Aisiri Amin

|

March 3, 2026

|

12

min read

Bibijan Halemani dared to dream—of millets, and a better world for women

Halemani’s award-winning self-help group in Karnataka runs a seed bank and instills new confidence in millet cultivation

Read More

Habitat degradation and a slow approach to conservation and aquaculture have put the beloved Pearlspot or Green Chromide at great risk

In the brackish backwaters of Kerala, there exists a fish so beloved that songwriters liken it to the kohl-lined eyes of women. A culinary superstar and heritage treasure akin to Bengal’s Hilsa, to eat it is to consume a part of Kerala itself: a product of a terroir that carries within it the sweetness of fresh water and the salt of the sea. When it arrives on the dinner table stewed in spiced coconut milk or wrapped in a banana leaf, a story far older—and stranger—than any recipe begins to unravel.

The fingerlings of the Pearlspot or Karimeen, the young of the fish just one stage away from being adults, are tender ghosts of the mangrove's shade. The fish thrives in the fragile balance between two worlds—gliding the cool currents of the shallows where rivers first yield, as well as the waters of the briny sea.

The Karimeen's ancestors swam in the Tethys Sea, the ancient ocean that once separated the northern and southern supercontinents. When Gondwanaland, the primordial landmass that cradled India and Madagascar together, began its slow fracturing millions of years ago, these fish adapted, evolved, and learned to thrive in the shifting salinity of brackish waters. They became euryhaline survivors—creatures equally at home in freshwater and saltwater, embodying in their very biology the secrets of a continent's rupture.

But today, as Kerala's backwaters face unprecedented stress, from pollution to damming, from agricultural runoff to urban sprawl and the entry of invasive piscine species, the Karimeen finds itself swimming through a radically altered world. The fish that once filled nets and pots in such abundance that it defined regional cuisine, has now grown scarce. A reminder that even creatures shaped by millions of years of evolutionary adaptation can falter when change accelerates beyond their capacity to respond. “We can’t rely on the Karimeen alone for our livelihood like we used to,” says Arun, a fisherman who operates out of Fort Kochi. Originally from Vypeen, an island in Kochi’s backwater estuary, Arun started fishing Karimeen at the age of 10 with his bare hands.

They became euryhaline survivors—creatures equally at home in freshwater and saltwater, embodying in their very biology the secrets of a continent's rupture.

The process, called Thappal, is intimate and arduous, Arun explains. Fisherfolk stand waist-deep in silt-heavy backwaters with their bare legs serving as anchors, while their arms plunge deep into the muck. Groping with fingers spread wide, gently sweeping the opaque bottom, they feel for the current of life: the twitch of a tail fin, the subtle shift in the mud, or the sudden warmth of a body against the cooler silt.

This practice, often carried out by experienced fishermen, involves casting a weighted circular net into the water, letting it sink and spread, and trapping the fish underneath before catching them by hand. Some others use cage-like traps in shallow waters that are baited and left overnight.

But, in the spawning period, if one is not careful of overfishing, fishing itself could become unsustainable. “Back in the day, my father only caught Karimeen and that was enough. As a kid, I’d accompany him. But now, we do all sorts of jobs just to get by,” says Arun, now in his 40s.

{{marquee}}

Beyond its culinary significance and contribution to livelihoods, the Karimeen is a living relic—a key to unlocking the mysteries of the Earth’s ancient past. In 2012, Scottish geologist Iain Stewart visited Kerala with his BBC crew while filming Rise of the Continents, a documentary series exploring the origins of Earth’s landmasses. His journey to the southernmost tip of India was a quest to understand the Karimeen and its evolutionary significance. Thriving in Kerala’s backwaters, the fish could hold a vital link to Gondwanaland.

Stewart traced the Karimeen’s evolutionary ancestry over 100 million years to the Tethys Ocean, which separated Gondwanaland from Eurasia. As the Indian landmass drifted northward, the fish’s relatives remained scattered across the remnants of Gondwanaland, evolving in isolation. Today, the Paretroplus cichlids of Madagascar are the Karimeen’s closest cousins, a living testament to how geological upheavals shaped biodiversity across continents.

Scientifically known as Etroplus suratensis or Green Chromide, Karimeen is the largest cichlid fish endemic to Peninsular India and Sri Lanka. The fish has an elevated, laterally compressed body and a small cleft mouth. Primarily found in the brackish waters of estuaries, lakes, wetlands and rivers in Kerala, the Karimeen holds cultural and economic importance in the region.

As a bottom feeder—scavenging from the seabeds of waterbodies for food—the Karimeen benefits from the availability of an abundance of nutrients, enabling it to grow quickly and thrive.

It develops through about six life stages: after the egg hatches, the larvae—colourfully called the “wrigglers”—start writhing in six days’ time. In a few weeks, the young learn to tolerate salinity and start swimming freely; they feed on zooplankton, insect larvae and algae, depending on their age. The next stage is the fingerling, when the fish is a few months old; it starts resembling the adult with faint shadows of its characteristic spots. Fingerlings are often fished and stocked for aquaculture, carefully grown in supervision until maturity in a tank or controlled lake, as opposed to open waters. After a year of age, the Karimeen is an adult, soon ready to reproduce. The average adult is about the size of a grown man’s hand.

A euryhaline fish, Karimeen can tolerate a wide range of salinities by actively regulating its internal salt and water balance through osmoregulation—an essential adaptation for survival in fluctuating aquatic environments. The fish’s elliptical body features shiny spots which lend it its English name, Pearlspot. Soft with flaky meat in a maze of strong, sharp bones, the fish is incredibly delicious, although some may find it slightly challenging to eat.

“Even though it’s found in states like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, the Karimeen thrives in brackish water and certain freshwater sources of Kerala. Places like the Kochi backwaters are an ideal habitat for the fish because they are rich in organic matter. These backwaters receive drainage as well as organic nutrients from the rivers connected to them, creating fertile waters,” says Vishnu Bhat, former Fisheries Development Commissioner. He explains that as a bottom feeder—scavenging from the seabeds of waterbodies for food—the Karimeen benefits from the availability of an abundance of nutrients, enabling it to grow quickly and thrive.

Notes on Cichlid Fishes of Malabar by N. P. Panikkar, a former Inspector of Fisheries in Travancore, details the reproduction, life history, and unique nest-making habits of the Karimeen. He explains how during breeding season, the Pearlspot pairs seek shallow, shaded areas to deposit their eggs on surfaces like stones, wood, coconut husks, or leaves submerged in less than three feet of water. They roughen smooth surfaces by biting them and clean the chosen area by removing dirt or vegetation. If the surface is too low, they excavate a cup-like depression in the ground. Both partners prepare the nest, and the process takes three to five days. This meticulous nesting behaviour not only highlights the species' adaptability, but also its instinctive resilience.

The fish also boasts unique anatomical features that set it apart. For instance, its anal fin, located at the rear end, is adorned with several spines—far more than the three or four typically found in other cichlids. Another evolutionary marker is its swim bladder structure, a trait shared only with the Paretroplus cichlids of Madagascar swimming 4,000 kms away. The membranous, gas-filled sac helps the fish maintain its buoyancy in water. No wonder Stewart called it a “creature that provides a direct link back to the most important event in the formation of Eurasia.”

The fish also boasts unique anatomical features that set it apart.

The same event is explained in Pranay Lal’s Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent, where his skillful recounting of the subcontinental separation helps link the Karimeen fish to Bengaluru’s late afternoon rains. The two are tied together by a historical event that is marked by the Palakkad Gap—a low, 30 km-mountain pass in Kerala’s Western Ghats. This geological feature was formed 88 million years ago when the Indian subcontinent separated from Madagascar: the same event that slowly transformed a branch of the ancient cichlid fish family into the Karimeen. The break in the ghats formed by the Palakkad gap actually allows the moist Arabian Sea winds to bring rain to Bengaluru, tying the city’s weather to an ancient geological period.

The Western Ghats' Palakkad Gap and Madagascar's matching Ranotsara Gap are twin escarpments that mark where the continents once joined. A fish, a city's rainfall, and a continent's fracture—all connected across millions of years.

The ‘Karimeen’ was first described by the German ichthyologist (a branch of zoology devoted to fish) Marcus Elieser Bloch in 1790, in the fourth volume of his 12-volume treatise on fish: Naturgeschichte der ausländischen Fische. Etroplus suratensis, the genus name of ‘Karimeen,’ originates from the Greek words ‘etron’ (belly) and ‘oplon’ (arms), referring to the spines on its anal fin. But the word suratensis in the genus name is surprising: it refers to the city of Surat, Gujarat, which was the ‘type locality’ of the fish–the place from where the specimen was probably shipped to Bloch.

The Madras Aquarium Report of 1921 also lists the Karimeen as a regional food source.

Although the Karimeen was officially declared the State Fish of Kerala only in 2010, its popularity predates this recognition. From books and movies to film songs and folklore, this ‘star’ fish is inextricably linked to Kerala’s cultural identity. For instance, these lines from a 1979 film song are a sort of a kitchen anthem for Malayalis: “Ayala porichathundu karimeen varuthathundu kodambuliyittu vecha nalla chemmeen kariyumundu” (There is mackerel fry and pearlspot fry, also prawns curry made with Malabar tamarind). Generations have passed, but the love for the song hasn’t ceased; it was remixed and re-released years later. Similarly, “Pennale pennale, karimeen kannale kannale” (Girl, oh girl with the Karimeen-like eyes) uses the fish as a simile for the beautiful eyes of a woman—one of many such cultural references.

The fish’s significance is reflected in historical records as well. Texts and documents from the colonial period frequently mention it. James Hornell, former Director of Fisheries, and N.P. Panikkar, Inspector of Fisheries in Travancore, extensively studied and wrote about the Pearlspot in the Madras Fisheries Bulletin, which was released in 1921.

Food historian Deepa G explains that scholars of that era often referred to the Karimeen as a common man’s fish in South India and Sri Lanka. “With the emergence of new research on diet, nutrition, and food consumption, the fish gained significant importance, eventually becoming Kerala’s signature fish,” she says. It was already a staple for communities living near mangroves, particularly those who relied on fishing for their livelihood. The Madras Aquarium Report of 1921 also lists the Karimeen as a regional food source.

Whether you're from Kerala or not, if you've tasted Karimeen, chances are you have a story to tell. For some, it’s the challenge of navigating its delicate bones, while for others, it’s a memory tied to the vibrant toddy shops of Kerala, where spicy Karimeen preparations are best enjoyed with a glass of freshly tapped palm wine. This fish is deeply woven into Kerala’s culinary fabric in more ways than one. In Kuttanad, there’s even a saying that a prospective groom must prove his worth by skillfully eating a Karimeen—leaving nothing but the bones behind.

But what gives the Karimeen its unique taste—the faint undertone of clay, a hint of earthiness, and a mild sweetness? According to marine biologist KK Vijayan, who served as the director of the Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (CIBA) for 15 years, it’s the backwater ecosystem. “Karimeen’s flavour profile largely depends on the water it inhabits. The backwater ecosystem, as we know, is ideal for it to thrive. The confluence of freshwater and seawater creates stress on the fish, forcing it to adapt. This stress triggers the production of antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which contribute to Karimeen’s distinctive flavour,” he explains.

The confluence of freshwater and seawater creates stress on the fish, forcing it to adapt. This stress triggers the production of antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which contribute to Karimeen’s distinctive flavour.

Interestingly, in an attempt to discover the best-tasting Karimeen, a 2024 study by the Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS) analysed both taste and nutritional differences in the fish from six locations. The study confirmed that the tastiest Karimeen comes from Kanjiracode in Kollam and Azheedoke in the Thrissur district. These findings are expected to bolster efforts to secure a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for Kanjiracode Karimeen.

Despite its cultural and economic importance, the fish faces existential threats. According to estimates by CIBA, as of 2020, Kerala produces around 2,000 tonnes of Pearlspot annually through farming, against a demand of 10,000 tonnes. “Wild stocks of fish, including Karimeen, have declined drastically. Over the past 10-15 years, marine catch has stagnated despite advancements in fishing technology,” says Vijayan. While specific data on the volume of Karimeen brought in from Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka to Kerala is not readily available, one thing is certain: without this exchange, the state cannot address the gap between the production and the high consumer demand for this fish.

It's true that the size has come down. However, that is because of continuous harvesting. We are not allowing the fish to grow to its full size.

The availability in the wild has been declining over the years due to a combination of environmental challenges, overfishing, and habitat degradation. The biological characteristics of the species, including low fecundity (number of eggs laid in a spawning season) and smaller clutch size (number of eggs laid in a single nesting attempt), are other factors. The reclamation of water bodies for urbanisation and other uses has further contributed to the Karimeen’s dwindling numbers.

Bhat warns that fish can be sensitive to certain pollutants, which means that a sudden change in water quality is bound to affect them. “The Pearlspot may be a hardy fish when compared to many others, but even it may not be immune to certain external factors. Our own bodies struggle to adjust to temperature changes that accompany each passing year and the impact on our physiology. It’s similar for the fish as well,” says Bhat.

Studies in the last few years echo these concerns, noting a drastic reduction in catch. One particular study that looked at data generated from the fishing grounds of the Vembanad Lake in 2012-13 found that even from this one source, the annual landings seem to have gone down to 135.28 tonnes from an earlier record of 1252 tonnes in 1969—and this was over 10 years ago. More recently, total inland production of Karimeen fell from 4644 tonnes in 2006-07 to 4194 tonnes in 2018-19.

In the Vembanad Lake study, local fishermen revealed that the average size of the fish in their catch has reduced substantially in the last decade. A little further away, in the Ashtamudi lake in Kollam district, the length of the Karimeen has reduced by 10 cm, according to a census conducted in 2022 by the aquatic biology department of Kerala University and Fisheries Department, jointly.

“It's true that the size has come down. However, that is because of continuous harvesting. We are not allowing the fish to grow to its full size. Within a year of hatching, they are harvested. If we wait for 2-3 years, the size will substantially increase,” says Bhat.

Aside from environmental stress, the population is also strained by particular fishing activities. Niyas, a fisherman from the Ernakulam district, explains that there are some who specifically target the Karimeen while it spawns. “A unique behaviour exhibited by the Karimeen is that it makes small holes in the riverbed to protect its eggs and fry, or the newly hatched fish. Once the hole is made, the male and female parents won’t abandon the area. A section of fishermen take advantage of this, walking over the river bed till they feel the holes with their feet and catch the fish with their hands. Sometimes they use a ring-like structure and place it over the hole to trap the fish.” With parent fish being targeted in this manner, the impact on the overall population is inevitable.

Dr. Vikas PA, a subject matter expert at Krishi Vigyan Kendra, explains: “It’s in the fish’s nature to stay around these holes and fan water over the eggs to keep them oxygenated while protecting them from predators. But this makes it easier for people to catch them. Exploiting this method can cause a decline in the overall numbers of the fish.”

People who overfish and exhaust the fish in their locality turn to other areas at night to fish for Karimeen.

No less problematic is the illegal trading of the fingerlings, most of which don’t even survive the exchange. Most fisherfolk are against catching fingerlings—the tiny, weeks-old young of the fish. This directly cuts into the number of young fish that can grow and reproduce. “Even if I accidentally catch them, I let them go. But some people keep and sell them for Rs. 10 or Rs. 20 a piece,” says Arun. People who overfish and exhaust the fish in their locality turn to other areas at night to fish for Karimeen.

The destruction of mangroves in the state has been tough on the species. In the last three decades, over 90% of mangroves in Kerala have been destroyed; from a vast 700 sq. km in the 1980s, the mangrove cover is down to a measly 17.82 sq. km, as per a 2020 study. These marshy regions serve as critical breeding grounds for the fish, and their drastic disappearance has reduced safe spaces for laying eggs. “Mangrove roots, once ideal for hatchlings, have been replaced by less suitable sludge, where young fish cannot survive. Changing rain patterns, particularly summer rains, and fluctuating salinity levels during June and July further disrupt the fish’s habitat,” says Dr Vikas.

Climate change and fluctuating water quality pose additional threats. “Our backwaters are in a poor condition. Many have become shallow due to siltation and the lack of tidal activity. Human activity—particularly urbanisation—has significantly degraded these ecosystems. Rainwater washes pollutants into rivers, reducing oxygen levels and causing fish mortality. Climate change has also altered water temperatures and breeding behaviors,” says Vijayan.

Bhat elaborates on the severity of the situation, drawing attention to the disastrous consequences of industrial waste. “The Periyar River, which feeds into the backwaters, is lined with industries that discharge untreated waste into the water. Over the past 20–30 years, the Kochi backwaters have shrunk considerably due to encroachment, disrupting the natural flow of freshwater and further degrading water quality.”

An unexpected challenge to the Karimeen’s survival is from the Tilapia, a highly fecund and easily bred fish that is outdoing it. Invasive Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) variants, known for their resilience, adaptability, and rapid growth, have become a preferred choice for farmers.

This hardy and cost-effective alternative actually threatens the Karimeen’s prospects in Kerala’s aquaculture. In fact, as of 2022, the total Tilapia production in the country was estimated to be about 70,000 tonnes; of this, 30,000 tonnes came from aquaculture alone. This large proliferation comes from the fact that even though Tilapia was only introduced to Indian waters decades ago, the fish has naturalised quickly, adapting and breeding in large numbers. The catch percentage of the Tilapia increased from 6.7% to 85.9% in the decade from 2008 to 2018. In the Kozhikode district of Kerala, Tilapia is now the most cultivated fish.

Tilapia is sometimes mistaken for Karimeen—both fish, after all, belong to the same Cichlidae family. Medium-sized Tilapia (300g–400g) can closely resemble Karimeen, and some restaurants have even substituted Tilapia for Karimeen. Vikas notes, “Some unscrupulous sellers may try to pass off Tilapia as Karimeen, especially to those unfamiliar with the size and taste differences.”

Medium-sized Tilapia (300g–400g) can closely resemble Karimeen, and some restaurants have even substituted Tilapia for Karimeen.

But that’s not all: the Tilapia is an invasive species, which are generally considered harmful to the natural habit into which they’re introduced. They can also feed on natural resources as well as the young and eggs of native species of a habitat, like the Karimeen.

Given these challenges, large-scale breeding remains uncommon in Kerala. “While some individuals collect eggs from breeding grounds and transfer them to smaller water bodies, systematic, large-scale breeding is not widely practiced,” notes Bhat.

Driven by the uncertainties of fishing, Karimeen farming in Kerala can be best described as an ‘emerging interest’: the fish are often bred in ponds, or cages in open waters.

“Water quality is vital—if it deteriorates or the acidity changes, fish can die. Oxygen levels must remain stable, but we rely on river water, which is sometimes polluted.

The controlled culturing of Karimeen requires a multifaceted approach. Hatcheries can regulate breeding and ensure fish are reared in controlled conditions, while the desilting of canals, restoration of tidal flow, and reintroduction of hatchery-bred juveniles into the wild could help replenish stocks.

“Aquaculture serves both conservation and commercial interests. It reduces overfishing in the wild, even if broodstock is sourced from nature,” says Bhat. He is referring to the pool of parent fish that serve as the genetic foundation to breed further fish. However, he warns of the environmental risks of large-scale commercial farming, emphasising the need for sustainable practices.

“Environmental, economic, and ecological consequences are inevitable—water pollution, disease transmission, and ecosystem degradation, for instance. However, these risks arise primarily when aquaculture is practiced on a large scale, which is not yet the case in Kerala. But as we expand, it is crucial to adopt sustainable practices after carefully weighing the pros and cons,” says Bhat.

Shibu, a hatchery owner in Puthukkad, ventured into Karimeen farming in 2018 after attending a Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) course. He now produces over 1.5 lakh Karimeen fry annually, but his success is strongly dependent on water quality and environmental factors.

“Preparing the pond is crucial. We need to eliminate weed fish, balance the water’s pH, and use lime to condition it. Only after the pond is ready do we introduce the brood fish. It takes about 45 days to get the seed, which is then moved to a hapa and fed thrice daily,” Shibu explains. A hapa is a rectangular net enclosure placed over waterbodies to hold fish.

Farmers purchase these seeds to rear fish, but challenges persist. “Water quality is vital—if it deteriorates or the acidity changes, fish can die. Oxygen levels must remain stable, but we rely on river water, which is sometimes polluted. We also deal with predators like cormorants and otters,” he says.

Marketing is another major hurdle. “We have the seed stock but struggle to sell it. Social media and newspaper ads help, but the support of state fisheries and centralised branding could make a big difference,” he says. With Kerala’s Karimeen demand still heavily reliant on wild catches, Shibu believes more people need to take up farming to bridge the gap sustainably.

To make Karimeen-centric aquaculture viable, Kerala needs comprehensive programs for seed production, feed development, and farming technology. Small-scale backyard hatcheries, supported by the government, could engage communities living near backwaters, suggests Vijayan.

Despite experimental breeding efforts by institutions like the Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (CIBA), the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), and the Kerala Fisheries College, large-scale commercial hatcheries have yet to materialise. “The larvae produced in these hatcheries are too few to support widespread aquaculture. For aquaculture to succeed, we need commercial hatcheries capable of producing seeds in significant quantities,” adds Bhat.

On a positive note, KUFOS recently proposed a genome editing mission to enhance Pearlspot production. Currently, fish farmers in Kerala face challenges such as sourcing broodstock from the wild, breeding them in uncontrolled environments, and releasing fingerlings into aquaculture ponds, only to see the fish reach a modest weight of 300–400 gm in a year. This pales in comparison to the maximum reported weight of Karimeen caught from the Vembanad Lake, which stands at 1.2 kg.

The KUFOS’ genome editing mission aims at revolutionising aquaculture, much like the GIFT initiative did decades ago. By targeting the genetic factors that inhibit faster growth rates, the project could enhance breeding and seed production of the Pearlspot. Achieving higher body weights at an accelerated rate would significantly benefit farmers, as the Karimeen commands a premium in the market compared to Tilapia.

To farm the Karimeen sustainably, Kerala needs to address several technical, economic and social challenges. Farmers must adopt scientific practices to make ventures profitable and ecologically sound. “Economic viability is a must. Farmers should receive reasonable prices for their produce,” says Bhat.

But the list of measures doesn’t end there; management practices are crucial, too. “Proper pond preparation, stocking, feeding, water quality maintenance, disease prevention, and humane harvesting are critical,” he adds.

What Kerala—and its star fish—needs is a mission program.

Urgent steps must be taken to adopt better aquaculture practices. “The Pearlspot grows slowly—it can take up to a year to reach maturity. For farming to be profitable, we need technology that shortens this period to six months,” says Vijayan. Mixed farming, where the Karimeen is reared with species like Flathead Grey Mullet (Thirutha), Milk Fish (Poomeen), or shrimp, could help farmers earn multiple incomes. “Composite farming may be an old concept, but it is still highly relevant,” says Vijayan.

While the Karimeen has unique traits like parenting—the parent fish’s effort to protect the young after spawning—breeding control remains a challenge. Pairwise breeding is essential to maintain quality seed, but current practices often lead to inbreeding. Generally, this could affect the fecundity, growth rate and survival of the young; it could even encourage illness and deformity. “The Karimeen produces an average of 1,000 eggs across one breeding season—far fewer than tiger shrimp, which can lay over a million eggs. But Kerala lacks commercial hatcheries with controlled seed production. We need hatcheries where male and female fish are kept under controlled conditions to breed, with larvae reared and sold to farmers,” Vijayan emphasises.

What Kerala—and its star fish—needs is a mission program. There are certainly standalone schemes, like a boost from the Multispecies Aquaculture Complex (MAC) for Karimeen farming in the Kochi complex, or broader programmes like the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana’ (PMMSY) that aim at enhancing inland fisheries at large. The state has resources and manpower, but they aren’t connected by a unified vision. CIBA has successfully developed pair breeding technology for the Pearlspot, enabling cost-effective modular hatcheries to produce quality seeds in required quantities and timelines. While the institution is ready to offer scientific and technological support, the authorities have to create a roadmap to improve the sector. It requires a comprehensive plan, financial assistance, and coordinated efforts between the scientific community and the government.

A collaborative approach that integrates scientific innovation, government support, and community participation is the need of the hour. Empowering farmers with technology and promoting ethical practices will not only boost the local economy but also preserve ecological balance. Such efforts will ensure that this cherished species continues to thrive for generations to come, while also enabling people like Arun to follow in his father’s footsteps and once again rely on the Karimeen for their livelihood.

Edited by Binu Karunakaran, Anushka Mukherjee, and Neerja Deodhar

Produced by Nevin Thomas and Neerja Deodhar

Cover art by Prabhakaran S

All photos by Joseph Rahul

Also read:

The perilous future of Kashmir’s once-abundant trout

Omega-3 fatty acids: The hidden costs of ‘health’ to our seas

The virus, though deadly, is unlikely to lead to a pandemic. Yet in the absence of a ready vaccine, being cautious is important

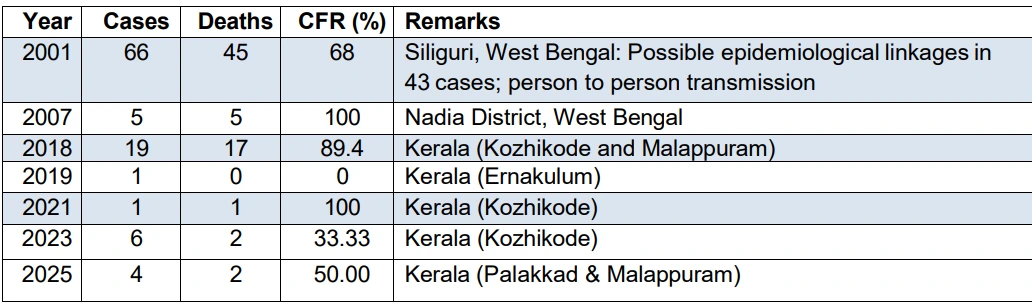

Late in December 2025, two healthcare workers in West Bengal’s North 24 Parganas district developed symptoms of a severe viral infection. On 13 January, the National Institute of Virology’s laboratory confirmed that these were indeed the Nipah virus. Though rare, the virus invokes deep fear globally; several of India’s neighbours have already started screening Indian visitors as a precautionary measure. Why does the virus induce fear, and what is its true risk potential?

The fear surrounding the infection stems from two main causes: the lack of a licensed treatment or vaccine, and the difficulty in early diagnosis.

The Nipah virus is a zoonotic virus, i.e. it is transmitted to humans through animals. The virus can jump to humans in two ways: through contact with the saliva or other bodily fluids of the natural hosts of the virus like fruit bats or flying foxes, or through intermediary hosts (usually pigs or other humans) who have been infected. The virus, first identified in Malaysia in 1999, has only affected five countries so far, all from Southeast Asia. India has had 8 outbreaks over the past quarter century, including the latest one. Globally, there have been 754 cases and over 435 deaths since the virus was first identified.

The infection has an incubation period of three to 14 days—this is the time interval between the virus’s entry in the body and the first appearance of recognisable symptoms. While some people may remain asymptomatic, most show at least mild symptoms like fever along with symptoms involving the brain (such as headache or confusion), and/or the lungs (such as difficulty breathing or cough). Patients with mild symptoms can make a full recovery. However, if the infection becomes severe, the symptoms become neurological, and indicate encephalitis—that is, a swelling of the brain. Encephalitis and seizures usually progress to a coma in 24 to 48 hours. Patients with severe infections are also likelier to spread the infection.

For those who survive, recovery is slow, and for some, neurological symptoms persist for years because of the way the infection impacts brain cells. This makes rehabilitative care critical for patients on the mend. The case fatality ratio (CFR), that is the percentage of patients who will die, varies widely. The WHO places it in the range of 40% to 75%, but India has reported CFRs both below and above these figures. In the absence of any known cure, treatment for patients is limited to intensive supportive care, including rest, hydration, and treatment of symptoms as they occur. Still, hospitalisation is important to monitor the way the disease affects a patient’s organs, and to control transmission.

The fear surrounding the infection stems from two main causes: the lack of a licensed treatment or vaccine, and the difficulty in early diagnosis. Though a vaccine is under trial, and some drugs have worked in limited capacities, none of these are officially approved by the WHO yet. Early diagnosis is difficult for many reasons. Firstly, the symptoms of mild infection are very similar to a regular viral infection. Secondly, the testing process is sophisticated. This leaves only a handful of institutes in the country equipped to test for Nipah virus. Of them, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has authorised only one institute—National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Pune to confirm cases. This is because NIV Pune is the only Bio-Safety Level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory in the country. The biosafety level certification is also important to contain the samples and ensure that biowaste is disposed of safely after testing.

Also read: How drug-resistant tuberculosis is bringing life to a halt in India

In India, only bat-to-human and human-to-human transmissions have been identified. Bat-to-human transmissions are generally caused by consumption of food that is contaminated by the blood, urine, or saliva of fruit bats. In West Bengal, especially, outbreaks have been linked to the consumption of raw palm date sap (Khejur Ras) and coincide with the harvest season for the sap (December to May).

The precaution, then, is to thoroughly wash and peel fruits before consumption, especially if one lives near areas with a bat population. If a fruit has bite marks, discard it. And in the case of palm date sap, boiling it to form nolen gur or patali gur before consumption can ensure safety.

The Nipah virus is not airborne; human-to-human transmission happens through contact with bodily fluids or contaminated bodily tissue. Contaminated tissues can refer to tissues collected during testing or tissues discarded during surgical processes while treating any organs affected by the virus. This places caregivers, healthcare workers, and even those conducting burial/funeral rituals at risk. Preventative measures include assigning patients to single rooms, wearing protective gear like gloves while caring for or visiting patients, and washing hands after. Hospitals and laboratories also have to follow strict procedures for handling and disposing tissues to prevent transmission.

The virus, though deadly, travels in a very tight circle and has been vigilantly managed.

That said, the Nipah virus is unlikely to lead to a pandemic. It typically has a reproduction number of less than 1. This figure indicates the expected number of secondary infections stemming from a primary infection, signalling that its tendency for human-to-human transmissions is low.

On 26 January, 2026, India notified the WHO about the two Nipah virus positive cases. They also confirmed, after testing 190 contacts for the virus, that no further cases have been detected. Out of the two patients, the second case has shown clinical improvement, while the first case remains under critical care.

The virus, though deadly, travels in a very tight circle and has been vigilantly managed. Outbreaks have been linked to habitat disruption of the host bats, and are likely to happen again in areas where urban spaces are replacing woodlands. Even as vaccines are being developed, being vigilant, maintaining hygiene, and focusing on prevention remains the best cure.

Also read: Add crisis to cart: Why instant delivery and antibiotics don't mix

Features like tidy lawns may be aesthetically pleasing, but they narrow the sustainability and full potential of urban gardens

Editor's Note: The planet we inherited as children is not the planet we will someday bid goodbye to. The orchestral call of cicadas in the evenings, the coinciding arrival of the monsoon with the start of the school year, and the predictability of natural cycles—things we thought to be unchanging are now at risk. An altered climate, declining biodiversity and warming oceans aren’t distant realities presented in news headlines; they affect us all in seen and unseen ways. In ‘Converging Currents’, marine conservationist and science communicator Phalguni Ranjan explores how the fine threads connecting people and nature are transforming with a changing planet.

Gardens are wonderful little spaces. They offer tranquillity, fragrance, shade, a visual delight, and a patch of green relief from a world of asphalt, concrete, and honking horns—in short, a quiet retreat.

But they do so much more than that.

These green spaces can quietly nudge the trajectory of urban biodiversity, sometimes towards resilience, sometimes towards decline. Urban gardens—be they home gardens, community parks, or botanical gardens—also provide critical ecosystem services.

Home gardens, or domestic gardens, make up a significant component of urban green spaces. They have been an integral part of household farming, animal rearing, and local food systems for centuries: used to rear and manage livestock, grow food for family consumption, and provide food security during and after crisis situations. More recently, they have become integral parts of city homes, taking root on balconies, terraces, in buckets and bags, and on windowsills. Their size, location, and purpose have evolved over time, but their ecological relevance persists—now, more than ever.

Home gardens are believed to be one of the oldest forms of cultivation alongside shifting cultivation. In fact, growing food on small, home-adjacent plots of land is believed to be how organised cultivation started, a practice once widespread across the tropics. Possibly the oldest evidence of this dates back to the 7th millennium BCE. Records from Kerala trace back 4,000 years, with significant mentions from southern India, particularly in the 1800s.

For centuries, they served as repositories of plant genetic diversity,and food security.

Traditional home gardens were—and still are—defined by the vertical stratification of trees, shrubs, crops, and herbs: the tall canopy of timber trees like teak blended into a mid-height layer of fruit-bearing trees like jackfruit and mango, followed by a ground layer of medicinal herbs and vegetables that sustained families and livestock.

This well-thought out, minimally managed, holistic, crop-tree-livestock system fit quite well within the rural farming setup, much before commercial monoculture farming took root in the country. One would assume ‘agriculture’ to be a rural concept involving large farms, but today’s home gardens are a prominent form of urban agriculture—kitchen, terrace, windowsill or otherwise—fuelled by hobby and a desire to eat clean.

Historically, in India and the tropical world, gardens were practical, intimate spaces close to home: supplementary, utilitarian, and deeply entangled with daily life. For centuries, they served as repositories of plant genetic diversity, and food security. They were a haven for pollinators, slowly allowing the adaptation, domestication, and diversification of plants to local ecological conditions.

These ecologically sound units sustained their own water cycles and pest control through complex species interactions, in a unique way that only naturally propagated systems can. Families, relying on generations of traditional ecological knowledge, closely managed this well-balanced system with minimal input; cultivating vegetables, fruit trees, herbs, medicinal plants, and flowers that fed and supported people and biodiversity, and reflected local climate and culture.

Also read: Climate change in my cup: Why India’s cocoa and coffee production is at risk

Plants are green, but not all greenery behaves the same way, ecologically speaking.

Worldwide, the shift from food-bearing native home gardens to clipped lawns and ornamental beds has reshaped how flora, fauna, and people coexist. While cities desperately need green patches for pollinators, clean air, and cooler temperatures, some gardens—specifically politely mowed lawns with sculpted hedges and ornamental plants—may be working against the very ecological health they appear to support.

Traditional home gardens did not disappear overnight. Their gradual decline can be tied to a multitude of factors compounding over the last couple of centuries or so.

Functional diversity quietly gave way to visual appeal as ‘tidy’ became the cultural norm—form over function, aesthetics over sustainability.

Globally, industrialisation and urbanisation changed lifestyles, aspirations, and economic situations. Over time, increased access to cities, education, media, and the internet reshaped aspirations, especially among the youth, resulting in smaller rural households, reduced home food production, and a preference for purchased food and non-farm livelihoods. Socio-cultural influences within a changing society increased investment in gardens: introducing new species and techniques to make them more ‘aesthetic’. But this also caused a loss of traditional knowledge, reduced use of medicinal plants, declining interest in tending to vegetable gardens, and an ageing population unable to manage these spaces.

Rapid urbanisation and the growing demand for intensive, large-scale agriculture further reduced available plot sizes, detaching homes from cultivable land. As cities expanded vertically and horizontally, space once used for vegetables and herbs was replaced by buildings, parking, or decorative green patches.

Globally, under Western influence, gardens increasingly became markers of leisure and status. In 17th century France, manicured lawns became symbols of political power and control over nature. Neatly trimmed lawns, hedges, and exotic ornamentals signalled beauty, tidiness, and affluence in England—as only the wealthy could afford labour to keep the grass appropriately prim and trimmed.

At this time in India, many gardens still reflected the Mughal concept of the four-sectioned gardens (charbagh). These elite gardens combined architectural elements like water fountains and canals with shade-giving trees to create cool microclimates symbolising rest, leisure, and luxury.

Eventually, the British transplanted their lawns in India as an extended projection of affluence, sophistication, and control. The grasses brought in were unsuited to this climate and ecology, and to this day, continue to soak up large quantities of water while offering minimal ecological function.

Functional diversity quietly gave way to visual appeal as ‘tidy’ became the cultural norm—form over function, aesthetics over sustainability. Recreational public parks and botanical gardens expanded, and native grasslands and gardens faded away.

The British left, but the legacy of the lawns continued.

Also read: Omega-3 fatty acids: The hidden costs of ‘health’ to our seas

Cultivated and managed largely without chemical inputs, home gardens, with diverse trees, shrubs, herbs, and crops closely resembled natural forest patches in structure and function. Their benefits were manifold: crops fed families and livestock, livestock provided manure and products like dairy or wool, Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP) from trees and medicinal herbs supplemented income, and timber and fuelwood supplemented domestic requirements. Surplus from the fruit trees was shared socially, strengthening community ties and larger home gardens also offered seasonal employment opportunities.

This agroforestry system required minimal financial investment, making it accessible for most people. Still prevalent in several parts of India today, including Kerala and parts of northeast India, contemporary home gardens also offer multiple benefits like tranquil spaces to connect with nature, carbon sequestration, groundwater recharge, conserving a genetic diversity of plants, and a good old serotonin boost.

Home gardens can support homes and families significantly—contributing 25-85% to household food needs in Ethiopia, 55-79 kg of vegetables per person annually in Bangladesh, and upto 24% of the monthly income in parts of Indonesia—highlighting their potential role in achieving food, economic, and nutritional security. An average-sized home garden can provide economic benefits of more than Rs. 18,000 annually through yield, with even small gardens sequestering significant amounts of carbon in the soil and plant biomass.

An average-sized home garden can provide economic benefits of more than Rs. 18,000 annually through yield, with even small gardens sequestering significant amounts of carbon in the soil and plant biomass.

Studies state that home gardens can also contribute towards six of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), including 1 (No Poverty), 2 (Zero Hunger), 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), 13 (Climate Action) and 15 (Life on Land).

Urban green spaces or gardens—comprising home gardens, parks, or forests within a city—provide substantial ecosystem services, contributing significantly to air purification and climate regulation. These green patches can also supplement green corridors within a city. Green corridors—connected patches of natural vegetation and greenery—allow movement and genetic exchange between wildlife populations, and provide crucial support for pollinators. They could be interconnected networks of tree-lined streets and walkways, parks, gardens, and any other patches of greenery that act as ‘stepping stones’ to connect larger green areas.

Even if this ‘corridor’ is spaced out by infrastructure, the patches can still act as critical connectivity points for pollinators; a bit like pitstops for refuelling. They can also help mitigate the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, where cities experience warmer temperatures than surrounding rural areas, mainly due to low green cover and more heat-absorbing materials like concrete.

Also read: Bugging out: Why declining insect populations in India spell doom for agriculture

Urbanisation disrupts the natural environment, introducing stressors like heat, pollution and fragmentation of green spaces, ultimately disrupting the interaction between pollinators and plants: impacting their behaviour, biology, and evolutionary pathways. Around 87% of the world’s flowering plants, and many major crops are pollinated by animals, and pollinator declines can threaten food security and biodiversity.

However, green spaces within cities can help offset this; they can harbour and support a greater and healthier diversity of pollinators than intensively-managed agricultural lands. As heavily managed agricultural plots are often chemically managed and focus on one key crop (monoculture), the fields lack the plant diversity pollinators need to thrive.

How we manage our home gardens affects soil characteristics, invertebrate interactions, and overall ecosystem function. Frequent and intensive mowing can negatively affect the presence of bees, ants, wasps, cicadas, butterflies, wasps, and other bugs, especially winged insects (many, pollinators) while creating favourable conditions for common pests to thrive.

It turns out, grass-free gardens with predominantly native species can actually host a healthier number and diversity of insects than grassy lawns.

The solution? Mow only the surface layer, and no more than twice or thrice a year—a concept echoed by multiple studies. A significant reduction in mowing improves plant diversity in gardens. Allowing plants to grow to variable heights provides structural complexity and space for insects to live, feed, thrive in; structure otherwise lost in uniformly mowed lawns. Higher plant diversity further contributes towards healthier soil: biological activity, moisture, and organic and microbial carbon content. It supports associated fauna like earthworms that need varied root structures, nutrients, rich organic content, and healthy microhabitats within the soil to thrive.

Weeds are another component of this complex system: unwanted by definition and often rooted out. However, it is possible that de-weeding gardens may do more harm than good, though there is limited evidence on this. Weeds can offer organic content for the soil, contain rhizobacteria that can help improve the nutrient profile of the soil, and exhibit pest-controlling properties. Even despite the thin evidence in this regard, there is no denying that traditional home gardens did have weeds growing alongside everything else. Interestingly, several medicinal plants commonly used in local herbal medicine and Ayurveda are conventionally weeds that grow almost everywhere.

Now, you might wonder: how will a small balcony garden of potted plants support all this biodiversity? It turns out, grass-free gardens with predominantly native species can actually host a healthier number and diversity of insects than grassy lawns. Furthermore, the grasses in circulation today are not all native to India; many were introduced here, some have been around long enough to become naturalised—able to grow and spread on their own in the local environment—and they consume large quantities of water.

Native plants belong to the region, while non-native or ‘introduced’ plants are introduced from elsewhere. Invasive species are non-native species that out-compete native species, cause harm, and spread aggressively (like Lantana). However, an exotic species is typically harmless, but still has an edge in terms of survival and propagation. Many of the ornamental indoor plants we find in nurseries today are exotic.

If done right, residential gardens can serve as pollinator hotspots, contributing significantly towards urban biodiversity. Native plants attract and support more pollinator species—more ‘specialist’ and native insects—than exotic plants do. Native herbivorous insects also show a clear preference for native plants to feed on.

Exotic flowers, on the other hand, are visited by generalist pollinators—those without a plant preference—and also contribute towards overall green cover, providing alternatives for some pollinators especially in the temporary absence of native flowers.

However, some exotic plants can compete with native species as they are hardier and more robust, and do not easily succumb to urban pressures of heat, pollution, water scarcity, and habitat isolation the way native species might.

However, some exotic plants can compete with native species as they are hardier and more robust, and do not easily succumb to urban pressures of heat, pollution, water scarcity, and habitat isolation the way native species might. Pollinators, smaller animals and other plants associated with native flora are put at risk when the native plants are replaced completely, upsetting a delicate balance that is critical for the ecosystem. However, it is important to note that while pollinators may not visit exotic flowers as much, these plants still do offer services: nesting and shelter spots, and green cover. A native-exotic cluster could also be more resilient, with the hardier exotics buffering the natives against environmental extremes.

However, in an environment where exotic species already exist because of us, the exotic vs native debate is rendered moot. We did this perhaps unknowingly, and—ironically, continue doing it—often, somewhat knowingly.

India is home to an estimated 45,000 known plant species, making up around 7% of the world’s known plant species, of which approximately 28% are endemic—i.e., found only here.

According to Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) estimates, urban green cover has decreased by 23% over the past decade, and green spaces only make up around 2% of all urban land area.

The Urban Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) guidelines, 2014 recommend 10-12 m² of open space per person in cities, including green spaces. The World Health Organization recommends at least 9 m² and ideally 50 m² of green space per person as an indicator for sustainable cities. Sadly (and predictably), many of our major Indian cities fall dramatically short of that.

Chennai offers only 0.81 m² of open public space per person, Kolkata offers 0.67 m2, and Ahmedabad a mere 0.5 m2. One might argue that these cities boast large landmark gardens and parks, but their area relative to the population and the city’s area is insufficient to meet the URDPFI or WHO standards.

India’s population is expected to double by 2050, with 50% of us living in urban areas. Whether cities adapt to become biodiversity refuges or concrete deserts depends, to an extent, on choices we make today.

Yes, popular indoor plants are easier and low maintenance, but in the long term, planting marigolds,aparajita(butterfly pea), native hibiscus, and jasmine could be more fufilling, with the colours, fragrance, and the birds that come in along with the buzzing bugs.

Rising food prices, environmental concerns, and health awareness have sparked a modest revival of urban kitchen and terrace gardening in large cities. Terrace farming (urban agriculture) is catching on now, and some estimates suggest that converting even 5-10% of a city (i.e. rooftops, terraces, gardens etc.) to grow produce could supplement the vegetable requirements of the people.

While most urban development plans take into consideration public parks, botanical gardens, and other green spaces, the role of home gardens is largely neglected. Even a small balcony can function as a productive, biodiverse haven if done right. Reimagining home gardens as ‘stepping stones’ in a larger ecological corridor could help establish green connectivity in cities, contributing towards biodiversity conservation and urban sustainability.

Is cultivating a complex balcony garden logistically feasible? Not really.

But, is it impossible? Not in this age of innovative solutions and quintessential Indian jugaad.

***

Many of my preferred ‘low maintenance’ balcony plants are exotic, and almost none are flowering plants—a realisation that stumped me. Peace lilies, spider plants, Birkin (Philodendron), and some varieties of the pretty aglaonema and the never-dying (this should have been a clue) money plant (Epipremnum sp. or Pothos) are not native to India!

Nurseries supply these plants abundantly: they are cheap, easier to maintain than flowering natives, and so many of us choose this convenience—because, let’s face it, gardening takes time and ‘low maintenance’ plants fit in with our busy lives.

But, at the home-level, small changes like incorporating more native flowering plants, planting some vegetables, and reducing chemical inputs can help support more biodiversity. It boils down to choice, as this is one of those few good-for-the-environment things that can also be an absolute delight for the soul; something that needs us to build and nurture rather than reduce (like energy, water usage) to benefit the environment.

Yes, popular indoor plants are easier and low maintenance, but in the long term, planting marigolds, aparajita (butterfly pea), native hibiscus, and jasmine could be more fufilling, with the colours, fragrance, and the birds that come in along with the buzzing bugs.

So, let some of those weeds and native flora creep back in, and let your garden grow just a little wild (in looks and function), as it was always meant to—enough for it to support the bugs, birds, and biodiversity.

Some lists and additional information: lists of common invasives, invasives of Kerala, succulents of India, flowers of India, native plants of India.

Edited by Anushka Mukherjee and Neerja Deodhar

Artwork by Radha Pennathur, Communication Designer & Illustrator

{{quiz}}

Fibre is essential for everyday functioning, playing a role in waste expulsion and the production of chemicals like neurotransmitters

We like to think that the human body is self-sufficient—that it single-handedly manages a diverse range of functions reliably, regularly, and (for most of us) flawlessly. In reality, it chooses efficiency over self-sufficiency. When it is too resource-intensive to develop something, it simply outsources that function. For example, instead of struggling to produce short-chain fatty acids, it houses and feeds bacteria that can produce them instead. We’re reliant on this system now; bacterial populations are responsible for crucial functions like immune responses as well as access to essential nutrients.

Most of the human body’s bacterial population resides in the large intestine, especially in the colon. Most of the food we eat first reaches the small intestine, where its constituent nutrients get absorbed. But, there is usually one major component of food that passes through the small intestine and reaches the large intestine undigested: fibre. Our gut bacteria ferment these fibres to produce useful byproducts, including vitamins and short-chain fatty acids.

A study from 2023 revealed that 7 out of 10 Indians are not consuming the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of fibre, which is about 30 gm for adult women, and 40 gm for adult men. Simultaneously, according to a government report from 2025, protein consumption has picked up, and even crossed the RDA. A 2024 American study has directly linked high-protein diets with changes in the population of the gut microbiome (or microbe communities). What does this mean for our health?

According to the 2025 government report, the increase in protein intake has been accompanied by a fall in the total caloric intake, in both rural and urban India. If the total number of calories being consumed is falling, and the total protein consumption is increasing, we can infer that animal proteins like dairy and meat are replacing plant proteins. This is because plant sources are less protein-dense than animal sources like dairy or meat, and one would have to consume more calories to reach the same protein intake.

A study from 2023 revealed that 7 out of 10 Indians are not consuming the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of fibre, which is about 30 gm for adult women, and 40 gm for adult men.

This replacement comes at a cost—the fibre component of the diet (only present in plant foods) gets replaced by excess protein and fat. The gut microbiome is impacted in two ways: the effect of too little fibre, and that of too much protein.

Also read: Do proteins keep us fuller and less hungry than carbs and fats?

The lack of adequate fibre will naturally prevent the bacteria from fermenting it and releasing helpful byproducts, including short chain fatty acids and neurotransmitters like dopamine. It’s not just the fermentation that is useful, though. Even the unfermentable fibres in the large intestine play a crucial role: smoothening the passage of stools. Emerging science suggests that low-fibre diets could also permanently reduce gut bacterial diversity (never a good sign) and even result in the starved bacteria eating our colonic lining, thus compromising the protective mucosal layer that keeps microbes at a safe distance while allowing nutrients to pass through.

As for protein, the gut microbes are used to dealing with some undigested protein regularly. These amino acids can be fermented into good byproducts like short chain fatty acids or harmful ones like ammonia and hydrogen sulphide. The nature of the byproduct depends on the quantity as well as the type of amino acids that reach the colon.

Also read: The ‘right time’ to eat protein: Little and often, rather than in one meal

How much undigested protein reaches the colon roughly depends on two factors. First, the amount of protein consumed in one go. The body can only digest limited protein in one go and passes ahead excess protein to the large intestine. Second, the protein source: this determines how easily the body can digest it. Animal proteins are easier for the body to digest, so less undigested animal proteins will reach the large intestine.

However, plant proteins have been documented to be gentler on the gut when they do reach the large intestine undigested, possibly because they inherently have more fibre. In fact, across studies, plant proteins are not associated with any negative byproducts of fermentation. But overall, excess protein fermentation in the colon has been associated with intestinal diseases—such as inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer—as well as metabolic diseases.

A high rate of protein fermentation has also been linked to reduced non-digestible carbohydrate (i.e. fibre) availability in the large intestine. This is one of the reasons why high-protein diets change the gut microbiome—undigested protein outcompetes the undigested carbohydrate, and the bacterial population adjusts to include more protein-digesting bacteria. This directly impacts the diversity of gut microbes.

Also read: More isn’t always better: Are you overdosing on protein?

Now, there is considerable variation in the microbial species found in the guts of different individuals, but they still fall within five dominant phyla (phylum being the third broadest categorisation of organisms). The composition of the microbiome also changes with alterations in diet and lifestyle. But roughly, there is an understanding that a healthy gut will have species from the dominant phyla despite the internal differences. Beyond helping with digestion, these microbes form a critical aspect of the body’s immune response, and less microbial diversity makes the body more vulnerable to a slew of health issues. There is historical data strongly suggesting that industrialisation and a shift towards westernised diets decreases gut microbial diversity.

For the gut to flourish, the conversation around nutrition must make some space for fibre, not as a competitor of protein, but as its companion.

The simplest way to ensure gut health, of course, is to actively incorporate fibre in one’s diet. Similarly, incorporate diverse protein sources. Microbial composition changes with the source of protein too—eggs, fish, dairy, and legumes all change the bacterial makeup of the gut. For the gut to flourish, the conversation around nutrition must make some space for fibre, not as a competitor of protein, but as its companion.

Slider Image: Green chickpeas by Jorge Royan by Wikimedia Commons

{{quiz}}

What if we see weeds less as intruders, and more as indicators of soil health and sources of nutrition?

Editor's note: Even before its current status as a nutrient-rich superfood, ragi has been a crucial chapter in the history of Indian agriculture. Finger millet, as it is commonly known, has been a true friend of the farmer and consumer thanks to its climate resilience and ability to miraculously grow in unfavourable conditions. As we look towards an uncertain, possibly food-insecure future, the importance of ragi as a reliable crop cannot be understated. In this series, the Good Food Movement explains why the millet deserves space on our farms and dinner plates. Alongside an ongoing video documentation of what it takes to grow ragi, this series will delve into the related concerns of intercropping, cover crops and how ragi fares compared to other grains.

On most farms, weeds are treated as intruders—uprooted, sprayed over, or suppressed with chemical weedicides. But in rainfed agrarian ecosystems, especially those growing millets like ragi, weeds have long been something else entirely: food, medicine, fodder, and indicators of soil health.

As the Good Food Movement experiments with growing ragi on a two-acre plot in Tiptur, Karnataka, we examine firsthand what it means to deweed without herbicides, and more importantly, how we can change the way we think about weeds in the first place.

In Kannada, the word for weed is kale. The adjective ‘kalegattirodu’ roughly translates to the glow or beauty that comes from being expressed. Historically, weeds were not a problem to be erased, but a presence that was allowed to express itself. Farmers recognised which plants could stay, which needed thinning, and which could be harvested for the kitchen or livestock.

On traditional ragi plots, especially rainfed ones, many weeds are seasonal and edible.“Weeds were never thought of as a nuisance. They were a part of the earth,” says environmentalist Muralidhar Gungaramale, who has extensively studied local, edible weeds and is working to preserve this knowledge. Consuming these seasonal greens also acted as preventive healthcare: the nutrients in them addressed constipation, digestive issues, even jaundice in infants, long before fibre supplements or packaged tonics entered diets.

Take doddagunisoppu, a common seasonal weed known to ease constipation. Or goddarvesoppu, crowned the ‘king of weeds’, which thrives in manure-rich parts of fields and is considered one of the tastiest edible greens. Kolichitka, the smaller wild cousin of mustard, is often called the ‘original mustard’ for its intense fragrance and is used to season meals. Honnari gedde seeds are traditionally given to new mothers to help induce lactation. Wild amaranth grows thorns to protect itself, but its tender leaves are used to treat kidney stones.

Beyond nutrition, weeds also signal soil conditions.

For farmers, the colour, shape, and texture of leaves are crucial cues to distinguish what is edible and what is not—knowledge passed down across generations. Beyond nutrition, weeds also signal soil conditions. Certain species indicate fertile, manure-rich patches, others reveal the pH of the soil and excess moisture. To remove them indiscriminately is to lose this language of the land.

Also read: Foraging in Bengaluru: A source of sustenance and flavour

Today, much of this knowledge is disappearing. Many farmers believe that cultivation isn’t possible without commercial pesticides, which seem to promise quick returns but come at a massive environmental expense. Many commonly used herbicides contain toxic compounds such as glyphosate, atrazine, and 2,4-D (all of which are classified as probable human carcinogens), which can persist in the soil and disrupt beneficial microbial communities essential for soil fertility. These chemicals don’t just kill weeds, they can also leach into groundwater or enter nearby water bodies through runoff from fields, contaminating drinking water sources and harming aquatic life by interfering with plant growth and hormonal systems. They can persist long enough to enter the harvest that eventually reaches our plates. Herbicides harm farmers too, through chemical inhalation and skin absorption during mixing and spraying. Though often seen as benign tools that make for productive and prosperous farms, herbicides are in fact a specialised class of pesticides, carrying similar toxic compounds that have long-term repercussions on their health.

Cover crops (a class of crops that are planted before the main harvest crop to fix nitrogen and endow the soil with biomass) like mustard, can naturally suppress pests and act as biofumigants. However, these are often replaced with herbicides which strip the fields of biodiversity and make farms increasingly dependent on chemical inputs, weakening the resilience of rainfed systems over time.

Mechanised monocropping meant that weeds were no longer given the same importance.

The arrival of mechanisation—rotavators, seed drills, threshers—reduced labour but demanded uniformity. Intercropped fields were harder to till and harvest mechanically, so farmers began segregating crops into neat, single-species plots. Mechanised monocropping meant that weeds were no longer given the same importance. It also contributed to the loss of the repository of knowledge surrounding local, edible weeds that may have been previously passed down in farmers’ families.

Also read: The grave personal cost of pesticide use

Deweeding without herbicides does not mean letting fields run wild. Traditional deweeding by hand, though more labour-intensive, is deliberate and selective. Farmers remove weeds that compete directly with young crops, while allowing others—especially edible and medicinal plants—to remain.

On GFM’s ragi plot in Tiptur, this approach means observing which weeds emerge close to seedlings and which grow along bunds or manure-rich edges. Some are thinned, some are harvested, and some are left untouched. The goal is not a ‘clean’ field, but a balanced one.

Mulching works by covering the soil with crop residue or organic matter. This process helps shelter soil from harsh sunlight and prevents aggressive weeds from germinating. At the same time, it conserves moisture—critical in rainfed farming (but which dissuades weeds from growing)—and feeds soil organisms as it decomposes. Unlike chemical sprays that act instantly but leave lasting damage, mulching suppresses weeds gently, while improving soil structure and fertility over time.

Deweeding without weedicides is about recognising that weeds are part of farming ecosystems, which beautify fields and diversify our sources of nutrition.

High-density planting shifts the responsibility of weed control onto the crop itself. When plants like ragi are sown closer together, their canopy shades the soil, leaving little room for weeds to establish. This reduces the need for repeated deweeding while improving land use efficiency. Used alongside hand deweeding and mulching, dense planting helps farmers manage weeds proactively by letting the crops lead, rather than reacting after they take over.

Deweeding without weedicides is about recognising that weeds are part of farming ecosystems, which beautify fields and diversify our sources of nutrition. By changing our gaze towards them—the gaze that modern farming and industrial practices have normalised—and co-existing with them, farmers protect soil and preserve ancient repositories of food knowledge.

Adivasi communities in the state have perfected the approach to harvesting sustainably, safely and in a manner that optimises nutrition

Smoke drifts through the morning air. Ganesh Wadaka, 47, stands beneath a mango tree, eyes fixed on the nest of a Yellow Paper Wasp clinging to a high branch. He lifts a small bundle of smouldering ebony leaves. A gentle blow. The tekor, as the wasp is locally known, begins to settle.

“One needs to be careful while collecting tekor. Their sting is very painful. The smoke calms them,” Wadaka explains. “We collect only their larvae, roasting them over fire before they are served.” This wasp species has much to offer the Adivasi Dongria Kondh community to which Wadaka belongs: its wax is traditionally used to treat cracked feet, while controlled stings are believed to help relieve edema, coughs, colds, and stomach pain.

The farm around this mango tree in southern Odisha’s Khajuri village lies along the slopes of the Niyamgiri Hills. It remains a landscape that the Dongria Kondhs, one of India’s Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG), revere and protect as the home of ‘Niyam Raja’, their supreme deity.

Much like the Yellow Paper Wasp, Red Weaver Ants, too, are a beloved ingredient—one that has travelled beyond Adivasi villages. In the Mayurbhanj district, Santals prepare kai chutney (the local name for the ant species) using its larvae (a recipe for the chutney can be found at the end of this article). This savoury, tangy relish received a GI tag in 2024 for its distinct flavour and nutritional value.

{{marquee}}

Red weaver ants build brood-pouch nests by wrapping sal or mango leaves together. The Santals’ consumption of the insect is neither mindless nor clued out of the species’ habits and survival. “We don’t consume the adult ants, we only collect their eggs and the juveniles. We crush them with red chilli, mint and salt to make the chutney, which is usually eaten with pokhal, a traditional fermented rice,” explains Sarita Hansda, who resides in Mayurbhanj’s Gopinathpur village.

Freshly foraged kai is also sold by Santal women in weekly village markets, earning an additional source of income for their households. Santal healers believe that kai helps treat a range of ailments, including jaundice, arthritis, nervous disorders, and memory loss. Healers in the community infuse oil with kai for a month, and then apply it to infants. The medicinal oil is also believed to ease rheumatism, ringworm, and other skin conditions. At other times, kai is used in a nutritious soup that helps cure ailments, dysentery, cold, and fever.

Across Odisha’s rainfed regions, produce obtained from farming is only one aspect of the diet of Adivasi communities, who cultivate millets, paddy, pulses, cereals, oilseeds, and tubers through mixed, diversified practices. They also forage wild roots, tubers, leafy greens, mushrooms, and fruits that sustain households year-round. Among their diverse diet, edible insects are a crucial part, supplying protein and micronutrients that have nourished generations.

“We grew up eating what the forest gave us. Insects were always part of our meals—a heritage of our ancestors,” says Abhiram Jhodia, 51; he belongs to the Paroja Adivasi community in the Siriguda village. “From childhood, we learned to read the seasons through ants, wasps, and caterpillars. This traditional knowledge, passed down through stories, helped our ancestors survive. We take only what we need and leave enough for the insect colony.”

Sujata Giri, a 46-year-old Santal woman from the Tamalbandha village, recalls venturing into the local forest with her mother, on the lookout for wild edibles. “Watching her closely, I learned how to spot the nests of insects that are safe to eat, and the right season during which they can be collected.” Muni Kalundia, another Santal woman from the Saruda village, shares similar memories of familial warmth and household nutrition. For her community, these insects were not just cultural foods, but everyday sustenance during lean months, when grains were scarce.

Among their diverse diet, edible insects are a crucial part, supplying protein and micronutrients that have nourished generations.

The range and diversity of insects consumed by Odisha’s Adivasis include winged termites, silkworm pupae and spotted crickets. Sindhe Wadaka, a 53-year-old community leader from Khajuri, speaks of caterpillars found in bamboo stems, locally known as baunsa poko, which enjoy great value in maternal diets and care. Roasted baunsa poko are given to pregnant women, as they are believed to help improve blood supply and provide nourishment.

Also read: Black Soldier Fly: A hero of insect farming and waste management

Climate change and habitat degradation are impacting the populations of edible insects across Odisha. Erratic rainfall, in particular, has had an adverse effect on palm worms, bamboo caterpillars and winged termites, says Debabrata Panda, Assistant Professor at the Central University of Odisha, Koraput. “Since these species are largely foraged during the monsoon, shifting rainfall patterns are disrupting their availability,” he explains, adding that the growing use of agricultural chemicals is also wiping out insects once commonly found around farms.

“Sindhi kida was once abundantly found around the roots of palm shrubs. Now, locating them is tough,” says Dibakar Sabar, 58, from the Goiguda village in Rayagada. These sindhi kida–also called Sago worms–are among the most sought-after edible insects foraged by the Paroja, Kondh, Bonda (PVTG), Saora and Santal communities. They can be eaten raw, roasted or fried, and are known for their chewy, juicy texture and flavour, often compared to boiled chicken.

The range and diversity of insects consumed by Odisha’s Adivasis include winged termites, silkworm pupae and spotted crickets.

Similarly, snails–once abundantly found in paddy fields, ponds and rivers–have declined sharply. For Adivasi communities, snails are a cherished delicacy, often cooked into flavourful curries or fried dishes like the Santal Gongha Uttu. Known as gongha in the Santali language, snails are widely believed to offer multiple health benefits, improving eyesight, easing asthma and joint pain, supporting kidney health, boosting immunity and strength, and preventing anemia.

“In our community, we have always fed snails to pregnant women and young children,” says Saibeni Murmu, 60, a Santal woman from Bhagabandi village. “Our elders taught us that snails help new mothers regain energy, and children grow healthier. Ancestors believed that the strength of the forest lives within these creatures, and that eating them builds immunity, and keeps sickness away. But now, we are seeing less and less of them.”

Also read: Bugging out: Why declining insect populations in India spell doom for agriculture

The traditional knowledge on entomophagy–the practice of eating insects–is slowly slipping away. “Entomophagy is more common among the older generation, especially those above 50,” says Abhishek Pradhan, agricultural expert with the Watershed Support Services and Activities Network in Bhubaneswar. Over the past few years, Pradhan has worked closely with Adivasi communities, facilitating community-led documentation of forgotten and wild food cultures in more than 40 villages across the Malkangiri and Nuapada districts.

He observes a clear shift in the younger generation: those between 18 and 30 increasingly gravitate toward cereal-based diets influenced by market availability as well as changing lifestyles and aspirations. At the same time, a lingering stigma surrounds many wild foods, often labelled as ‘Adivasi food’—a term that distances young people from the very culinary traditions that sustained their ancestors for generations. “This disconnect is worrying,” Pradhan explains. “As these food practices fade, the deep ecological knowledge and local traditions tied to them also risks being lost.”