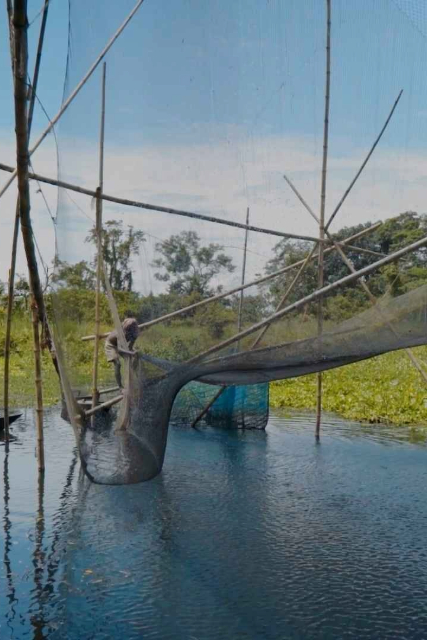

Pokkali fields allow for the integrated farming of paddy and prawns. Central Kerala’s Pokkali fields bear a striking resemblance to the Kaipad farming system practised in the state’s northern region; both methods rely on the natural tidal ebb and flow.

The presence of migratory birds like the Little Cormorant in large numbers points to the abundant availability of fish in Kadamakkudy.

Leela works in the muddy field from the break of dawn till noon.

Once it is caught with bare hands, the catch is held tightly in the fisher’s mouth before it is dropped into an aluminium pot whose opening is covered with leaves to prevent the fish from jumping out and escaping.

When they sense the presence of humans in the water, karimeen (pearl spot fish) tend to lie motionless in the mud to protect themselves. Having observed this behaviour, fishers are able to catch them rather easily.

Leela’s age may come as a surprise to those who are unfamiliar with Kerala’s fishing traditions. These methods, which require half of the fisher’s body to be immersed in the mud, are largely carried out by the older generation.

A long day of work has yielded a relatively small amount of fish. Yet, having spent hours in muddy water makes Leela vulnerable to health risks like skin infections.

The illegal dumping of waste has posed a major threat to traditional fishing in Pokkali fields and swamps. The careless disposal of glass bottles, for example, has made fisherfolk vigilant about possible injuries as a result of broken shards.

There are takers for live fish, too. For the price of Rs 50, Leela hands over a bag filled with fish kept stable in water.

Years of practice and routine have enabled Leela to skilfully catch shrimp, crabs, karimeen, choottachi (orange chromide), and clams.

She smiles as she prepares to return home. Amid changing dietary needs, as consumers make more responsible choices and seek out cleaner, less commercial options, the work of traditional fisherfolk assumes a greater significance.