The rise of inorganic varieties threatens our rich tradition of seed saving, increasing input costs and the strain on farmers

Seeds mark the beginning of all food security, and by extension, the foundation of agriculture and the beginning of all life. In India, where agriculture is deeply ingrained in culture, seeds have never been regarded merely as farming inputs. They have long been symbols of abundance, passed down and exchanged across generations.

But in today’s industrial food system, choosing a seed is no longer a simple act. It is a political, economic, and ecological decision. With India having the sixth-largest domestic seed market in the world—worth over ₹10,000 crore—our seed choices are increasingly shaped by market forces, agribusiness corporations, and policies, rather than by farmers and communities.

Seeds, pre- and post-Green Revolution

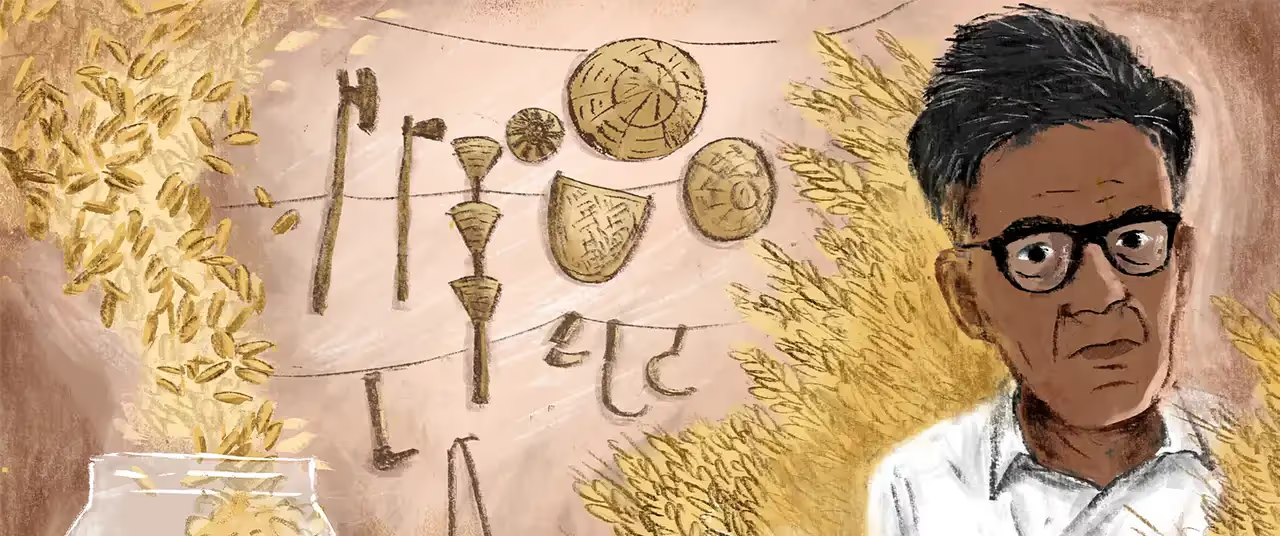

As Krishna Prasad, the founder of Sahaja Seeds, says, “Traditionally, in India, seeds were part of the commons—[goods] freely exchanged through community networks and rituals. For instance, during marriages or housewarmings, navadhanya (wheat, rice, toor dal, chickpeas, moong beans, white beans, black sesame, Indian black lentils, and horse gram) were given importance.”

Indigenous seed systems relied on open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) that evolved through natural selection and local adaptation. These seeds were adapted to microclimates, soil types, and farming practices. Importantly, they could be saved and reused, strengthening local control and autonomy.

Women were often the custodians of seeds, passing down knowledge through oral tradition and lived experience. In many parts of India, the role of women in seed preservation is still acknowledged through festivals and seasonal rituals.

Indigenous seed systems relied on open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) that evolved through natural selection and local adaptation.

This transition to the modern dilemma of seed differentiation occurred following the Green Revolution, which took place in the 1960s. The Green Revolution was introduced in response to the risk of a series of famines between 1947 and 1960, as well as to increase food production, alleviate poverty, and feed millions. With support from international institutions, the government introduced high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of rice and wheat.

Before the 1960s, Indian farmers practised multicropping cultivation, later shifting to two crops per year during the time of the Green Revolution, a period marked by the “commercialisation/commodification” of farming. Moreover, farmers who grew traditional crops for their own consumption shifted to cash crops; cropping patterns shifted from diverse, input-sharing mixed farming to monocultures driven by external hybrid seeds. This has altered not just what farmers grow, but why they grow it—profit has replaced food and ecological security as the core purpose. In pursuit of high returns, many farmers now grow cash crops that involve higher risks, higher production costs, or long-term vulnerabilities. The system was arranged in such a way that there was increased use of chemical fertilisers, pesticides, insecticides, mechanisation, and institutional reforms, while traditional agriculture and knowledge were sidelined. As Krishna Prasad says, “There was a constant push from the government in the form of subsidies, loans, and targets upon officials to shift to conventional farming.” Thus, big multi-corporations started controlling seeds.

Also read: Babulal Dahiya makes every grain of rice count

Understanding seed types

- Organic or open-pollinated seeds: Organic seeds are those that are grown without synthetic chemicals and are derived from open-pollinated varieties, which means that pollination occurs through the actions of insects, birds, wind, humans, or other natural mechanisms. These can be saved and replanted and often improve performance when adapted to local conditions, climate, and soil.

For example, in northern Karnataka, farmers save seeds from plants that have consistently survived the region’s hot, dry weather. Over time, these seeds adapt and require less water, becoming stronger in challenging conditions. Along Karnataka’s coast, farmers select seeds from rice plants that can withstand salty sea breezes and heavy rains, ensuring future crops resist flooding and salt damage. In both cases, plants are allowed to cross-pollinate naturally—through wind or insects—so that beneficial traits spread within each ecosystem. Moreover, when parent plants endure drought or salinity stress, they transmit biological signals to their seeds, enabling the next generation to grow better under similar tough conditions.

Prasad refers to them as “seeds of resistance” that protect both ecological balance and farmer autonomy. He names Papamma in Mulgabal and Aftab MB in Udupi, Karnataka, as examples of seed savers who have conserved over 500 native varieties like navane (foxtail millet), karibhatta ragi, and hurali (horse gram).

These seeds are often dismissed as “primitive cultivars” or “landraces.” But in reality, they form the genetic bedrock of agricultural resilience and food culture local to India.

- Hybrid seeds: Hybrid seeds are created by crossing two genetically distinct parental lines from the same species to produce first-generation (F1) hybrids. These seeds exhibit hybrid vigour, often resulting in uniform growth, resistance to disease, and higher yields.

The history of the hybrid seed goes as far back as early 20th-century plant breeding trials. In 1908, American geneticist George Harrison Shull showed that the mating of two pure maize lines resulted in the birth of a vigorous offspring—a process referred to as heterosis or hybrid vigour. This provided the basis for hybrid seed technology. Commercial hybrid maize became available in the US during the 1930s, transforming corn farming by markedly increasing yields and resistance to disease.

In India, the use of hybrid seeds accelerated during the Green Revolution, particularly for cereals such as maize, sorghum, and pearl millet. Hybrid varieties were extensively advertised, and officials used to promote their yield potential based on government subsidies and irrigation facilities. However, this vigour does not carry forward as hybrid seeds do not breed true. If a farmer saves and replants hybrid seeds, the second-generation crop shows genetic segregation, leading to unpredictable and often inferior yields.

Hybrid seeds are created by crossing two genetically distinct inbred parent lines to produce the first-generation (F1) hybrids. These F1 plants display hybrid vigour (heterosis) and uniformity, resulting from the combination of complementary alleles. However, when F1 plants self-pollinate or interbreed, their offspring—the F2 generation—inherit a random assortment of chromosomes. This leads to genetic segregation, where different combinations of parental genes are distributed among individual plants, causing significant variation in traits such as size, yield, taste, and overall uniformity. Due to this segregation, seeds saved from hybrid crops do not “breed true,” meaning the next generation fails to consistently reproduce the desirable characteristics of the original hybrid. As a result, farmers must purchase new hybrid seeds each season to maintain the same quality and performance. Moreover, hybrid crops are typically input-intensive, requiring chemical fertilisers and pesticides for optimum performance. This increases production costs and ecological risk. Hybrid seed markets in India have become tools for corporate monopolisation, where private firms determine access, pricing, and availability.

- Genetically modified (GMO) seeds: Genetically modified (GMO) seeds involve the insertion of genes from unrelated organisms—like bacteria or viruses—into the DNA of a plant to produce desired traits such as pest resistance or herbicide tolerance. They first came to India in the 1990s, albeit grown illegally until 2002, which is when the government regularised them, starting with Bt cotton. Essentially, they are not bred in gardens but in biotechnology labs, and are termed as “genetically modified.” This is an advanced system where GMO seeds produce their own insecticide, eliminating the need for external application. Aftab MB says that GMO seeds are “completely against the arrangement of nature.”

The most well-known GMO in India is Bt cotton, which contains a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis—a soil-dwelling bacterium—to kill bollworm pests. While initially successful, the technology has shown diminishing returns, with new pests emerging and farmers returning to pesticide use.

GMO seeds are often patented, meaning that farmers cannot save or reuse them legally. Companies retain ownership of the seed genetic code, even after sales. Civil society groups, such as The Non-GMO Project, Gene Campaign, and the Heinrich Böll Foundation, have raised concerns about the potential risks of GMOs to biodiversity, food safety, and farmer sovereignty.

{{quiz}}

Seeds, power, and the political economy

India’s seed economy today is highly commercialised. The seed industry is estimated to have a turnover of over ₹10,000 crore and continues to grow rapidly every year. While public institutions, such as the National Seeds Corporation (NSC), still play a role, private companies have started to dominate the hybrid and GMO seed markets from the late ‘80s.

Confusion between hybrid and GMO seeds is common, and literacy around seed types is low—especially in rain-fed and tribal regions.

The proposed Seed Bill 2020 has sparked debate, with critics arguing that it prioritises corporate breeders’ interests over farmers' rights. Licensing requirements, mandatory registration, and the potential for criminalisation of seed saving are key concerns. Additionally, many farmers are unaware of the origin or classification of the seeds they use. Confusion between hybrid and GMO seeds is common, and literacy around seed types is low—especially in rain-fed and tribal regions.

This commodification also has gender-based implications: as women lose control over seed selection and storage, their stake in agriculture becomes invisible, despite their central role in biodiversity conservation. With the rise of patented seeds sold by multinational corporations, women farmers have become increasingly dependent on purchasing seeds each sowing season, rather than saving and sharing them. This shift undermines their traditional roles and authority in agriculture, diminishing their visibility and influence, even though they continue to carry out much of the farm labour.

Also read: One Odisha woman’s mission to preserve taste, tradition through seeds

Grassroots resistance and action

Despite institutional barriers, farmers across India are reviving seed sovereignty through community seed banks, farmer-led breeding, and heritage seed festivals. The Aikanthika Heritage Seed Mela has been held across multiple locations since 2024, and the Desi Seed Festival, organised by Sahaja and other NGOs since 2006, is held annually in Davanagere and Mysuru, Karnataka, respectively. Such initiatives, where hundreds of farmers exchange native varieties of ragi, paddy, legumes, and vegetables, are beneficial to the seed ecosystem. These gatherings are both cultural and political, challenging monoculture and celebrating biodiversity.

Sahaja Seeds, India’s only farmer-owned organic seed company, has built an extensive network of seed producers across India. Likewise, Sahaja Samrudha and Bharat Beej Swaraj Manch are among the handful of national-level players whose models emphasise ethical seed production, capacity building, and preserving neglected varieties.

Women farmers and the youth are also leading the way in seed saving. As Prasad says, “Seed saving reduces dependence on expensive commercial seeds, lowers input costs, and preserves crop varieties adapted to local climates and stresses. This financial and ecological independence empowers women farmers.”

Why seeds matter now, more than ever

As climate risks intensify—unpredictable monsoons, droughts, floods, and pest outbreaks—the need for diverse, locally-adapted seeds has never been greater. Studies have shown that indigenous seeds are more resilient under climate stress than hybrids or GMOs. For instance, native varieties of bajra and jola in Karnataka withstand dry spells far better than imported hybrids.

Traditional seeds have undergone in-situ evolution, meaning they continuously adapt to local climate patterns, soil conditions, and pest pressures. They also have a broader genetic base with multiple alleles that provide resistance to stress traits, unlike hybrid seeds, which are genetically uniform. This genetic diversity enables them to withstand various environmental stresses through natural selection. Traditional varieties also contain stress-responsive genes (such as the glutathione transferase family), which are activated under multiple stress conditions, providing cross-protection against drought, heat, and disease. Moreover, grains such as millets and pulses are rich in micronutrients, making them essential for achieving nutritional security.

As climate risks intensify—unpredictable monsoons, droughts, floods, and pest outbreaks—the need for diverse, locally-adapted seeds has never been greater. Studies have shown that indigenous seeds are more resilient under climate stress than hybrids or GMOs.

Organic seed systems also contribute to soil health, carbon sequestration, and reduced dependency on fossil fuel based inputs. Their success depends on practices which will increase soil organic matter, such as long-term use of manure, compost, crop rotations, multicropping, cover crops and crop residues, which increase porosity, and water holding capacity. As organic matter accumulates, carbon is sequestered in stable soil fractions—such as humic substances and particulate organic carbon—locking atmospheric carbon dioxide into the soil and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Because organic systems avoid synthetic nitrogen fertilisers and petrochemical pesticides (whose production and application consume large amounts of fossil fuels), they substantially reduce energy use and fossil fuel dependency compared to conventional farming.

From the consumer’s perspective, buying organic varieties helps build market demand for traditional seeds. Each conscious purchase reinforces the entire ecosystem—from the farmer to the soil to the seed.

Seeds are not just agricultural tools—they are deeply interconnected to justice, memory, and survival. In a world of rising climate risks and market dependency, our seed choices reflect the kind of future we are sowing.

Also read: The tribal seed guardians of Dindori

Explore other topics

References