If the claims on the front mislead, and the nutrition panel at the back confuses, where does that leave us?

Imagine this: You’re a young adult at the supermarket, finally living on your own, trying to stock a kitchen for the very first time. You squint at the labels printed on the back of each product, but you can barely pronounce the words, let alone decipher their meaning. Tossing familiar items like bags of potato chips and ready-to-eat dumplings into your cart, you shrug and walk on towards the next shelf.

You are not alone in making these choices. The packaged foods industry in India was worth over $110 billion in 2023. This category includes household essentials like oil, salt, nuts and lentils; frozen foods; snacks like biscuits, noodles, and chips; dairy items like butter and cheese spreads—the list goes on. A recent survey by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) reveals a shift in Indian dietary habits. For both rural and urban households, the biggest share of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) now goes towards beverages, refreshments, and processed foods (notwithstanding informally packaged foods). The decade between 2011 to 2022 reflects a massive jump in these numbers—from 7.9% to 9.6% of the total MPCE in rural households; and from 8.9% to 10.6% of the total MPCE in urban ones.

Worryingly, the 2024-25 Economic Survey linked the rising consumption of ultra-processed foods (a Rs. 2,500 billion industry)—fuelled by misleading advertisements, celebrity endorsements—to nearly 32 non-communicable diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions.

If the front misleads and the back confuses, where does that leave the everyday eater?

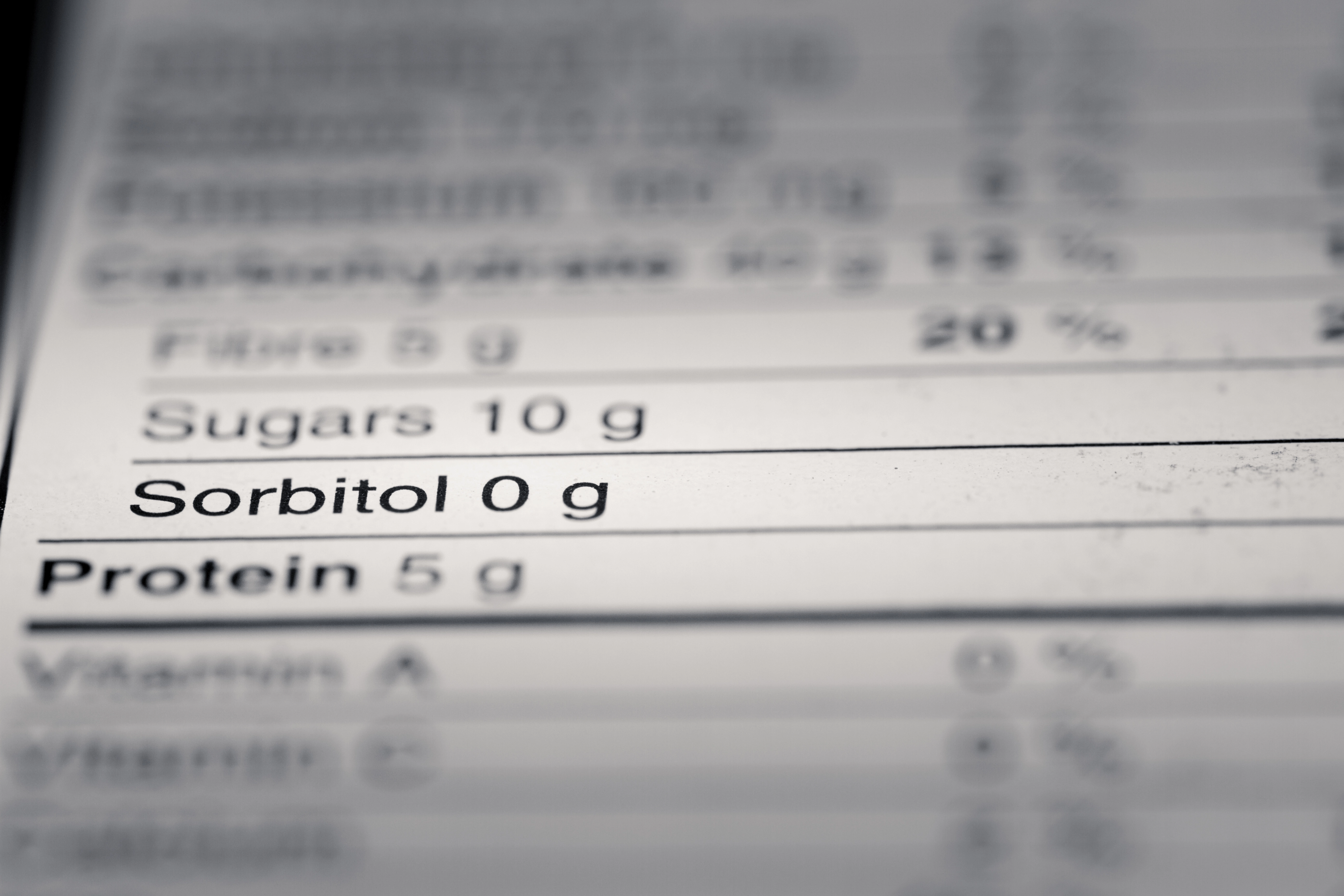

Even before this shift in consumption habits—but especially now—nutritional labels were meant to help consumers make informed choices when buying packaged foods, helping them reduce negative health outcomes. Yet, in today’s food economy, they double as advertising: bold claims like ‘low fat,’ ‘cholesterol free,’ or ‘natural’ dominate the front, even as the fine print tells another story. This dissonance has real consequences for customers. Most Indians struggle to read or trust labels—not because of indifference, but because they are crammed with jargon, printed in tiny fonts, and overshadowed by flashy promises of health and energy. If the front misleads and the back confuses, where does that leave the everyday eater?

A brief history of product labels in India

Before 2006, India’s food labelling was scattered. It had been regulated under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954, but labels were basic and largely focused on the name of the product, manufacturer details, a list of ingredients, net weight and expiry date. Any nutritional labelling beyond this was not mandatory.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) was set up in 2006 (yes, six decades after Independence!), and introduced the Food Safety and Standards (Packaging and Labelling) Regulations only in 2011. This was the first time that an exhaustive set of regulatory guidelines was released by a central authoritative body on food. They mandated a detailed nutritional facts panel (indicating amount of energy, protein, carbohydrates, sugar, and fat), and vegetarian/non-vegetarian symbols. The label was also required to mention ‘the amount of any other nutrient for which a health claim was made.’

In a 2013 survey conducted in New Delhi and Hyderabad, most consumers said taste, price, and brand name guided their choices.

In 2018, the FSSAI introduced the Food Safety and Standards (Advertising and Claims) Regulations, 2018. This revised version more strictly stipulated that foods must first meet specific nutrient thresholds for manufacturing companies to make claims like ‘zero cholesterol,’ ‘low-sugar’ or ‘gluten-free.’ For example, a ‘zero cholesterol’ or ‘cholesterol-free’ claim must be backed by the product containing no more than 5 mg cholesterol per 100 g (solids) or 100 ml (liquids).

Despite this, brands have had a history of coming under fire for routinely violating these regulations. Nutrition supplement powders for children promise to help them grow taller, stronger and sharper with not only negligible evidence to back up these claims, but counterintuitively, also containing additives like sugar in excess. Many packaged fruit juices also carry ‘natural’ or ‘no added sugar’ claims on the front, even though fruit juice syrups can contain as much—or more—sugar as aerated drinks. In 2020, products worth nearly Rs. 9 crores were seized by the Maharashtra Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for falsely being marketed as healthier alternatives to regular butter and dairy.

Yet, such established brands continue to hold sway over consumers because of brand loyalty and consumers’ inability to scrutinise labels. In a 2013 survey conducted in New Delhi and Hyderabad, most consumers said taste, price, and brand name guided their choices. When they did turn the pack over, they checked manufacturing and expiry dates, but rarely the ingredients list or nutrition table. Many felt that buying ‘trusted’ brands made checking such details unnecessary.

The regulation illusion

Ashim Sanyal, CEO of VOICE (Voluntary Organisation in Interest of Consumer Education), says there’s a principal dysfunctionality in the law, which allows brands to make unsubstantiated claims. “While generic phrases like ‘high in energy’ aren’t registered, brands can trademark variations of claims like ‘real juice,’ ‘100% juice,’ or ‘pure apple juice’ at the state or central offices of the Trade Marks Registry under the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPDTM). Once trademarked, other brands can’t use the exact same phrase, but it does give the illusion to customers that these are FSSAI-approved. However, in reality, these are statutory bodies with little knowledge about food regulation,” Sanyal says.

The loophole is that brands bypass nutrition regulations by embedding these terms in trademarks, which are governed by laws pertaining to trademarks, not food safety. “Only if a regulator happens to inspect a product (among the thousands launched everyday) that is in violation, then action can be taken.”

Bejon Mishra, founder of Patient Safety and Access Initiative of India Foundation (PSAIIF) and a former FSSAI member, confirms this misguided faith. A Consumer Welfare Fund, set up by the central government and intended to support ministries working on consumer awareness and redressal, lies largely idle. “State governments do not issue utilisation certifications if and when they use these funds, which is why the Centre refuses to further allot money. Ministries work independently, and consumer empowerment lies by the wayside. Instead, the [food and beverages] industry at large is cajoled, with their stakeholders dominating regulatory meetings,” Mishra says. Different regulatory bodies assess different parameters of food production, regulation and distribution–and work in silos.

Also read: Add crisis to cart: Why instant delivery and antibiotics don't mix

Consumer literacy and food sovereignty

The nutrition fact panel on the back of the product may have become a government mandate over the years, but the panel, combined with other elements, is filled with technical lexicon that makes it close to impossible for the lay consumer to discern. Even literate consumers living in cities cited a myriad of reasons for not pausing to peruse the table: the information was too dense and packed with jargon, the fonts too small, and the nutrients so unfamiliar that they were intimidated and demoralised.

Mumbai-based nutritionist Aditi Prabhu says that clients who often believed they were eating healthy were dismayed when they realised what the nutrition tables actually said. “I start with the basics and ask them to look at the ingredients list first—the shorter this list, the less processed it is,” Prabhu says.

Brands may include claims like ‘low-sugar’ on the front of the pack, in bold, intended to make consumers pick up the product. However, the panel at the back may reveal that it is high in other components—sodium, saturated fats, and other additives and preservatives. Instant soups and ready-to-eat mixes often fall into this category: marketed as light or wholesome, but carrying an eye-watering amount of sodium in a single serving.

“Brands have become very clever. They may claim there’s no added sugar. But there are over 60 types of sugars. The nutrition table might reveal aspartame, sucralose, glucose syrup, and some malt,” Prabhu adds. Similarly, a biscuit labelled ‘multigrain’ may still list refined wheat flour (maida) first, followed by sugar, palm oil, emulsifiers, and flavouring agents.

Even when people make the effort to decode the nutrition table, they often walk away with incomplete or only partially-understood information. As one consumer puts it in the 2013 survey, “Nutrition facts are there on labels…when buying for my father or mother…I check the fatty acids composition, especially trans-fats. But frankly speaking, I do not know what they mean exactly.” Label literacy could be a potential key to food sovereignty. But this model assumes a certain kind of consumer—one who is urban, educated and can be empowered.

The loophole is that brands bypass nutrition regulations by embedding these terms in trademarks, which are governed by laws pertaining to trademarks, not food safety.

Dipa Sinha, developmental economist and professor at Azim Premji University, says that affordability plays a determining factor. “Low income groups can only afford specific food items, which are often informally packaged (for instance, fried snacks and candies that are portioned into small, unbranded packets). They don’t always have the luxury to choose a ‘healthier’ alternative. Data shows that the proportion of income spent on processed foods is on the rise even among rural and poor populations, which contributes to existing problems like malnutrition, anaemia and stunting.”

She stresses that regulation must address both access and informed choice together. “Caste, gender and occupation shape what people eat in our country, whether it is farmers producing their own food, or intra-household distribution of food (women and girl children often go hungry in houses with inadequate food). Label-based interventions are necessary, but they won’t solve India’s nutrition problem,” she says.

“With pre-packaged foods migrating to quick commerce apps, often, the ingredients list and nutrition table aren’t updated, or even visible,” Prabhu adds. With more consumers making split-second choices on grocery apps, they are likely to go by taste alone, she says.

Also read: Traceability in Indian food supply chains: Complicated by costs, lack of incentive

The way ahead

Consumer organisations in India have been lobbying for Front Of Package Labelling or Front Of Package Nutrition Labelling (FOPL/FOPNL) since 2014, Sanyal states.

Given that packaged food has been linked with deteriorating health, there has been a consistent push by food scientists and medical professionals to adopt FOPL—a global practice proven to reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods. The variant of FOPL that Indian consumer advocates are calling for involves printing warning labels of whether a product is high in sugar, sodium or saturated fats (HFSS), based on standardised thresholds, on the front of the packet. This makes it visible, easy to understand and immediately indicates the nutritional pitfalls of the product to a consumer.

Label literacy could be a potential key to food sovereignty. But this model assumes a certain kind of consumer—one who is urban, educated and can be empowered.

The first draft of such an FOPL was based on a star-rating system, but was shelved soon after. “Star ratings are inherently suggestive of approval,” explains Prof. K. Srinath Reddy, Founder President of the Public Health Foundation of India. Following pressure from consumer organisations, the FSSAI released a revised draft in 2022.

“About seven of us consumer organisations are representing public interest in stakeholder meetings,” Sanyal says. At the heart of this advocacy is the belief that consumers deserve clarity, not persuasion. Rather than banning products, these groups argue for clear warning labels that counter industry-devised ideas of health and make nutritional risks immediately visible. FOPL, then, is not a one-stop solution, but a proposed intervention—premised on the idea that accessible information can shift choices, at least for some consumers. These details may not be what consumers memorise. But once noticed, they are hard to unsee.

Globally, FOPL has proved successful. Chile’s black octagonal ‘high-in’ labels cut sugary drink sales by 24% in just 18 months and Mexico saw a 12% drop in junk food consumption. Visual cues incorporated in FOPL can also be more inclusive than current nutrition labels in India, which are text-heavy and printed in only English and a select few regional languages. This method seems to clearly be more favourable to consumers. Is it then stalled because of marketers and advertisers, who may have more to lose if it comes into effect?

“Marketers do want what’s best for consumers as well, but often, it’s difficult to find that sweet spot,” says Geetika Singh, Director of Consumer Research at Ipsos, an MNC in market research. “Consumers are probably not going to buy a biscuit which is 100% husk, let alone pay a premium on it. They would probably much rather buy something that has some percentage of something ‘healthy,’ and other ingredients which make it tasty.”

Singh also reaffirms how brands try to profit off of consumer ignorance. They do want to provide information, but not at the cost of their own sales. A few flax seeds or ‘multigrain’ claims often mask a product that’s highly processed and high in sodium. It’s a case of ‘you didn’t ask, we didn’t tell.’

FOPL, then, is not a one-stop solution, but a proposed intervention—premised on the idea that accessible information can shift choices, at least for some consumers.

FOPL is one way of empowering the rural, illiterate consumer, Sinha says. “There simply needs to be a symbol that warns when a product contains components that may harm your health. It could be as simple as what has been achieved with tobacco and cigarette packaging,” she says.

Who is the Indian food label really serving? As ultra-processed foods become more central to the urban and rural diet, the burden of health literacy has shifted onto the consumer—one armed with little more than brand loyalty and a hard-to-read nutrition panel. Meanwhile, the industry continues to wield disproportionate influence over what is said, shown, and left unsaid on the packet.

Efforts like FOPL offer a chance to flip the script—to give consumers not just information, but clarity and an understanding of what's on our plate. There’s a higher chance of a consumer taking an easy-to-read label into consideration when adding items to cart on quick-commerce apps—translating into better public health too. Today, transparency remains an aspiration. Enforcing a pictorial warning-based FOPL will be a landmark decision in Indian food regulation history and policy. Until that shift happens, the label will remain fine print hiding in plain sight.

Also read: Ultra-processed foods are reshaping our diets. Should we be worried?

Edited by Durga Sreenivasan, Anushka Mukherjee, and Neerja Deodhar

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References