Minal Sancheti

|

December 16, 2025

|

6

min read

Mumbai’s mill-era ‘khanavals’ fuelled a workforce with affordable, homely meals

Timed to mill shifts and featuring generous proportions, these meals signified sustenance and community

Read More

Pollution and urbanisation are putting an ingredient and livelihood at risk

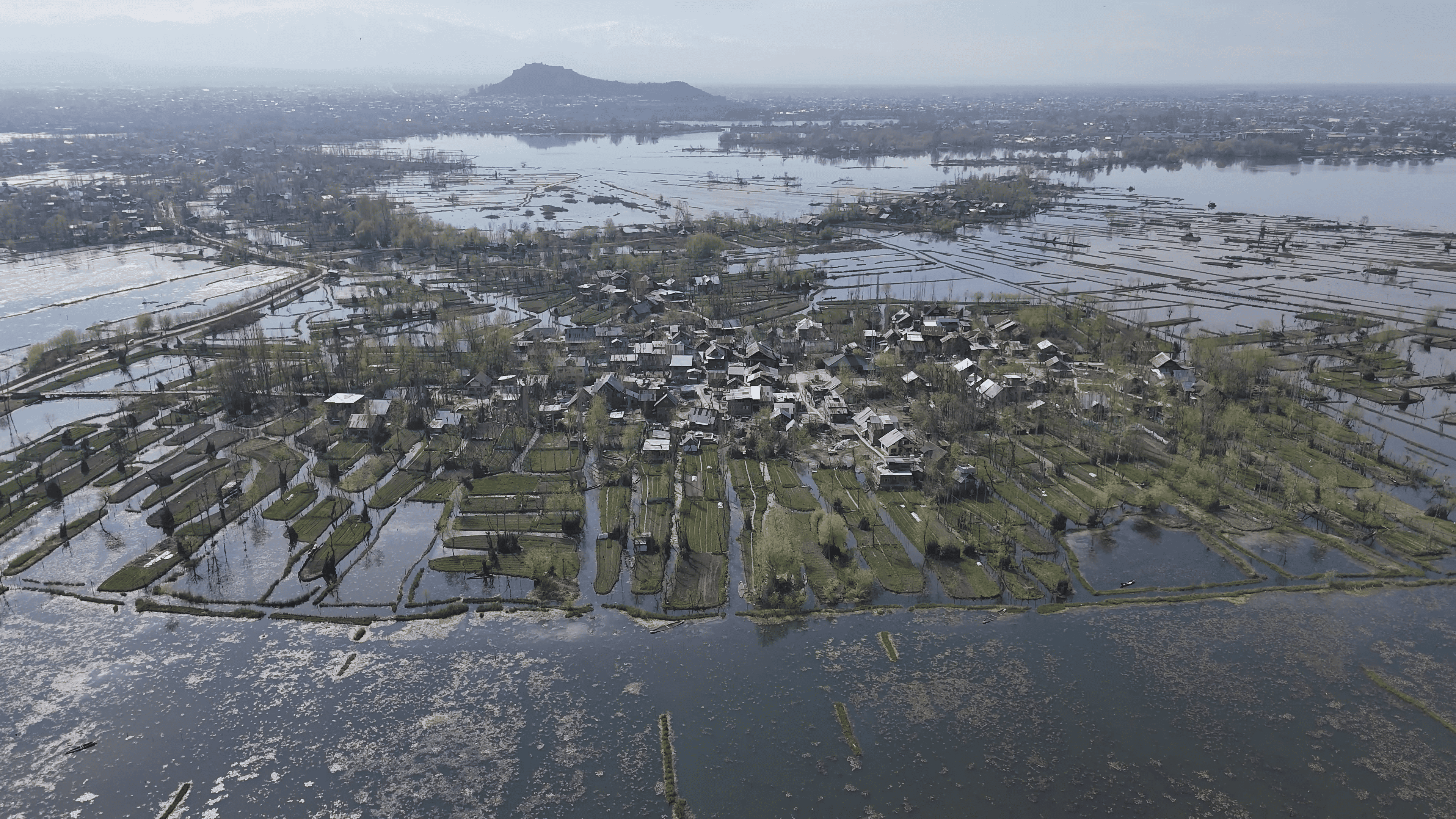

At the heart of the Kashmir Valley, where the still waters of the Dal Lake run deep, grows a humble yet special vegetable—the lotus stem. It is known as nadur or nadru/nadroo in the local tongue. The vegetable holds significance in Kashmiri traditions and cuisine—an ingredient that lends an earthy sweetness to everyday dishes, which is also treasured as a delicacy on special occasions.

For generations, farmers and fisherfolk have harvested nadur from the Dal Lake, which is nestled between the mighty Zabarwan Range and the busy city of Srinagar.

Mohammad Abbas’s family has been harvesting the crop for over 60 years. The farmers step onto their narrow wooden boats and row out into the lake's interior. Wherever the soil is hard and compact, they dive into the waters to pluck the stems manually, emerging with bundles of long, delicate white stems. When the soil is loose, they use a tool known as kaeyshum (a long staff typically made of study woods like willow and deodar, with a slightly curved end, allowing fisherfolk to gently rake the riverbed) to extract the crop. “Not everybody can wield this tool,” says Abbas with a chuckle. “You need years of experience, patience and skill. My father and uncle taught me the intricacies of this trade, which I have now passed on to my children,” he adds.

%20(1).png)

Nadur has been a source of livelihood for thousands in Kashmir. Firdous Ahmad, who has been in the business for 12 years, says that the vegetable holds a place in his heart. “This is the king of all vegetables.” But increasingly, this way of life is under threat. The Dal Lake, which once spanned over 22 sq. km, has now shrunk to 18 sq. km, and struggles against an escalating environmental crisis.

The lake is the nucleus of Kashmir’s tourism, but the fragile ecosystem it houses is now in distress. Nearly 44 million litres of waste from Srinagar, including polluted water, untreated sewage, domestic and tourist waste, and human excreta, flow daily into the Dal’s waters, contaminating them. Additionally, nearly 50,000 people reside along the lake's banks. Tourist shikaras, agricultural and domestic practices around the lake, as well as encroachments have contributed to its deterioration. Srinagar’s rapid urbanisation has outpaced the capacity of existing sewage systems. Even Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) that have been installed to treat wastewater around the Dal lake often malfunction, exacerbating the crisis.

Levels of poisonous substances like nitrates, phosphates, lead, and arsenic have crossed thresholds of what is considered safe drinking water, also poisoning the lake’s aquatic life in the process. Fisherfolk and vegetable growers who depend on the lake to feed their families bear the brunt of the lake’s slow death.

Also read: The perilous future of Kashmir's once abundant trout

Nadur farmers call for urgent action. The surrounding areas must be equipped with proper drainage systems, and nets must be installed at the end of rivulets to filter out waste, they say. The first lotuses bloom in April, and the stems mature by mid-September. After this, harvest commences and continues till the following April.

“Earlier, we could harvest around 550 bundles, or 750 kilos, from one kanal (kanal is a traditional unit of land measurement, roughly equivalent to one-eighth of an acre). Now, production has fallen by nearly 50%,” Abbas says.

Nearly Rs 23,900 lakh have been allotted to the restoration of the Dal in the last five years, Kashmir’s Home Ministry Affairs department says, but it is unclear how many of these funds have been utilised, pointing to administrative bottlenecks.

Akhtar Malik, a scientist at the Centre for Biodiversity and Taxonomy, Kashmir University, says that a bountiful harvest of nadur is an indicator of the lake's good health. Even previously, natural disasters have impacted the cultivation and harvest of these lotus stems. For instance, the floods of September 2014 disrupted the entire region around the Dal Lake, affecting marine life and vegetation, including the nadur. After more than two years, when there was still no sign of a new crop, distraught farmers plucked lotus seeds from a neighbouring lake and planted them in this region. About a year later, their efforts came to fruition when lotus stems started swaying underwater again.

Harvesting nadur is tough labour. At the break of dawn, nadur farmers dive into the frigid water—searching by touch in the murky depths. This underwater foraging requires not just skill and patience, but endurance—it is work done in biting cold, often from dawn till dusk, with harvesters spending entire days on boats without breaks.

What makes this labour even tougher today is the deteriorating quality of the lakes. Harvesters are now exposed to contaminated waters that pose serious health risks, including skin diseases, respiratory issues, and other long-term illnesses. Despite these dangers, the work continues—fewer stems, more risk, and dwindling rewards. What was once a steady, seasonal livelihood tied closely to tradition has become a test of resilience against both natural and man-made catastrophes.

Outside of the nadur season, farmers turn to vegetable fields, their hands tending to other roots. But come winter, they return to the waters, where for a day's labour under cold skies, they earn ₹1,000 and a bundle of lotus stems for themselves. Each bundle contains 15 to 16 slender, fibrous stalks, plucked with care and tied tight. Before the 2014 floods, farmers could harvest 40 to 50 bundles per day, but production has dropped significantly due to the contamination of lake waters.

Harvesters are now exposed to contaminated waters that pose serious health risks, including skin diseases, respiratory issues, and other long-term illnesses. Despite these dangers, the work continues—fewer stems, more risk, and dwindling rewards.

Also read: Why bajra, the 'pearl' of India's millets remains underutilised

Legend has it that nadur found its way into Kashmiri cuisine in the 15th century. Badshah Ghiyas-ud-Din Zain-ul-Abidin, the eighth sultan of Kashmir, was on a leisurely boat ride around the Gil Sar lake. He stopped to admire the lotuses, and his boatmen plucked their stems and added them to that evening’s supper on a whim. Today, nadur features in street food and is popularly cooked with fish, served to visitors, and consumed by families during celebrations.

The stems contain Vitamin-C and B-6, potassium, thiamine, copper, manganese and plenty of fibre, making it both a nutritious and flavourful ingredient. “Our elders say that the taste of the vegetable has changed over time, a testament to the deteriorating quality of the Dal Lake,” Afshan Rashid, a Kashmir-based food blogger says. “We also have to spend more time cleaning and peeling the stems as compared to before.”

{{marquee}}

Nadur may be disappearing from the waters of the Dal Lake, but all hope is not lost. Apart from Dal, the lotus stem also grows abundantly in several other wetlands and water bodies across the Kashmir Valley—including the Wular, Anchal, Manasbar and Haigam lakes and the Hokersar wetlands. A case study of the Wular Lake, a freshwater lake located approximately 40 kilometres from Srinagar, tells a similar story of nadur being consumed by contamination and rapid urbanisation, but then recovering and growing abundantly with the revival of the lake.

The stems contain Vitamin-C and B-6, potassium, thiamine, copper, manganese and plenty of fibre, making it both a nutritious and flavourful ingredient.

Also read: Protecting place and power, not people: The trouble with GI tags

The devastating 1992 floods of Kashmir deposited thick layers of silt across lakes in the Valley. Reports suggest that the Wular Conservation and Management Authority (WUCMA) has strategically dredged and desilted approximately 5 sq. km of the lake, especially in its Saderkoot basin. Altaf Hussain, Coordinator of Water Management at WUCMA says that desiltation was carried out between 2020 and 2023, after which authorities also sowed nadur seeds. “We are essentially restoring it to its original wetland condition,” Hussain says. Their efforts restored not just an ecosystem, but a community’s lifeline. Like a lost love returning, the pink lotuses and its stems are gracefully floating on the lake’s water again, after a nearly three-decade long absence.

This marks hope on the horizon. Similar conservation efforts for the Dal Lake, including managing the water's pH levels, preventing untreated sewage from threatening the river’s life, and a gentle revival effort can ensure that nadur blossoms in its waters again. Urgent and focused action can mean the difference between life and death for Kashmir’s culinary and ecological legacy.

Images by Muneem Farooq Itoo and Suhail Ahmad

{{quiz}}

Amid climate change and shifting diets, smoke and fire ensure nourishment

It’s a drizzly early morning in Odisha’s Sanbahali village, located in the Nuapada district. A group of seven women from the Chuktia Bhunjia community—one of India’s Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG)—are ready to head into the nearby forest. (According to the 2011 Census, their population in Odisha was approximately 12,350). Armed with bamboo baskets and umbrellas, they set off with quiet determination.

“When the rains come, we forage for wild edible mushrooms like Mala chhati, Bial chhati, Bina chhati, Banji chhati, Bali chhati, and Sargi chhati,” says 63-year-old Padma Jhankar. Locally, mushrooms are known as chhati. Not all wild mushrooms are safe to eat—some can be poisonous. “You need a sharp eye to spot the edible ones,” Jhankar explains, “We rely on traditional knowledge passed down orally through generations to identify forest foods.”

Of the mushrooms that the community harvests, Mala chhati is small, reddish, and typically found in sandy soil. Bial chhati is white and varies in size, also growing in sandy terrain. Bina chhati sprouts from termite nests—it has a long stalk with a small cylindrical head, which is white with a grayish center. Banji chhati thrives around bamboo trees; it is a creamy white with a brown spot on top. Its stalks are thin, and the body is less fleshy compared to others.

Other wild mushrooms commonly harvested during the monsoon include sargi, bali, bhuin, and kusuma. “These wild mushrooms are delicious and always in high demand,” says 37-year-old Hasila Bai from the Salepada village in Komna block. The demand comes both from locals, as well as from non-tribal outsiders, and she sells the surplus harvest in local markets to supplement her family’s income.

Bamboo shoots—locally known as kordi—are another seasonal delicacy cherished by the Chuktia Bhunjia community. Young shoots are harvested at the onset of the monsoon, between July and September. After harvesting, the tough green exterior of the shoot is removed, and the tender interior is grated into short, thin strips for cooking.

Across the past five decades, Odisha has been witness to natural calamities in 41 years—19 of which were marked by drought, according to the Odisha State Disaster Management Authority (OSDMA). Nuapada, which is among the districts most prone to this calamity, has faced severe droughts in multiple years—10 times in only 20 years, as noted in the OSDMA’s District Disaster Management Plan, 2024.

The Chuktia Bhunjia community, whose livelihood depends on rainfed agriculture—mainly paddy and millets—thus stands at the frontline of climate change. Erratic rainfall, prolonged dry spells and rising temperatures have increasingly disrupted their crop yields.

While traditional crops like millets are resilient to high temperatures and require less water, their productivity has declined, making it difficult for families to meet their year-round food needs. As a result, the community has become increasingly dependent on wild food sources to cope with food scarcity, especially during the lean season or in the event of crop failure. Today, the older generation in particular spends more time harvesting and preserving wild edibles, as farm yields have become increasingly unpredictable owing to the changing climate.

Yet, in the face of these challenges, they have adapted by turning to their traditional food preservation methods, such as smoking, sun-drying, and storing edibles in leaf bags. These practices help them build resilience, ensuring food availability during periods of scarcity.

Also read: Bastar's secret ingredient? The power of preservation

Traditionally, Chuktia Bhunjias have preserved seasonal wild edibles—such as mushrooms, bamboo shoots, and fish—using an age-old smoke-drying technique. Bamboo sticks are used to create a simple rack, on which the mushrooms and fish are carefully arranged, just above the ground. Beneath this setup, a small fire is lit to produce slow, steady smoke rather than open flames.

To ensure effective drying, a thick cloth is draped over the structure, trapping the rich, aromatic smoke and allowing it to circulate around the food. This slow-smoking process continues for several days, depending on the type of food being preserved. The result is perfectly dried mushrooms and fish that can be stored for long periods—providing both flavour and nutrition during lean seasons.

Dried mushrooms and fish are not just staples for the Chuktia Bhunjia community—they are also prized for their long shelf lives, making them essential ingredients in many traditional recipes. Sukha chhati bhaja, a stir-fried dish made from dried mushrooms, is one such delicacy that is commonly enjoyed during the winter and summer months.

“Most wild edibles are highly perishable, so we preserve them for consumption during the off-season,” says 37-year-old Jam Bai from Junapani village. For example, bamboo shoots begin to turn brown and develop a foul smell within two to three days of harvesting. To extend their shelf life, the shoots are chopped into tiny pieces and sun-dried for about two weeks to make hendua—a traditional dried form of bamboo shoots. When properly sun-dried and stored in an airtight glass container, hendua can last for two to three years, she adds.

{{marquee}}

“We preserve hendua for the winter, turning it into a chutney with tomatoes, onions, green chilies, oil and salt. It is relished with rice during winter,” says Jam Bai. The chutney tastes slightly sour and has an earthy flavour. Hendua is also sold in the local weekly markets at a price of Rs. 100-120 per kilo, she adds.

Wild edible fruits, seeds, and flowers, too—such as kendu, jujube, chironji seeds, jackfruit seeds, tamarind, and mahua flowers—are traditionally sun-dried. Once thoroughly dried, these food items are wrapped in palasa leaves (Butea monosperma) and hung above the chulha or fireplace in the kitchen. The smoke from the fireplace acts as a natural insect repellent and further enhances their preservation. “We collect jackfruit seeds, wash them thoroughly, and dry them under the sun. In summer, we boil them, peel the skin, mash the seeds, add a pinch of salt, and eat them for breakfast,” says 43-year-old Suadi Majhi from Sunabeda village.

Mangoes collected from nearby forests are also preserved in various ways, one of which is Amba Sadha—a sun-dried mango leather made from fresh mango pulp. The process begins by extracting the pulp and spreading a thin layer over a bamboo tray. After sun-drying it for two days, another layer of pulp is added on top. This layering continues until 5 to 7 layers are formed. It typically takes around 20 days for the Amba Sadha to fully dry. The final product is sweet with a hint of sourness, and serves as a cherished seasonal treat that can be enjoyed long after mango season has passed.

The age-old food preservation wisdom of the Chuktia Bhunjias is a powerful narrative of sustenance, social harmony, and sustainable living, says Pritisai Majhi, Programme Manager at Sabuja, an NGO working on the livelihood development of tribal communities in Komna.

However, he warns that these foodways are at risk of disappearing and losing their place in this tribal society.

Also read: Dried to last

According to community elders, the last two decades have seen significant changes in their food habits. “The younger generation is more inclined to eat rice, potatoes, and fried food. They are not as physically strong as our grandparents once were,” says Naratasingh Chatria, 64, Sarpanch of Junapani Panchayat in Komna block.

“Tribal foods, which are climate-resilient, culturally rooted, and highly nutritious, are still neglected and often perceived as ‘poor man’s food’ in urban areas,” said Jitendra Kumar Kar, Senior Programme Officer at Watershed Support Services and Activities Network (WASSAN), Bhubaneswar. He emphasised the need to change this narrative, which undervalues the culinary heritage of tribal communities. Kar coordinates the Coalition for Food Systems Transformation in India (CoFTI), a multi-stakeholder panel advocating for indigenous and tribal food cultures, forest knowledge, and agroecology.

Local civil society groups in Nuapada claim that the shift from a rich, diversified diet to a cereal-centric food plate has led to poor health outcomes among tribal communities. According to the Poshan District Nutrition Profile (2022), 64% of non-pregnant women in Nuapada were anemic, and 57% suffered from anemia during pregnancy (as of 2020). Additionally, 31% of women were underweight. Among children under five, 43% were stunted, 73% were anemic, and 38% were underweight. Across India, about 4.7 million tribal children under five suffer from chronic undernourishment, which affects survival, growth, learning, school performance, and future productivity, according to United Nations Children's Fund.

“Providing rice at subsidised rates through the Public Distribution System has jeopardised the community’s traditional food system, which ensured nutritional security for generations,” says Abhishek Hota, Programme Officer at WASSAN, Nuapada.

He stresses that most traditional food knowledge in tribal communities is passed down orally, and the lack of proper documentation could result in the loss of cultural heritage for future generations.

In response, WASSAN, in collaboration with tribal communities and supported by the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE), Government of Odisha has documented heirloom crop diversity, forgotten food cultures, and traditional recipes across 20 tribal-inhabited villages in Nuapada district.

“This initiative will play a crucial role in formulating better policies for neglected and forgotten food crops of tribal communities,” says Arabinda Kumar Padhee, Principal Secretary, DA&FE. Conservation and promotion of these ancient foodways will be a key intervention in the coming years. It will help diversify food systems, improve nutrition, conserve biodiversity, and safeguard Odisha’s cultural heritage, he adds.

“The traditional process of drying food using smoke and sunlight reduces moisture content, inhibits microbial growth, and prevents spoilage,” says Dr. Srikanta Dhar, a specialist at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bhubaneswar. He notes that uncultivated and wild edibles foraged by tribal communities significantly contribute to their intake of calcium, iron, essential minerals, and vitamins. However, he cautions that proper identification, purification, and storage are essential before consumption. In the past, there have been reported cases of tribal deaths caused by consuming improperly prepared mango kernels, as well as poisonous mushrooms or bamboo shoots.

The traditional food practices of the Chuktia Bhunjia are more than just survival strategies—they are a testament to resilience, cultural continuity, and ecological wisdom.

Also read: In rural Odisha, the Juang community's seeds are gifts from ancestors

In a pot, boil water. Add the dried mushrooms and cook for about 30 minutes on medium flame. Add salt and turmeric powder to enhance the flavour. After boiling, drain the excess water.

Heat oil in a pan over medium flame. Add chopped onions, garlic, and grated ginger. Sauté until the onions are translucent and fragrant. Add chili powder, cumin powder,turmeric, and salt to taste. Mix well to blend the flavours.

Add the boiled mushrooms to the pan. Stir everything together and cook for another 20–25 minutes, allowing the flavours to meld. Once cooked, serve hot with rice or chapatis.

Edited by Anushka Mukherjee and Neerja Deodhar

{{quiz}}

Did you know this mighty macronutrient plays a role in hormones and brain chemistry?

Editor's Note: From grocery lists, to fitness priorities, and even healthy snacking, protein is everywhere—but do we truly understand it? In this series, the Good Food Movement breaks down the science behind this vital macronutrient and its value to the human body. It examines how we absorb protein from the food we consume, how this complex molecule has a role to play in processes like immunity, and the price the Earth pays for our growing protein needs.

Humans, like many creatures in the animal kingdom, have what scientists call a “dominant appetite” for protein. Insects make this drive look dramatic: a cricket low on protein will turn cannibal; a locust, when deficient, will roam until it finds other food sources that restore balance.

Humans fall somewhere in between. When offered a diet heavy in carbs and fats but light on protein, we tend to overeat out of an unconscious effort to meet our protein needs. Biologically, protein is essential: it’s the only macronutrient that contains nitrogen as part of its core structure, which our bodies need to grow, repair, and reproduce.

By now, we recognise that protein matters, but its presence in meals means different things to different people. To some, it’s synonymous with weight loss. To others, it’s about building strength. However, beyond this well-known understanding, proteins are doing invisible work that is crucial to our body.

Among all the macronutrients, protein is the most thermogenic macronutrient—your body burns more calories breaking it down than it does for fats or carbohydrates.

Also read: Is your body low on protein? Signs and impacts of a deficiency

Also read: Whey to go: A complete guide to protein

{{quiz}}

Their secret sauce? Procuring ingredients with care and cooking them without rush

Sun-kissed vegetables, slow-roasted meat, aromatic steamed rice—there’s something invigorating and comforting about every bite of food served in the ‘Mei Ramew’ (Mother Earth, in Khasi) cafés of Khweng. Every ingredient carries a flavour that is distinctly unique to the corner of Meghalaya where the cafés are located.

Standing side by side, these two establishments are more than just places to eat traditional Khasi food. They are an initiative aimed towards giving the region's rich agrobiodiversity a spot on local plates—encouraging the Khweng community to keep their ancestral Khasi cooking traditions alive, and also empowering them with a livelihood.

“We never cook anything in a rush,” says Kong Plantina.

Many chefs and cooks hold their secret ingredients close to their hearts. Some recipes are passed down through the family, while others take these secrets to the grave. However, Kong Plantina Mujai and Kong Dial Muktieh, who run the two cafe outlets, are generous in sharing details about what makes their cooking magical.

“We never cook anything in a rush,” says Kong Plantina.

The secret ingredient or recipe behind the Mei Ramew cafés’ nourishing food is simply–time. Time taken to organically grow and procure fresh produce; and to cook the food with care and a sense of deliberation, that renders it its wonderful flavour.

The philosophy of the Mei Ramew Cafes is a reflection of the larger Khweng community. For the people of Khweng, food is their identity and they regard it as something that cannot be rushed—whether you’re growing it or cooking it.

Also read: Let there be light, where the grid cannot go

Khweng wasn’t always like this. In the early 2010s, it was one of many villages in Meghalaya that had been affected by the craze for monocropping and commercial farming, which affected both soil health and the community whose livelihoods depended on the land’s produce. Conversations with the villagers reveal that they used to use chemical fertilisers in their fields earlier. In 2012, the North East Society for Agroecology Support (NESFAS), a Meghalaya-based NGO, started collaborating with Khweng for a vital mission: to safeguard indigenous food systems and reintegrate local ingredients and the agrobiodiversity of the village into their meals. They taught Khweng’s farmers composting and organic cultivation methods focussed on local plant species rather than mainstream, commercially-viable crops.

At the heart of this initiative was Kong Plantina Mujai, a woman renowned for her expansive knowledge of local ingredients and traditional methods of cooking—skills she had honed since 1993. In 2013, NESFAS established the first Mei Ramew café in Khweng for Kong Plantina to kickstart this initiative which would blend ancient wisdom and financial prospects for the community.

“The essence of the Mei Ramew café is to have clean, organic food. Food that we get from nature,” she says, chopping a bunch of water celery while keeping a watchful eye on the rice she’s steaming in the klong [bottle gourd shell].

“We wanted to celebrate the taste and diversity of local food. Opening a café seemed to be the most logical course of action. This would also generate more livelihoods for the people of Khweng,” shares Janakpreet Singh, Senior Associate, Livelihood Initiatives at NESFAS, about the origins of the Mei Ramew cafés.

Two years later, Kong Plantina’s Mei Ramew café became a sensation during the Indigenous Terra Madre event hosted by NESFAS in 2015. Indigenous communities from over 52 countries participated in this event. The success of her café further incentivised NESFAS and the community to scale the Mei Ramew initiative. In 2019, NESFAS helped transform Kong Dial Muktieh’s food stall, which has hitherto served local snacks and traditional Khasi food, into Khweng’s second Mei Ramew café.

The two women behind the Mei Ramew cafés are their very heartbeat, shaping every facet of the way they are run. Each brings a distinct perspective and personal style to their approach to cooking.

For Kong Plantina, who regards her grandmother as her inspiration for cooking, food is all about putting love and time into meal prep. Her special bond with her grandmother shines in the many recipes and kinds of cuisine she has inherited from her. Having cooked for more than three decades now, she has improved on many of the familial recipes while also coming up with her own dishes. One meal she is famous for is a local fish recipe cooked with black pepper and sawtooth coriander.

“The essence of the Mei Ramew café is to have clean, organic food. Food that we get from nature,” she says, chopping a bunch of water celery while keeping a watchful eye on the rice she’s steaming in the klong [bottle gourd shell].

{{marquee}}

It is the weekend when this writer has visited her–and most of the tables in her café are occupied. At its full capacity, the café can serve about 20 people. One lucky group enters and occupies the last table. They place an order for her special grilled fish and Jadoh [rice and pork] and are promptly attended to by her daughter.

Unlike the early days of the café when she ran everything herself, Kong Plantina’s daughter is now learning the ropes of running the café and helping the business grow. In truly indigenous fashion, the art of traditional cooking that she polished over years of experience and by sitting at her grandmother’s side are now being seamlessly passed on to her daughter.

On the other side of the road, Kong Dial Muktieh is busy grilling a batch of pork on iron skewers. The skewers and some steel pots are some of the only modern cooking instruments in her kitchen. Kong Dial Muktieh emphasises on traditional methods of cooking. Various traditional ingredients and methods of preparation that have disappeared from Khweng’s meals over time, make their return to her kitchen momentous.

A mapping on wild edible plants conducted in 2021 in Ri Bhoi district revealed that Khweng had the highest agrobiodiversity in Meghalaya with over 319 micro-nutrient rich and climate resilient crop species.

Chopped fish and wild edibles boil inside bamboo poles on the fire, while an assortment of cherry tomatoes, bitter brinjal and banana flowers are covered with broad wild leaves and buried in hot ash. On the other side of the fireplace, rice cooked in bamboo poles is ready to be served to hungry customers with side dishes of sweet and tangy rosella, bamboo shoot with fish amongst others. There are more than 20 side dishes in the special Khasi thali. Local wines made from rice and fruits are also served in bamboo cups.

Inside her kitchen, you’re transported to a different time. These aren’t fancy urban restaurants trying to recreate traditional recipes in commercial kitchens: these are warm, comforting hearths where the soul of traditional cooking is being kept alive.

Also read: How lemon groves turned Manipur’s Kachai into a citrus empire

Today, Khweng is a self-sufficient community–where indigenous food systems provide sustenance to the village all year-round. This can be attributed to the organic methods of farming as well as the identification, popularisation and foraging of wild edibles and plants such as fishmint, Indian pennywort, and water celery, which all boast a high nutritional content (potassium, iron, magnesium, zinc and Vitamins A, B and C among others). A mapping on wild edible plants conducted in 2021 in Ri Bhoi district revealed that Khweng had the highest agrobiodiversity in Meghalaya with over 319 micro-nutrient rich and climate resilient crop species.

The Mei Ramew cafés stand as a collaborative effort: several farmers in Khweng sell their surplus produce to these establishments, sustaining themselves as well as the cafés. “I supply different vegetables, fish and chicken from my farm and this has helped me earn an honest living for my family,” shares Pistar Nongktieh, one of the suppliers at Kong Dial’s café.

The use of many wild edible plants in the two cafés has also revitalised a curiosity for traditional Khasi cuisine. It has encouraged Khweng’s residents to incorporate these vegetables into their daily diets, enhancing their dietary intake and health. “These two cafés have brought many benefits to the villagers,” shares Rikuna Nongsiej, a farmer from Khweng who supplies her produce to both cafés. “We have put Khweng on the map, thanks to these two cafés,” she adds, smiling.

On the drive back from Khweng, a remark made by NESFAS’ Singh stays with this writer. “Promoting local and indigenous food was a completely new idea when we started this initiative. Khweng’s people truly took on this challenge with courage and curiosity. Today, the fact that these cafés have a loyal clientele and are successfully generating livelihoods and attracting visitors, is amazing. All credit goes to them.”

Mei Ramew cafés also reflect the ingenuity and resilience of indigenous communities in the face of adversity. At the heart of it all are the community’s women, who are often considered the custodians of biodiversity, seeds, and cultures. In the face of mounting food crises around the world, Khweng’s Mei Ramew cafés highlight the oft overlooked strength of indigenous food systems, which can offer scalable, resilient solutions rooted in tradition and sustainability.

Also read: How the 'makrei' sticky rice fosters love, labour in Manipur

Images by SC Horzak Zimik and NESFAS.

{{quiz}}

Despite its nutritional content and climate resilience, it is overshadowed by paddy, wheat–and even ragi

On the banks of the mighty Chambal in Rajasthan’s Dholpur district, Devi Jadon is hard at work in a field. The local, marginal farmer, who is a resident of Shankarpur village, has her eyes set on the cultivation of pearl millet—or bajra, as it is familiarly known.

Jadon sows the seeds in the Kharif season–June to September–and welcomes nourishment from the monsoon rainfall in this semi-arid region. The labour she puts into bajra’s cultivation is mainly meant for household consumption in the winter. The leaves and stalks of the harvest are fed to cattle. Only in case of excess production is the crop sold in the local market. Come Rabi season, and she focuses on wheat and mustard.

Pearl millet is grown extensively in Rajasthan, which is the largest producer of this grain across India. It is cultivated in about 25 villages across the Jhiri and Madanpur panchayats of Dholpur–a district characterised by deep ravines.

Since millets originally evolved in the arid and semi-arid regions—much before modern irrigation—where they are still cultivated, the crops require very little water: 33% less than rice. The pearl millet, in particular, has high photosynthetic efficiency as well as high dry matter production capacity; it can be grown under even the most adverse conditions, like high temperature, and in shallow, infertile soil with poor water retention—regions where other crops like sorghum and maize simply cannot thrive.

Generally, monsoon showers are adequate for the pearl millet, since the crop—much like its relatives in the millet family—is suitable for dry conditions. “It is able to withstand extreme heat and drought, and can be grown with low inputs,” says Pradeep Kumar, a scientific officer in pearl millet breeding at the Hyderabad-based organisation, International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics (ICRISAT). They conduct research on dryland agriculture, especially millets.

The pearl millet has short development stages and a capacity for a high growth rate, too. Most millets can withstand the vagaries of climate change, but pearl millet really takes the cake: it requires even less water than ragi (red finger millet). Agricultural experts and researchers like Kumar realise the importance of bajra, which is also grown in the summer in the Jalore-Sanchore belt of western Rajasthan. “It is really the pearl of the whole millet basket of India,” explains Bhagirath Choudhary, the founder-director of South Asia Biotechnology Centre–a non-profit that works in bio-innovation. “In winter, it is a staple food for many.”

The terrains of Northern India lend themselves suitably to the cultivation of millets (along with some parts of sub-Saharan Africa), and thus it comes as no surprise that India is the largest producer as well as exporter of millets in the world. The pearl millet has the dominant share in this production. In the year 2021–22, the crop generated 58% of the total millet production, followed by sorghum (29%) and finger millet (10%). It occupies around 75 lakh hectares of cultivation area in the country, most of it in the Kharif season.

Despite lacking ragi’s perceived superior position in the millet family–as well as the popularity of paddy and wheat–bajra has survived.

Besides Rajasthan, where temperatures soar to as high as 50°C in summers, farmers grow pearl millet in western Uttar Pradesh—a region that is unfit for paddy. It is also cultivated in Haryana and Andhra Pradesh; the drought-prone Rayalaseema region of AP is known for bajra cultivation. According to Borra Srinivas Rao, who works at The Buddha Institute and is based in Hyderabad, the policy of subsidised rice has changed millet consumption considerably across India. PV Suresh Kumar, an independent researcher and development consultant who works on millets, explained that paddy is the dominant crop in Andhra Pradesh, which has a significant share of wetlands. “Though bajra was common in the tribal areas, many farmers have now turned to turmeric, chilli and coffee,” he says.

Also read: ‘Summer ragi’: How Kolhapur farmers’ millet experiment became a success story

Millets, as a family of ancient cereals, garnered notable attention during and after the United Nations declared 2023 to be the International Year of Millets in 2023. However, a bird’s eye view of the promotional efforts and schemes around millets that followed suggests that much of the limelight has been shone on ragi, which is known to be rich in nutrients like calcium. Bajra lagged behind.

Tara Satyavathi, Director of Hyderabad-based Indian Institute of Millets Research, agrees that the pearl millet has not garnered as much attention as ragi. “Whereas bajra is grown on 7.5 million hectares, ragi occupies about 2 million hectares. But the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for ragi is higher than that of bajra. A higher weightage is given to ragi; ragi mudde is consumed in Maharashtra and Karnataka.”

This report tracks the rise in MSP of various millets across the last eight years, and shows that bajra’s MSP had a slow crawl compared to ragi. In 2024-25, ragi’s MSP rose by over Rs. 400 per quintal, whereas that of bajra increased only by Rs. 125 per quintal. As an example, the Odisha Millets Mission pressed on massive procurement of ragi over bajra. Even at the centre, the procurement of pearl millet remains lower than that of ragi, at just 1-3% of the total production.

One of the reasons is perhaps that atta or flour derived from pearl millet cannot be stored for a long time. “Bajra atta has to be prepared fresh using the traditional chakki, a hand-driven millstone, at home every two days to make chapatis. It cannot be stored for more than five days, as it turns rancid,” Jadon explains. However, the pearl millet has superb nutritional properties: it is especially high in iron and zinc content. Just like other millets, pearl millet, too, is gluten-free, rich in fibers and amino acids, is non-allergenic and has a low glycemic index.

Choudhary, a Jaipur resident, points out that though Rajasthan is the largest pearl millet producer in the country, the crop is not procured from mandis or market places by the state government. “It is most unfortunate. In Rajasthan, farmers grow bajra as an important cereal crop. Yet, it has not received recognition. The consumption of pearl millet, however, reflects in the nutrition profile, such as the height and the build of people who regularly eat it,” Choudhary says.

In Rajasthan, its production occupies about 4.43 million hectares of land. Many smallholder farmers like Jadon depend on the pearl millet, but it is sold at low rates in the market. Jadon gets Rs 20–Rs 23 for one kilo. The minimum support price in 2024-25 for pearl millet stands at Rs. 2,625 per quintal–that would assure at least Rs. 26 per kg, but Jadon is reduced to selling it for a lower price.

The consumption of pearl millet, however, reflects in the nutrition profile, such as the height and the build of people who regularly eat it,” Choudhary says.

A couple of forces come together to tug at bajra’s market price: to begin with, the overall demand for millets remains low. It fell by 67% in urban and 59% in rural areas between 1972-73 and 2004-05, according to this report. Owing to the rise in production (and consequent fall in prices) of staples like wheat and rice, the contribution of millets and maize to the average Indian’s cereal requirements dove from 23% to 6%, by 2011. In the last few years, central as well as state governments have successfully tried and mitigated this, by promoting millets meaningfully.

And yet, a major problem has now arisen: this new value chain of millets is breaking. While new millets-based products have entered the market, they cost more than their maida-based counterparts; this is because the storage and processing cost of millets is higher, and thus the margins in this business are higher. The demand for these products is also inconsistent, and so the processors have to accommodate for this in their costs. The result: these prices do not reach the farmers, and eventually urban as well as rural consumers do not want to pay a high price for millets in the market. The farmers have no choice but to sell their bajra at rates lower than the MSP.

Though the MSP is fixed by the Centre, procurement happens at mandis which are controlled by state governments. “The state government has to take a stand for pearl millet,” Satyavathi says.

Despite lacking ragi’s perceived superior position in the millet family–as well as the popularity of paddy and wheat–bajra has survived. The crop continues to hold an important place in regional cultures and food habits. It is also common to consume this millet in the form of bajra malt or porridge. From the Anantapur district of Andhra Pradesh, to villages in Rajasthan, pearl millet flour is used to make rotis/chapatis. “My mother still makes bajra chapatis, but it is difficult to prepare them. As bajra is gluten-free, it lacks the elasticity of wheat. Making the dough requires skill,” Choudhary adds.

Besides chapatis, Jadon makes a dish with jaggery, sesame and bajra atta. The ingredients are mixed into a dough and shaped into small balls–akin to the ‘bati’ in dal-bati-churma. The balls are then roasted in an oven. When guests arrive during the harvest season, Jadon also serves bajra grains roasted in an open fire, as a snack. In western Uttar Pradesh, where the pearl millet is a key crop that thrives in less than even 150 mm-200 mm rainfall, it is valued during the Makar Sankranti festival when people make laddoos from roughly ground flour.

But the story of the pearl millet in India is much, much older. Mughal emperor Jahangir, in his autobiography Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, raves about the delicious ‘lazizi’: a khichdi of boiled peas and bajra that he encountered in Gujarat. Millets also find a place in religious rituals and festivals; while the Kuthiyottam festival in Kerala celebrates the harvest of millets, bajra is offered to gods in Rajasthan. In many parts of the country, millets are associated with fertility and prosperity.

To this day, folk songs in Rajasthan celebrate the bajra. There is a saying that goes like this in Marwari: ‘Jinki khao bajri, Unki bajao haajri’ (if someone feeds you bajra, you must oblige them).

Bajra contains invaluable nutritional properties–and it is, without a doubt, among the cheapest sources of protein in India. This ancient millet has a well-deserved place not only in our Public Distribution System and processed food value chains, but also in our everyday diets at home.

Also read: One Odisha woman’s mission to preserve taste, tradition through seeds

Cover image: Wikimedia Commons/Shanmugamp7

{{quiz}}

How to troubleshoot and bring your pile back to life

Editor's Note: In this series, the Good Food Movement explores composting—a climate-friendly, organic way to deal with waste. We answer questions about what you can compost, how to build composting bins and how this process can reshape our relationship with nature and our urban ecosystem.

Setting up a compost bin from scratch is exciting, but when things go wrong, it can feel like a soggy, smelly disaster. Whether you're composting on your terrace, in your backyard, or using a kitchen composter, it’s normal to encounter these problems. Here's how to troubleshoot the most common hurdles and get your compost back on track:

A healthy compost pile should smell earthy, like fresh soil after rain. If your compost smells like sewage or ammonia, it's usually a sign of too much nitrogen-rich "green" material (such as vegetable scraps or cooked food) and not enough carbon-rich "browns" (like shredded paper or cardboard). A rotten egg smell, on the other hand, typically means there's too much sulphur and poor air circulation or excess moisture.

The solution:

A quick way to check compost moisture levels is the fist test: Grab a handful and squeeze. If water runs out, it's too wet—turn the pile to dry by adding more browns. If you see just beads, moisture is ideal. If it's dry, add a little bit of water. Mix well and repeat as needed.

Turn your compost immediately using a garden fork or stick. For every handful of wet kitchen waste, add two handfuls of brown materials—shredded newspaper, cardboard, coconut husk, or dried leaves. Aim for a 3:1 ratio of brown to green materials. If you're using a closed bin, drill more holes for ventilation. Also, stir the compost every few days to aerate it. Lastly, avoid cooked food or dairy unless you're using a composter (electric food recyclers quickly turn your kitchen scraps into nutrient-rich plant food by creating ideal conditions for organic matter to break down and for helpful microorganisms to thrive), which can handle it better.

Also read: Don't dump it, compost it -- Why peels and scraps shouldn't be tossed into your garden

Nothing kills composting enthusiasm faster than some uninvited visitors – be it a cloud of flies greeting you every time you lift the lid, or worse, rats. This is caused by exposed food scraps, especially fruit peels or meats, oil or bones. If you see ants trailing through your compost, it is a sign that it is too dry, as ants like to find dry soil for nesting.

The solution:

Always bury fresh kitchen scraps under a layer of brown materials. This smothers odours and keeps the pests away. Keep a container of dried leaves, sawdust, or cocopeat nearby for immediate covering. Avoid adding meat, dairy, or oily foods entirely.

If flies persist, use some lemongrass spray, or lay a piece of jute cloth over the surface. Use a lid or cover if you’re composting in a bin. A simple piece of cardboard or jute sack will do.

Also read: Setting up a compost bin at home: Do's and don't for feed and airflow

During monsoon season, outdoor compost piles can turn into a waterlogged mess. Plus, kitchen waste naturally contains high moisture. Too much water can lead to a pile that decomposes anaerobically (without air), leading to rot instead of compost.

The solution: Add more brown materials immediately so the compost pile can absorb excess moisture. If your pile is outdoors, cover it with a tarp or corrugated sheet during heavy rains. For balcony composters, ensure proper drainage. Avoid dumping large amounts of wet or juicy scraps—like melon flesh or overripe fruits—all at once. Chopping vegetable waste and draining liquids before tossing greens into the pile is always a good idea.

Waiting months for compost can test anyone's patience, especially when space is limited in urban Indian homes. Oxygen-loving microorganisms break down organic matter in your compost pile, using it as fuel for their cellular processes and generating heat in the process.

Heat is imperative for your waste to eventually turn into compost.

So what causes the compost to not heat up? The pile is too small (under 3’x3’, or 5’x5’ in winter), too dry, low in nitrogen, or lacking in air flow. The most common one is dryness.

The solution: Turn the pile to mix the materials in your compost pile. While turning the pile, add water. Let the pile rest for several hours, then give it the fist test again.

Furthermore, kitchen scraps (containing nitrogen) need plenty of dried materials (containing carbon) to balance things out. Turn your pile weekly, or use a long stick to poke holes for aeration in smaller bins. During winter, place your composter in a sunny spot to warm your compost pile and maintain its core temperature. In summer, provide some shade and maintain adequate moisture by sprinkling water if the pile feels dry.

Also read: The science of scraps: How to get composting right

Chop your waste into small pieces as they decompose faster. You can also add a compost accelerator, be it a handful of old compost, garden soil, or cow dung.

Most composting problems stem from disturbing the balance of air, moisture, nitrogen, and carbon in the pile. The first step to fixing the problem is to observe which factor is out of place. The more you observe your compost bin, the better you will be able to detect issues that will invariably pop up for anyone composting—whether you’re a novice or a veteran.

Edited by Durga Sreenivasan and Harshita Kale

{{quiz}}

While hair loss and fatigue are more visible signs, a protein deficiency can also affect the body’s muscle reserves

Editor's Note: From grocery lists, to fitness priorities, and even healthy snacking, protein is everywhere—but do we truly understand it? In this series, the Good Food Movement breaks down the science behind this vital macronutrient and its value to the human body. It examines how we absorb protein from the food we consume, how this complex molecule has a role to play in processes like immunity, and the price the Earth pays for our growing protein needs.

If you observe a lot of sudden hair loss, or if your nails look dull and chip every time you try to open a jar or can, you may want to sit up and take notice. Brittle hair and nails, if co-occurring and sustained, are often the first indicators of a protein deficiency.

Protein is part of every activity your body undertakes—the flutter of an eyelid, the contraction of a muscle, or the diffusion of oxygen into our cells. Hair, nail, and skin problems are usually the earliest manifestations of a protein deficiency. Proteins like keratin, collagen, and elastin make up skin, hair, and nails. When the body has limited reserves of protein, it prioritises tasks like tissue repair and is unable to perform other tasks—which in turn, show up as symptoms. In hair, this could result in thinning and hairfall. Similarly, nails could develop ridges and become more prone to breaking. Bereft of nourishment, your skin could become dry and flaky, or prone to acne, and melasma.

Another sign to look out for is feeling hungrier, especially if you are craving something sweet. Proteins decrease the level of ghrelin—the ‘hunger hormone’ which contributes directly to you feeling full and satiated. Thus, a protein deficiency can allow hunger pangs to thrive unfettered. Our bodies digest protein very slowly. When we consume a meal high in carbohydrates, without consuming enough protein to counterbalance them, our meal gets digested faster, resulting in a spike in blood sugar levels. This sharp spike is followed by a drop, and these fluctuations can make us reach for that bar of chocolate more often.

If the body's protein needs are consistently unmet through external sources, the body turns inwards towards one of its final reservoirs of protein: our muscles. Unbeknownst to us, our bodies may start breaking down muscle mass for essential functions like creating essential enzymes or repairing tissues. As your body chips away at muscle mass, it saps your strength, leaving you perennially exhausted. This can worsen if, despite using muscle mass, the body is not able to create enzymes important for digestion or nutrient absorption in a timely manner. The fluctuation in blood sugar levels also means that the body is unable to sustain energy levels through the day.

If the body's protein needs are consistently unmet through external sources, the body turns inwards towards one of its final reservoirs of protein: our muscles.

Some protein deficiencies can also cascade into other ailments. For example, if the body is not able to produce enough globins [a kind of protein involved in oxygen transport], then it is unable to produce sufficient haemoglobin despite having adequate iron. Thus, a protein deficiency can also cause anaemia. In anaemia, the red blood cells do not have adequate haemoglobin resulting in poor absorption of oxygen, and consequently, weakness.

These reasons—the body tapping into its internal reserves of muscle mass, the untimely production of enzymes, the fluctuation of blood sugar levels, and deficiencies in turn leading to other ailments—merge to result in the most insidious symptom of protein deficiency: chronic fatigue.

Also read: Whey to go: A complete guide to protein

With each step, the body is forced to choose which part of its upkeep to compromise. Beyond hunger, hair, and fatigue, indicators of a deeper deficiency surface, says Mumbai-based dietician Dr. Afsha Sheikh. Hereon, injuries are slow to heal, muscles ache persists, and antibodies find themselves far too outnumbered to oust pathogens. Bone tissue too grows brittle, increasing the risk of fractures from simple acts like jumping or dancing. The combination of slow recovery and poor immune response make the body vulnerable to frequent injuries and illnesses without being able to recuperate fully.

When broken down chemically, proteins are made up of amino acids. Some of these amino acids are necessary for the production of neurotransmitters. Their absence could result in lesser serotonin and dopamine production. Often termed the ‘happy hormones’, these neurotransmitters help regulate functions like mood and sleep, and their absence affects emotions as well as cognitive function.

The internet is teeming with advice, and it can be tempting to self-diagnose a protein deficiency. It is important to remember that our bodies don’t process nutrients in isolation, and that the same symptoms can surface as a result of different or overlapping deficiencies. If you spot any milder symptoms—like your hair and nails growing brittle—for over a fortnight, consult a dietician first, says Sheikh.

Addressing these symptoms rather than writing them off is crucial to catching any deficiency in time. If you already have the more severe symptoms like chronic fatigue and slow-healing injuries, then it is important to consult a physician first, and then work alongside a dietician.

Also read: Eating healthy: Is take-out cheaper than cooking at home?

{{quiz}}

After years of hard work, Kerala’s P Bhuvaneswari continues to till the land instead of merely supervising

As a young child, Kerala-based P Bhuvaneswari farmed with her father, Kunjikannan Mannadiyar. She fondly remembered the quiet satisfaction that came from working in the fields, and carried these memories well into her adult life—she knew that one day, she would want to return to tilling the land.

In 1995, Bhuvaneswari’s dream came true, but not quite: her husband Venkidachalapathy came into a share of ancestral property in the Elapully panchayat of Palakkad district. Venkidachalapathy, having served as both a math teacher and principal at the Government Moyans HSS, retired; the couple decided to move from the city to a life of farming. There was one major hurdle: whereas soil in Palakkad usually has a pH between 7 and 8.5, her land was inhospitably acidic, with a pH of 4.8. The land was bone-dry, filled with rocks, and stubbornly refused to nurture plants or yield water.

But Bhuvaneswari would not give up. First, she and her son Sajith cleared the land of stones, weeds, and bushes. Then, she consulted veterinary surgeon Dr Shudhodanan. She learnt that the way forward was to replenish the soil, so she planted some seema-konna (Gliricidia). Gliricidia is a miracle crop that grows rapidly and well, even on degraded soils, and increases soil fertility by around two to three times. While the soil healed, the family had to find a way to sustain themselves in the interim. At this point, a loan came through, providing two cows and a regular source of income in the form of milk. Moreover, cow dung served as organic manure and further enriched the soil. Gradually, Bhuvaneswari began planting mango trees, interspersed with turmeric first, and then ginger. Once these plants had put down roots, she experimented with other plants, including jasmine.

But she was yet to face her biggest challenge: arranging water for the crops. “When I started this farm, everyone told me it was a foolish idea because I would not get anything from it. ‘There will be no rain or groundwater,’ they said.” The naysayers were not all wrong; Bhuvaneswari dug two to three wells, but to no effect. Eventually, she dug a borewell over a kilometre away from her farm. It worked, and a second borewell soon followed.

In present times, 65-year-old Bhuvaneswari has adopted a high-density farming technique—not an inch is left uncultivated.

With a water resource in place, it was a matter of patience and faith. Five years were to pass before her persistence was rewarded, and Maruti Gardens came to life. Before long, she was planting two crops of paddy annually, and one crop of sesame, urad dal, horse gram, and moringa in between as cover crops. As her farm thrived, so did her children; they secured jobs in foreign countries. Having watched the happiness their mother derived from farming, they purchased 20 acres of land surrounding the original 4.5 acres for her.

{{marquee}}

In present times, 65-year-old Bhuvaneswari has adopted a high-density farming technique—not an inch is left uncultivated. Mango, jackfruit, areca, plantain, tapioca and coconut trees line her land, providing bountiful returns. Beyond native varieties of jackfruit, she is also growing the rare Vietnam early jackfruit that bears fruits within a year, as compared to other varieties that take between three to seven years. She also grows dwarf jackfruit trees, interspersing them with turmeric. A dedicated ten-acre space is set aside for rice cultivation, involving both Uma and ASD (Ambasamudram) paddy varieties. It yields upwards of 25 quintals annually.

Having sustained her farm for five years through dairy, Bhuvaneswari invested amply in animal husbandry. Her farm has cows of five varieties: Kapila, Vechur, Kangavam, Gyr, and a native breed. Hens, ducks, dogs, and goats can also be spotted around Maruti Gardens. Two acres are set aside for two massive fish ponds which rear catla, tilapia, and rohu fish.

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

When Bhuvaneswari had nothing but barren land and iron-clad determination, she found direction through a workshop by Subhash Palekar. Palekar is an agriculturist and Padma Shri awardee who propounded the “Zero-Budget Natural Farming” method. In the mid-1990s, it emerged as a low-cost alternative to the input-heavy methods brought about by the Green Revolution.

To this day, Bhuvaneswari maintains that she owes her farm’s success to her adherence to old farming techniques; that small measures—such as using dry leaves as mulch rather than burning them—go a long way. Having witnessed the results yielded by organic farming, she is pained to see the continued use of fertilisers like urea that hurt soil strength. She prepares her own bio-fertilisers, such as Jeevamrutha, Beejamrutha, and Panchagavya using cow dung and urine. “We grind 16 leaves in a stone bowl and put them in an earthen pot placed inside the soil. We then take the pot out after 41 days, strain it, and bottle the mix before we start cultivation.” This liquid is then applied to all plants as a natural pesticide. She is now an active member of Jaiva Samrakshana Samithy, Kerala's State Biodiversity Board.

Even in her mid-sixties, she prefers to participate in farming activities rather than merely supervise. She can usually be found up before dawn, engaging in tasks like ploughing the land, sowing seedlings, or even drying turmeric to turn it into powder. She operates a tiller with ease, having learnt to do so from her father. Faced with the issue of irregular farm labour, she also taught herself to drive a tractor a few years ago.

In 2021, she won the Malayala Manorama’s ‘Karshakasree' (best farmer) award. Beyond recognition and awards, there is a sense of spirituality to how Bhuvaneswari views farming. Every season of sowing and harvesting is marked by a pooja (prayer). Not once will she be caught wearing shoes while walking through her farmland. “With footwear, I feel like I am moving away from nature,” she says.

Even in her mid-sixties, she prefers to participate in farming activities rather than merely supervise.

When she started selling her produce online, she branded herself as 'Ammachi,' and her store as 'Ammachi's Organic Farm.' Translating to 'mother' in Malayalam, the term ‘Ammachi’ represents the maternal nature of her relationship to all that she grows. Perhaps, it also extends to those she grows it with. "My workers are like family to me, and we always work together on the fields like a team," she says.

Her kindness extends into other avenues: she is a much-loved volunteer at the Sneha Theeram Palliative unit, a local NGO. During the COVID-19 lockdown, she would get a 100 lunches packed every day and place them on her house's compound wall for those in need to collect. “There were many in dire straits in our neighbourhood. By providing them one meal, at least some of them did not have to go hungry,” she says in reflection. She continues to provide relief kits and meals to old age homes and those who are unwell.

Her affable personality has drawn in people from all walks of life, leading to the establishment of farm tours, as well as farming lessons conducted both online and in-person.

Also read: Babulal Dahiya makes every grain of rice count

“All my life, I’ve heard that agriculture is not profitable. But this is not true in my case,” Bhuvaneswari shares. Profitability comes with strategy, and Bhuvaneswari’s strategy was two-pronged: First, diversify from farm products (like fresh fruits) to farm-based value-added products (like pickles). Second, take ownership of your supply chain.

Most of the farm’s produce leaves its quarters in an entirely different form. Jackfruit is turned into either papadam (papad) or kondattam (sun-dried fruit that is fried subsequently). Coconuts, for the most part, transform into coconut chutney powder. Some of them, however, get to spend some time in earthen vessels as they become cold- or hot-pressed coconut oil. Plantains are prepared into sharkara varatti (jagerry-coated chips) or plantain powder (a substitute for flour). Rice is made into idiyappam, puttu, idli, and avil (flattened rice). Ghee is a key ingredient for preparing the bio-fertiliser Panchagavya, but any excess finds its way to the store. Rare as it is, it sells for Rs. 2,000 per kilo.

Also read: Sasbani’s 'fruits' of labour: Reviving hope in rural Uttarakhand

Mangoes are the one exception to Ammachi’s model, sold primarily as fruits rather than fruit products. Here too, however, she maintains firm control over the supply chain. “I have not given any dealers access to the farm. They would spray Cultar (a plant growth regulator) on its foliage and apply some to the soil near the trunk. That is not acceptable to me,” she asserts. Instead, she packs and ships the fruit independently, earning loyal customers across the country. Any unclaimed mangoes are restyled into mango thoran (a dry vegetable dish) or mango peratt (a type of pickle). With over 300 mango trees of eight varieties spanning 10 acres, she earns Rs. 9 lakh from mango and mango-product sales alone.

Although customers can visit the farm premises, the majority of its sales are generated through its website. Ammachi's son, Sajith, who helped her clear the land when she first began farming, supported her in the building of the digital front of the store, along with his brother Sabith. Her daughter Sabitha handles the farm's social media and hosts visitors. Her youngest son, Ani, helps her with the physically demanding tasks on the farm.

Her independent storefront has seen such booming success that she has never had to sell her produce outside of the farm walls. As a result, she has never even had to avail of Kerala’s paddy procurement scheme, colloquially referred to as ‘Supplyco’. Rather, she earns a whopping Rs. 18 lakh of profit from paddy cultivation, after accounting for initial expenses amounting to Rs. 2 lakh. “Agriculture is not a loss-making venture,” she declares. The proof surrounds her.

{{quiz}}

You don’t need a garden or a fancy bin to begin composting—just a pot, a spot, and some patience.

Editor’s Note: In this series, the Good Food Movement explores composting—a climate-friendly, organic way to deal with waste. We answer questions about what you can compost, how to build composting bins and how this process can reshape our relationship with nature and our urban ecosystem.

The internet is teeming with backyard composting tutorials. The market offers a dizzying range of compost bins to choose from. If you find composting intimidating, you’re not the only one. But here’s a secret—composting is only as demanding as you make it.

Your compost bin can live on your terrace, or balcony, or windowsill, and thrive equally well everywhere. That said, your compost pile does need good air flow (to welcome the nice, oxygen-loving microbes which break down your food without producing methane as a by-product). Partially shaded corners of a balcony or a windowsill with minimal temperature fluctuations are ideal spots to house your compost.

Then comes the question of the compost bin: what kind should it be, and what size? Remember, composting is a process of learning. Getting your hands dirty makes you acutely aware of how much food waste you generate, and how it is broken down. It helps, in such cases, to start with a rudimentary bin. Grab a flower pot or bucket. Punch some holes at the bottom, and place it on a plate to collect any liquids that might seep through; the process is similar to growing a plant! Cover this with another lid or a plate, and there you have it: a starter-friendly compost bin.

Also read: Why composting is good for your garden—and the planet

Levelling up

As time passes, and you grow more comfortable with the process, you can choose to turn one bucket into two, or to invest in a larger container. Much like how a starter for sourdough bread (a live culture of yeast and bacteria) ‘feeds’ and enhances a new batch, your compost bin also needs a base layer from a fellow companion. Ideally, borrow some compost from a friend to fill up the bottom one inch. If you are the torchbearer of composting in your social circle with no one to borrow compost from, fret not – some shredded newspapers, coconut fibre and curd or buttermilk will work the same magic.

Also read: Don't dump it, compost it: Why peels and scraps shouldn't be tossed into your garden

Stirred, not shaken

Finally, you have a bin ready to receive your leftovers and kitchen scraps. But is your waste ready for the compost bin? Composting works best when your scraps are chopped into tiny pieces. This increases the surface area of the waste, and thus the speed at which microbes can nibble away. It is also a good practice to drain the vegetables of all water before tossing them into the compost bin.

Once chopped and drained, your kitchen waste is ready to enter the compost bin. Add in browns (like coconut husk or dry leaves) proportionately—roughly 3-4 times the greens (i.e. vegetable and fruit peels)—and cover the bin to prevent any pest troubles. Stir things up once a week and observe how the contents of the bin change. As the volume shrinks and the pile heats up, your compost will take on an earthy, pleasant smell. Take a moment to appreciate your hard work—your compost is on its way.

{{quiz}}

Please try another keyword to match the results