In Agoratoli village in northern Assam, the Mising live in bamboo houses on stilts in response to the region’s annual floods. The village lies in the Brahmaputra’s riverine landscape, shaped by shifting waters and sedimentation that form chars—semi-permanent sandbars and islands that appear and disappear with the river’s flow.

The community has a deep-rooted connection with the region and the Kaziranga forests. Historically, the Mising have foraged, fished, practised agriculture and reared livestock in and around it.

Women use traditional fishing instruments like the Jakoi, Saloni and Poloh to scoop fish from rivulets and shallow pools from the paddy fields. The fields of Bao dhan, an indigenous rice variety, require long hours of water immersion and become a natural breeding ground for fish hatchlings.

Community elder Numal Kardong skillfully weaves together a sepa, an elongated cane instrument. When immersed in water, the fish swim in through its open mouth and are trapped inside.

Kardong’s grand-nephew Ritupan Pegu remembers how his community lived alongside the Kaziranga National Park when he was a child. Now, boundaries have been drawn. Kaziranga eats into ancestral land, and the Misings’ access is increasingly limited by barricades and no-entry zones.

Kardong’s wife, Muguri, has freshly harvested an assortment of leaves for the Namsing paste, including Bihlongoni [Eagle Ferns], Kosu paat [Taro leaves], Siju [Indian spurge leaves], Bhul [Sponge gourd leaves] and Haldi paat [Turmeric leaves].

Namsing utilises the young of freshwater carps, barbs, and other smaller riverine fish which are perishable. During the monsoons, when there is a glut of these varieties, they are preserved by smoking. Muguri has dried an assortment of fish for a month on the bamboo Perup above the hearth.

Preparing Namsing is a communal activity. Mising women gather to pound the mix of fish, herbs, chillies, salt and turmeric with the haat-dekhi. The forest echoes with gentle thuds as the women fall into a familiar rhythm.

The fresh batch of Namsing is tightly packed in a bamboo tube and sealed with salt, a turmeric leaf, straws, and some loose soil. It will then be left on the Perup, where it can last for over a decade without any infestations.

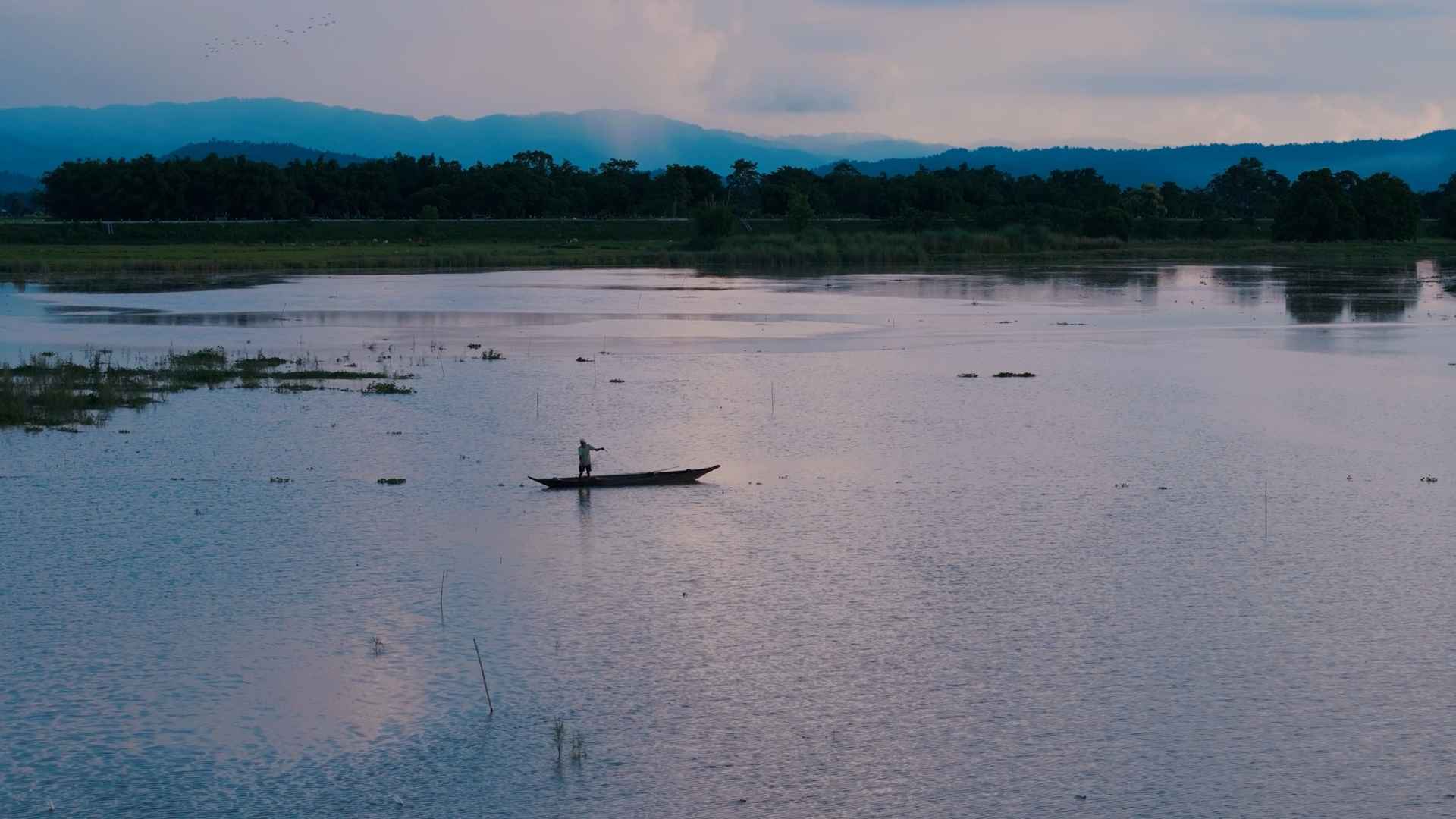

Indigenous communities understand where fishing grounds and wildlife corridors exist, and how to preserve them. Ecosystems need people too—the local inhabitants remove water hyacinths that allow wetlands to regenerate.

However, infrastructural developments undertaken to protect the National Park disregard community-based conservation. Forest laws exist to protect against the misuse of natural resources. But the complex legal quagmire surrounding tribal rights over forest land and resources allow the state to frame them as intruders and dispossess them.

The construction of sluice gates on the Brahmaputra has impacted the amount of water that flows through. Its tributaries on the ‘public’ side of the Kaziranga lie stagnant. “Have you ever seen a river that does not flow?” asks Ritupan Pegu.

Fewer people prepare Namsing now. Many of them have to buy dried fish from markets to make the fermented delicacy. “We don’t know if this knowledge will pass onto the next generation when our land will become part of the Park,” says Kurdong.

With Namsing, a little goes a long way. Everyone takes a little of this chutney that is smoked in the coals and then mixed with roasted fish, and paired with pork curry and rice. Even as an uncertain future looms over their homes in the Kaziranga forest, the Mising gather for feasts centered around a delicacy that carries the taste of fish from a bygone time. For now, the tradition endures.

.webp)