The Padma Shri awardee is on a mission to restore biodiversity in Indian farming

Editor's note: Every farmer who tills the land is an inextricable part of the Indian agriculture story. Some challenge convention, others uplift their less privileged peers, others still courageously pave the way for a more organic, sustainable future. All of them feed the country. In this series, the Good Food Movement highlights the lives and careers of pioneers in Indian agriculture—cultivators, seed preservers, collective organisers and entrepreneurs.

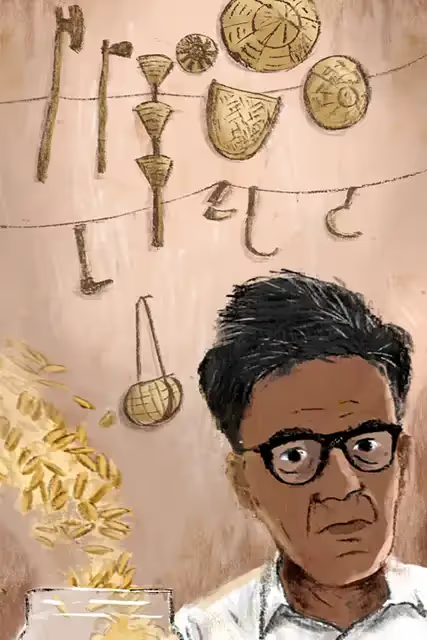

A chameleon rests on the back of a couch; children wander in and out of rooms; and a dog, upon whom tiger stripes have been painted by the children, prances around playfully. At Babulal Dahiya’s home in Madhya Pradesh’s Pithaurabad, which doubles up as a museum of forgotten agricultural tools and traditional cooking utensils, the pace is anything but slow. A crow lands on the porch from time to time, while a few sparrows—a rare sight in India’s cities— chirp away. Outside, cows and their calves peek through the entrance.

An otherwise narrow, quiet lane in the Unchahara tehsil of Satna district turns lively on the early April afternoon when we visit Dahiya. The 83-year-old farmer, poet and retired postmaster is the beating heart of this neighbourhood. He is also a recipient of the Padma Shri (2019), India’s fourth-highest civilian award, for his contributions to agriculture—particularly to organic farming and the conservation of indigenous crop varieties.

When Dahiya speaks, he blends personal memory with documented and undocumented fact, offering a perspective shaped by decades of working in fields, writing, and collecting grassroots knowledge. His home and life reflect a vision where culture, ecology, and rural identity continue to inform each other. As a writer who nurtured a long association with the Adivasi Lok Kala Academy—an MP state initiative to promote tribal culture—Dahiya has published detailed studies on the Kol and Khairwar communities backed by extensive research.

The octogenarian is frail; he climbs up a flight of stairs to show us the three rooms he has turned into a museum, which leaves him momentarily breathless. He pauses to rest before slowly resuming, carefully walking this writer through the many objects and memories he has preserved over the years.

“I inherited farming,” he says, as we sit down to talk, “We have been farmers for generations. My father practised agriculture, as did my grandfather before him.” As a boy of eight or nine, he was sent to another town to study, returning home only during fasli chutti [harvest holidays]. It was the early years of India’s independence. “Back then, we had harvest holidays from Dussehra to Diwali—nearly 28 days long. I would do everything that children could do to help,” he recalls, "Hum ek mah chidiyon ki takai aur dhan ki gahai karte the aur damri chalate the. [For a month, I used to guard the crops from birds, pound the paddy, and operate the manual threshing device]."

Observing these fields became a form of education for a young Dahiya. He revisits memories of how sorghum was often intercropped with lentils and other staples like green gram, black gram, pigeon pea, sesame, and kenaf. Those early experiences, he believes, taught him more about agriculture than any textbook could—simple yet rarely documented lessons such as which crop attracts which species of bird or animal. Parrots, for instance, were known to go straight for the sorghum.

He says in jest, “Kauwe ka rang kaala hota hai, ye humko padhkar nahi pata chala. Woh humko kauwe ko dekhkar pata chala. [I didn’t learn that a crow’s plumage is black by reading it in a book. I learned it by seeing the crow].”

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

The decline of indigenous crops

The passage of time made Dahiya witness to the drastic changes and losses the surrounding ecosystem was undergoing. But the loss that felt most personal was of indigenous rice varieties—which faced the highest risk. His family farmed on two plots: one in Pithaurabad, and another in Birpur, three kilometres away. Through his chronicling of folklore, he saw how traditional mixed cropping was being replaced by monocultures. “The farms and fields weren’t as colourful as they used to be,” says Dahiya, recalling the decline of diverse dhan (rice) varieties.

This shift came about a decade after the Green Revolution. It was the introduction of IR-8, a high-yield rice strain developed by the International Rice Research Institute, in 1967—first introduced in Andhra Pradesh, and later across the country—that marked a turning point in India’s farming history.

Dahiya acknowledges the necessity of the Green Revolution in its time. “The country struggled with famine and diseases such as smallpox, malaria, and plague. We needed a stronger food system. I adopted its principles, too. But, as the saying goes, ‘Science is a blessing, but beyond a point, it can become a curse,’” he adds.

No one anticipated the long-term effects of what was deemed a ‘revolution’. “Puri ki puri dhane khatam ho gayee [The entire stock of traditional rice varieties disappeared]. It was a blessing until the 1990s.” By the mid-to-late 1990s, he realised the urgent need to preserve native rice seeds. This marked the beginning of the work he is known and recognised for: beginning with 15 varieties, by the late 2000s, he had collected 110, and now his bank boasts of around 200.

While walking this writer past rows of seed jars, Dahiya pauses at certain varieties, opens a jar and spreads the grains in his creased palm. He explains their traits patiently, peeling back the husk to show the grain inside. He picks Galari, named for its husk that resembles a myna’s eye—rounded, bordered, and striking. Then he reaches out for Kalavati, a black rice with long spikes and a rough husk; inside is a dark brown grain with a lighter tip, akin to a glinting bead. “These are nature’s marvels,” he notes, referring to their diverse qualities and their ability to thrive in different conditions.

In a handmade booklet, he writes: “Like soybean, it’s hard to trace when or where a grain originated... But we can confidently say paddy is the oldest grain in our country... Today, there are many hybrid varieties developed through research. But in ancient times, it wasn’t scientists who discovered them, but farming ancestors who brought them from the forests into fields. The wild ancestors are gone; what remains, survives only with farmers. That’s why saving traditional varieties matters... If even one disappears, so do its traits preserved for thousands of years in tune with this land’s ecology.”

Suresh Dahiya, a journalist and the veteran farmer’s son, talks about a variety called Saathi or Sathiya, known for its short growth cycle. It typically ripens within 60 days of planting—the characteristic that gave it the name. “This makes it ideal for regions with short growing seasons or water scarcity, such as Bundelkhand and parts of Uttar Pradesh. It’s also useful for farmers aiming for multiple harvests a year,” he explains.

“The seed bank is regularly visited by farmers across the country,” Suresh says. “Most come looking for specific seeds—rice or wheat varieties. Some, like the rice variety, Ram Bhog, are both popular and hard to find now. There are about 15 such varieties.” Farmers from faraway villages and towns also write in to request seeds, which are gladly dispatched to them by Dahiya and Suresh, with the courier cost covered by the recipient.

Conservation costs run deep

“The work he was doing was important, and he had the support of our whole family,” says Suresh. Over the last three years, the 59-year-old has taken over his father’s seed-saving effort. While two acres of their farmland in Pithaurabad are reserved for seed preservation, the remaining five are leased out on batai basis (sharecropping). “We grow 25 wheat varieties,” Suresh says, pointing to the ripening stalks.

It takes an investment of Rs 5,000–7,000 per season to grow wheat, he notes, but preserving over 200 rice varieties has become a far more expensive project—around Rs 60,000 per season in recent years. This cost is not just due to the larger number of paddy varieties, but also the technical demands of rice cultivation, which calls for more water, labour, and care—especially since each traditional variety has its own distinct sowing and harvesting cycle.

Financial aid for Dahiya’s conservation efforts has been minimal. Around 2010, the Madhya Pradesh Rajya Jaiv Vividhta Board/Madhya Pradesh State Biodiversity Board helped set up the seed bank, but beyond that, state support has been scarce. For over two decades, Dahiya has sustained his work through an NGO, the Srajan Samajik Sanskritik Evam Sahityik Manch.

“We receive some funds, but they barely cover the basics. We often dip into our own pockets,” Suresh admits. Sadly, Dahiya’s Padma Shri honour has not moved the needle on this front. What’s more disheartening, he says, is that despite growing research backing traditional and organic farming, the larger agricultural ecosystem still prioritises high yield over awareness and sustainability.

Also read: How an Alappuzha coir exporter nurtured a one-acre forest

The ‘yield’ dilemma

A persistent obsession with higher yields has—and continues to—do more harm than people realise, Dahiya says. He recalls memories of a 2012 exhibition in Delhi where he showcased 110 native rice varieties: a group of scientists, including plant geneticist and agronomist M.S. Swaminathan, visited his stall. One of them asked, “Which variety delivers the highest yield?” Dahiya explained that traditional rice varieties often yield about 80–85% in the first year, drop to 25–30% in the second, and give nearly nothing by the third if seeds are reused. “That’s how it has worked for thousands of years,” he told the group, “They’ve survived (all these years) because they’re strong in other ways—by adapting to the soil, warding off pests and surviving the seasons. If you chase only yield, you’ll kill off these crops in three years.” Some of the scientists were embarrassed by their line of inquiry, while Swaminathan smiled at his comment, Dahiya says.

Unlike modern high-yielding varieties (HYVs) introduced in India during the Green Revolution, which often demand new seed stock each season in order to perform well, traditional landraces (old, local crop types that farmers have saved for eons) are more resilient to local conditions, but may see some natural decline if not carefully selected and saved. The exchange, Dahiya felt, underlined a deeper tension: between sustainable seed saving practices and the push for uniform, industrial-scale production that has steadily eroded biodiversity. The problem has grown multifold since Dahiya’s interaction with the scientists.

The resultant fallout

“Look at what this race for higher yields has led to. Our water is gone, the trees and plants have dried up, even orchards have withered. We’re living under a curse. The consequences are so far-reaching that our villages have been cut off from the larger economy. Crop prices have crashed,” Dahiya rebukes. It’s not just farmers who have suffered; the livelihoods of agricultural labourers, too, have declined. A plunge in income levels has made them flee to cities, he remarks.

“Agriculture today belongs to the seths [capitalists],” he says. This is in stark contrast to how things were in the past, when a sense of collectivism brought together a village; where grain was shared with the oil presser, cobbler, blacksmith, carpenter—all those who supported the farmer in return. What remained with the farmer was sold or bartered in the town.

Now, Dahiya rues, every step a farmer takes is controlled by a different seth in the system. Seed agents, fuel suppliers, fertiliser sellers, pesticide dealers, harvest contractors, and middlemen at the market. “Like the cow whose milk is sold, and whose calf gets only a measly 20%, the farmer is left with next to nothing.”

The problem, he says, goes beyond those who work in the fields. With the industrialisation of agriculture, the many professions that once directly supported farming—such as carpenters, blacksmiths, and weavers—have been disappearing, as have the tools they fashioned and used. Carpenters don’t make mogris (pestles) or dedhas (traditional ploughs) anymore. “This is why I began putting together and preserving over 300 farming objects and tools in my museum,” he says.

The process of collecting these objects has been long and slow. When people heard about Dahiya’s vision, some came forward with the tools and items now displayed in the museum. Other exhibits had to be specially made. Dahiya had to find workers who possessed the skills to create replicas while knowledge about the tools was still available. “Only about 20 percent of what you see in the museum is still in use,” he says. “Most of the stone tools, especially, have gone out of use entirely.” The one that can still be found in homes is the pichkariya—a small, rounded stone used to lightly crush cooked dal. Dahiya also draws our attention to wooden implements like the khat-khata (tied around the neck of cattle), dhera (used to tie cattle ropes) and ghota (a cylindrical tool used to administer medicine to animals).

In one corner, an old kolhu stands upside down. Dahiya shows it to us with pride and explains how the traditional oil press worked—where the presser stood, where the bull was tied, where the oil dripped from, and how the whole system came together. He has been trying to get a palki made for a few years now. “But the workers who could make one are either too old now, or have passed away. Their children never learned the craft—not even enough to make a sample.”

The museum sees at least one visitor every day. Sometimes, a few school buses show up and suddenly, there are hundreds of children walking around, surprised by things they’ve never seen before. “Some have suggested that I should move the museum out of my house,” he says, “but that would require more space and more funds.”

Where literature and agricultural wisdom meet

Literature intrigued Dahiya as he grew up. Writing in the Bagheli dialect across fiction and non-fiction, he has documented traditional ballads and idioms tied to tribal festivals and farming. One saying he often quotes is about kargi, an endangered and traditional variety of rice. “Dhaan boye kargi, suar khaaye na samdhi.” Its black husk is covered in spines, making it unpalatable to wild boars (an ongoing problem in forested farming areas)—and unsuitable for serving to in-laws or guests, who are traditionally offered fine white rice varieties like Vishnu Bhog, as a mark of respect.

More age-old proverbs followed in our conversation. “Teen paak do paani, pak aayin kutuk rani,” he recites, referring to how little millet (kutki) ripens with just two spells of rain in three fortnights. “Sama jetha ann kahaye, sab anaaj se aage aaye,” describes sama (also little millet) as the eldest grain, ready to harvest in just 45 days. “Sagman, sarahi, dahiman, rana…assi baras na hoye purana,” compares kodo millet (rana, the ‘king of grains’) to sturdy timbers like sagwaan (teak), sarahi (Indian Kino) and dahiman (Indian laurel), all said to last 80 years without ageing.

Also watch: How women in this tiny Naga village are safeguarding local seeds

Building for the future

During a seed-saving drive in 2017, Dahiya travelled across 40 districts in Madhya Pradesh. “He would stay overnight with farmers to learn about their lives and problems,” says Suresh. This journey significantly expanded their seed bank. One friend, Ram Lotan Kushwaha, contributed over 32 varieties of lauki (bottle gourd), more than two dozen types of brinjal, and at least 15 tomato varieties from his farm.

Yet, a return to traditional practices remains a steep, uphill task. “We work on a small scale because we’re driven. There’s no policy support, no larger framework to connect these efforts. But it is urgent,” says Suresh. Sourcing and hunting for traditional grains is harder than ever, he adds. “Fifteen or twenty years ago, you could still get your hands on a few. Now, it’s nearly impossible.”

Dahiya finds this development extremely concerning. “India has a growing reliance on merely three grains—rice, wheat, and maize, of which high-yield varieties are preferred.” Not only has the disappearance of coarse grains (mote anaaj) narrowed the scope of people’s diets, but it has also contributed to a rise in lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and obesity. “Previously, people had ‘family doctors’. Now, in order to reclaim their health, they need ‘family farmers’—trusted cultivators who can grow organic, local grains for them,” he says with a chuckle. As Suresh takes forward the work he began, Dahiya remains hopeful—not all will be lost.

Illustration by Tarique Aziz

Produced by Nevin Thomas and Neerja Deodhar

Explore other topics

References

.avif)

.avif)