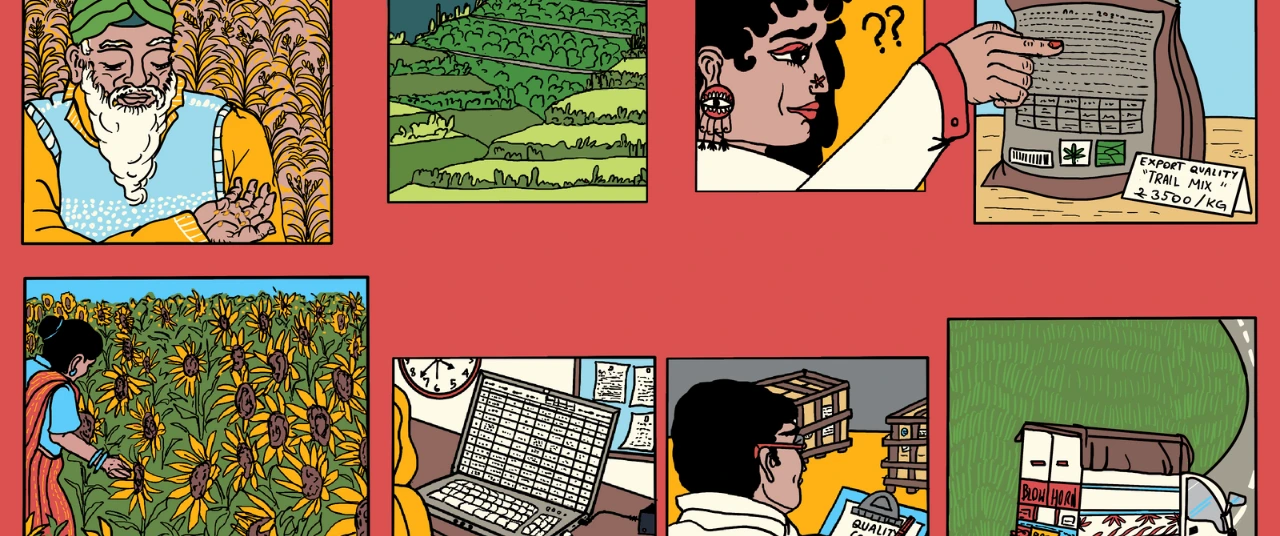

A fresh take on farming that connects growers and eaters

Beejom, a sustainable farm in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh, cultivates a diverse range of naturally grown produce, including black turnips, violet broad beans, black rice, millets, legumes, oilseeds, herbs, and fruits. Established in 2014 by lawyer Aparna Rajagopal, it started on a piece of leased land in Noida before expanding into its own space. The farm operates on a community-supported agriculture (CSA) model, where urban consumers subscribe to seasonal produce baskets, embracing the farm’s ebb and flow. In addition to selling grains and dry produce at a weekly farmers’ market, Beejom welcomes visitors for weekend farm brunches, serving fresh, homegrown meals while fostering direct engagement with customers.

Beejom illustrates the CSA model in India, linking farmers and consumers through seasonal produce subscriptions. Customers embrace the unpredictability of harvests while supporting sustainability and enjoying fresh, chemical-free food. This system strengthens local food networks and reduces dependence on commercial supply chains.

CSA embraces a shared dedication to creating a more localised and fair agricultural system. It enables farmers to prioritise sustainable farming practices while ensuring their farms remain productive and profitable. Rooted in personal connections, CSAs strive to strengthen communities through a shared focus on food. It is a farming approach where consumers subscribe to seasonal produce, directly backing farms and sharing the rewards and risks of cultivation.

Unlike traditional agriculture, which depends on intermediaries, CSA fosters direct connections between farmers and consumers. Subscribers commit to the farm’s yield, accepting natural variations caused by weather or pests. Many farms adopt organic, permaculture, or biodynamic methods to enhance soil health and biodiversity. Some also engage members in farm activities, deepening their connection to food production. By prepaying for seasonal shares, consumers receive a variety of produce while gaining insight into farming challenges, ensuring small farms a steady income and financial security.

Also read: Farmer’s Share offers a model for boosting farmers' income

Trust the process

The shift towards online food and grocery services has altered consumer behaviour, making it challenging for small businesses like Beejom to sustain themselves. With more people opting for takeout and delivery instead of home-cooked meals, the demand for fresh ingredients has declined. To address this, Beejom actively engages customers by preparing and selling meals made from their own produce and sharing recipes through WhatsApp groups. The farm also advocates reviving Indian millets and traditional foods to promote food security, health, and sustainability. By incorporating solar energy, biogas, rainwater harvesting, and vermiculture into its everyday functioning, Beejom can be self-reliant in its waste management, electricity generation, and water access. Dedicated to grassroots efforts, it collaborates with farmers to transition to organic farming, emphasising that access to clean and nutritious food is a fundamental right.

“The group has 30 consumers from the city, who give us a list of produce that they prefer, and every Friday and Tuesday, we deliver a mix of vegetables and seasonal fruits to them,” says Deepa N, a young farmer from Kariyappanadoddi village in Karnataka. She works under the Mayuri Vanashree Shakti Okkuta, a self-help group (SHG), which is part of an initiative started in April 2024 called ‘Kai Thota’ (“kitchen garden” in Kannada) by the Buffalo Back Collective (BBC). The Buffalo Back Collective was founded 12 years ago by Vishalakshi Padmanabhan, who has dedicated herself to discovering and safeguarding rare, ancient grains and seeds. The core philosophy behind her organic store is shaped by the food values she was raised with, minimising waste and appreciating every resource. She and her husband left their corporate jobs to purchase land in Kariyappanadoddi, 30 km from Bengaluru, where their journey began.

The Buffalo Back Collective is an organic farming collective designed to create mutual benefits for farmers, consumers, and the environment. It retails its products at an outlet in Bengaluru. All the consumers are members of the consumer federation created for the Collective, which mainly comprises people who are worried about food systems and want to make better choices, but cannot grow their own food.

Under the Kai Thota initiative, women from an SHG have leased a 1-acre plot to cultivate crops, allowing consumers to subscribe to 1,200 sq ft sections for a fixed fee. Farmers oversee cultivation, estimate yields, and deliver fresh produce twice a week while maintaining direct consumer engagement. “We set up the whole format for the farmers, including a sowing calendar, the pattern and how to manage seasonal produce, surpluses and deficits,” Padmanabhan says. The idea was to involve women SHGs in directly growing vegetables for consumers.

Also read: Regenerative farming: Solution to climate change?

Growing interest

Recent trends show a rising interest in CSA among Indian consumers, fuelled by a greater awareness of health, environmental sustainability, and the need to support local economies. This change aligns with a global movement toward more localised and transparent food systems. Navadarshanam and Farmizen, both Bengaluru-based, and Solitude in Auroville, are among the several CSA initiatives striving to develop sustainable and meaningful solutions that benefit both farmers and consumers.

Sahaja Samrudha Organics was established in 2010 under the Producer Act. This provision enables the formation of “producer companies” (legally recognised groups of farmers/producers who work together for production and procurement to enhance their incomes), allowing farmers to collaborate in production, processing, and marketing while leveraging collective benefits. It operates on a distinctive model of being entirely owned by organic producers dedicated to environmental preservation while offering various nutritious and sustainable food products. “All the farmers working with us are also shareholders of the company. We procure from the farmers and sell their produce; we ensure that we pay a premium price to the farmer, the annual profits go back to the farmers in the form of patternised bonus, and we also pay them a dividend based on their shareholding with us,” says Somesh B, CEO of Sahaja Samrudha Organics in Bengaluru.

Why CSA makes sense

There are several essential features to CSA, which are a win-win for both the producer and consumer, and the environment. “Production planning is much easier for a producer or producers' collective if they have steady and predictable consumer community support,” says Kavitha Kuruganti, a social activist with the volunteer group ASHA Kisan Swaraj. According to her, stable prices help the budgets of both the producer and the consumer. Very often, market options for a producer become restricted due to a lock-in period or clause with creditors. The way most CSA models operate, even the financing requirements of the producers are smoothened out, and more market options open up. For the consumer, safe food is assured in a verifiable manner.

Also read: Farmers demand a fair shake with minimum support prices

Gaps in the system

“What’s happening these days in the name of CSA is that they are only an investment on the land, and this is nothing but real estate or a business model. Real CSA happens when consumers can interact with the producers, and directly buy from the producers,” says Dr. G. V. Ramanjaneyulu, founder of the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture in Hyderabad. The Centre researches agroecological farming practices and their effects while supporting farmers and consumers in successfully shifting to organic methods. He believes it becomes challenging when consumers approach it as merely a business opportunity, as this mindset undermines the core purpose of producing clean food and fostering a meaningful connection between farmers and consumers.

.avif)

CSA initiatives face many challenges, such as consumers' lack of awareness of the model, making it difficult to establish a loyal customer base. Small-scale farmers struggle with startup costs, ongoing expenses, and fluctuating demand, which threaten long-term sustainability. Moreover, managing storage, transportation, and timely delivery of fresh produce presents logistical challenges, which, when coupled with unpredictable weather and seasonal fluctuations, affect crop yields, leading to inconsistencies in supply.

Explore other topics

References

.avif)