Kerala’s action against the sale of antibiotics without appropriate prescriptions has now inspired Telangana

In November 2024, Kerala hit a remarkably unique milestone by logging a reduction in antibiotic sales to the tune of over Rs. 1000 crores. Over the years, the state has strengthened its Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) intervention through a multi-pronged approach, slashing the consumption of antibiotics by 20-30%, according to a statement by Health Minister Veena George.

A significant decision that contributed to this result was taken three years ago, when the state government resolved to suspend or cancel licences of pharmacies selling antibiotics to customers without a doctor’s prescription. This year, the crackdown gained strength: in June, the licences of 450 pharmacies were suspended and five were cancelled, for not adhering to the given direction.

Making pharmacies accountable

The impact of this drive is wider awareness that is prompting people to act. “After the COVID-19 pandemic, people would buy antibiotics using old prescriptions if any symptoms recurred. But now, people have now become aware that they should not be consumed without a doctor’s prescription. The awareness against unchecked antibiotic use has spread to a vast majority of people, though I won’t say it has reached everyone,” reveals a pharmacy owner whose establishment is based in Pettah, Ernakulam. He adds that the purchase of medicines using outdated prescriptions has been considerably reduced now.

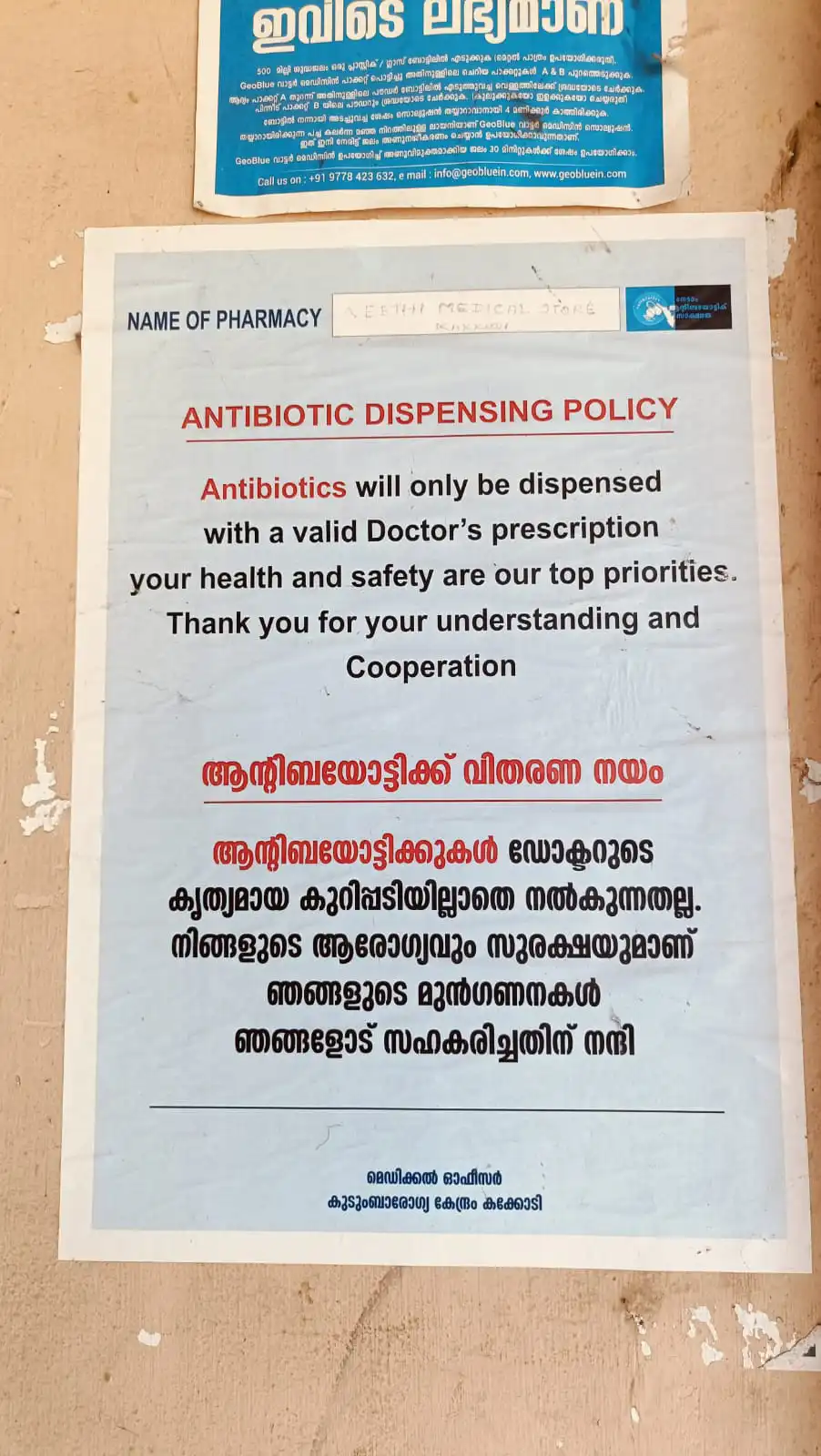

Every pharmacy must clearly display a poster that reads ‘antibiotics not sold without a doctor's prescription’; strict consequences await those who don’t.

There are more than 30,000 retail and wholesale medical shops in Kerala, which are reportedly the focus of ongoing awareness classes for pharmacists. “Medical shops were the core of the campaign, making it their own and putting up the posters on their walls, perhaps because the state has a high literacy rate. People needed no explanation but the posters,” says Dr. Sujith Kumar K, Kerala Drugs Controller. He is referring to the mandate that every pharmacy must clearly display a poster that reads ‘antibiotics not sold without a doctor's prescription’; strict consequences await those who don’t.

Dr. Kumar adds that the Drugs Control Department is working to launch the Sentinel Pharmacy framework to provide accreditations to pharmacies that follow key performance indicators. “These will be model pharmacies, and they will be provided colour codes to be identified as such.” In 2024, the state government announced that this accreditation would enable pharmacies to play a part in disease surveillance and tracking outbreaks by reporting drug purchases and unusual patterns in usage.

AN Mohanan, the President of the All Kerala Chemists and Druggists Association State (AKCDA), underscored that the AMR drive had indeed made a dent. “By and large, medical shops don’t sell antibiotics without a prescription now. Kerala is a progressive state, and the medical shop owners are convinced about the consequences of unchecked sales,” he says.

‘Monitored like narcotics’

Another pharmacy-centric action has been the introduction of surprise raids in retail chemist shops by the Kerala Drug Control Department. In fact, even the general public has the power to make a change: the state provides a toll-free number where you can lodge complaints if you see a medical shop selling antibiotics without a prescription. These raids fall under Operation AMRITH (Antimicrobial Resistance Intervention for Total Health), a key project that has enabled several other initiatives since its launch in January 2024.

“The sale of antibiotics now is like that of narcotics, not available without a prescription, and monitored during raids by inspectors of the department. Now, there are regular raids under Operation AMRITH,” the Kerala Drugs Controller says.

Also read: Add crisis to cart: Why instant delivery and antibiotics don't mix

A long road lies ahead

Patients are now more easily convinced when advised to avoid using antibiotics, says ENT specialist Dr. Divya PK, who is the Medical Officer of the Primary Health Centre (PHC) at Koodaranji, Kozhikode. “The use of antibiotics at the outpatient wing has reduced, and patients can’t buy from pharmacies without a prescription. However, constant effort is needed to keep motivating people; the pace should not slow down when a new program is launched,” she adds. Dr Divya was instrumental in transforming the Kakkodi Family Health Centre (FHC) in Kozhikode into an antibiotic-smart hospital. To do this, the Health Centre successfully followed and implemented all of the 10 guidelines issued by the state on curbing the overuse of antibiotics, becoming the nation’s first such hospital.

We follow the exact prescription, and medicine is sold again only if the doctor has suggested a repeat purchase. We are aware of the consequences of unchecked use of all kinds of medicines, not solely of antibiotics.

Despite the government’s proactive stance, a major challenge is that buying only prescribed antibiotics has not gone down well with non-Keralites residing in the state. “They show us prescriptions sent to them via WhatsApp, and the doctors (from their home states) encourage us to sell medication without a physical prescription,” reveals the Ernakulam pharmacy owner quoted earlier. Worse yet, buyers ask for two or three tablets, which chemists like him don’t encourage. “We follow the exact prescription, and medicine is sold again only if the doctor has suggested a repeat purchase. We are aware of the consequences of unchecked use of all kinds of medicines, not solely of antibiotics,” he asserts.

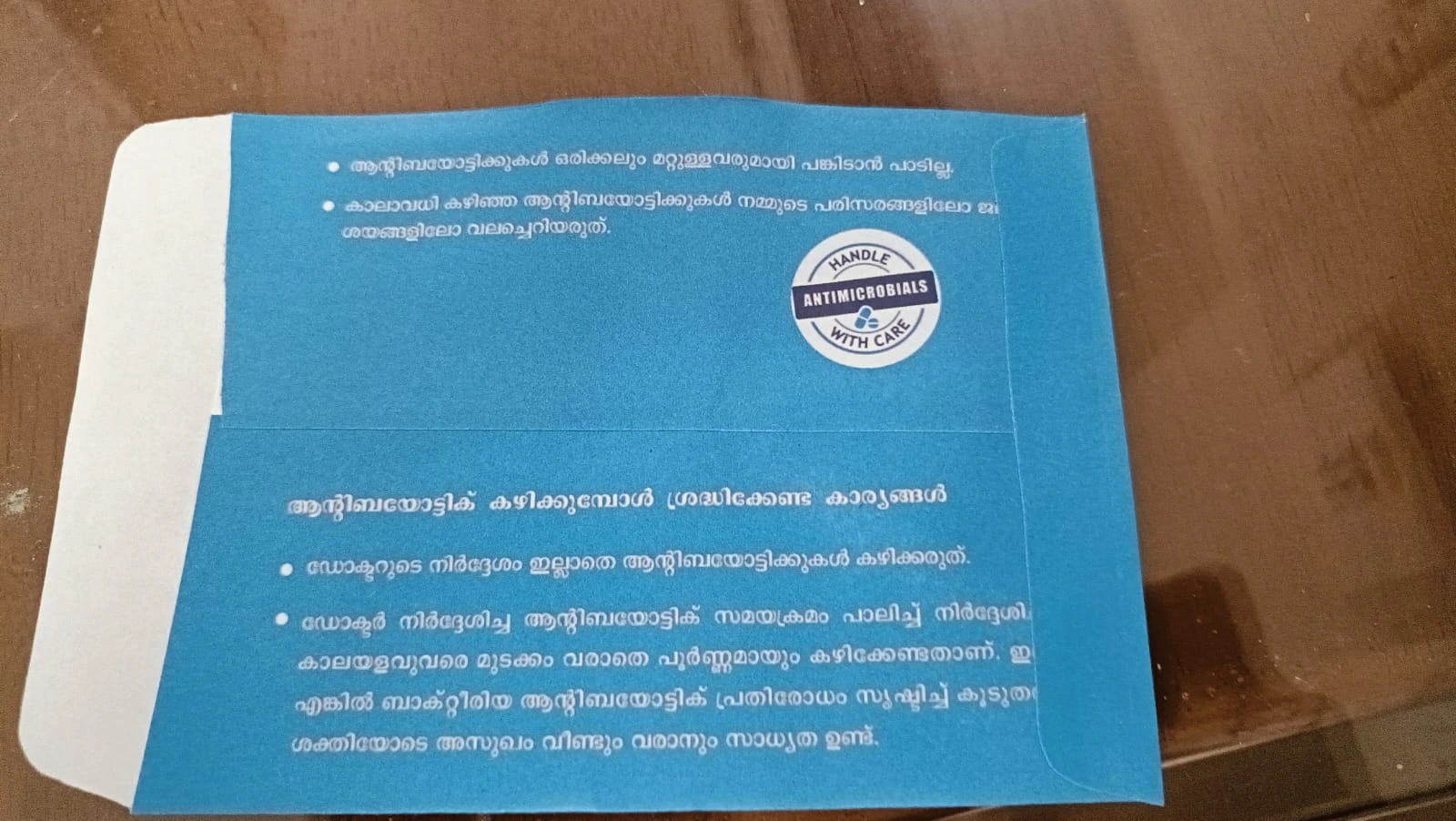

AN Mohanan addresses the government’s direction to sell antibiotics in a blue cover. The mandate dictates that all antibiotics be sold in a blue-coloured bag, so that they can be easily identified. This applies to all medical stores, pharmacies and hospitals. Mohanan specifies that this decision may not be practical because the blue bags aren’t provided by the government. “The Kerala government should hold meetings with us before coming up with regulations, taking us into confidence. Certain things, like selling antibiotics in a blue cover, cannot be made mandatory because of the practical difficulties involved,” he explains. There have been instances where pharmacy licenses have been suspended for selling two or three tablets without a prescription, he notes. “However, when we speak against the unchecked use of antibiotics in our forums, there is a positive impact,” he says.

The impact has carried over; following the suspension of Kerala’s pharmacies in June, the Telangana Drug Control Administration (DCA), too, conducted a state-wide crackdown on its pharmacies. Raids across 193 establishments revealed widespread non-compliance: shops selling antibiotics freely without prescriptions, sales in the absence of qualified pharmacists, and without a proper record of the medicines sold. The raids have spurred the DCA into action, which has indicated a zero-tolerance policy.

In fact, even the general public has the power to make a change: the state provides a toll-free number where you can lodge complaints if you see a medical shop selling antibiotics without a prescription.

Even in the strongest of Kerala’s districts, a major cause of worry is that awareness against antibiotic overuse stands at 40% which demands augmented actions, says Dr. Aravind R, who heads the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram. Standardised metrics are used to measure this progress, like those set by the World Health Organization (WHO). Dr. Aravind R adds: “The state has achieved the WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) criteria of the WHO. Another criterion set by the WHO is that 70% of antibiotic use should be from the Access category.”

Dr Aravind is referring to the category system set up by the WHO to monitor antibiotics, called the AWaRe classification. It has three groups: Access, which includes first-choice antibiotics because they treat common infections and have a lower resistance potential; Watch, a group of antibiotics with higher resistance potential that should only be used for specific, limited infections; and finally the Reserve group, which includes last-resort drugs that should only be used to treat infections caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria, and are highly likely to further AMR. “Yet another milestone to achieve is the WHO’s direction to reduce AMR-associated deaths by 10% by 2030,” he adds.

Also read: How drug-resistant tuberculosis is bringing life to a halt in India

Out with the old

It is not enough to merely address the accessibility of antibiotics that are newly purchased; the extent of antimicrobial resistance is also defined by the usage of old antibiotics. Leaving unused strips and bottles of these drugs around poses risks because consuming them beyond the stipulated period can lead to further illnesses and increased resistance. The AMR intervention in Kerala recognises this, and the state has put into motion–through early pilot projects–the Programme on Removal of Unused Drugs (PROUD). In recent years, it has renewed this programme to sharpen the scope. The programme now collaborates with the Haritha Karma Sena or the Green Task Force, which is made up almost entirely of women engaged in the state’s waste management drive. Trained members of this group conduct door-to-door collection of unused medicines, including antibiotics.

“The idea is to first make people aware, and then act. We collected 28 tonnes of unused drugs from commercial establishments and households under the Corporation and the Panchayat. The change will be big when this is implemented across the state,” Dr Kumar adds.

Also read: Sivaranjani Santosh’s fight to knock mislabelled ORS off the shelf

Additional inputs from Neerja Deodhar and Anushka Mukherjee

Edited by Neerja Deodhar and Anushka Mukherjee

Explore other topics

References