Pollution and urbanisation are putting an ingredient and livelihood at risk

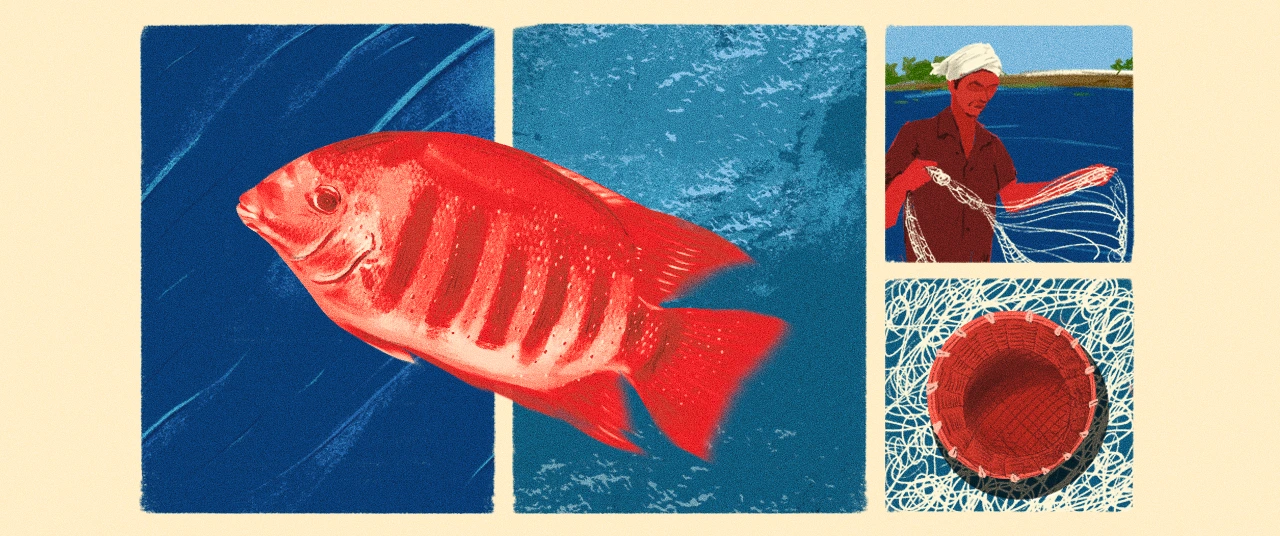

At the heart of the Kashmir Valley, where the still waters of the Dal Lake run deep, grows a humble yet special vegetable—the lotus stem. It is known as nadur or nadru/nadroo in the local tongue. The vegetable holds significance in Kashmiri traditions and cuisine—an ingredient that lends an earthy sweetness to everyday dishes, which is also treasured as a delicacy on special occasions.

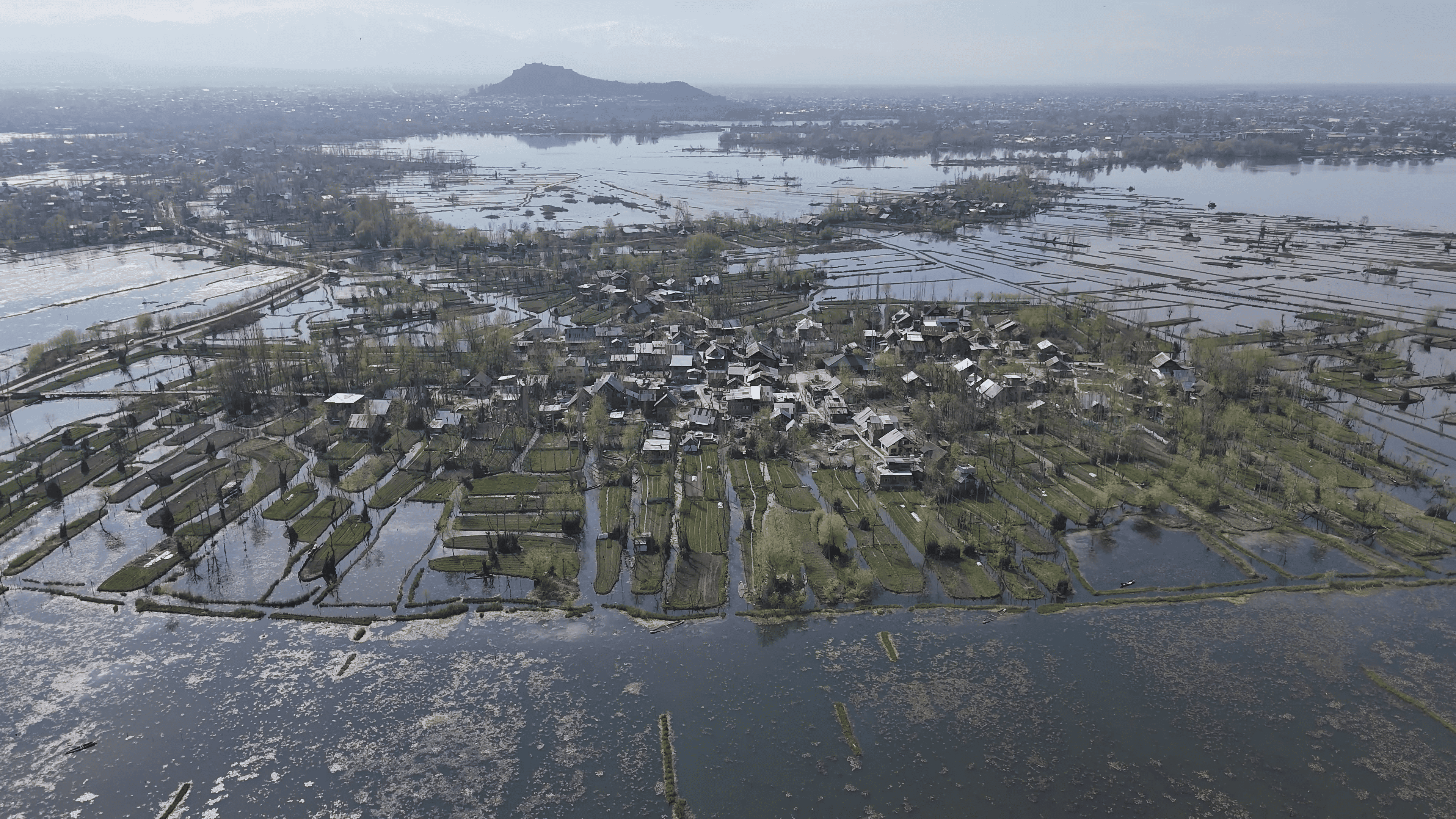

For generations, farmers and fisherfolk have harvested nadur from the Dal Lake, which is nestled between the mighty Zabarwan Range and the busy city of Srinagar.

Mohammad Abbas’s family has been harvesting the crop for over 60 years. The farmers step onto their narrow wooden boats and row out into the lake's interior. Wherever the soil is hard and compact, they dive into the waters to pluck the stems manually, emerging with bundles of long, delicate white stems. When the soil is loose, they use a tool known as kaeyshum (a long staff typically made of study woods like willow and deodar, with a slightly curved end, allowing fisherfolk to gently rake the riverbed) to extract the crop. “Not everybody can wield this tool,” says Abbas with a chuckle. “You need years of experience, patience and skill. My father and uncle taught me the intricacies of this trade, which I have now passed on to my children,” he adds.

%20(1).png)

Nadur has been a source of livelihood for thousands in Kashmir. Firdous Ahmad, who has been in the business for 12 years, says that the vegetable holds a place in his heart. “This is the king of all vegetables.” But increasingly, this way of life is under threat. The Dal Lake, which once spanned over 22 sq. km, has now shrunk to 18 sq. km, and struggles against an escalating environmental crisis.

The lake is the nucleus of Kashmir’s tourism, but the fragile ecosystem it houses is now in distress. Nearly 44 million litres of waste from Srinagar, including polluted water, untreated sewage, domestic and tourist waste, and human excreta, flow daily into the Dal’s waters, contaminating them. Additionally, nearly 50,000 people reside along the lake's banks. Tourist shikaras, agricultural and domestic practices around the lake, as well as encroachments have contributed to its deterioration. Srinagar’s rapid urbanisation has outpaced the capacity of existing sewage systems. Even Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) that have been installed to treat wastewater around the Dal lake often malfunction, exacerbating the crisis.

Levels of poisonous substances like nitrates, phosphates, lead, and arsenic have crossed thresholds of what is considered safe drinking water, also poisoning the lake’s aquatic life in the process. Fisherfolk and vegetable growers who depend on the lake to feed their families bear the brunt of the lake’s slow death.

Also read: The perilous future of Kashmir's once abundant trout

A dire need for change

Nadur farmers call for urgent action. The surrounding areas must be equipped with proper drainage systems, and nets must be installed at the end of rivulets to filter out waste, they say. The first lotuses bloom in April, and the stems mature by mid-September. After this, harvest commences and continues till the following April.

“Earlier, we could harvest around 550 bundles, or 750 kilos, from one kanal (kanal is a traditional unit of land measurement, roughly equivalent to one-eighth of an acre). Now, production has fallen by nearly 50%,” Abbas says.

Nearly Rs 23,900 lakh have been allotted to the restoration of the Dal in the last five years, Kashmir’s Home Ministry Affairs department says, but it is unclear how many of these funds have been utilised, pointing to administrative bottlenecks.

Akhtar Malik, a scientist at the Centre for Biodiversity and Taxonomy, Kashmir University, says that a bountiful harvest of nadur is an indicator of the lake's good health. Even previously, natural disasters have impacted the cultivation and harvest of these lotus stems. For instance, the floods of September 2014 disrupted the entire region around the Dal Lake, affecting marine life and vegetation, including the nadur. After more than two years, when there was still no sign of a new crop, distraught farmers plucked lotus seeds from a neighbouring lake and planted them in this region. About a year later, their efforts came to fruition when lotus stems started swaying underwater again.

Harvesting nadur is tough labour. At the break of dawn, nadur farmers dive into the frigid water—searching by touch in the murky depths. This underwater foraging requires not just skill and patience, but endurance—it is work done in biting cold, often from dawn till dusk, with harvesters spending entire days on boats without breaks.

What makes this labour even tougher today is the deteriorating quality of the lakes. Harvesters are now exposed to contaminated waters that pose serious health risks, including skin diseases, respiratory issues, and other long-term illnesses. Despite these dangers, the work continues—fewer stems, more risk, and dwindling rewards. What was once a steady, seasonal livelihood tied closely to tradition has become a test of resilience against both natural and man-made catastrophes.

Outside of the nadur season, farmers turn to vegetable fields, their hands tending to other roots. But come winter, they return to the waters, where for a day's labour under cold skies, they earn ₹1,000 and a bundle of lotus stems for themselves. Each bundle contains 15 to 16 slender, fibrous stalks, plucked with care and tied tight. Before the 2014 floods, farmers could harvest 40 to 50 bundles per day, but production has dropped significantly due to the contamination of lake waters.

Harvesters are now exposed to contaminated waters that pose serious health risks, including skin diseases, respiratory issues, and other long-term illnesses. Despite these dangers, the work continues—fewer stems, more risk, and dwindling rewards.

Also read: Why bajra, the 'pearl' of India's millets remains underutilised

Saving a traditional ingredient—and culture

Legend has it that nadur found its way into Kashmiri cuisine in the 15th century. Badshah Ghiyas-ud-Din Zain-ul-Abidin, the eighth sultan of Kashmir, was on a leisurely boat ride around the Gil Sar lake. He stopped to admire the lotuses, and his boatmen plucked their stems and added them to that evening’s supper on a whim. Today, nadur features in street food and is popularly cooked with fish, served to visitors, and consumed by families during celebrations.

The stems contain Vitamin-C and B-6, potassium, thiamine, copper, manganese and plenty of fibre, making it both a nutritious and flavourful ingredient. “Our elders say that the taste of the vegetable has changed over time, a testament to the deteriorating quality of the Dal Lake,” Afshan Rashid, a Kashmir-based food blogger says. “We also have to spend more time cleaning and peeling the stems as compared to before.”

{{marquee}}

Nadur may be disappearing from the waters of the Dal Lake, but all hope is not lost. Apart from Dal, the lotus stem also grows abundantly in several other wetlands and water bodies across the Kashmir Valley—including the Wular, Anchal, Manasbar and Haigam lakes and the Hokersar wetlands. A case study of the Wular Lake, a freshwater lake located approximately 40 kilometres from Srinagar, tells a similar story of nadur being consumed by contamination and rapid urbanisation, but then recovering and growing abundantly with the revival of the lake.

The stems contain Vitamin-C and B-6, potassium, thiamine, copper, manganese and plenty of fibre, making it both a nutritious and flavourful ingredient.

Also read: Protecting place and power, not people: The trouble with GI tags

The devastating 1992 floods of Kashmir deposited thick layers of silt across lakes in the Valley. Reports suggest that the Wular Conservation and Management Authority (WUCMA) has strategically dredged and desilted approximately 5 sq. km of the lake, especially in its Saderkoot basin. Altaf Hussain, Coordinator of Water Management at WUCMA says that desiltation was carried out between 2020 and 2023, after which authorities also sowed nadur seeds. “We are essentially restoring it to its original wetland condition,” Hussain says. Their efforts restored not just an ecosystem, but a community’s lifeline. Like a lost love returning, the pink lotuses and its stems are gracefully floating on the lake’s water again, after a nearly three-decade long absence.

This marks hope on the horizon. Similar conservation efforts for the Dal Lake, including managing the water's pH levels, preventing untreated sewage from threatening the river’s life, and a gentle revival effort can ensure that nadur blossoms in its waters again. Urgent and focused action can mean the difference between life and death for Kashmir’s culinary and ecological legacy.

Images by Muneem Farooq Itoo and Suhail Ahmad

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

Which traditional tool is used to harvest nadur?

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)