Habitat degradation and a slow approach to conservation and aquaculture have put the beloved Pearlspot or Green Chromide at great risk

In the brackish backwaters of Kerala, there exists a fish so beloved that songwriters liken it to the kohl-lined eyes of women. A culinary superstar and heritage treasure akin to Bengal’s Hilsa, to eat it is to consume a part of Kerala itself: a product of a terroir that carries within it the sweetness of fresh water and the salt of the sea. When it arrives on the dinner table stewed in spiced coconut milk or wrapped in a banana leaf, a story far older—and stranger—than any recipe begins to unravel.

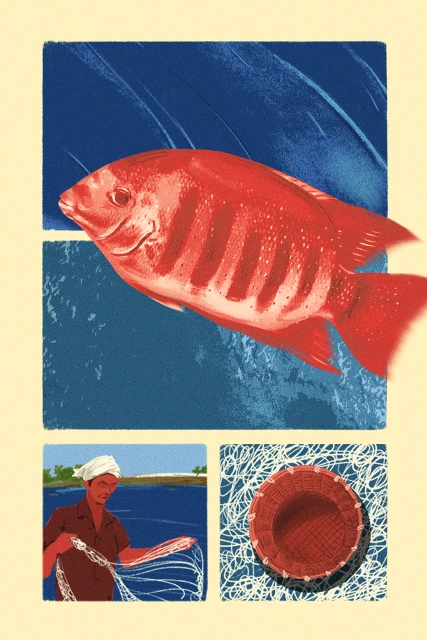

The fingerlings of the Pearlspot or Karimeen, the young of the fish just one stage away from being adults, are tender ghosts of the mangrove's shade. The fish thrives in the fragile balance between two worlds—gliding the cool currents of the shallows where rivers first yield, as well as the waters of the briny sea.

The Karimeen's ancestors swam in the Tethys Sea, the ancient ocean that once separated the northern and southern supercontinents. When Gondwanaland, the primordial landmass that cradled India and Madagascar together, began its slow fracturing millions of years ago, these fish adapted, evolved, and learned to thrive in the shifting salinity of brackish waters. They became euryhaline survivors—creatures equally at home in freshwater and saltwater, embodying in their very biology the secrets of a continent's rupture.

But today, as Kerala's backwaters face unprecedented stress, from pollution to damming, from agricultural runoff to urban sprawl and the entry of invasive piscine species, the Karimeen finds itself swimming through a radically altered world. The fish that once filled nets and pots in such abundance that it defined regional cuisine, has now grown scarce. A reminder that even creatures shaped by millions of years of evolutionary adaptation can falter when change accelerates beyond their capacity to respond. “We can’t rely on the Karimeen alone for our livelihood like we used to,” says Arun, a fisherman who operates out of Fort Kochi. Originally from Vypeen, an island in Kochi’s backwater estuary, Arun started fishing Karimeen at the age of 10 with his bare hands.

They became euryhaline survivors—creatures equally at home in freshwater and saltwater, embodying in their very biology the secrets of a continent's rupture.

The process, called Thappal, is intimate and arduous, Arun explains. Fisherfolk stand waist-deep in silt-heavy backwaters with their bare legs serving as anchors, while their arms plunge deep into the muck. Groping with fingers spread wide, gently sweeping the opaque bottom, they feel for the current of life: the twitch of a tail fin, the subtle shift in the mud, or the sudden warmth of a body against the cooler silt.

This practice, often carried out by experienced fishermen, involves casting a weighted circular net into the water, letting it sink and spread, and trapping the fish underneath before catching them by hand. Some others use cage-like traps in shallow waters that are baited and left overnight.

But, in the spawning period, if one is not careful of overfishing, fishing itself could become unsustainable. “Back in the day, my father only caught Karimeen and that was enough. As a kid, I’d accompany him. But now, we do all sorts of jobs just to get by,” says Arun, now in his 40s.

{{marquee}}

A geological puzzle

Beyond its culinary significance and contribution to livelihoods, the Karimeen is a living relic—a key to unlocking the mysteries of the Earth’s ancient past. In 2012, Scottish geologist Iain Stewart visited Kerala with his BBC crew while filming Rise of the Continents, a documentary series exploring the origins of Earth’s landmasses. His journey to the southernmost tip of India was a quest to understand the Karimeen and its evolutionary significance. Thriving in Kerala’s backwaters, the fish could hold a vital link to Gondwanaland.

Stewart traced the Karimeen’s evolutionary ancestry over 100 million years to the Tethys Ocean, which separated Gondwanaland from Eurasia. As the Indian landmass drifted northward, the fish’s relatives remained scattered across the remnants of Gondwanaland, evolving in isolation. Today, the Paretroplus cichlids of Madagascar are the Karimeen’s closest cousins, a living testament to how geological upheavals shaped biodiversity across continents.

Scientifically known as Etroplus suratensis or Green Chromide, Karimeen is the largest cichlid fish endemic to Peninsular India and Sri Lanka. The fish has an elevated, laterally compressed body and a small cleft mouth. Primarily found in the brackish waters of estuaries, lakes, wetlands and rivers in Kerala, the Karimeen holds cultural and economic importance in the region.

As a bottom feeder—scavenging from the seabeds of waterbodies for food—the Karimeen benefits from the availability of an abundance of nutrients, enabling it to grow quickly and thrive.

It develops through about six life stages: after the egg hatches, the larvae—colourfully called the “wrigglers”—start writhing in six days’ time. In a few weeks, the young learn to tolerate salinity and start swimming freely; they feed on zooplankton, insect larvae and algae, depending on their age. The next stage is the fingerling, when the fish is a few months old; it starts resembling the adult with faint shadows of its characteristic spots. Fingerlings are often fished and stocked for aquaculture, carefully grown in supervision until maturity in a tank or controlled lake, as opposed to open waters. After a year of age, the Karimeen is an adult, soon ready to reproduce. The average adult is about the size of a grown man’s hand.

A euryhaline fish, Karimeen can tolerate a wide range of salinities by actively regulating its internal salt and water balance through osmoregulation—an essential adaptation for survival in fluctuating aquatic environments. The fish’s elliptical body features shiny spots which lend it its English name, Pearlspot. Soft with flaky meat in a maze of strong, sharp bones, the fish is incredibly delicious, although some may find it slightly challenging to eat.

“Even though it’s found in states like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, the Karimeen thrives in brackish water and certain freshwater sources of Kerala. Places like the Kochi backwaters are an ideal habitat for the fish because they are rich in organic matter. These backwaters receive drainage as well as organic nutrients from the rivers connected to them, creating fertile waters,” says Vishnu Bhat, former Fisheries Development Commissioner. He explains that as a bottom feeder—scavenging from the seabeds of waterbodies for food—the Karimeen benefits from the availability of an abundance of nutrients, enabling it to grow quickly and thrive.

Notes on Cichlid Fishes of Malabar by N. P. Panikkar, a former Inspector of Fisheries in Travancore, details the reproduction, life history, and unique nest-making habits of the Karimeen. He explains how during breeding season, the Pearlspot pairs seek shallow, shaded areas to deposit their eggs on surfaces like stones, wood, coconut husks, or leaves submerged in less than three feet of water. They roughen smooth surfaces by biting them and clean the chosen area by removing dirt or vegetation. If the surface is too low, they excavate a cup-like depression in the ground. Both partners prepare the nest, and the process takes three to five days. This meticulous nesting behaviour not only highlights the species' adaptability, but also its instinctive resilience.

The fish also boasts unique anatomical features that set it apart. For instance, its anal fin, located at the rear end, is adorned with several spines—far more than the three or four typically found in other cichlids. Another evolutionary marker is its swim bladder structure, a trait shared only with the Paretroplus cichlids of Madagascar swimming 4,000 kms away. The membranous, gas-filled sac helps the fish maintain its buoyancy in water. No wonder Stewart called it a “creature that provides a direct link back to the most important event in the formation of Eurasia.”

The fish also boasts unique anatomical features that set it apart.

The same event is explained in Pranay Lal’s Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent, where his skillful recounting of the subcontinental separation helps link the Karimeen fish to Bengaluru’s late afternoon rains. The two are tied together by a historical event that is marked by the Palakkad Gap—a low, 30 km-mountain pass in Kerala’s Western Ghats. This geological feature was formed 88 million years ago when the Indian subcontinent separated from Madagascar: the same event that slowly transformed a branch of the ancient cichlid fish family into the Karimeen. The break in the ghats formed by the Palakkad gap actually allows the moist Arabian Sea winds to bring rain to Bengaluru, tying the city’s weather to an ancient geological period.

The Western Ghats' Palakkad Gap and Madagascar's matching Ranotsara Gap are twin escarpments that mark where the continents once joined. A fish, a city's rainfall, and a continent's fracture—all connected across millions of years.

Written into history

The ‘Karimeen’ was first described by the German ichthyologist (a branch of zoology devoted to fish) Marcus Elieser Bloch in 1790, in the fourth volume of his 12-volume treatise on fish: Naturgeschichte der ausländischen Fische. Etroplus suratensis, the genus name of ‘Karimeen,’ originates from the Greek words ‘etron’ (belly) and ‘oplon’ (arms), referring to the spines on its anal fin. But the word suratensis in the genus name is surprising: it refers to the city of Surat, Gujarat, which was the ‘type locality’ of the fish–the place from where the specimen was probably shipped to Bloch.

The Madras Aquarium Report of 1921 also lists the Karimeen as a regional food source.

Although the Karimeen was officially declared the State Fish of Kerala only in 2010, its popularity predates this recognition. From books and movies to film songs and folklore, this ‘star’ fish is inextricably linked to Kerala’s cultural identity. For instance, these lines from a 1979 film song are a sort of a kitchen anthem for Malayalis: “Ayala porichathundu karimeen varuthathundu kodambuliyittu vecha nalla chemmeen kariyumundu” (There is mackerel fry and pearlspot fry, also prawns curry made with Malabar tamarind). Generations have passed, but the love for the song hasn’t ceased; it was remixed and re-released years later. Similarly, “Pennale pennale, karimeen kannale kannale” (Girl, oh girl with the Karimeen-like eyes) uses the fish as a simile for the beautiful eyes of a woman—one of many such cultural references.

The fish’s significance is reflected in historical records as well. Texts and documents from the colonial period frequently mention it. James Hornell, former Director of Fisheries, and N.P. Panikkar, Inspector of Fisheries in Travancore, extensively studied and wrote about the Pearlspot in the Madras Fisheries Bulletin, which was released in 1921.

Food historian Deepa G explains that scholars of that era often referred to the Karimeen as a common man’s fish in South India and Sri Lanka. “With the emergence of new research on diet, nutrition, and food consumption, the fish gained significant importance, eventually becoming Kerala’s signature fish,” she says. It was already a staple for communities living near mangroves, particularly those who relied on fishing for their livelihood. The Madras Aquarium Report of 1921 also lists the Karimeen as a regional food source.

A perennial delicacy

Whether you're from Kerala or not, if you've tasted Karimeen, chances are you have a story to tell. For some, it’s the challenge of navigating its delicate bones, while for others, it’s a memory tied to the vibrant toddy shops of Kerala, where spicy Karimeen preparations are best enjoyed with a glass of freshly tapped palm wine. This fish is deeply woven into Kerala’s culinary fabric in more ways than one. In Kuttanad, there’s even a saying that a prospective groom must prove his worth by skillfully eating a Karimeen—leaving nothing but the bones behind.

But what gives the Karimeen its unique taste—the faint undertone of clay, a hint of earthiness, and a mild sweetness? According to marine biologist KK Vijayan, who served as the director of the Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (CIBA) for 15 years, it’s the backwater ecosystem. “Karimeen’s flavour profile largely depends on the water it inhabits. The backwater ecosystem, as we know, is ideal for it to thrive. The confluence of freshwater and seawater creates stress on the fish, forcing it to adapt. This stress triggers the production of antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which contribute to Karimeen’s distinctive flavour,” he explains.

The confluence of freshwater and seawater creates stress on the fish, forcing it to adapt. This stress triggers the production of antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which contribute to Karimeen’s distinctive flavour.

Interestingly, in an attempt to discover the best-tasting Karimeen, a 2024 study by the Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS) analysed both taste and nutritional differences in the fish from six locations. The study confirmed that the tastiest Karimeen comes from Kanjiracode in Kollam and Azheedoke in the Thrissur district. These findings are expected to bolster efforts to secure a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for Kanjiracode Karimeen.

In troubled waters

Despite its cultural and economic importance, the fish faces existential threats. According to estimates by CIBA, as of 2020, Kerala produces around 2,000 tonnes of Pearlspot annually through farming, against a demand of 10,000 tonnes. “Wild stocks of fish, including Karimeen, have declined drastically. Over the past 10-15 years, marine catch has stagnated despite advancements in fishing technology,” says Vijayan. While specific data on the volume of Karimeen brought in from Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka to Kerala is not readily available, one thing is certain: without this exchange, the state cannot address the gap between the production and the high consumer demand for this fish.

It's true that the size has come down. However, that is because of continuous harvesting. We are not allowing the fish to grow to its full size.

The availability in the wild has been declining over the years due to a combination of environmental challenges, overfishing, and habitat degradation. The biological characteristics of the species, including low fecundity (number of eggs laid in a spawning season) and smaller clutch size (number of eggs laid in a single nesting attempt), are other factors. The reclamation of water bodies for urbanisation and other uses has further contributed to the Karimeen’s dwindling numbers.

Bhat warns that fish can be sensitive to certain pollutants, which means that a sudden change in water quality is bound to affect them. “The Pearlspot may be a hardy fish when compared to many others, but even it may not be immune to certain external factors. Our own bodies struggle to adjust to temperature changes that accompany each passing year and the impact on our physiology. It’s similar for the fish as well,” says Bhat.

Studies in the last few years echo these concerns, noting a drastic reduction in catch. One particular study that looked at data generated from the fishing grounds of the Vembanad Lake in 2012-13 found that even from this one source, the annual landings seem to have gone down to 135.28 tonnes from an earlier record of 1252 tonnes in 1969—and this was over 10 years ago. More recently, total inland production of Karimeen fell from 4644 tonnes in 2006-07 to 4194 tonnes in 2018-19.

In the Vembanad Lake study, local fishermen revealed that the average size of the fish in their catch has reduced substantially in the last decade. A little further away, in the Ashtamudi lake in Kollam district, the length of the Karimeen has reduced by 10 cm, according to a census conducted in 2022 by the aquatic biology department of Kerala University and Fisheries Department, jointly.

“It's true that the size has come down. However, that is because of continuous harvesting. We are not allowing the fish to grow to its full size. Within a year of hatching, they are harvested. If we wait for 2-3 years, the size will substantially increase,” says Bhat.

Vanishing spawning grounds

Aside from environmental stress, the population is also strained by particular fishing activities. Niyas, a fisherman from the Ernakulam district, explains that there are some who specifically target the Karimeen while it spawns. “A unique behaviour exhibited by the Karimeen is that it makes small holes in the riverbed to protect its eggs and fry, or the newly hatched fish. Once the hole is made, the male and female parents won’t abandon the area. A section of fishermen take advantage of this, walking over the river bed till they feel the holes with their feet and catch the fish with their hands. Sometimes they use a ring-like structure and place it over the hole to trap the fish.” With parent fish being targeted in this manner, the impact on the overall population is inevitable.

Dr. Vikas PA, a subject matter expert at Krishi Vigyan Kendra, explains: “It’s in the fish’s nature to stay around these holes and fan water over the eggs to keep them oxygenated while protecting them from predators. But this makes it easier for people to catch them. Exploiting this method can cause a decline in the overall numbers of the fish.”

People who overfish and exhaust the fish in their locality turn to other areas at night to fish for Karimeen.

No less problematic is the illegal trading of the fingerlings, most of which don’t even survive the exchange. Most fisherfolk are against catching fingerlings—the tiny, weeks-old young of the fish. This directly cuts into the number of young fish that can grow and reproduce. “Even if I accidentally catch them, I let them go. But some people keep and sell them for Rs. 10 or Rs. 20 a piece,” says Arun. People who overfish and exhaust the fish in their locality turn to other areas at night to fish for Karimeen.

The destruction of mangroves in the state has been tough on the species. In the last three decades, over 90% of mangroves in Kerala have been destroyed; from a vast 700 sq. km in the 1980s, the mangrove cover is down to a measly 17.82 sq. km, as per a 2020 study. These marshy regions serve as critical breeding grounds for the fish, and their drastic disappearance has reduced safe spaces for laying eggs. “Mangrove roots, once ideal for hatchlings, have been replaced by less suitable sludge, where young fish cannot survive. Changing rain patterns, particularly summer rains, and fluctuating salinity levels during June and July further disrupt the fish’s habitat,” says Dr Vikas.

Climate change and fluctuating water quality pose additional threats. “Our backwaters are in a poor condition. Many have become shallow due to siltation and the lack of tidal activity. Human activity—particularly urbanisation—has significantly degraded these ecosystems. Rainwater washes pollutants into rivers, reducing oxygen levels and causing fish mortality. Climate change has also altered water temperatures and breeding behaviors,” says Vijayan.

Bhat elaborates on the severity of the situation, drawing attention to the disastrous consequences of industrial waste. “The Periyar River, which feeds into the backwaters, is lined with industries that discharge untreated waste into the water. Over the past 20–30 years, the Kochi backwaters have shrunk considerably due to encroachment, disrupting the natural flow of freshwater and further degrading water quality.”

The great imposter

An unexpected challenge to the Karimeen’s survival is from the Tilapia, a highly fecund and easily bred fish that is outdoing it. Invasive Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) variants, known for their resilience, adaptability, and rapid growth, have become a preferred choice for farmers.

This hardy and cost-effective alternative actually threatens the Karimeen’s prospects in Kerala’s aquaculture. In fact, as of 2022, the total Tilapia production in the country was estimated to be about 70,000 tonnes; of this, 30,000 tonnes came from aquaculture alone. This large proliferation comes from the fact that even though Tilapia was only introduced to Indian waters decades ago, the fish has naturalised quickly, adapting and breeding in large numbers. The catch percentage of the Tilapia increased from 6.7% to 85.9% in the decade from 2008 to 2018. In the Kozhikode district of Kerala, Tilapia is now the most cultivated fish.

Tilapia is sometimes mistaken for Karimeen—both fish, after all, belong to the same Cichlidae family. Medium-sized Tilapia (300g–400g) can closely resemble Karimeen, and some restaurants have even substituted Tilapia for Karimeen. Vikas notes, “Some unscrupulous sellers may try to pass off Tilapia as Karimeen, especially to those unfamiliar with the size and taste differences.”

Medium-sized Tilapia (300g–400g) can closely resemble Karimeen, and some restaurants have even substituted Tilapia for Karimeen.

But that’s not all: the Tilapia is an invasive species, which are generally considered harmful to the natural habit into which they’re introduced. They can also feed on natural resources as well as the young and eggs of native species of a habitat, like the Karimeen.

Battle for survival

Given these challenges, large-scale breeding remains uncommon in Kerala. “While some individuals collect eggs from breeding grounds and transfer them to smaller water bodies, systematic, large-scale breeding is not widely practiced,” notes Bhat.

Driven by the uncertainties of fishing, Karimeen farming in Kerala can be best described as an ‘emerging interest’: the fish are often bred in ponds, or cages in open waters.

“Water quality is vital—if it deteriorates or the acidity changes, fish can die. Oxygen levels must remain stable, but we rely on river water, which is sometimes polluted.

The controlled culturing of Karimeen requires a multifaceted approach. Hatcheries can regulate breeding and ensure fish are reared in controlled conditions, while the desilting of canals, restoration of tidal flow, and reintroduction of hatchery-bred juveniles into the wild could help replenish stocks.

“Aquaculture serves both conservation and commercial interests. It reduces overfishing in the wild, even if broodstock is sourced from nature,” says Bhat. He is referring to the pool of parent fish that serve as the genetic foundation to breed further fish. However, he warns of the environmental risks of large-scale commercial farming, emphasising the need for sustainable practices.

“Environmental, economic, and ecological consequences are inevitable—water pollution, disease transmission, and ecosystem degradation, for instance. However, these risks arise primarily when aquaculture is practiced on a large scale, which is not yet the case in Kerala. But as we expand, it is crucial to adopt sustainable practices after carefully weighing the pros and cons,” says Bhat.

Raising them right

Shibu, a hatchery owner in Puthukkad, ventured into Karimeen farming in 2018 after attending a Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) course. He now produces over 1.5 lakh Karimeen fry annually, but his success is strongly dependent on water quality and environmental factors.

“Preparing the pond is crucial. We need to eliminate weed fish, balance the water’s pH, and use lime to condition it. Only after the pond is ready do we introduce the brood fish. It takes about 45 days to get the seed, which is then moved to a hapa and fed thrice daily,” Shibu explains. A hapa is a rectangular net enclosure placed over waterbodies to hold fish.

Farmers purchase these seeds to rear fish, but challenges persist. “Water quality is vital—if it deteriorates or the acidity changes, fish can die. Oxygen levels must remain stable, but we rely on river water, which is sometimes polluted. We also deal with predators like cormorants and otters,” he says.

Marketing is another major hurdle. “We have the seed stock but struggle to sell it. Social media and newspaper ads help, but the support of state fisheries and centralised branding could make a big difference,” he says. With Kerala’s Karimeen demand still heavily reliant on wild catches, Shibu believes more people need to take up farming to bridge the gap sustainably.

Scaling up: innovation and infrastructure

To make Karimeen-centric aquaculture viable, Kerala needs comprehensive programs for seed production, feed development, and farming technology. Small-scale backyard hatcheries, supported by the government, could engage communities living near backwaters, suggests Vijayan.

Despite experimental breeding efforts by institutions like the Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (CIBA), the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), and the Kerala Fisheries College, large-scale commercial hatcheries have yet to materialise. “The larvae produced in these hatcheries are too few to support widespread aquaculture. For aquaculture to succeed, we need commercial hatcheries capable of producing seeds in significant quantities,” adds Bhat.

On a positive note, KUFOS recently proposed a genome editing mission to enhance Pearlspot production. Currently, fish farmers in Kerala face challenges such as sourcing broodstock from the wild, breeding them in uncontrolled environments, and releasing fingerlings into aquaculture ponds, only to see the fish reach a modest weight of 300–400 gm in a year. This pales in comparison to the maximum reported weight of Karimeen caught from the Vembanad Lake, which stands at 1.2 kg.

The KUFOS’ genome editing mission aims at revolutionising aquaculture, much like the GIFT initiative did decades ago. By targeting the genetic factors that inhibit faster growth rates, the project could enhance breeding and seed production of the Pearlspot. Achieving higher body weights at an accelerated rate would significantly benefit farmers, as the Karimeen commands a premium in the market compared to Tilapia.

The way forward

To farm the Karimeen sustainably, Kerala needs to address several technical, economic and social challenges. Farmers must adopt scientific practices to make ventures profitable and ecologically sound. “Economic viability is a must. Farmers should receive reasonable prices for their produce,” says Bhat.

But the list of measures doesn’t end there; management practices are crucial, too. “Proper pond preparation, stocking, feeding, water quality maintenance, disease prevention, and humane harvesting are critical,” he adds.

What Kerala—and its star fish—needs is a mission program.

Urgent steps must be taken to adopt better aquaculture practices. “The Pearlspot grows slowly—it can take up to a year to reach maturity. For farming to be profitable, we need technology that shortens this period to six months,” says Vijayan. Mixed farming, where the Karimeen is reared with species like Flathead Grey Mullet (Thirutha), Milk Fish (Poomeen), or shrimp, could help farmers earn multiple incomes. “Composite farming may be an old concept, but it is still highly relevant,” says Vijayan.

While the Karimeen has unique traits like parenting—the parent fish’s effort to protect the young after spawning—breeding control remains a challenge. Pairwise breeding is essential to maintain quality seed, but current practices often lead to inbreeding. Generally, this could affect the fecundity, growth rate and survival of the young; it could even encourage illness and deformity. “The Karimeen produces an average of 1,000 eggs across one breeding season—far fewer than tiger shrimp, which can lay over a million eggs. But Kerala lacks commercial hatcheries with controlled seed production. We need hatcheries where male and female fish are kept under controlled conditions to breed, with larvae reared and sold to farmers,” Vijayan emphasises.

What Kerala—and its star fish—needs is a mission program. There are certainly standalone schemes, like a boost from the Multispecies Aquaculture Complex (MAC) for Karimeen farming in the Kochi complex, or broader programmes like the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana’ (PMMSY) that aim at enhancing inland fisheries at large. The state has resources and manpower, but they aren’t connected by a unified vision. CIBA has successfully developed pair breeding technology for the Pearlspot, enabling cost-effective modular hatcheries to produce quality seeds in required quantities and timelines. While the institution is ready to offer scientific and technological support, the authorities have to create a roadmap to improve the sector. It requires a comprehensive plan, financial assistance, and coordinated efforts between the scientific community and the government.

A collaborative approach that integrates scientific innovation, government support, and community participation is the need of the hour. Empowering farmers with technology and promoting ethical practices will not only boost the local economy but also preserve ecological balance. Such efforts will ensure that this cherished species continues to thrive for generations to come, while also enabling people like Arun to follow in his father’s footsteps and once again rely on the Karimeen for their livelihood.

Edited by Binu Karunakaran, Anushka Mukherjee, and Neerja Deodhar

Produced by Nevin Thomas and Neerja Deodhar

Cover art by Prabhakaran S

All photos by Joseph Rahul

Also read:

The perilous future of Kashmir’s once-abundant trout

Omega-3 fatty acids: The hidden costs of ‘health’ to our seas

Explore other topics

References

.avif)