’ as an inclusive umbrella that encompasses the diverse, place-based knowledge systems developed and sustained by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities over generations.

Traditional knowledge vs. science

In mainstream discourse, science typically refers to Western science—a system of knowledge production that privileges measurement, objectivity, and replicability. Built on principles of observation, experimentation, and statistical inference, it has yielded extraordinary insights into the natural world. It is, however, not the only way of knowing. Traditional knowledge, in contrast, emerges from long-term, lived engagement with particular landscapes. It is often transmitted orally, embedded in cultural rituals, and carried forward through everyday practices.

The two knowledge systems differ not only in method, but also in worldview. Western science often draws boundaries between the empirical and the spiritual, and the observer and the observed. Traditional knowledge tends to be holistic, integrating material, moral, and metaphysical understandings of the world. This divergence, shaped by colonial histories that privileged European systems of knowledge while actively suppressing others, has led to the devaluation and erosion of traditional knowledge in our societies over time.

Western science often draws boundaries between the empirical and the spiritual, and the observer and the observed. Traditional knowledge tends to be holistic, integrating material, moral, and metaphysical understandings of the world.

.avif)

Indian agriculture’s divergence from tradition

Agriculture in India has a 10,000-year-old history. Traditional knowledge systems related to food, farming, and land management have evolved over millennia, closely attuned to local ecologies and cultural practices. But despite this rich inheritance of place-based knowledge, Indian agriculture has steadily shifted away from these practices over the past two centuries. This departure is rooted in a complex web of historical, economic, and political forces, beginning with colonialism and continuing through post-Independence development policies.

Under British rule, Indian agriculture was reshaped to serve imperial interests. A system of exploitative land taxation, combined with the expansion of railways–and thus, access to markets– incentivised farmers to abandon biodiverse, subsistence-oriented polycultures like bajra, legumes and pulses in favour of monocultures of cash crops such as cotton, jute, indigo, and opium. In the second half of the 19th century, these shifts not only displaced food crops like millets, but also eroded the role of local ecological knowledge in shaping farming practices.

A second major transformation came with the Green Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. Introduced as a solution to food shortages, it promoted high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice, supported by state subsidies for fertilisers, pesticides, and irrigation. These new varieties produced nearly 3-4 times more yield than the traditional wheat and rice crops–at nearly 4 tonnes per hectare, over a shorter cycle. So, while this model boosted short-term productivity, it created dependence on chemical inputs, reduced crop diversity, and displaced traditional practices such as intercropping, seed saving, and organic fertilisation. As subsidies declined, smallholder farmers, who form the backbone of Indian agriculture, became increasingly burdened by debt and lacked access to affordable credit or secure land tenure.

Indian agriculture today finds itself at a critical juncture. It is shaped by decades of structural dependence, yet there is growing awareness of the ecological and nutritional costs of marginalising knowledge systems that were once central to its sustainability. The shift toward input-intensive staple crops has depleted soils, drained groundwater, and introduced harmful pesticide residues into the food supply, while displacing diverse, traditionally grown foods—making nutritious diets increasingly unaffordable and out of reach for much of the population. The current food system may deliver in quantity but falters in quality, with long-term consequences for both public health and ecological resilience.

Also read: The circular bioeconomy movement can change how we see waste

Can traditional wisdom inform innovation?

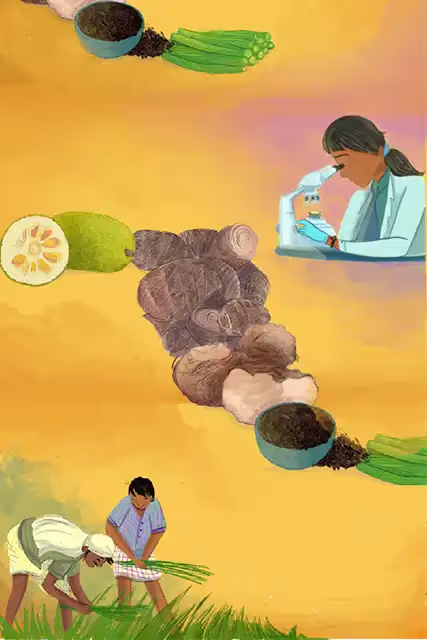

In recent years, a number of initiatives have shown that traditional knowledge and science need not exist in opposition. When approached with mutual respect and institutional support, they can work in tandem to create food systems that are both ecologically sound and socially just.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Future Smart Foods (FSF) project, launched in 2018, offers an important example. The initiative aims to diversify food systems by identifying and promoting underutilised crops that are rich in nutrients, climate-resilient, economically viable, and locally available. West Bengal was one of the regions included in the effort. The process involved mapping agrobiodiversity by drawing on both scientific literature and consultations with local communities, helping to identify a range of crops that had long been part of local food cultures but were largely absent from mainstream agricultural policy. Some foods identified as part of this exercise include black rice (kalonunia), swamp taro, elephant foot yam (ol kachu), jackfruit, and moringa pods (drumsticks). Low input requirements and a strong tolerance to climate fluctuations make these foods especially suitable for smallholder cultivation. Based on this local knowledge, the FSF initiative compiled a set of priority crops now recognised as vital for enhancing dietary diversity, supporting livelihoods, and building resilience.

Indian agriculture today finds itself at a critical juncture. It is shaped by decades of structural dependence, yet there is growing awareness of the ecological and nutritional costs of marginalising knowledge systems that were once central to its sustainability.

A similar convergence of science and traditional knowledge can be seen in the popularisation of millets. Long ignored in national food policy, these climate-smart grains are once again being recognised for their nutritional value and cultural significance. Scientific research has helped validate their role in addressing malnutrition and supporting sustainable agriculture, leading to renewed policy attention–for instance, including Ragi, or finger millet, in public distribution systems and school meal programmes. The recent declaration of 2023 as the International Year of Millets by the United Nations marked a turning point in how these traditional crops are being reframed through both scientific and policy lenses.

The case of Sikkim, India’s first fully organic state, is another example that demonstrates how traditional agri-food knowledge can be supported and scaled through institutional mechanisms. Many farmers in the region had long relied on low-input, ecologically attuned practices such as mulching with forest litter and crop residues, intercropping herbs like ginger and turmeric with staples such as buckwheat, beans, and tapioca to improve soil resilience, and using plant-based pest deterrents like neem and agave extracts. Farmers also practised nutrient cycling using forest biomass and employed terrace farming and local water diversion channels to prevent erosion and excessive run offs.

The state’s organic policy, implemented over more than a decade, built upon this foundation by phasing out chemical fertilisers and pesticides, introducing organic certification, and offering training and subsidies. The policy helped legitimise traditional practices within formal systems, creating new economic and social value for local knowledge. Agricultural scientists worked alongside farmer networks, helping to document and refine existing techniques, while the state facilitated access to organic markets.

However, the transition has not been without its challenges. Many farmers report declining yields for key crops like rice, maize, pulses, vegetables, and grains as pest management methods have proven insufficient and government support inconsistent. Organic inputs and training have not reached all cultivators, and critical data on pest attacks is lacking. And while the ‘organic’ label was expected to command higher prices, most farmers cannot access premium markets and remain dependent on middlemen. Certification costs are high, and commercial crops often receive policy preference over traditional food crops. Many also expressed dissatisfaction with the state's top-down approach, noting a lack of meaningful participation and democratic decision-making in the transition process.

Also read: The promises—and perils—of Indian aquaculture

Re-imagining what expertise looks like

A meaningful revival of traditional knowledge would require more than symbolic gestures or archival preservation. It would involve creating the conditions for these knowledge systems to be valued, practised, and allowed to evolve on their own terms; not as supplements to science, but as legitimate ways of understanding and engaging with the world.

At present, the integration of traditional knowledge into formal systems remains uneven and often tokenistic. Communication barriers, conceptual mismatches, and deep-seated power imbalances continue to limit meaningful collaboration. Knowledge is frequently extracted from communities, decontextualised, and repackaged within scientific or policy frameworks, with little regard for the social, spiritual, or ethical dimensions from which it originates.

Reviving traditional knowledge also means addressing the political and structural forces that have marginalised it. This includes recognising how colonial legacies, existing trade regimes, corporate hegemony, and gendered and caste-based power relations have shaped who gets to be seen as a knowledge holder. In many agroecological settings, women and caste-oppressed communities play a critical role in sustaining traditional knowledge. Yet their access to land, finance, and decision-making remains constrained. As Indian agriculture faces the twin challenges of feeding a growing population and adapting to climate change, it is essential to value the perspectives and knowledge that these communities bring to the table. Supporting their leadership should not be seen as an act of charity but a necessary step toward building a resilient, future-proof food system.

A meaningful revival must begin with the active involvement of knowledge holders in shaping research agendas, policies, and educational curriculums. Traditional knowledge should be documented through scientific but participatory methods that centre community voices and consent, rather than extractive research practices. Legal protections must be strengthened to prevent the appropriation or commercial exploitation of traditional knowledge without fair compensation. Public procurement programmes and agri-food subsidies should be restructured to support diverse, low-input farming systems rooted in local knowledge. And finally, a revival must be grounded in institutional humility—an openness to sharing authority and redefining what counts as expertise in the first place.

{{quiz}}

Illustration by: Kaushani Mufti

Explore other topics

References

.avif)

.png)