What a nature-conscious solution to a primate problem tells us about Mandeep Verma’s farming philosophy

When Mandeep Verma, a former marketing professional, left behind his lucrative career at Wipro in Delhi and moved to Himachal Pradesh in 2015 to start farming, he expected challenges to come his way—challenges that are typical of Indian agriculture. What he didn’t expect was that one of the biggest hindrances he would face would be monkeys (rhesus macaques) and langurs. “The monkey menace,” he calls it. No plant being grown in the area is safe—from maize to potato and tomato, monkeys eat all of it and harm every plant.

Verma’s journey started with a simple wish—to move back to his hometown of Shili, a small village in the Solan district so that he could be close to his parents, and so his kids could grow up in humble surroundings with clean air, fresh water and a thriving environment. He returned to the roughly 41 bighas (1 bigha is about 0.619 acres, making the land 8.199 acres) of barren land he owned in his village. Even as he started cultivating and working on the land, with an initial investment of ₹4 lakh, he was greeted by monkeys destroying his saplings. “It’s a widespread problem in Himachal,” he says. “Some people rely on solar fencing. It gives a mild shock to the animals, but they don’t die. Other people even poison the monkeys, but that’s not good. We shouldn’t be killing other creatures for our benefit,” he adds.

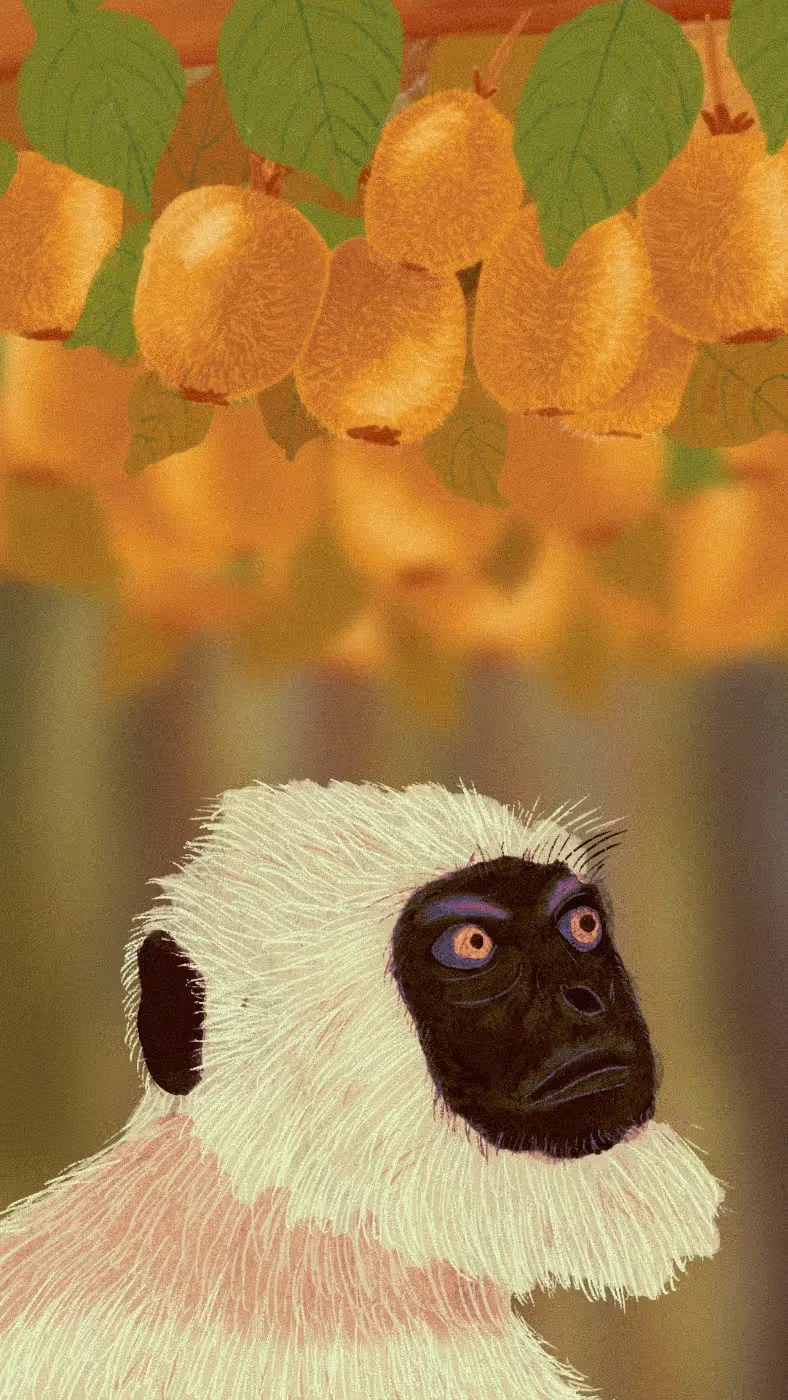

He started researching, looking for alternative crops that would be safe from the monkeys. His search led him to Dr. Vishal Rana at the Department of Fruit Science at the Dr. Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture & Forestry in Himachal Pradesh, who encouraged him to grow kiwis. “When it [the kiwi fruit] is harvested, it is hard and very, very bitter,” says Dr. Rana. It also has a spiky, hairy texture outside, which deters the monkeys from repeatedly plucking it. Besides tackling the monkey problem, kiwis also make for a practical choice, since they don’t require any specific packaging and transporting them doesn't require any special provisions. Dr. Rana explains that once ready, they remain ripe for about 10 days, giving farmers plenty of time to market them, within India or abroad. “In terms of water, temperature and soil, kiwis were a good fit for the farm,” says Verma, who grows the Allison and Hayward varieties on his farm.

{{marquee}}

In 2015, Verma started with 150 kiwi plants, observing, for a year, how they respond to the environment and then planting more over time. Over the last decade, he kept adding plants; today, his farm has 1,000 of them, all at different stages of development. Since kiwis are seasonal, as a way of diversifying his business, he also started growing apples, because they are quick in production, giving fruit within a year of being planted. He did this in a high-density farming model; the saplings are placed close to each other on the farm, as a way to increase yield without requiring more land. Besides entering the ecotourism space to grow his earnings further, he’s also got a nursery that adds to the revenue.

However, making peace with monkeys is only one aspect of Verma’s larger mission with the farm, named Swaastik Farms (meaning “wellbeing”). The tagline of his venture is ‘growing responsibly,’ which emphasises the central tenet of his mission.

Also read: Why neem oil is the OG pest buster

Spreading the word

This kiwi model, which so effectively prevents monkeys from destroying farm plants, has, over time, been adopted by several farmers in the area. While other states of India also grow kiwis, Himachal quickly became a forerunner. Some of the farmers have also formed a collective, planting fruit trees such as pomegranates, apricots, and plums within the forest. Their reasoning is that if the monkeys find food in the forest itself, they’ll be less likely to stray onto the farms. In this manner, kiwis are helping farmers settle a longstanding human-animal conflict in the region.

However, making peace with monkeys is only one aspect of Verma’s larger mission with the farm, named Swaastik Farms (meaning “wellbeing”). The tagline of his venture is ‘growing responsibly,’ which emphasises the central tenet of his mission. The farm has 100% organic cultivation and focuses on natural farming, so much so that 95% of what goes into the farm comes from the farm itself. “Because of the farm, my children are eating healthy. So I thought that the food that goes into the markets should also be healthy. The elderly, children, pregnant women—everyone should be able to consume it,” he says.

Also read: The 'plant' doctor will see you now

In this vein, the plants on the farm are grown without any chemicals. Not using insecticides, for instance, means that no insects are being killed. The farmers aren’t forced to use the chemicals, which they would inevitably inhale, and that would then lead to their health deteriorating. This also means that Verma is allowing nature to work its magic. Just one such instance is the ladybugs roaming around on the farm. They automatically check the mite population, keeping the plants safe. “It’s a responsible process. We’re not polluting the soil, water or air with those chemicals,” he says.

{{quiz}}

Instead of using fertilisers or other chemicals, Verma uses naturally-made concoctions to support the plants on his farm. One is called jiva amrit, which is poured onto the soil. To make a 200-litre container of the mix, one needs 10 kilograms of cow dung, 6-8 litres of cow urine, besan (gram flour) for protein, 2 kilograms of jaggery and 200 grams of soil from under or near a tree. “The soil is not dead matter. It has millions of microorganisms. And the microbial activity in the soil is higher around healthy plants. So we take soil for the jiva amrit from there,” he says. This mix is left to ferment for 4-6 days when the microbial count multiplies manifold. They then use spray pumps to shower the farm with the healthy mix. The high microbial count naturally controls diseases and provides nutrition to the plants. “It makes the soil soft since there’s more aeration and less water logging. So there’s no need for chemical fertilisers,” he explains.

These natural methods lead to healthier fruits with longer shelf lives, and many young people are inspired by Verma’s model and seek to emulate it on their land, too. Even as he helps the farmers around him, Verma envisions a revolution where people return to their roots and take to farming again, now that technology has simplified and democratised access to knowledge.

Also read: Peeling profits: Punjab’s kinnow farmers in crisis

Explore other topics

References

Why did experts suggest Verma grow kiwis to deter monkeys?

%20copy.avif)

%20copy.avif)

%20copy.avif)

%20copy.avif)

.avif)