Minal Sancheti

|

December 16, 2025

|

6

min read

Mumbai’s mill-era ‘khanavals’ fuelled a workforce with affordable, homely meals

Timed to mill shifts and featuring generous proportions, these meals signified sustenance and community

Read More

A growing demand for nutraceuticals is threatening fish populations and marine food webs

The oceans appear vast and resilient, stretching in endless blue horizons and rich with life. Yet, beneath the surface, a more urgent reality is unfolding. Even as the planet warms and marine ecosystems struggle to keep pace, extraction of resources driven by human demand reaches beyond just seafood–environmental costs of which are slowly, but steadily, rising. The World Bank estimates that nearly 90% of the world’s fish stocks are under stress now, either overfished or close to it.

The global appetite for dietary supplements is rapidly growing. The omega-3 fatty acids market, for one–valued at $2.62 billion in 2023–is projected to reach $4.45 billion by 2030. The demand for omega-3 is projected to increase even more with rising awareness about its health benefits. Consequently, this means that extraction pressures will grow in tandem with demand, as the industry prepares to capitalise on this.

Omega-3 fatty acids are polyunsaturated fats that are extremely important to the human body and health: they help our body grow healthy cell membranes, which further ensures many benefits to our heart, brain, metabolism, and immune system. Research even suggests that omega-3 can help manage cholesterol; they also help lower triglycerides in the body, which are fats that, at high levels, increase the risk of heart disease and stroke. There are three types of omega-3s, of which EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) are especially valued. But unlike many other sources of nutrition required to keep the human machine humming, omega-3 is actually not produced inside the body.

And so, they are called "essential fats”: you need to consume them in some form externally, like from your diet or as supplements. Omega-3 are “good fats” that you can get from your diet if you consume oily fish, other seafoods like oysters and shellfish, seaweed, chia seeds, flaxseeds and walnuts; as supplements, omega-3 is available as fish oil, krill oil, algal oil and flaxseed oil pills.

Also read: The promises -- and perils -- of aquaculture

Omega-3 fatty acids are typically sourced from fatty or ‘oily’ fish such as mackerel, cod, salmon, herring, tuna, and sardines, as well as walnuts, soybean, and flaxseed. Fish continue to be the primary source for omega-3 supplements due to a higher EPA and DHA content–that is, the omega-3 obtained from fish have these two, long-chain fatty acids that prove to be beneficial to health. Fish oil was the only widely-used source until the 2000s, when microalgae-derived omega-3 was officially approved for use in supplements by the FDA (as a GRAS notification, or what is called ‘Generally Recognised as Safe’).

Omega-3 is sold in bottles across the world, often labelled as “3x strength” or “wild fish oil”. While the labels offer an attractive–and to a certain extent, valid–appeal, they fail to represent the bigger picture of this industry, and the processes involved in holding it up. Fish-based oil has always been a major component of the omega-3 supplement industry, followed by algal oil, krill oil, and other plant-based sources. While fishing pressure, concern over declining fish stocks, and a demand for vegetarian and vegan options may have pushed for non-fish sources, as of 2023, 83.5% of the total revenue brought in by the omega-3 industry still came in from marine sources, like fish and krill, and in small parts, microalgae.

While the labels offer an attractive–and to a certain extent, valid–appeal, they fail to represent the bigger picture of this industry, and the processes involved in holding it up.

However, while fish oil is the most common source of omega-3, it may not be the best. Fish oil can often be contaminated with heavy metals, pesticides, and other toxic compounds, which are usually fat-soluble; the contaminants dissolve and remain in the oils that are later extracted from fish. Anthropogenic activities–that include industrial and agricultural runoff into the ocean–have introduced these harmful pollutants into the marine ecosystem; they are quickly absorbed and assimilated by fish over time.

In 2008, another source was officially approved for omega-3 fatty acids—the Antarctic krill, which are tiny crustaceans that form the foundation of the Southern Ocean food web. Penguins, whales, seals, and seabirds rely on krill, which are currently being extracted at alarming rates for the fisheries as well as nutraceutical industries.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), responsible for fisheries management and conservation of the marine ecosystem in the Antarctic, had proposed a management framework. But this framework, which prevented the overharvesting of krill and placed scientifically-backed fishing limits in several areas, expired in 2024, mainly because the CCAMLR could not, in time, finalise a revised management plan before the expiration date. With no consensus on a new framework in sight, catches of Antarctic krill are expected to increase beyond what the ecosystem can sustain, at a rate faster than the krill populations could realistically recover at.

The spawning and reproduction of Antarctic krill are dependent on the climate, seasonal sea ice conditions, and oceanic currents, all of which are now affected by climate change, further impacting their numbers. The Antarctic krill fishery is the largest fishery by weight in the Southern Ocean, and most of the fishery extracts are concentrated in regions where marine animals are known to feed on them–essentially depleting natural feeding grounds.

Also read: The perilous future of Kashmir's once-abundant trout

Interestingly, humans are not the only ones relying on fish and krill. Krill fisheries not only cater to the omega-3 supplement industry, but also aquaculture and unusually, the pet cat and dog food industry. Nutrients extracted from krill, including omega-3 fatty acids, proteins and antioxidants are key constituents of pet food. Similarly, large-scale aquaculture relies heavily on fish feed and oil, extracting large amounts of the natural food from the oceans to channel into aquaculture.

Krill fisheries not only cater to the omega-3 supplement industry, but also aquaculture and unusually, the pet cat and dog food industry.

Some of the fish commonly sought for omega-3 fatty acids—sardines, anchovies, herring, and mackerel—are also ‘forage fish’. These are small to medium sized, highly productive pelagic (open ocean) fish, and along with krill, they form a critical and large resource that most marine animals subsist on in food webs. Krill and forage fish are crucial prey for several other larger fish species; they are considered a ‘keystone species’ for their important role in the food chain. Removing them at industrial scales is not just reducing biomass, it is reshaping entire ecosystems.

Forage fish are attractive for fishers seeking short-term commercial gains due to their aggregating nature which makes them easy to catch. They make up around 30% of the global fish catch, a large proportion of which is now being used in aquaculture. Antarctic krill too, are relatively low-effort catch due to the large aggregations they are found in. In 2024, the Antarctic krill fishery closed early after record catches sparked concerns about overharvest and the impacts on the wildlife that subsists on krill.

Asia-Pacific is projected to be the fastest growing market for omega-3 supplements, with highly populated, fast-growing economies like India and China leading the way. While fisheries are fairly regulated globally, there is limited or poor enforcement in some pockets, which could be a cause for concern in the long term.

All of this extraction is happening against the backdrop of climate change, which is already straining the ecosystem. Overfishing and the resultant loss of biodiversity can make oceans less resilient to the vagaries of climate change. Precautionary approaches, ecosystem-based management, and international cooperation with mutually-agreed caps to keep extraction within sustainable limits might work, but it remains to be seen.

Also read: The intertwined fate of Navi Mumbai's Kolis and the Kasardi river

Omega-3 is important, and it makes up nearly 25% of the total fatty acids found in the brain’s grey matter. So, if not krill- or fish-derived oil, what is the alternative?

The good news is that alternatives are emerging, and some have existed for a while. Algal oil, derived from marine microalgae, can replace fish- and krill-derived omega-3s, delivering the same EPA and DHA without impacting marine food webs. These microalgae are phytoplankton—tiny, microscopic plants that fish feed on—and the source of fatty acids for fish. Marine algae-based extraction will reduce dependence on fish and krill, offering a more sustainable source for an important supplement. Algal oil has also been found to be cleaner, richer, and devoid of the odour and heavy metal contaminants often found in fish oil.

While marine microalgae-based omega-3 fatty acid supplements are unlikely to replace fish- and krill-derived oil completely, the data does indicate a shifting trend that could restore some balance.

While there are several logistical constraints that prevent industries from scaling up algae production and algal oil extraction, there exist innovative techniques that ensure high-quality extraction without the worrying environmental impact. The algal oil-based omega-3 market is undergoing a shift, and ‘sustainability’, ‘plant-based’, and ‘traceability’ are the buzzwords driving this revolution. Valued currently at $1.6 billion, it is projected to grow to $2.68 billion by 2030, pushed by consumer preference for alternatives.

While marine microalgae-based omega-3 fatty acid supplements are unlikely to replace fish- and krill-derived oil completely, the data does indicate a shifting trend that could restore some balance. Furthermore, emerging research shows that even some macroalgae or seaweeds can offer similar omega-3 benefits, albeit on a smaller scale. Improved innovation, increased consumer awareness, and consumers making informed choices, could well change the dietary supplement landscape in the years to come.

{{quiz}}

Being mindful of the presence of wild animals can help conserve agrobiodiversity and reduce crop loss

Editor’s note: To know Rama Ranee is to learn about the power of regenerative practices. The yoga therapist, author and biodynamic farmer spent three decades restoring land in Karnataka, envisioning it as a forest farm in harmony with nature. In ‘The Anemane Dispatch’, a monthly column, she shares tales from the fields, reflections on the realities of farming in an unusual terrain, and stories about local ecology gathered through observation, bird watching—and being.

On a boulder to the north of the Bannerghatta National Park, facing the Suvarnamukhi Hills, lies the Anemane Farm. A tarred road, once an old dirt track, snakes down from our village Kasaraguppe to the national park 4 km away, and Bengaluru city thence. Bamboo thickets cover much of the hill sides. Taloora Lac trees (Shorea roxburgii, or ‘Jalari’ in Kannada) rear their evergreen crowns among bare rocks.

The farm shares the national park’s topography and natural vegetation; the average elevation is about 900 m, the GPS coordinates being latitude = 12°48'45.85" N, and longitude = 77°34'02.73". Among India’s largest scrub forests, Bannerghatta serves as a vital link between the Eastern and Western Ghats, and is critical for the conservation of many threatened large mammals. The assigning of national park status has facilitated the restoration of green cover, and consequently, a resurgence of wildlife since the 1970s.

Significantly, it is one of the oldest habitats for the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).

We are privileged to share this unique landscape with elephants and other wildlife. However, their impact on land use and farmers’ livelihoods is immense. Over the years, a benign acceptance of elephant presence near human habitations has changed potentially into conflict, chiefly due to damage to crops and threat to human lives.

Significantly, it is one of the oldest habitats for the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).

The causes are complex, and beyond the likes of us to discern. As farmers, our concerns are immediate and practical: it is difficult to predict what the next herd or individual may or may not do or eat. Every season is an experiment and an adventure. It has taken 30 years and a fair measure of resources to arrive at a list of ‘safe-crops’ and some realistic expectations.

This is how a typical morning at Anemane unfolds: The mist lifts, unveiling fields of citrus. I wait for the sun’s rays to reveal paths, not wanting to step into the unknown. Elephants are amorphous, melting into the vegetation. There are a couple of young tree branches on the ground and heaps of ripe figs on fresh elephant dung. The old Cluster Fig tree has withstood such elephant forays and is none the worse for it. As for the rest of the farm, it has undergone waves of transformation with emerging patterns of elephant activities and behaviour.

Like other communities at the forest’s edge, Kasaraguppe, too, has its share of encounters with these animals and continues to grapple with them. I wondered how farmers in the past managed to put down their roots, raise crops and families. An old-timer whose services we fortunately enjoy opened a window to those bygone times: Rajappa’s was one among eight families which migrated from Tamil Nadu in the late 1950s, in search of greener pastures. The land, as it turned out, was a hilly wilderness. Bamboo thickets were cleared and terraces wrought from slopes for fields of ragi, groundnut, flowers and paddy in the valleys. There were grasslands for livestock on the hills. As time turned under the yeoman’s plough, there was contentment—though leopards posed a threat to domestic animals, and wild pigs restricted their choice of crops.

Also read: At Ammachi’s farm, the impossible can be achieved—and made profitable

In 1971, the Bannerghatta National Park was inaugurated. This event was associated with the arrival of elephants to Kasaraguppe by the farmers. Initially, it was a rare occurrence; an occasional herd would pass through, peacefully. Once Chikka Bodappa, one of Rajappa’s fellow villagers, planted ragi with great care. That year, an elephant strayed into his field and tasted a small clump of the millet. Bodappa’s yield was ten times above the normal amount, which he attributed to the blessings of the visitor. Its pad mark was worshipped with reverence, and the villagers treated to a festive lunch. This set the trend for other farmers who began to invoke the blessings of the ‘sacred’ elephant in the hope of bountiful harvests. Rajappa ruefully admitted that there was not a single household that escaped the magical spell of the myth—and Chikka Bodappa’s good farming methods were disregarded in the process.

As the pad imprints in fields multiplied, the farmers despaired and sought respite from elephants.

As the pad imprints in fields multiplied, the farmers despaired and sought respite from elephants. The ragi and paddy seasons required utmost vigil, and the families banded together, braving rain and shine to fend the animals off, sleeping in the fields for days. There was a growing urge to give up farming. Such was the scenario when we began to farm.

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

The ten-acre land in our possession was degraded: bald rocks dotted an undulating terrain, pockmarked with shallow granite quarries. Fallow fields baked under the sun, bleached from generous inputs of chemical fertiliser with a sprinkling of granite dust. The soil was shallow and varied in depth, susceptible to erosion. The Cluster Fig in the valley was a lone sentinel over an elder’s grave. Rain brought to life streams; a swift little one gurgled along the edge of our land, and muddy cascades turned the valley into a marsh, often washing the fields away.

Restoring soil fertility became our primary goal. Defunct quarries turned into ponds to harvest runoff from the hill. Seedlings of local varieties such as the Pongam tree (Pongamia glabra, or ‘Honge mara’ in Kannada) were raised and planted along the periphery to arrest erosion and build up organic matter. Teak and silver oak in the interspaces of fields served as wind breaks. The edges bordering the forest were left alone for native species to revive.

Efforts at regenerating the land were rewarding, but with them came unforeseen consequences: our ponds served as watering holes, and the wooded valley— sheltered by bamboo and the wilderness bordering the forest—was virtually an elephant ‘camp’.

Manure infused life into the depleted soil, sustaining guava, papaya, lemons, and pomegranates, while contributing a new crop of trees, Maha-neem (Melia dubia, or ‘Kaadu Bevu’ in Kannada). The papayas were a sweet success but only briefly; the first time an elephant herd stomped into the fields, all the papaya stems were snapped. None were eaten. After the occurrence of similar episodes, we realised that elephants destroy fine stemmed trees like Moringa and Hummingbird (Sesbania grandiflora, or ‘Agase Mara’ in Kannada).

Efforts at regenerating the land were rewarding, but with them came unforeseen consequences: our ponds served as watering holes, and the wooded valley— sheltered by bamboo and the wilderness bordering the forest—was virtually an elephant ‘camp’.

The saga of a fruit farmer’s unfulfilled dreams further unfolded with a special variety of banana, Nanjangud rasabale. They never saw the light of the day! An elephant in a banana field is like a kid in a candy store. It was of little consequence that the entire village had gathered to chase them away.

Coconut palms met a similar fate. The first flush of flowers caught the elephants’ superior olfactory sense. It was a carnage: within a year, a hundred palms were mere shells left to wither away. When Ratnagiri alphonso mangoes began to fruit, every elephant that passed by helped itself to not just the fruits, but also the branches—possibly to rub itchy backs or merely on a whim. Along with the mangoes went guavas and sapotas, too. After 20 years of trying to revive the stunted, damaged trees, we finally cut them down to prevent further raids.

An elephant’s playfulness is further incited by water bodies and slush. Our paddy field has been akin to a playground. One utterly dark, rainy night, the silence was shattered by deep groans and roars; the earth trembled beneath our feet, literally. The next morning, we saw that the erstwhile paddy field had turned into pools of sludge and mush. The banks had all but disappeared. The only evidence of the night’s revelry attributable to elephants was the scoured floor and imprints of bodies.

Elephants are vigorous post-monsoon, when paddy and ragi ripen. With some luck and nightly vigils, many households managed a harvest, prompting us to sow seeds for several years. Our hopes were raised periodically by the forest department’s assurances of elephant-proofing with solar fencing, trenches, and massive rubble walls. At best, these offered a short reprieve.

Once the other farmers gave up, it became difficult to sustain these crops. Our final attempt was a small patch of paddy grown according to the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) which would have led to a bountiful yield had a lone elephant bypassed the field. We retrieved some of the stalks and piled them up in a rick for the cows. A few days later, the rick was a messy heap—the paddy straw pulled out and consumed, while the sorghum was left uneaten. The lone elephant had discovered the way from the paddy field via the lemons to the rick; not much of a distance, but until then, it was an untrodden path.

Paddy, ragi and fruit farming seemed fraught with risks, so we directed our efforts to millets, legumes, vegetables, flowers, and varieties of citrus. For four blissful years, the fields hummed with bees. Gourds, tomatoes, cucumbers, ladies’ fingers, marigolds, and chrysanthemums thrived, until an elephant acquired a taste for sorghum and avarekai (hyacinth beans), and seemingly memorised our planting calendar as well. Winter and early summer vegetables, crucifers, gourds and tomatoes were sought after. There were many styles of operation, not necessarily a rampage. To explore the contents of a covered patch, a particular tusker punctured the net neatly and then barged in to feast on cabbages.

Also read: No monkeying around on this kiwi farm

Our options have been whittled down to citrus, spices, aromatic herbs, medicinal plants and flowers. Yet, the success of ashwagandha, with immense healing properties and importance in Ayurveda, was short-lived. Just as they were fruiting, the plants were neatly uprooted, and mature roots—the most valued part—eaten.

Nutritional needs otherwise accessible in a natural environment are supplemented through successful forays into farms. Elephants mark territories for specific crops and establish pathways though farmland and forest.

Variations in foraging behaviour—dietary preferences, if one may call them that; the number of individuals; the composition of the herd in terms of age and gender, from stealthy, lone night raiders at touching distance, to a club of boisterous young bulls are all factors which determine the extent of damage. Recently, we were the target of three young bulls who met at the edge of our farm and branched out towards preferred dining. One of them had a penchant for our tamarinds. Such behaviour is not only risky, but I expect, problematic, too, with associated health risks, as it disrupts the elephants’ normal habits of foraging in the wilderness.

Elephants are a part of the agricultural landscape on forest edges, enriching the soil with their dung, eliminating certain plants, while introducing some through seed dispersal, thus contributing to the diversity.

Three decades of appraisal has yielded the finalists which have stood the test of time and might even fulfill their life cycle. Among the cultivated plants, citruses are the front runners. Native trees such as Maha-neem, Taloora Lac, and Flame of the Forest (Butea monosperma), varieties of Terminalia (such as Arjuna, Crocodile Bark Tree, Black Myrobalan and Belleric Myrobalan), bamboo, shrubs including wild edibles, have flourished unbridled and untouched by elephant activity, turning the land into a green haven.

If farming is all about market success, then we are utter failures. The choices we made, some by intent and a few out of ignorance, have determined the outcomes. The prism of success, in economic terms, offers a narrow perspective. In the real sense, regenerative farming ensures long term food security. It contributes towards support systems that enable life. Restoration of soil fertility and conservation of agrobiodiversity through ecologically sensitive farming, integrating holistic practices, have been our chief concern. In that respect we have evolved, if the diversity of birdlife—more than 145 species in an area of 0.05 sq km—is any indication.

Elephants are a part of the agricultural landscape on forest edges, enriching the soil with their dung, eliminating certain plants, while introducing some through seed dispersal, thus contributing to the diversity. For instance, Wild Guava (Careya arborea, or ‘Goujal Mara’ in Kannada), a favoured elephant food that is disbursed by them, is well known to local folk health traditions. Recent studies explore its medicinal potential.

Being mindful of elephant presence and foraging behaviour can help farmers make better choices in terms of crops and planting cycles, thereby reducing losses while conserving agrobiodiversity—the key to sustainability. We are witnessing an increasing fragmentation of wild spaces and forests. Sharing a border with a forest makes us even more aware of our role as a stepping stone and a habitat for a host of organisms, big and small. A forest farm committed to ecologically sensitive farming can serve a vital function.

{{quiz}}

Artwork by Khyati K

Most of our waste ends up in landfills, which pose risks to public health and the climate

Editor's Note: In this series, the Good Food Movement explores composting—a climate-friendly, organic way to deal with waste. We answer questions about what you can compost, how to build composting bins and how this process can reshape our relationship with nature and our urban ecosystem.

If you’ve ever walked past a roadside garbage dump, you are familiar with the exact odour that overwhelms your sense of smell: a blend of rotten eggs, urine, and metal. You may scrunch up your face, pinch your nose, and hurry past on tiptoe, but it will be to no avail. The smell spares no one.

If a small roadside garbage dump creates such an effect, a designated landfill is only worse. The smell is potent enough to sting your eyes, soak through your clothes, and stick to your skin long after you leave it behind. And what you can’t smell, seeps into your veins: methane and carbon dioxide – odourless gases notorious for their role as greenhouse gases, which also restrict the body’s access to oxygen.

For many of us, walking away from the horridness of a landfill is easy. But thousands of people are subjected to this biohazard everyday—they collect, transport and manually scavenge this waste with little to no protection. As long as waste is indiscriminately generated in urban India, landfills will continue to pile up, and manual scavenging—which has deep roots in caste—will continue to be a reality.

Most international guidelines require at least a 500 m buffer zone around all landfills, and the Karnataka state government goes so far as to require a 1 km buffer zone around all landfills. By the government’s own admission, most buffer zones are encroached given the scale of overpopulation in most cities.

Every day, the Bengaluru Urban district generates 4593 tonnes of waste, of which 2399 tonnes (52%) is food waste. In reality, the amount of food waste is likely higher—these figures indicate the separated wet waste that made it to urban collection centres. The municipal corporation operates separate dry and wet waste processing centres. In certain areas, waste is composted or recycled before sending unreusable waste to landfills—for instance, out of the separated 2399 tonnes of food waste, only about 55% (1328 tonnes) gets converted to compost. At other centres, all waste is sent directly to landfills without processing.

Most gases in landfills come from anaerobic decomposition of organic matter—and over 45-60% of landfill gas is made up of the greenhouse gases mentioned earlier: carbon dioxide and methane. Though chemical waste like discarded metal, cosmetics and toiletries can still create toxic compounds like benzene, reducing organic waste in landfills is a sure shot way of reducing not only greenhouse gas emissions, but also the production of foul-smelling gases like hydrogen sulphide.

Bengaluru’s city municipal corporation, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) has earmarked Rs. 1,400 crore for Bengaluru Solid Waste Management Limited (BSWML) for 2025-26. Of this 1,400 crores, it expects Rs. 750 crore to come from a newly implemented user fee for waste collection. This user fee has invited skepticism from both the public and the media, who disparagingly refer to it as 'garbage tax.' It ranges from Rs. 10 to Rs. 400 per month, and has been incorporated as a component of property tax since April 2025. BSWML currently spends around 590 crores per year on the collection and transportation of municipal solid waste. In a tender dated June 2025, it estimated the costs of secondary collection and transportation (i.e. transporting waste from processing centres to landfills) to be Rs 1,590 crore.

Let's be clear: this money is being used to drive our waste about 40 km every day—using fuel and blocking traffic only to end up in a landfill. Waste put in landfills does not go anywhere; rather, it becomes our heritage. Aptly called 'legacy waste', its informally agreed upon definition is waste that has languished in a landfill for more than a year. Formally, it remains undefined by any Indian authority.

Generally, urban local bodies are recommended to employ biomethanation when they are processing more than 50 tonnes per day (TPD) since it is only cost effective at scale. At a small scale, composting is championed because of minimal technology and investment requirements.

Not only does the waste in landfills take up valuable space, it damages the surrounding environment. It produces leachate, which is a contaminant formed when water flows through the waste, and results in groundwater contamination. Though modern landfills are lined with impervious materials like (ironically) plastic, some amount of seepage or leakage is inevitable in any landfill over a period of time.

As a Karnataka High Court judgement aptly states: 'Landfills are only temporary solutions and long term measures have to be initiated by all concerned authorities as a permanent solution.'

Landfills are also a health hazard to everyone living in their vicinity. In addition to damaging respiratory health, they also contaminate groundwater, crops, and even milk. Most international guidelines require at least a 500 m buffer zone around all landfills, and the Karnataka state government goes so far as to require a 1 km buffer zone around all landfills. By the government’s own admission, most buffer zones are encroached given the scale of overpopulation in most cities.

Also read: The circular bioeconomy movement can change how we see waste

If landfills are not a permanent solution, what is? In the Indian context, an effective approach that stands out is the circular economy. A circular economy is a system where instead of completing a linear life cycle and ending up as waste, materials keep getting circulated through processes like maintenance, recycling, or refurbishment. The subset of this philosophy that applies to bio-resources is called circular bio-economy, and deals with repurposing bio-materials.

Two fundamental pillars of the circular bio-economy are composting and biomethanation (the process of converting organic matter to biogas). Generally, urban local bodies are recommended to employ biomethanation when they are processing more than 50 tonnes per day (TPD) since it is only cost effective at scale. At a small scale, composting is championed because of minimal technology and investment requirements.

Eighty percent of Alappuzha households now have either biogas plants or pipe composting systems; the rest have their waste collected and sent to a municipal composting unit.

Currently, most of India's local bodies process some portion of their wet waste into compost or biogas, either outsourced or through municipal composters and biogas plants. Collectively the waste processed amounts to roughly 49.5% of the total wet waste collected nationally. But these figures vary widely internally across municipal bodies, and still involve transportation costs to municipal composting centres.

It is far more efficient to decentralise the process and set up small local composting units in individual houses or housing societies. The compost it yields can be used by resident gardeners and green spaces within housing societies. Excess compost can be sold to farmers or even nearby nurseries and serve as an additional source of income.

Also read: Don't dump it, compost it: Why peels and scraps shouldn't be tossed into your garden

However, this doesn’t mean that the onus of responsible waste management should shift from the state to the individual. Individual efforts can lay the bricks of change, but administrative support must bolster it. Some Indian cities have made phenomenal changes to their waste management system. The most notable of them is Alappuzha, Kerala, which was recognised by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) as one of the world’s five most pioneering cities with respect to solid waste management.

The story of Alappuzha's transformation started with the people living next to the landfill refusing to allow waste disposal in their neighbourhood. After multiple failed negotiations, the municipality came up with a fresh framework for segregation and disposal. Eighty percent of Alappuzha households now have either biogas plants or pipe composting systems; the rest have their waste collected and sent to a municipal composting unit.

Similarly, the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS) launched a City-Farmer Partnership for Solid Waste Management in Chickballapur in Karnataka. Under this initiative, wet waste is collected from the municipal council, transferred to compost pits at farmlands, turned into compost, and given to farmers for free. Within just 6 months, over 109 farmers received 759 tonnes of compost.

Composting dominates conversations around soil rejuvenation, and rightfully so. But it has a paired benefit: reducing the strain on our solid waste management system. The circular bioeconomy flourishes when backed by administrative bodies that are deeply invested in equitable and sustainable civic care for its citizens. We must urge our governments to mobilise around the circular economy. And while we wait for policy to take shape, we must take ownership of the waste we generate. Composting is one of the simplest and most accessible ways to get our hands dirty, and change the fate of what would go into landfills to create something that fuels the land instead.

Also read: Trouble in your compost bin? Here are solutions for stink, slush and surprise guests

{{quiz}}

Smelly, potent, and packed with nutrients—chicken poop fuels farms.

Chickens—we know them, we love them, and probably have been chased by one down a lane at least once in our lives. They peck, they cluck, they run around like tiny, feathery dinosaurs who popped right out of Cher’s closet. And…they poop, a lot, like once in every 20-30 minutes.

The average chicken produces approximately one cubic foot of manure every six months, which is equivalent to almost 30 litres of manure—a small suitcase full of poop. And some people have dozens of chickens, so imagine waking up every morning, opening your back door, and being greeted by a mountain of freshly made, steaming-hot (potential) fertiliser.

Chicken manure stands out because it delivers a balanced nutritional profile. Unlike other fertilisers that comprise the primary trio of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, chicken manure naturally contains a larger number of essential nutrients that plants require for optimal growth, including critical micronutrients like calcium, magnesium, sulfur, iron, manganese, zinc, copper, and boron, that are often overlooked but vital for plant health.

Chicken poop is rich in nutrients because chickens eat a mixed diet, and their bodies pack those nutrients into a form that plants can easily use. The organic matter in chicken manure also improves soil structure and water retention while feeding beneficial microorganisms, creating a living soil ecosystem rather than just delivering a quick nutrient fix.

In Bhopal, a (2004) study found that combining 75% NPK (a fertiliser labelling convention pointing to the presence of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) with poultry manure produced better yields than with farmyard manure, a variant made of manure from various farm animals like cows and sheep, mixed with bedding materials like straw, especially for sorghum.

For a farmer, chicken poop is gold. However, one can’t just go around spraying and dumping raw manure onto their plants. It is something like a nuclear reactor; if not handled properly, it’ll straight-up burn everything in sight because of the nitrogen and ammonia present in it. Imagine what your body might go through if one evening you decided to replace your nerve-calming, 100% caffeine-free chamomile tea with a dozen shots of espresso.

That’s why the droppings need to first be composted for them to break down and mellow out. The process is also necessary to eliminate all the nasty little pathogens that could ruin the crops. If done right, what was once a pile of steaming horror turns into plant food. Farmers must also be mindful of which crops they use the manure on. For example, root crops that have direct contact with the soil—such as potatoes, carrots and beets—are a no-no because of the risk posed by pathogens within the manure. They can remain in the soil for weeks and possibly contaminate crops.

Composting chicken poop comes with its challenges. First, the overpowering smell of filth. If you’ve ever had the pleasure of being downwind of a fresh pile of chicken manure, you know what we mean. A poorly managed pile of chicken poop smells like someone bottled all the obnoxious odours under the sun and then shook it up for fun. That’s why experts suggest you keep the pile well-aerated, because nothing ruins neighbourly relations faster than an unexpected wave of Eau de Chicken Butt drifting across the kitchen window.

There’s also the pathogen problem. Raw chicken poop can carry notorious bacteria like the infamous E. coli, Salmonella, and a bunch of other microscopic nightmares. Being careful while handling it is crucial. So, wear gloves, wash your hands, and let the droppings cure for 45-60 days before. Also, add carbon-based materials like leaves, straw, wood shavings, or wood chips to balance the nitrogen in the manure and dial down the odour.

If you don’t have access to fresh chicken poop or don’t have the time to process it yourself, worry not, because that concern has already been taken care of by the agricultural experts. One can actually buy dried, pelletised chicken manure in bags across the internet.

Also read: Meet the minds investigating bugs lurking in poultry

Farmers have been using chicken manure for centuries. There’s even archaeological evidence that the first domestic chickens appeared around the time humans began cultivating rice and millets. Basically, ancient humans saw jungle fowls hanging around their crops and thought, “Let’s invite them over.” Ever since, the little feathered freeloaders continue to repay the favour the only way they know how—by pooping.

In Tamil Nadu, particularly in Namakkal and Erode, poultry manure is widely used in millet cultivation. Farmers also sell this manure to neighbouring states, where it is applied to vegetable farms, rubber plantations, and coconut orchards. A study involving 62 poultry farmers in Assam and Karnataka found that nearly 90% of them reused poultry waste as manure on nearby fields. In Nagaland, backyard poultry manure is incorporated into organic farming on a small scale, either through composting or direct application by smallholder farmers, with no involvement from large commercial operations. Additionally, research conducted at the Agricultural Research Farm at Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi demonstrated that poultry manure used in maize cropping systems led to improved yields and enhanced nutrient uptake.

Chicken manure stands out because it delivers a balanced nutritional profile.

In Bhopal, a (2004) study found that combining 75% NPK (a fertiliser labelling convention pointing to the presence of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) with poultry manure produced better yields than with farmyard manure, a variant made of manure from various farm animals like cows and sheep, mixed with bedding materials like straw, especially for sorghum. In Pune, baby corn trials (in 2009) showed that poultry manure led to the highest nutrient uptake and cob yield.

Globally, chicken manure has shown superior performance. A forage crop study found poultry manure boosted fresh yield by 145% and had roughly three times the nutrient content of cow manure. Very recently, in New Zealand, 20-25% higher yields were reported for maize and other crops, compared to cow, sheep, and pig manure. While cow manure improves soil structure, poultry manure offers more concentrated nutrients.

India currently does not provide direct subsidies exclusively for chicken manure. However, several states, like Goa, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Tamil Nadu and Nagaland, financially support poultry farm establishment (which produces manure).

If you have chickens and are planning to use the manure, you’ll also have an endless stream of chicken poop mysteries to solve. A lot about a chicken's health is revealed just by looking at its droppings. Too watery? Excess protein. Green and foamy? Possibly a disease. The moment you start raising chickens, you become a professional poop detective on the coop scene.

Whether you’re a farmer, a gardener, or just someone who loves a good omelette, somewhere, a chicken and its poop are working overtime behind the scenes, making sure we all stay fed.

Also read: Black Soldier Fly: A hero of insect farming and waste management

{{quiz}}

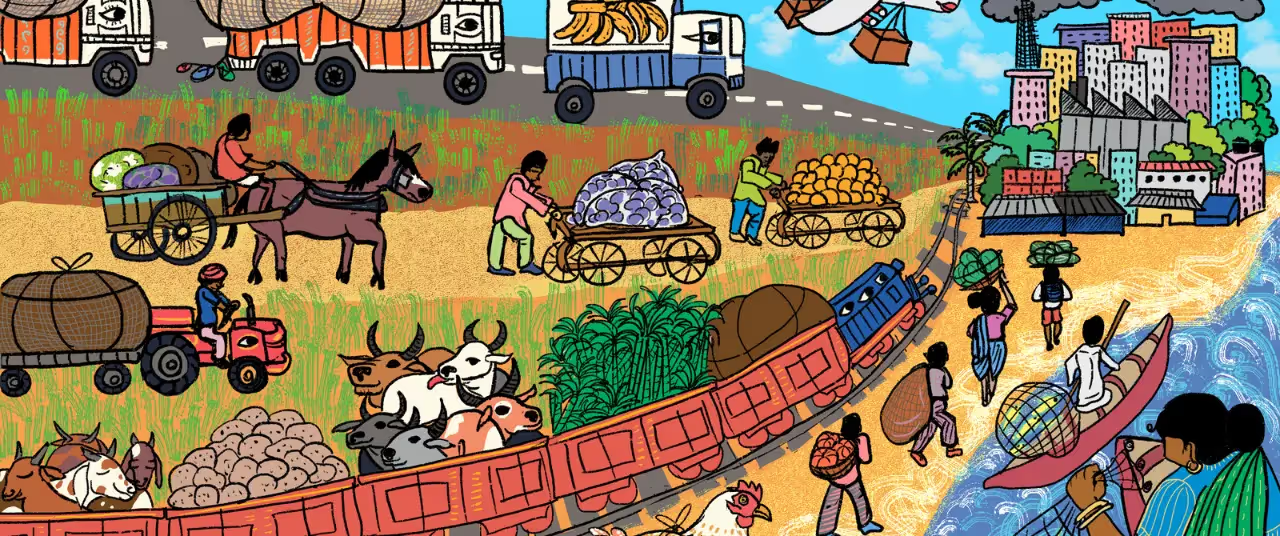

Behind well-fed metropolises are street vendors, produce that travels many kilometres, and fragmented supply chains

The Plate and the Planet is a monthly column by Dr. Madhura Rao, a food systems researcher and science communicator, exploring the connection between the food on our plates and the future of our planet.

Every morning, as India’s cities slowly come to life, crates of vegetables and fruits—some harvested just hours earlier in fields nearby—are unloaded in wholesale as well as Agricultural Produce Market Committee APMC (APMC) markets. Street vendors ready their carts for the day’s trade, small eateries fire up their stoves to serve the first wave of officegoers, and shelves at local grocery stores and supermarkets are stocked in preparation for the day ahead. Day after day, this quiet choreography sustains the vast and often invisible system that keeps cities fed.

But as India’s metropolises expand, these well-rehearsed routines are being reshaped. In this column, I take a closer look at what it means to feed a city fairly and sustainably in such a changing landscape.

Across the country, food reaches urban centres through networks that span vast and varied geographies. These supply chains link remote farms, peri-urban fields, fisheries, livestock holdings, and processing units to urban markets, grocers, eateries, and homes. Food in India travels shorter distances on average, compared to large industrial countries like the US. Food reaching American cities travels over 1,600 km per metric tonne; at around 480 km per metric tonne, food supply to Indian cities averages less than a third of that, owing to more regionally embedded production systems.

Chennai offers an insightful example. In 2020, as COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted lives and economies, the city’s food system came under sudden strain. The closure of Koyambedu market, one of Asia’s largest wholesale hubs and a vital artery for fresh produce, raised urgent questions: how does a metropolis like Chennai get its food?

The Urban Design Collective’s project, Who Feeds Chennai? emerged in response. The initiative traced the movement of vegetables, among other staples, and found that the city’s fresh produce was largely sourced from its peripheries as well as adjoining districts. Another study conducted by IIT Madras found that traders based in Koyambedu, many of whom are unionised, handle the logistics of transport. Smaller farmers unaffiliated with middlemen sometimes travel up to 200 km to reach the city. Certain vegetables were even found to travel over 1,000 km from northern India.

For most other cities, such mapping remains absent, due in part to the informal and fragmented nature of supply chains and the lack of institutional attention to urban food planning.

Staple grains were found to reach Chennai from further afield. While some rice is sourced from Tamil Nadu’s delta districts, much of it arrives from states like Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, Assam, and West Bengal, with brokers linking producers and Chennai-based millers. Wheat is mainly procured from Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh through similar channels. Pulses come from a mix of local sources and distant states such as Delhi and Haryana, as well as from international suppliers including the US, Canada, Australia, and Mozambique.

The city’s meat supply is more decentralised. Poultry, Chennai’s most consumed meat, is brought in from Tamil Nadu and nearby southern states, often through vertically integrated systems where companies provide chicks, equipment, and market access to local growers. Mutton, the second most popular meat, is transported over 2,000 km from states like Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra, while beef typically comes from Kerala. Fish arrives not only from the Coromandel Coast but also from other coastal regions, thanks to improvements in cold storage infrastructure.

Projects like Who Feeds Chennai? offer a rare glimpse into how food reaches an Indian city. For most other cities, such mapping remains absent, due in part to the informal and fragmented nature of supply chains and the lack of institutional attention to urban food planning.

Around the world, city governments are increasingly recognising the importance of understanding and managing how food circulates through urban systems. A leading example is the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, a global agreement signed by over 250 cities such as Milan, Nairobi, Rio de Janeiro, Seoul, Toronto, New York City, Dakar, Melbourne, and Amsterdam. Launched in 2015, the pact has supported initiatives worldwide to map food flows, strengthen urban–rural linkages, reduce waste, and improve access to nutritious food through public procurement and community-based programs. The Indian cities of Bhopal, Indore, Jammu, Panaji, Pune, Rourkela, Sagar, and Ujjain are also signatories. However, there is little publicly available information on whether these cities have undertaken detailed mapping of their food systems.

Also read: The circular bioeconomy movement can change how we see waste

As urban centres expand, they draw food, water, labour, and land from their margins, reshaping both agricultural production and everyday life. In the National Capital Region, rising urban demand has led to significant changes in land use in peri-urban regions, especially in Haryana. Farmers are increasingly turning to high-value crops like fruits and vegetables, aided by state support for polyhouse cultivation, horticulture promotion, and improved market access. These shifts are not only transforming cropping patterns but also strengthening local supply chains that feed the growing urban population.

However, risks remain: many smallholders face insecure tenure, erratic access to water, and volatile market conditions that limit long-term investment. As real estate interests encroach and cultivation becomes more marginal, benefits from intensified production are unevenly shared. Without more inclusive governance and safeguards for farming livelihoods, these shifts may deepen existing inequalities.

What enables economic survival in the short term may be contributing to long-term health and ecological decline.

In Bengaluru’s peripheries as well, food production has shifted away from traditional crops like millets and pulses towards high-value and high input-demanding crops like baby corn, mulberry, cattle fodder, as well as lawn grass. In particular, the rise of lawn grass cultivation for Bengaluru’s landscaping industry exemplifies a form of extractive agriculture that is ecologically damaging, socially disconnected, and diverts land that could otherwise be used to grow local food crops.

As a result of the city’s struggles with fresh water supply, agriculture in Bengaluru’s southern periphery depends on untreated or partially treated wastewater for irrigation. This has allowed farmers to cultivate year-round, boosting incomes and enabling diversification. But this practice is not without pitfalls. Vegetables and milk from these zones have tested positive for heavy metals, and residents report high rates of waterborne and skin-related illnesses. What enables economic survival in the short term may be contributing to long-term health and ecological decline.

Also read: The promises—and perils—of Indian aquaculture

Informal food networks, which take the form of streetside vendors and fish mongers, are central to how Indian cities eat. Unlike in many other parts of the world, large supermarket chains have failed to replace them, finding it hard to compete with the accessibility, affordability, and trust built into these local systems of provisioning. Though often overlooked in policy, informal food networks form a critical part of urban infrastructure, enabling both food access and livelihoods.

In cities like Mumbai, the informal food sector has been deeply shaped by the city’s history as an industrious port. Today, it is home to vibrant food networks that operate beyond the bounds of formal municipal governance but with a high level of coordination in how space and money are used.

Neighbourhoods like Dharavi, often reduced to shorthand for poverty or overcrowding, are also hubs of food processing, retail, and distribution. Dabbawalas, meanwhile, transport home-cooked lunches to offices across the city with remarkable precision, weaving through trains and traffic in one of the world’s most complex logistical systems.

Yet these systems remain precarious, and their workers vulnerable. Most vendors lack legal status, secure space, or access to basic infrastructure like clean water and waste disposal. Periodic evictions and restrictive regulations, often justified through concerns about hygiene or congestion, displace the very actors who make urban food access possible. These pressures are intensified by social hierarchies. Gender, caste, and migrant status influence who gets access to vending locations, how municipal authorities respond, and who bears the brunt of enforcement.

Kolkata offers a slightly different story. With over 3,00,000 vendors working across the city, street vending is just as widespread as other metropolitan cities, but more deeply tied to local politics. Over the years, hawkers have formed strong unions and built enduring ties with political parties. These relationships have allowed them not only to survive but also to resist eviction and, at times, gain influence over decision-making processes.

However, this visibility brings its own complications and power struggles. In many areas, clientelist politics now shape urban spaces wherein local leaders offer protection in exchange for votes. This means that basic services, rights, and fair treatment often depend on political loyalty rather than formal legal protection.

In 2014, India passed the Street Vendors Act, a national law aimed at recognising and protecting the rights of street vendors. It called for detailed surveys to register vendors, the creation of designated vending zones, and restrictions on evictions without due process. The law was intended to bring dignity and security to informal food work. But more than a decade later, implementation remains limited. Other kinds of food workers such as food delivery staff and domestic cooks also remain on the margins of labour protection, often navigating long hours, low pay, and few avenues for redress.

Also read: Can India’s traditional knowledge future-proof its food system?

As of 2025, urban food policy in India remains inconsistently implemented and disproportionately influenced by upper and middle-class interests, with little recognition of the informal actors who play a central role in enabling food access. A more inclusive approach must look beyond city centres and engage the wider geographies that feed them.

At a time when cities around the world increasingly turn to food imports to ensure food security—often adding to climate change—it is all the more important for India to draw on its rich biodiversity and traditional agricultural knowledge to meet urban food needs through domestic production.

Importantly, what becomes clear from examining India’s urban food landscape is that the path to improving it does not lie in replacing informal networks with privately led or corporate-controlled models. Rather, it lies in recognising that these networks of small traders, transporters, vendors, farmers, and millers form the foundation upon which urban food access depends. Far from being obsolete, they are resilient, adaptive, and deeply embedded in the country's social and economic life.

However, ensuring the rights and protections of those engaged in informal food work is not a call for deregulation, but for thoughtful, context-sensitive governance that values and safeguards these actors while addressing gaps in infrastructure, food safety regulation, transparency, and equity. Without such a framework, efforts to formalise or privatise the food economy risk excluding those who already deliver affordability and access to the majority of urban residents.

At a time when cities around the world increasingly turn to food imports to ensure food security—often adding to climate change—it is all the more important for India to draw on its rich biodiversity and traditional agricultural knowledge to meet urban food needs through domestic production. As a result of the country’s geographic and climatic diversity, a one-size-fits-all approach to urban food planning is unlikely to work. Policies must instead reflect regional specificities. Equally important is the need to curb corporate concentration in the food sector so that access to nutritious and affordable food is not limited to elites but extends to the working class. Encouraging the consumption of locally sourced foods through price incentives and public awareness can help align urban diets with regional food systems, supporting both sustainability and equity.

Artwork by Alia Sinha

{{quiz}}

Proteins are made of 20 building blocks. Your body only makes 11; the rest are on your dinner plate

Editor's Note: From grocery lists, to fitness priorities, and even healthy snacking, protein is everywhere—but do we truly understand it? In this series, the Good Food Movement breaks down the science behind this vital macronutrient and its value to the human body. It examines how we absorb protein from the food we consume, how this complex molecule has a role to play in processes like immunity, and the price the Earth pays for our growing protein needs.

Why has protein suddenly become the global poster child for modern nutrition? From nutritionists, to scientists, to artificial intelligence, everyone is invested in this macronutrient. In fact, one of AI’s biggest biology puzzles has become understanding how proteins fold into their unique 3D shapes.

Proteins are essential to our bodies. They build muscle, carry oxygen, fight infections, digest food, and even help our brains think. Essential components like enzymes, haemoglobin, hormones, muscles, and keratin—that constitute our organs, skin and hair—are made up of protein. The human body has over 20,000 protein-coding genes (segments of DNA that contain instructions on how to make proteins), and each protein serves a purpose.

But…what are proteins exactly?

The ways in which they fold (twist, curl and arrange themselves in 3D) determines what they eventually form, and how they function in the body—like enzymes, hormones and antibodies, among others.

Proteins are long chains made up of smaller molecules called amino acids. Think of amino acids like LEGO blocks—there are 20 kinds, and you can snap them together in endless ways to build thousands of different proteins. The ways in which they fold (twist, curl and arrange themselves in 3D) determines what they eventually form, and how they function in the body—like enzymes, hormones and antibodies, among others. But predicting this folded shape just from the sequence of amino acids is a complex affair.

(Note that proteins are infinitely varied and intricate—and this short explainer only scratches the surface. It’s like trying to describe the entire Internet using a sticky note. But hey, we’re trying.)

Also read: Protein’s seen and unseen benefits: How it affects metabolism, muscle repair

We need to know which amino acids build the protein molecule before predicting how it may fold. This is known as protein sequencing. Why is this important? To understand how a protein functions, how it interacts with other molecules, and how mutations may cause it to malfunction.

For instance, a single amino acid change in the haemoglobin protein leads to sickle cell disease, altering the shape and function of red blood cells. Insights like these help researchers develop targeted medications, study genetic disorders, and even design synthetic proteins from scratch—such as enzymes that break down plastic, or lab-made antibodies used in cancer immunotherapy. Essentially, protein sequencing helps understand life on a molecular level.

Insights like these help researchers develop targeted medications, study genetic disorders, and even design synthetic proteins from scratch—such as enzymes that break down plastic, or lab-made antibodies used in cancer immunotherapy.

The quest to sequence this macronutrient stretches back centuries. As early as 1789, French chemist Antoine Fourcroy noticed that substances like albumin, fibrin, and gelatin shared similar properties, though back then they were still called ‘Eiweisskörper’ (literally, ‘egg-white bodies’). A few decades later, in 1819, Henri Braconnot managed to isolate the first amino acids, leucine and glycine, from natural sources—hinting at the building blocks behind proteins.

The word ‘protein’ itself was coined in 1838 by Dutch chemist Gerardus Johannes Mulder, rooted in the Greek ‘of first importance.’ But it wasn’t until the 20th century that things really took off.

In the early 1950s, Frederick Sanger cracked the amino acid sequence of insulin, proving for the first time that proteins have precise, genetically determined structures. Around the same time, George Palade discovered ribosomes—the workers in our cells that assemble proteins based on instructions from our genes. Then in 1958, John Kendrew used X-ray crystallography to unveil the first detailed 3D structure of a protein—myoglobin from a sperm whale—ushering in the age of structural biology.

Fast-forward to 2020, DeepMind’s AI tool AlphaFold accurately predicted protein’s myriad 3D shapes from amino acid sequences—something that took labs years to figure out. In 2021, it released structures for over 200 million proteins (essentially covering every protein known to science today), transforming the way we understand what our bodies are made of.

Also read: Whey to go: A complete guide to protein

Okay, quick recap. Remember those 20 amino acids that are the building blocks of protein? Out of these, 9 are ‘essential’; your body can’t make them. You have to get them from food. The other 11 are ‘non-essential’; your body can process them from other nutrients like carbohydrates and fatty acids.

This is why pairing foods matters. If you're vegan, aim to combine grains, legumes and nuts/seeds across meals. A classic example is rajma and rice, or the old American favourite, a peanut butter sandwich. If you're vegetarian, adding a little dairy simplifies things a lot.

Not all protein sources give you all 9 essential amino acids. Foods like meat, fish, eggs, dairy are called complete proteins because they check all the boxes. But most plant-based proteins are incomplete, which means they’re missing one or more of those 9 essential amino acids.

This is why pairing foods matters. If you're vegan, aim to combine grains, legumes and nuts/seeds across meals. A classic example is rajma and rice, or the old American favourite, a peanut butter sandwich.

If you're vegetarian, adding a little dairy simplifies things a lot. Some go-to combinations include moong dal cheela (soaked mung bean crepes) and pairing it with curd or yogurt. Another excellent option is chole (chickpea curry) served with whole wheat roti and a side of buttermilk, offering a balanced and protein-rich meal. Similarly, moong dal khichdi paired with lightly grilled paneer cubes creates a wholesome lunch packed with protein and essential nutrients.

What happens if you don’t get enough protein? Well, protein deficiency hits hard and fast. You feel weak, tired and your immune system tanks – you catch colds quicker, and your injuries are slower to heal. In children, physical growth becomes stagnant and their brains lag behind. In extreme cases, it can lead to kwashiorkor, a condition where children have bloated bellies, thin limbs, and severe health problems.

Also read: Is your body low on protein? Signs and impacts of a deficiency

{{quiz}}

Pulses are a crucial source of protein. But in India, their consumption remains troublingly low

When it comes to meeting individuals’ bodily protein requirements, pulses play a crucial role—particularly in the case of vegetarian individuals. When combined with cereals, they significantly complement the proteins contained in them, resulting in a more wholesome diet.

A 2022 publication by the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NAAS) states that pulses play a key role in reducing significant ailments and diseases. “Eating pulses along with Vitamin C-rich foods enhances absorption of iron, rendering pulses a potent food for preventing anaemia. Pulses being high in fibre, low in fat and with a low glycemic index, are thus an ideal food for weight management, particularly for the diabetic patient,” the authors of the publication, titled Sustaining the Pulses Revolution in India: Technological and Policy Measurers, write.

They add that the high fibre content in these legumes lowers low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, reducing the risk of coronary heart disease. Per the publication, pulses also contain phytochemicals and antioxidants, which lend to them anti-cancer properties.

“Being leguminous crops, possessing root nodules, they fix and utilise atmospheric nitrogen. They are thus not dependent on industrially fixed nitrogen, a process requiring energy, but add up to 30 kgs of nitrogen per hectare to the soil and improve its fertility,” writes Dr. S. Ramanujam in a chapter from the Handbook of Agriculture published by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR).”

Dr. Ramanujam goes on to give more specific uses of various pulses. Black gram (urad) is very rich in phosphoric acid. Germinated seeds of Bengal gram (chana) are recommended to cure scurvy, while the malic and oxalic acids found in its green leaves are prescribed for intestinal disorders. Moth beans, also known as matki beans, are among the most drought-resistant pulses. Due to its low, trailing, mat-like growth, it is very helpful against wind erosion in sandy areas where it is grown more extensively.

In the case of pigeon pea (arhar), the green leaves and tops of the plant are fed to animals or utilised as green manure. Dry stalks obtained after threshing are used for basket-making or as fuel and thatching material. A deep-rooted crop, arhar is also planted as a soil rejuvenator to break up the hard subsoil, and as a hedge to check erosion. The heavy shedding of its leaves adds considerable organic matter to the soil.

Apart from their significant contribution to nutrition, there are many other benefits of pulse crops. Due to their nitrogen fixation abilities, pulses contribute significantly to lowering the dependence on chemical fertilisers when grown in rotation with cereal crops or as mixed cropping. This, in turn, helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Also read: Protein’s seen and unseen benefits: How it affects metabolism, muscle repair

Given these multipronged benefits, it is not surprising that traditionally, India’s farmers have grown a wide diversity of pulse crops, particularly in mixed farming systems, and in rotations well adapted to local conditions. These pulses have been much valued in local food habits too, being processed and cooked into hundreds of cherished dishes, including snacks like papads with longer shelf-lives, as well as the preparation of green pods of some pulses as nutritious vegetables.

Unfortunately, several factors have contributed to a stagnation in the production of pulses and a decrease in per capita availability in recent decades. Simultaneously, because of the lower per capita availability, the dependence on imported pulses has increased.

According to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the consumption of pulses at a rate of 68 gms per capita per day has been recommended in India. As against this desirable norm, the actual per capita availability of pulses was as low as 43.83 gms per day in 2015-16. Data from the National Sample Survey on Consumption Expenditure (2011-12) indicated even lower availability—citing 27 gms per capita per day as actual consumption.

In 1956, the per capita per day net availability of pulses in the country was 70 gms per day, or slightly higher than the desirable norm suggested by the ICMR. The decline from 70 to 47 today is unfortunate.

According to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the consumption of pulses at a rate of 68 gms per capita per day has been recommended in India. As against this desirable norm, the actual per capita availability of pulses was as low as 43.83 gms per day in 2015-16.

From 1961 to 2015-16, the cereal production in the country increased by 239%, while the production of pulses increased by only 29%. Whether we look at increase in area or productivity, the situation reveals stagnation.

With the advent of the Green Revolution in the 1960s and the ‘70s, there was an increased tendency towards vast monocultures of crop varieties with a limited genetic base. In contrast, the mixed cropping systems and rotations that had evolved over several centuries, taking into account the multiple needs—including soil fertility and water conservation—were ignored. In this process, the cultivation of pulses was reduced significantly, with all the accompanying adverse impacts on nutrition and the environment. In Punjab, the state that led the Green Revolution, in 1966-67, pulse crops were grown on 13.4% of the total area under crops, but by 1982-83, this had dropped to just 3%—a massive change within just about 15 years.

Also read: Why bajra, the ‘pearl’ of India’s millets, remains underutilised

As a result, there isn’t just a lower per capita availability of pulses today, but even at this low level of consumption, there is increasing dependence on imports. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, India accounts for approximately 39% of the global demand for pulses, but contributes to only 28% of their production worldwide.

There is a very strong case for formulating a comprehensive strategy to increase local production of pulses in safe and healthy ways, thereby making a very significant contribution to promoting nutrition and protecting the environment.

Understandably, then, this is reflected in increasing imports of pulses, thereby increasing pressure on foreign exchange in an area where the country has the potential to achieve self-reliance. “India's pulses imports in fiscal 2024 surged 84% year-on-year to their highest level in six years after lower production prompted India to allow duty-free imports of red lentils and yellow peas, government and industry officials said on Thursday,” reads a report from The Hindu. The cost of these imports increased from $1.83 billion in 2013-14 to $5.48 billion in 2024-25.

Imports included about 2.2 million tonnes of yellow/white peas from mainly Canada and Russia, 1.6 million tonnes of chana from Australia, 1.2 million tonnes of arhar mainly from African countries, 1.2 million tonnes of masoor from Canada, Australia and the USA, and 0.8 million tonnes of urad from Myanmar and Brazil.

Apart from economic costs, rising import demands raise concerns about monitoring quality and safety—concerns that have emerged from time to time. In exporting countries, where pulses are not a staple food, there is a higher possibility of safety and health precautions being violated.

There is a very strong case for formulating a comprehensive strategy to increase local production of pulses in safe and healthy ways, thereby making a very significant contribution to promoting nutrition and protecting the environment. In this effort, we can learn much from traditional practices, particularly mixed cropping systems and crop rotations, as these provide valuable insights into which pulse crops can be best grown in combination with cereals and other crops in specific locations.

A highly decentralised approach is needed, with programmes prepared through adequate consultation with local farmers, particularly elderly and experienced farmers, including women. The government should take steps to encourage pulse production by ensuring proper prices in the market and procure pulses for supply to weaker sections of society through the public distribution system. In addition, farmers can secure better returns if local, village-level processing of pulses is promoted.

Also read: ‘Summer ragi’: How Kolhapur farmers’ millet experiment became a success story

{{quiz}}'

(Additional editing by Neerja Deodhar)

Hidden in plain sight, greens like taikilo and alu have defined local diets and history

It was a heritage awareness walk held in the semi-forested area of Pernem in North Goa, in June. The monsoon season had just begun, making the scenery lush and green. While admiring this greenery, something caught the attention of Neeta Omprakash, an independent visual arts researcher and lover of wild greens. She immediately reached for a small kitchen knife and a bag, and foraged for the young, tender leaves of ‘luti’ or dragon stalk yam (Amorphophallus commutatus)—the plant that had made her pause.

Some of her fellow walkers were amazed by this sight, but for Omprakash, foraging is an annual tradition when monsoon clouds arrive in Goa. “I eagerly wait for the first week of rain, as it is the time when the first shoots of luti break through the tough crust of earth to emerge,” says Omprakash, a Panaji resident who loves to cook this vegetable which she describes as “highly aromatic.”

She prepares it by first soaking the leaves overnight, with a few peels of kokum, which helps prevent skin irritation (the presence of calcium oxalate crystals in luti are neutralised by souring agents like kokum). She then cooks it with coconut, jackfruit seeds, garam masala, ‘kuvalyachi vadi’ (a condiment made from ash gourd), and then tempers it with coconut oil and garlic. “Once garlic is tempered in coconut oil, the aroma takes over the entire home! I have never missed an opportunity to eat luti bhaji,” adds Omprakash, who has a love for foraging wild produce.

In Goa, ‘monsoon greens’ have their own fan base. The season for these vegetables and leafy greens begins in June and lasts until August, as they are best consumed while they are still tender. Local beliefs state that one must eat these greens at least once during the rainy season.

A variety of greens can be found in the state, each specific to its particular region, making some of them hyperlocal. The commonly found ones are the leaves of ‘tailkilo’ (Cassia tora), ‘kisra’ (moringa), ‘kuddukechi bhaji’ (Celosia argentea or cock’s comb), and tender shoots of ‘akur’ or mangrove fern (Acrostichum aureum). Alongside these, wild fruits such as ‘fagla’ or spiny gourd are also consumed. The leaves and shoots of the Colocasia (arbi) remain a widely consumed favourite, as they grow wild along roadsides, farms, and open spaces. There are around six edible varieties of Colocasia that are eaten in Goa, including ‘tero’, ‘alu’, ‘tirpatche alu’, and ‘vatalu’, which have medicinal properties and grow on tree trunks in deep forests.

For many Goans, cooking these vegetables is a means to feel connected to their land and its resources. It is also an attempt to document culinary traditions and conduct further research into them.

“I usually forage Colocasia from my backyard, and other monsoon greens from forests. I hardly buy any edible greens during the monsoon,” says photographer and local cuisine enthusiast, Assavri Kulkarni. She cooks Colocasia leaves with souring agents like ‘aambade’ or hog plums. These vegetables have alkaline properties that can irritate the throat when eaten; souring agents can help to combat this irritation. The other commonly used souring agent is kokum peels. Along with these souring agents, jackfruit seeds are used to add an element of flavour and texture. Additionally, Kulkarni sometimes adds peas or dried shrimp for their protein content.

“I also make ‘alu vadi’ for my daughter’s tiffin,” says Kulkarni. She loves to experiment with wild greens, preparing dhoklas and sweet pancakes with taikilo leaves. She also loves to cook akur during this season, either by frying it or adding it to pulaos or curries like ‘alsanyache tonak (a curry made from local beans called ‘alsane’). She even pickles them—a recipe she confirms is born out of trial and error.

For many Goans, cooking these vegetables is a means to feel connected to their land and its resources. It is also an attempt to document culinary traditions and conduct further research into them.

Also read: Foraging in Bengaluru: A source of sustenance, flavour

School teacher and folk art researcher Shubhada Chari enjoys discussing rare greens, in an effort to share this knowledge with others. In the course of her documentation efforts, she has encountered insightful anecdotes, such as how the names of some villages are possibly derived from these foraged greens. She mentions a creeper called ‘ghotvel’ (Smilax ovalifolia), whose maroon-hued leaves are a seasonal delicacy. “There’s a village called Ghoteli in the Sattari taluka, and locals say that its name comes from this creeper as it is commonly found here,” says Chari.

The fate of a village named Pendral and a fruit called ‘pendro’ is believed to be similar. “Intriguingly, this fruit can easily replace potatoes in dishes,” adds Chari. Pendro is harvested in the monsoon and prepared by boiling and peeling off its outer skin which is not safe for consumption. Its core—with a texture resembling a potato’s—is edible. The forest dwellers of Sattari have long included this fruit in their diets.

Chari adds that the leaves of ‘bonkalo’ (Cheilocostus speciosus), commonly known as crêpe ginger, also find a place in her kitchen. These leaves possess a slight sourness and are often cooked with tur or moong dal.

Bamboo shoots—cut and added to curries, brined in salt water, or shallow fried—are also traditionally consumed in Goan villages. Chari informs that locals usually use two bamboo species for this—‘kankiche bamboo’ (Dendrocalamus strictus) and ‘chivar’ (Oxytenanthera ritcheyi). They also cook pods of the ‘kuda’ (Holarrhena pubescens) tree as a vegetable at this time of the year.

Journeys into the forested areas of Sanguem, Quepem, and Canacona reveal a variety of hyper-local greens. Residents here, typically tribals of the Velip community, have been foraging these greens for generations, guided by indigenous knowledge passed down through generations. They have relied on these food sources during torrential, stormy monsoons. The establishment of the ‘Ran-Bhaji Utsav’ gives locals a chance to showcase the biodiversity of their lands; an annual wild greens festival held at Canacona, it is organised by the Adarsh Yuva Sangh cultural group in collaboration with the Goa State Biodiversity Board and the Agriculture Department. It is an opportunity to display vegetables that city dwellers have neither heard of, nor seen.

The festival’s third edition, held on 19 July 2025, brought forth at least 40 types of forest and wild leafy vegetables like ‘teniya bhaji’, ‘ek pana bhaji’, ‘harfule bhaji’, ‘merevaili/gundure bhaji’, ‘kodvo bhaji’, ‘chaie bhaji’ (a vegetable preparation of tubers), ‘chudtechi bhaji’, ‘kayriyo’ (seeds of Entada Scandens, which are boiled and cooked), and shirmundli (a wild creeper found in the forest).

In some villages of Canacona, the tender stem of the wild banana plant, known as ‘ghabo’, is also consumed during the monsoon. Harvested during the budding of the banana flower, it is added to the local vegetarian delicacy ‘khatkhate’.

Along with leaves and stems, wildflowers of plants like ‘churchurechi fula’ (Pavetta indica) are also consumed.

Also read: Protecting place and power, not people: The trouble with GI tags

While accounts of these wild greens may paint a thriving picture of Goa’s biodiversity, much of the state is constantly under threat due to concretisation and urbanisation. As per the 2011 Census, 62% of the state’s population was already urbanised. A population projection report released in 2020 predicts that by 2036, 88% of the state’s residents will live in towns and cities.

Chari, who frequents Goa’s forests, attests to the decrease in proportion of wild greens owing to habitat loss. “Nowadays, construction can be observed even in forested areas. In the summers, some villagers light forest fires to clear land for farming, which results in the burning of seeds that would otherwise have sprouted in the monsoon,” she states.

Moreover, awareness about monsoon greens is lacking in urban and semi-urban areas. Miguel Braganza, formerly an officer with the Agriculture Department of Goa and Secretary of Goa’s Botanical Society, states, “Common veggies like taikilo and kudduko, once commonly found even on roadsides, are becoming rare. [In recent times] panchayats and municipalities have used brush cutters to clear open spaces. The regeneration of these plants is not taking place.” Brush cutters are employed for aesthetic reasons and out of a belief that the proliferation of wild greens will attract snakes and other creatures.