The solution lies not just in tightening rules, but also reducing the cost of compliance

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

As consumers, do we have the right to know more about where our food comes from? With food borne illnesses and lifestyle disease statistics making headlines frequently, this is a fair question, but also one that is difficult to answer. Modern supply chains are vast, and even seemingly single-ingredient foods often come from multiple sources. Tea may be blended from several estates, coffee from different regions and honey from hundreds of small apiaries. For foods with many ingredients, tracing each component is even more challenging.

For consumers, this information is not always useful. What most people need is reassurance that the food they buy is safe and stands up to the various claims made on its packaging. For businesses and public authorities, however, knowing where each ingredient comes from is essential. When contamination or adulteration occurs, they must be able to identify where the problem began and act quickly to remove affected products. A reliable traceability system is therefore less about telling consumers every detail of origin, and more about ensuring that producers and regulators can track the chain of responsibility when needed.

Traceability, from paperwork to digital records

In the past, supply chains were short and local, allowing producers and consumers to maintain direct relationships built on trust. Industrialisation and the consequent globalisation of food trade weakened those connections. As food began to move across states and countries, it became necessary to create systems that could record where a product came from, how it was handled, and where it was going next.

The modern understanding of traceability developed between the mid to late twentieth century when several food crises exposed weaknesses in existing systems. Globally significant events such as the outbreak of the mad cow disease in Europe in the 1980s and the adulteration of Chinese infant formula with melamine in 2008 had far reaching public health consequences, pushing countries to recognise traceability as essential to public health. In the 1960s, the Codex Alimentarius Commission, a joint body of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), set international standards for food safety and fair trade. It defines traceability as ‘the ability to follow the movement of a food through specified stage(s) of production, processing and distribution’. The Commission regularly revises its guidelines to reflect new scientific developments, and its framework serves as the foundation for most public and private traceability systems worldwide. Today, traceability in food supply chains has moved from paper records to digital systems that use barcodes, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology and even blockchain, making it possible to trace the source of even the most minute ingredients in products that have travelled halfway across the world.

Also read: A new science-backed Planetary Health Diet is in the spotlight. How does the Indian diet measure up?

The Indian scenario

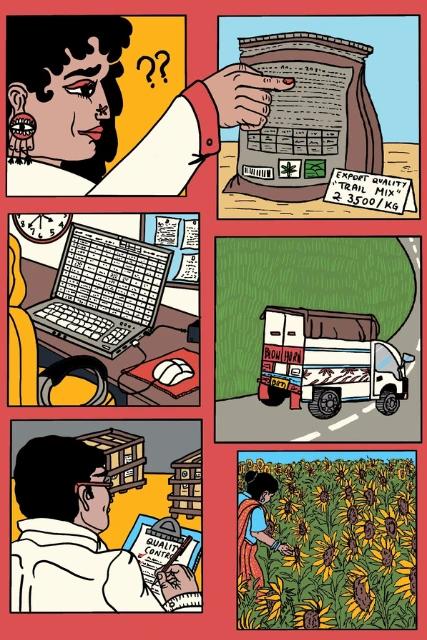

Indian agriculture is dominated by rural smallholders. A single supply chain can include hundreds of farmers cultivating small and scattered plots of land. Many have limited access to smartphones, stable internet or digital literacy tools. Similarly, processing activities are undertaken by lakhs of small and medium sized factories around the country. Transactions are still recorded on paper, and even when they are digitised, they are often not managed effectively. Tracing the source of an ingredient can therefore mean searching through paper ledgers or incomplete digital files instead of accessing a well-maintained database.

Export markets, where transparency is rewarded through price premiums and market access, make such investment worthwhile. In contrast, domestic buyers rarely pay more for traceable produce, so food businesses have little incentive to adopt these systems.

Developing robust traceability systems is also expensive. Setting up the digital infrastructure, organising audits, obtaining certifications, and training quality assurance and administrative personnel requires continuous investment. For small producers operating on narrow margins, these costs are difficult to bear unless traceability leads to higher returns. Export markets, where transparency is rewarded through price premiums and market access, make such investment worthwhile. In contrast, domestic buyers rarely pay more for traceable produce, so food businesses have little incentive to adopt these systems. As a result, export-oriented supply chains in India have developed strong traceability systems, while those serving domestic markets often rely on fragile documentation practices and informal networks of trust among the many actors involved.

The Food Safety and Standards Act of 2006 provides the legal basis for food control in the country, while the Food Recall Procedure Regulations of 2017 require manufacturers to withdraw unsafe food and communicate with consumers when necessary. In 2022, a survey of 30 food businesses in Delhi and the National Capital Region revealed how limited domestic traceability remains. Nearly all participants used barcodes to display retail prices, but only a small fraction maintained recall or traceability protocols. Many companies were unaware of how to trace products backward to their source or forward to distributors in case of a safety issue. This suggests that the tools of traceability exist but are used primarily for labelling and pricing, not for safety or accountability.

Sustainability certifications rely on detailed records that show where ingredients come from, how they were grown, and which standards were followed at each stage of production. Without this chain of evidence, sustainability labels would have little meaning.

Milk, for instance, is a product where quality lapses continue to be reported. Raw milk often moves through a chain of village collectors, chilling centres, transporters, and small dairies before it reaches consumers, and problems can arise at several points along this route. Periodic surveys by public authorities and independent researchers have found both dilution and the use of substances such as detergent in different regions. Paneer faces comparable challenges. Alongside batches made from low quality milk, there is a growing market for analogue paneer made with processed vegetable fats and other non-dairy ingredients. This can amount to food fraud when such products are sold as paneer without clear disclosure, leaving consumers unsure of what they are actually purchasing. Much of this activity takes place in small, informal units with limited records, so when adulteration or mislabelling is detected, authorities often struggle to identify the specific source and must issue broad advisories instead of targeted action.

The weaknesses in domestic traceability have contributed directly to recurring cases of contamination, adulteration and foodborne illness. The FSSAI frequently issues alerts and recalls, and one of the most prominent recent examples involved packed spice blends, which came under scrutiny both abroad and at home in 2024, after multiple countries detected the carcinogenic pesticide ethylene oxide in popular brands. Weak traceability systems mean that investigations must rely on manual records, supplier declarations, and blanket bans leading to financial losses for businesses and an erosion of trust among consumers.

From safety to sustainability

Traceability today goes beyond food safety and has become an important tool for ensuring environmental and social sustainability as well. Sustainability certifications rely on detailed records that show where ingredients come from, how they were grown, and which standards were followed at each stage of production. Without this chain of evidence, sustainability labels would have little meaning. An organic label is based on proof regarding a production system being free from synthetic fertilisers, pesticides and genetically modified inputs. Fair trade certification verifies that farmers receive fair prices and work under safe conditions. Other claims, such as ‘rainforest certified’ or ‘shade-grown’, are linked to biodiversity protection, while ‘cage-free’ and ‘free-range’ labels concern animal welfare.

Sustainability certifications such as these are often treated as add-ons that signal higher ethical or environmental value and therefore command a price premium in the market. In the Indian context, as with food safety, such traceability systems are found mostly in export-oriented sectors. Products sold domestically seldom undergo the same level of verification, and sustainability claims remain limited to a small, urban consumer base that can afford to pay more for them.

Inclusive development

Setting up traceability systems is an expensive affair, and it is usually large manufacturers, supermarket chains, and export-oriented companies that have the resources to build and maintain them. For smaller suppliers and local retailers, the same requirements are far more difficult to meet. When only large companies can afford to meet compliance requirements, supply chains begin to be increasingly controlled by them. To ensure that every product can be traced, these firms often bring more of the production process under their direct control, a strategy known as vertical integration. In a vertically integrated supply chain, a company owns or manages several stages of production, such as farming, processing, packaging, and distribution. This can make traceability easier, but it also concentrates decision-making power, leaving less room for small and independent actors.

Instead of simply tightening rules, regulators can focus on reducing the cost of compliance.

Public supervision can help avoid this outcome. Regular inspections and transparent monitoring by government authorities can make traceability a shared responsibility rather than a private asset. Instead of simply tightening rules, regulators can focus on reducing the cost of compliance. Affordable digital tools, publicly funded data storage platforms and simplified reporting formats would allow small and informal businesses to meet basic traceability standards without being forced out of the market. This is especially important in India, where about 1.2 crore kirana stores account for more than 90% of sales in the Rs 67 lakh crore ($810 billion) food and grocery market. These small businesses are central to the economy and to the daily lives of ordinary consumers, which makes it essential that systems of safety and accountability are designed to include them. Additionally, penalties for deliberate fraud and mislabelling remain necessary not only to deter malpractice, but to protect public health—and ensure that honest and compliant businesses can compete fairly, without being undercut by those who cut corners.

Also read: Ultra-processed foods are reshaping our diets. Should we be worried?

Artwork by Alia Sinha

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

.avif)