Even if the rains fail, ragi does not let people go hungry, making it a crop that farmers and consumers trust.

Editor's note: Even before its current status as a nutrient-rich superfood, ragi has been a crucial chapter in the history of Indian agriculture. Finger millet, as it is commonly known, has been a true friend of the farmer and consumer thanks to its climate resilience and ability to miraculously grow in unfavourable conditions. As we look towards an uncertain, possibly food-insecure future, the importance of ragi as a reliable crop cannot be understated. In this series, the Good Food Movement explains why the millet deserves space on our farms and dinner plates. Alongside an ongoing video documentation of what it takes to grow ragi, this series will delve into the related concerns of intercropping, cover crops and how ragi fares compared to other grains.

There is a Naga adage that speaks of how “even a single stalk of millet can revive a dying man.” This points not only to the nourishment that millets can provide, but also resilience, a quality that is becoming ever more important in a world of changing climates and fragile food systems. As the planet warms and water becomes scarcer, farmers and researchers are turning their attention back to these ancient grains.

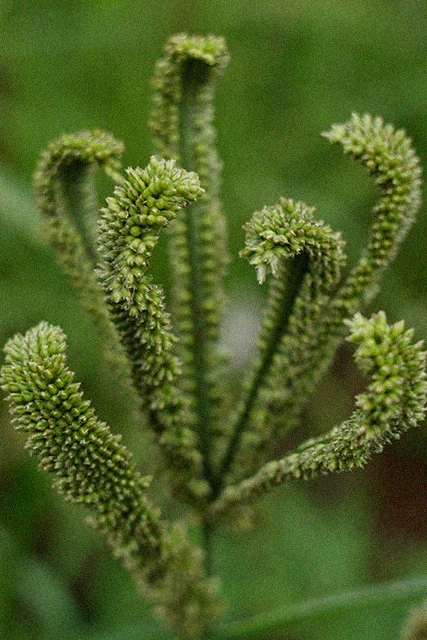

One of them is ragi—also called finger millet, mandua (Hindi), nachni (Marathi), moothari (Malayalam), and kezhvaragu (Tamil) among others. The reddish-brown grain originated in East Africa, and journeyed across the world to wherever people needed a reliable, climate-resilient food source. Its scientific name Eleusine coracana itself tells the story of its travels: Eleusine is the name of the Greek goddess of cereals, and coracana is a distortion of the Sri Lankan ragi porridge korakan. Its common name, finger millet, instead describes the grain’s hand-like panicle. Around 1800 BCE, it found its way to the Indian subcontinent. Over centuries, it became a reliable crop and an integral part of India’s foodscape. Its ability to take many forms, from rotis and biscuits, to malted beverages, has kept it alive in kitchens across the peninsula, especially in the south.

Growing conditions

Ragi’s resilience makes it a crop for the future. Though it exhibits a preference for loamy and slightly acidic soils, it grows even in shallow, infertile, saline or alkaline soils. Similarly, if timed alongside the Kharif season, it can be grown as a rain-fed crop even amid erratic rainfall—conditions under which other staples struggle. Some farmers call it a ‘famine crop’ because once harvested, its seeds can be stored for up to ten years without damage from pests.

Even if the rains fail, ragi does not let people go hungry. It is a crop people trust.

In a changing climate, ragi offers smallholder farmers a lifeline. It requires fewer inputs, reduces the risk of the crop failing, and ensures food security. Women farmers are often at the forefront of millet cultivation, linking ragi to empowerment. In several parts of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, women’s collectives have revived ragi farming not only for household consumption but also as a source of income, tapping into growing urban demand. Even if the rains fail, ragi does not let people go hungry. It is a crop people trust.

Also read: ‘Summer ragi’: How Kolhapur farmers’ millet experiment became a success story

Where it grows

In 2020-21, India produced almost 2,000 tonnes of ragi. Karnataka accounted for 68% of that output, with states like Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Maharashtra accounting for most of the remaining produce. The crop’s presence from the Deccan Plateau to over 2,400 metres above sea level in the Himalayas serves as proof of its adaptability.

In Karnataka, ragi has become deeply embedded in culinary traditions: the earthy, hand-rolled ragi mudde eaten with gravies remains iconic. In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, it takes the form of dosas, porridges, or even malted beverages. Among some Naga tribes, it is gifted at weddings as a symbol of sustenance.

Why, then, has the crop been overshadowed by grains like rice and wheat? Like most millets, ragi has a shorter shelf life and is harder to process. During the Green Revolution, these properties caused it to be neglected, while research, subsidies, and infrastructural investments were directed towards rice and wheat. The crop’s reputation as the ‘poor man’s food’ also meant that people aspired to move towards the consumption of rice and wheat and away from millets.

Also read: The big promise of the little millet, in Odisha and beyond

Climate resilience

Once dismissed as a “poor man’s crop,” ragi is now being championed by farmers, nutritionists, and policymakers as both a climate warrior and a nutritional powerhouse. Modern science has only reaffirmed ragi’s worth. Rich in calcium—three times more than milk—it is invaluable for bone health, especially in communities with limited access to dairy. It also contains high levels of iron, zinc, and protein, while its low glycemic index makes it ideal for diabetics. It is packed with essential amino acids like methionine and lysine that even polished rice and wheat lack. Few people realise that ragi is a rare natural source of vitamin D.

Farmers can grow it, but unless people in cities also start eating it, ragi will not survive.

Though earlier called an ‘orphan crop’ given its neglected state, its fortune is now changing. India declared 2018 as the Year of Millets, signalling its intent to put crops like ragi back into the mainstream. Yet, recognition must go hand in hand with access. Farmers can grow it, but unless people in cities also start eating it, ragi will not survive.

The climate crisis is making the case for ragi clearer each year. Floods, droughts, and rising temperatures threaten India’s food basket, even as demand for water-intensive crops continues. Against this backdrop, ragi is emerging as both a nutritional fix and a climate adaptation strategy. To invest in ragi is to invest in communities, in biodiversity, and in the possibility of a food-secure tomorrow.

Also read: Why bajra, the ‘pearl’ of India’s millets, remains underutilised

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

.avif)