India falls short on protein and could do better with whole grains. Its ghee consumption raises concerns

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

On October 2, 2025, the EAT-Lancet Commission, a global consortium of 70 scientists from 35 countries working at the intersection of nutrition, health, and sustainability, released an updated version of its landmark 2019 report, which first introduced the idea of a Planetary Health Diet (PHD). Like many food systems researchers around the world, I have been busy parsing the report and assessing how its updated evidence base reframes global discussions on sustainable and healthy diets. For anyone who has read the 76-page report and its supplements, its scale and scope are immediately evident. It brings together an extraordinary range of evidence across disciplines, leaving much to be discussed.

In this column, however, I focus on the PHD and explore how the average Indian diet stacks up against its vision for healthy and sustainable eating. The PHD is framed as an optimal diet for improving the wellbeing of the global population and has been developed based on the health impacts of consuming various foods. However, the report provides evidence indicating that the widespread adoption of such a diet can reduce the negative environmental impacts associated with most current diets, making it a means to improve the health of people as well as the planet.

By no means are my observations a report card of the Indian diet, for it remains unclear whether the PHD is entirely suitable for the developing country context (more on that in the last section), but rather an attempt to understand where India’s eating patterns stand in relation to its principles.

The 2025 Planetary Health Diet

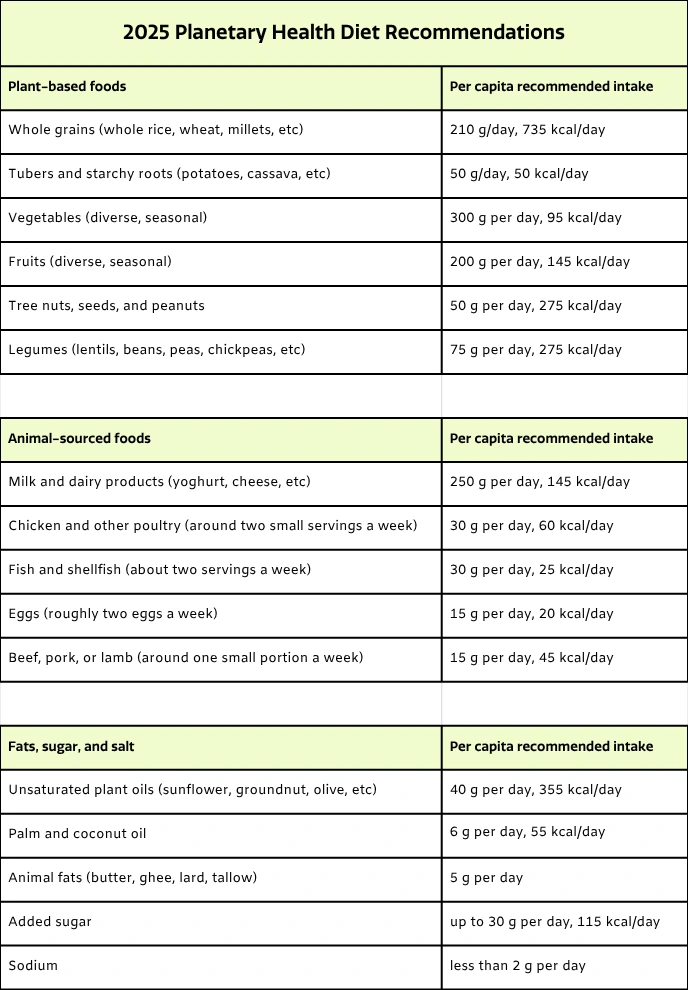

The 2025 PHD serves as a global reference framework that must be adapted to local cuisines and food systems, as well as to individual characteristics such as age, sex, body size, physical activity level, pregnancy and lactation status, health condition, and genetics. The diet, based on a 2400 kcal energy intake per day, recommends consuming generous quantities of plant-based foods like fruits and vegetables, moderate amounts of animal-sourced foods, and minimal quantities of ultra-processed foods, added sugar, saturated and trans fats, and salt. Here’s what it recommends per food group:

How does the average Indian diet compare?

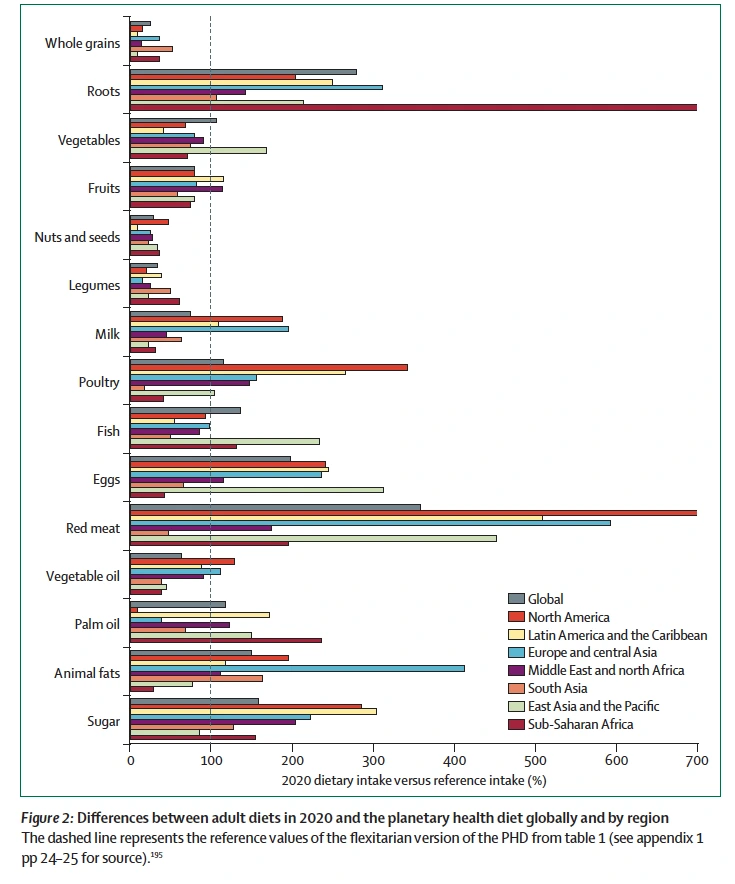

The EAT-Lancet report compares its recommended diet with average dietary patterns across different world regions. India is grouped within the South Asia region, and while country-level comparisons for the 2025 report are not yet available, regional averages offer a useful reference point. Let’s take a look for each macronutrient category.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates form the foundation of most diets, and within the PHD framework, whole grains, tubers, fruits, vegetables, and sugar are the key components to consider. Global whole grain intake is far below recommended levels. South Asia fares better than all other regions of the world (rotis to the rescue!) but still only meets half the target. This does not mean grains are lacking in Indian diets; rather, they are mostly consumed as refined products such as maida and polished white rice. Recent research by the Indian Council of Medical Research shows that Indian adults derive roughly 62% of total energy from low-quality carbohydrates, largely refined cereals and added sugars. The same study shows that high carbohydrate intake is associated with a higher likelihood of non-communicable diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases within the population. In many low- and middle-income countries, whole grain foods are less available and more expensive, partly because the nutrient-rich bran and germ are removed and sold as animal feed.

Tuber consumption in South Asia roughly aligns with the PHD recommendation, though our fondness for potatoes shows through as the average slightly exceeds the suggested limit. Sugar intake surpasses the suggested level by about 25% but remains well below that of regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean and North America. Fruit and vegetable intake in the region remains below recommended levels, with vegetables faring better than fruits, for which South Asia records the lowest consumption among all regions.

Protein

Let’s turn to protein. Consumption trends for plant-based foods such as nuts and legumes, and animal-sourced foods like milk, poultry, eggs, fish, and red meat, tell an interesting story. Globally, average intakes of nuts, seeds, and legumes fall well below the levels recommended by the PHD. South Asia performs relatively better, ranking second only to Sub-Saharan Africa in legume consumption. But even here, the average intake is only about half of what the PHD suggests, even though lentils and pulses feature so prominently in the region’s culinary traditions.

While reducing excessive meat intake is crucial in many parts of the world like North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and Central Asia, in India the challenge is the opposite: ensuring that people consume enough high-quality protein from both plant and sustainable animal sources to meet their nutritional needs.

For animal-sourced foods, South Asia’s averages are similarly below the recommended levels: eggs at roughly 75%, fish and milk around 50%, red meat about 50%, and poultry between 15 and 20% of the PHD targets. Among all regions, South Asia shows the lowest levels of poultry, fish, and red meat consumption. Earlier research comparing the 2019 PHD with Indian dietary patterns found consistently low caloric intake from protein sources, both plant- and animal-based, across all regions, sectors, and income groups. The deficit was most pronounced in rural areas, where only about 6% of total calories came from protein, compared with 29% in the 2019 reference diet.

At first glance, the region’s relatively low consumption of animal-sourced foods might appear environmentally beneficial, especially when compared with the high levels typical of North America, Europe, and parts of Latin America and even Sub-Saharan Africa. However, this gap also points to a serious protein inadequacy in South Asian diets. While reducing excessive meat intake is crucial in many parts of the world like North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and Central Asia, in India the challenge is the opposite: ensuring that people consume enough high-quality protein from both plant and sustainable animal sources to meet their nutritional needs.

Also read: Ultra-processed foods are reshaping our diets. Should we be worried?

Fats

When it comes to fats, South Asia shows an interesting mix of alignment and excess. Vegetable oil consumption is close to 40% of the amount recommended by the PHD. Most other regions fall short of this benchmark, with only North America and Europe and Central Asia slightly exceeding it. Palm oil consumption in South Asia is around 70% of the recommended level, a more moderate figure than in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa or East Asia and the Pacific, where it is considerably higher. Palm oil is not traditionally part of South Asian diets, but its low cost and long shelf life have made it a preferred ingredient in the food processing industry.

This does not mean grains are lacking in Indian diets; rather, they are mostly consumed as refined products such as maida and polished white rice.

Animal fat consumption, on the other hand, tells a different story. At roughly 60% more than PHD’s recommended amount, it is the only food group in which South Asia significantly exceeds the recommended level. This likely reflects the region’s enduring fondness for ghee and other dairy fats, both in home cooking and festive cuisine. While these fats hold cultural and culinary importance, their high saturated fat content raises concerns for cardiovascular health, particularly as diets become more energy-dense and lifestyles more sedentary.

The NIN’s dietary guidelines for Indians

The EAT-Lancet commission strongly urges public authorities to adapt the principles of the PHD to local nutritional needs and cultural preferences via national dietary guidelines. In the Indian context, the National Institute of Nutrition’s (NIN) dietary guidelines are interesting to consider in this regard. Released in 2024, the guidelines do not make any reference to the PHD. However, both guidelines present many overlaps. Since the PhD is based on a 2400 kcal intake and the NIN’s guidelines on a 2000 kcal one, it is not possible to compare recommended quantities for various foods directly. However, both propose a diet that is rich in vegetables and pulses and moderate when it comes to animal-based foods, fats, and sugar.

Some differences between the PHD and NIN guidelines are worth discussing here as well.

Some differences between the PHD and NIN guidelines are worth discussing here as well. For instance, while the PHD allows about two eggs per week, the NIN recommends one egg a day. It also recommends fruits in much lower quantities than the PHD. These differences reflect India’s specific nutritional deficiencies, affordability concerns, and access issues. But some other differences might hint at blind spots. For example, the NIN guidelines group oils and fats together with nuts, without clearly distinguishing between animal-sourced or saturated fats and healthier plant-based options. Such an approach risks overlooking the excessive consumption of animal-sourced fats, which the EAT-Lancet report identifies as a dietary concern in South Asia. The NIN also classifies tubers like potatoes under vegetables, whereas the PHD treats them as a separate category with a limited share of the diet.

Also read: What it takes to feed India’s growing cities

Beyond the plate

The 2019 EAT-Lancet report was criticised for proposing a diet that was out of reach for much of the developing world. A 2020 study found that the cost of an EAT–Lancet diet, even when adapted to local contexts, exceeded household per capita income for at least 1.58 billion people. The recommendations of the 2025 report do not deviate much from the 2019 ones (though they do come with stronger evidence) even as consuming fruits, vegetables, nuts, and even meat in quantities suggested by the PHD remains unattainable for people in most developing countries including India.

All in all, while it might be unrealistic to expect the Indian population to consume 500 g of fruits and vegetables and 50 g of nuts and seeds every day, there are areas where policy action can make a meaningful difference.

Affordability is only one part of the picture. The report also draws attention to a stark imbalance in responsibility: the wealthiest 30% of the global population account for over 70% of food-related environmental impacts, and diets in regions such as North America and Europe have a far greater environmental footprint than those in South Asia. This contrast raises an important question—should a country like India be expected to change its diet when it contributes far less to global environmental degradation? I believe the answer is still yes, not for environmental reasons alone, but because the framework speaks directly to urgent public health needs.

There is much that the government can do with the analysis presented by the report. To begin with, understanding how India eats requires better evidence. Research that compared the Indian diet with the first EAT-Lancet’s PHD relied on national consumption data from 2011–12, the last comprehensive survey of its kind. National level data from 2018–19, which could have provided an updated picture, could not be used because of quality concerns. Without new data, policy design risks being reactive and fragmented.

The widening gap between those who can afford diverse, nutrient-rich foods and those who cannot is also an area that must be addressed by the government. Urban and higher-income populations have greater access to diverse and nutrient-rich foods, while rural and poorer households remain dependent on cereal-heavy diets. Food price volatility, insufficient government aid, and uneven social and economic development across regions have deepened these divides.

All in all, while it might be unrealistic to expect the Indian population to consume 500 g of fruits and vegetables and 50 g of nuts and seeds every day, there are areas where policy action can make a meaningful difference. Expanding subsidies and procurement support for whole grains, pulses, and fresh produce, alongside public campaigns to reduce sugar and animal fat consumption, would help shift diets in a healthier direction and curb the incidence of non-communicable diseases. Strengthening the Mid Day meal programme and public distribution schemes to prioritise nutrient-rich foods could also help bridge dietary gaps without placing additional burdens on households. Steps such as these should be taken in order to strengthen nutritional security and the resilience of India’s food system in the face of environmental and economic pressures. Because, after all, the wellbeing of one-sixth of humanity cannot be separated from the wellbeing of the planet itself.

Artwork by Alia Sinha

{{quiz}}

References

.avif)