Bharadwaj has successfully developed varieties which maintain high yields even in drought-prone areas

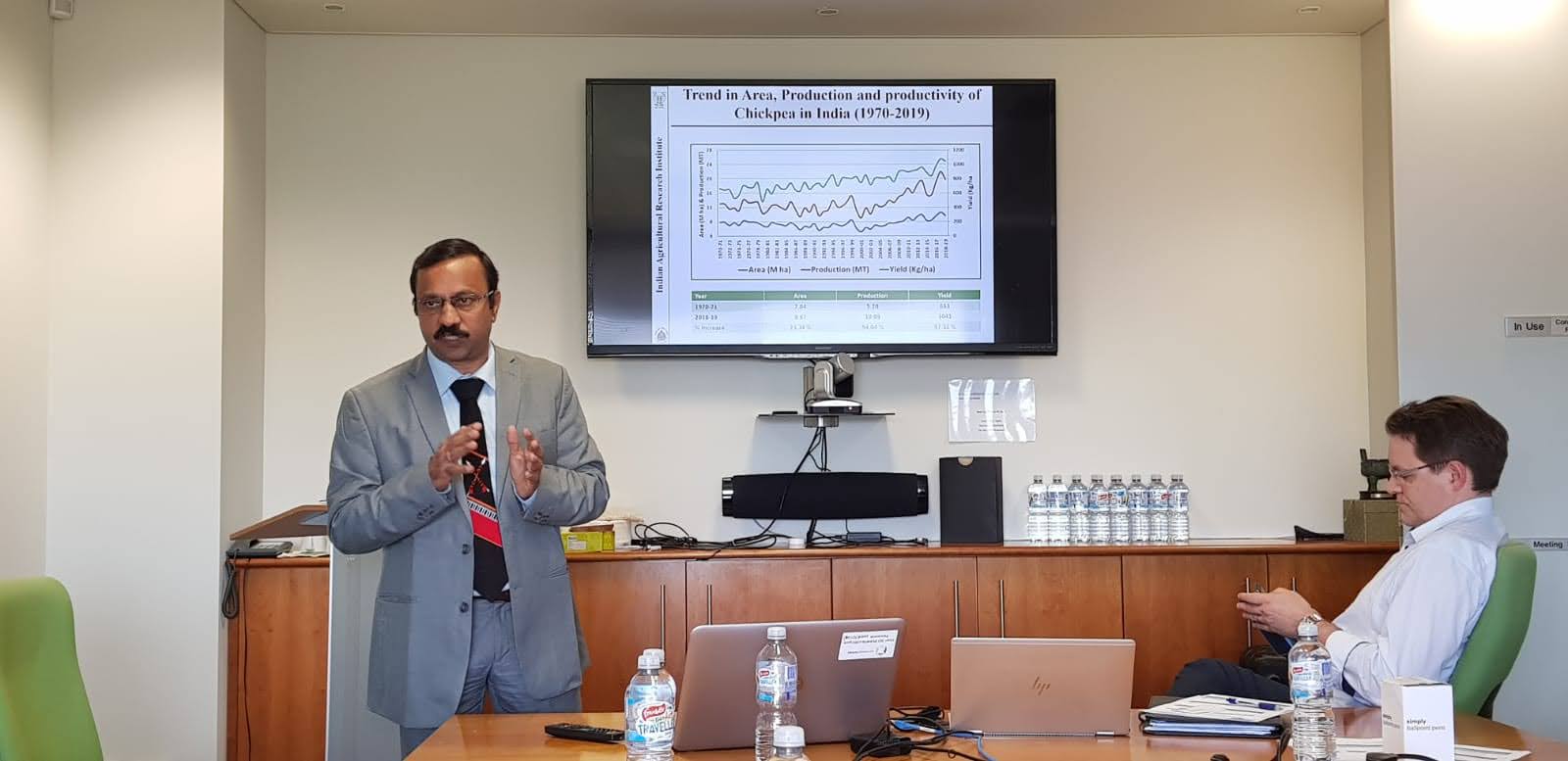

For the last 27 years, Prof. Chellapilla Bharadwaj has been working on chickpeas. Principal scientist with the Genetics Division at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), he holds a PhD in genetics and plant breeding. A crop expert interested in technological interventions, he is now engaged in research to breed superior varieties of the legume that can stand the test of climate change. In fact, the varieties developed by Prof. Bharadwaj now make up a third of chickpeas grown in central India.

His summer visits to the remote, picturesque Araku region in Andhra Pradesh, where one his relatives worked under the tribal development programme a few decades ago, sparked his interest in agriculture. His choice to study chickpeas emerged from a larger fascination with pulses. Significantly, Prof. Bharadwaj’s work with chickpeas is also focused on smallholder farmers; his varieties are meant to help them increase their yields and consequently, their incomes. Since the chickpea is a climate-resistant crop, his objective is to develop varieties of this crop that can help small farmers, who will be most affected by climate change.

There are two distinct types of chickpeas: the smaller black variety, called the desi chana, and the other variant which is bigger in size and lighter in colour, called the Kabuli chana. The latter is sweeter in taste and does not become sticky upon cooking. While desi chana is cultivated in India and Pakistan in significant quantities, Kabuli chana is native to the Mediterranean.

Significantly, Prof. Bharadwaj’s work with chickpeas is also focused on smallholder farmers; his varieties are meant to help them increase their yields and consequently, their incomes.

When it comes to the cultivation of pulses in India, almost 50% of production as well as area under farming belongs to chickpeas. The country is both, the largest producer of chickpea in the world, as well as its biggest importer. Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan are the leading states in its cultivation. It is typically grown as a Rabi crop; it prefers dry weather and deep, loamy soils. There are now over 200 commercially available chickpea cultivars being grown in India, with the protein content in some of these touching nearly 33%, with exceptionally high bioavailability. Generally, the pulse is also high in dietary fiber and unsaturated fatty acids, as well as micronutrients such as iron, zinc and magnesium.

Legend has it that the chickpea, known for its diversity and cross-cultural travels, became Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s source of sustenance after he was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb. When his son gave him the choice to pick only one ingredient, Shah Jahan supposedly opted for the legume because it can be cooked in numerous ways. Even a story this medieval simply illustrates what Prof. Bhardwaj believes about the chickpea: it’s a genius food. It can be prepared and consumed in any way one likes. It’s no surprise that it adapted so readily to a variety of regional culinary practices.

In recent years, increasing yields and building climate resilience have become a priority for its farmers. This is a priority for Prof. Bharadwaj, too. Led by him, his team works with precision to reach these two goals. For instance, when working on developing drought-tolerant varieties, specific genes that impart this advantage–like deep root lines–are identified, and used to breed new varieties. Traditionally, this sort of cross-breeding would take about 10 years. But Prof. Bharadwaj’s team uses molecular markers to identify genetic information, and breeding this way cuts the development time in half. This process of genomic breeding is also being used to develop varieties that not only resist drought, but also wilt–the same variety offers higher yield, as well. Of the 28 varieties developed by the team, six are bred this way.

In this conversation with the Good Food Movement, Prof. Bharadwaj explains how they achieved these outcomes.

What place does the chickpea occupy in Indian agriculture? How does it compare to staple crops like paddy and wheat?

Each crop has its own distinct role to play in the food system. While rice and wheat meet the carbohydrate requirements, the chickpea plays a vital role in fulfilling the protein needs of crores of Indians.

In the northern and the western plains of India, chickpea cultivation has declined.

It is one of India’s most important pulses. All over the world, it is cultivated over 11–13 million hectares, which is a large area by global standards. Grown under resource-limited conditions, chickpea thrives due to its low input requirements and unique ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. It thereby enriches soil fertility.

However, a transformation has come about. In the northern and the western plains of India, chickpea cultivation has declined. The crop has been largely replaced by the rice–wheat cropping system. This shift has contributed to significant environmental concerns like soil degradation and a depletion of water resources. To address these challenges, it is essential to reintroduce at least one pulse crop—preferably the chickpea—in the Rabi season. Policy interventions and institutional support are needed to ensure the revival of chickpea in these two regions.

Also read: The big promise of the little millet, in Odisha and beyond

It is known to be a climate-friendly crop. Is your work building on the science needed to make it more resilient to climate change?

I am engaged in enhancing the resilience of the chickpea to make it adaptable to various climatic vulnerabilities. It requires minimal external inputs. My research extends beyond merely identifying these superior genetic resources–I am also strategically deploying them to breed superior chickpea varieties capable of thriving under challenging environmental conditions.

Using advanced molecular breeding tools, I have successfully developed several varieties such as Pusa 10216, Pusa 4005 and Pusa JG 16. The Pusa 10216 shows better drought resistance as well as higher yields, and it was released by ICAR in 2019. The other two are more recent: Pusa 4005 was released in 2021, and Pusa JG 16 in 2023.

These varieties possess the ability to maintain high yields even in drought-prone areas. They offer farmers reliable options in the face of climate variability. Central India, where these varieties have been primarily adopted, have seen an increase in their chickpea yield by nearly 25%. Pusa 10216, specifically, showed an 11% yield superiority compared to its predecessor in the very year it was released.

Also read: Why kokum, a beloved souring agent, hasn't evolved into a commercial success

Could you comment on the chickpea’s genetic diversity (variety of genes that help the crop adapt, survive, evolve)?

Cultivated chickpea varieties possess relatively narrow genetic diversity. However, the species as a whole harbours rich genetic variations which are largely found in traditional landraces and crop wild relatives or CWRs (a wild plant closely related to the domesticated plant). Although the natural habitats of many CWRs are on the verge of extinction, they have been conserved in gene banks. These genetic resources must be systematically characterised and effectively utilised in breeding programmes to enhance the crop’s resilience and productivity.

What technology do you use in your work?

At the IARI, I am dedicated to developing superior chickpea varieties tailored to diverse market segments and suited for farmers across all the chickpea-growing zones of India. The breeding programme, ‘Genetics and Genomics Approaches for Breeding Chickpea to Enhance Productivity, Stress Resilience, and Nutritional Quality,’ integrates cutting-edge genomic tools with conventional breeding methods. By combining traditional selection practices with genomic-assisted breeding, I aim to deliver high-yielding, climate-resilient, and nutritionally enriched chickpea varieties that meet the evolving needs of farmers and consumers alike.

Why are so many scientists across the world invested in the chickpea?

It is one of the most important legume crops. India plays a key role in its global value chain as the largest producer, consumer, importer and also a significant exporter. While India exports the large-seeded Kabuli type, it also imports substantial quantities of the desi (kala chana), making the Indian market a focal point of global trade. This attracts major chickpea-producing countries such as Australia, Tanzania and Ethiopia, all of whom aim to cater to the Indian demand.

With the rising protein market and increasing emphasis on sustainable agriculture, it offers immense potential for both food security and environmental resilience.

Beyond its commercial significance, its exceptional nutritional profile–particularly its high protein content–positions the chickpea as a key player in addressing malnutrition and in meeting the growing global demand for plant-based protein. With the rising protein market and increasing emphasis on sustainable agriculture, it offers immense potential for both food security and environmental resilience. These combined advantages explain why scientists worldwide are investing in chickpea research.

The chickpea travelled from the Mediterranean region to Afghanistan and then entered India. What do you have to say about this fascinating journey across cultures? What made it a cross-cultural crop?

The journey of the chickpea is a remarkable instance of how a humble crop can weave itself into the cultural fabrics of multiple civilisations. This migration was not only about seeds moving across continents, but also about knowledge, cuisine and culture traveling together. Along the ancient trade routes, chickpea was not only a food commodity, but also a strategic agricultural product that could be stored, transported and traded easily.

Its ability to thrive in semi-arid conditions, with modest water and nutrient needs, allowed it to adapt seamlessly from the Mediterranean’s mild winters to the harsher terrains of Central and South Asia. As it is rich in protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals, the chickpea met a fundamental dietary need across societies, both as a staple for vegetarian communities in India, and as part of balanced diets in the Mediterranean and the Middle Eastern regions.

Few crops can boast of a culinary range as wide as the chickpea.

Few crops can boast of a culinary range as wide as the chickpea. One only has to think of the Mediterranean hummus and the Levantine falafel to the Indian chana masala and besan-based evening snacks. Each culture reimagined the chickpea to suit its tastes and traditions. In essence, the chickpea’s cross-cultural journey is a story of resilience, adaptability and universal appeal. It is a crop that transcended geography to become a shared heritage of human food culture.

Also read: The nutritional power of ragi: India's overlooked supergrain

Why aren’t pulses mainstreamed in India? Even in dry regions such as Bundelkhand, one observes farmers opting for wheat. Why don’t they turn to chickpeas?

Wheat and rice have become easy crops to cultivate, as the expertise required to farm them is well understood. Their high adaptability, coupled with assured market support and government subsidies makes them the preferred choice for many farmers. In contrast, pulse crops, though hardy and resource-efficient, demand a certain level of farming skill and experience for successful cultivation. Farmers need to be educated and trained not only in pulse production techniques, but also in understanding the environmental benefits that pulses offer.

Unlike wheat and paddy growers, pulse farmers use far smaller amounts of nitrogenous fertilisers like urea. Therefore, fertiliser subsidy policies should be revisited to provide higher and more remunerative minimum support prices (MSP) for pulse growers. Additionally, imposing higher import duties on pulses can help protect domestic producers, ensuring that they receive fair and competitive market prices. With these targeted interventions, the area under pulse cultivation and overall production can be increased.

Edited by Anushka Mukherjee and Neerja Deodhar

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

.png)