Dr Vanaja’s research turns the tide for paddy farmers

Vast stretches of green and golden paddy spikes sway in the cool breeze, creating a musical rhythm as you glide through the brackish waters of the naturally organic Kaipad (kayal padam) fields, fringed by mangroves. The fields are the lifeblood of coastal villages in Kannur, Kasargod, and Kozhikode, especially in Ezhome panchayat, Kannur, the hub of Malabar Kaipad cultivation.

Here, Dr Vanaja T, associate director of research at Kerala Agriculture University and head of the Regional Agriculture Research Station (RARS) in Pilicode, Kasargod has been working passionately to breed better varieties of paddy for farmers.

“I have hybridised traditional and international varieties in a more saline region than before, creating a high-yielding, saline- and flood-resistant variety with better nutritional value,” she said. Dr Vanaja’s dedication, combined with the farmers' needs, led to the development of five organic, saline-resistant hybrid varieties: Ezhome 1, 2, 3, 4, Jaiva (for non-saline fields), and Mithila, all the result of experiments started in 2000.

Indigenous methods

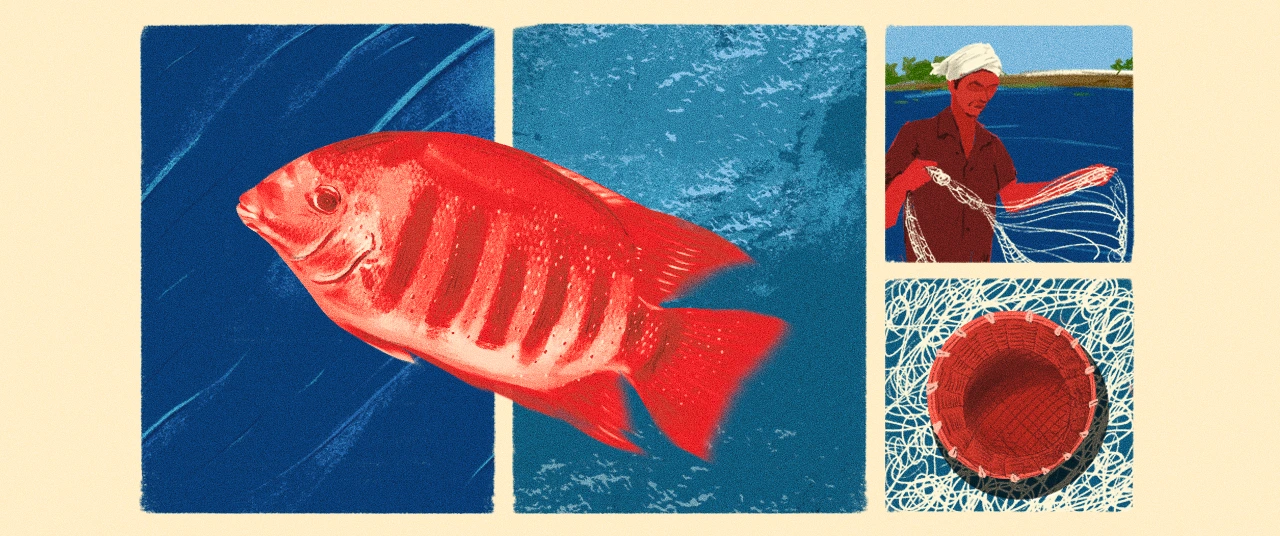

The rich biodiversity of the land is palpable. The unique calm is as soothing to the mind as the nutritious Kaipad rice is to the body, a connection evident in the villagers' health. “We eat only Kaipad rice in various forms, accompanied by organic vegetables, tubers, fruit, or fish from our farms. We grow paddy during the monsoon in saline-free water, from June to November, and fish after the harvest, from mid-November to April,” said agriculturist C Govindan Nambiar.

“We have always followed this unique indigenous farming method. The saline-resistant rice varieties are nurtured and nourished by the tidal flow. Before the monsoon sets in, we make mounds. After the rains remove the salinity, we sow the seeds in each mound. When it's time to replant, the men scatter the mounds in a specific way, and the women place the saplings in the right positions. We sow and reap in neck- or knee-deep water and marshy soil–a very laborious task. The beds are visible during low tide,” he said.

“We do not use fertilisers or pesticides. After the harvest, it’s time for fish. The sluice gates are closed, and the fish, shrimp, and crab seedlings that flow in from the sea feed on the paddy stubs and other organic matter. After harvesting the fish, they are often exported. The stubble waste, fish, and bird droppings, including those of migratory birds, fertilise the soil,” Nambiar explained.

“We did face issues, but thanks to Vanaja madam, most have been resolved,” he added.

Reviving Kaipad rice

Vanaja has been instrumental in reviving Kaipad rice cultivation and supporting small and marginal farmers through her research and initiatives. “When I started my career as an agriculture officer, I was appointed to the Pepper Research Institute, despite specialising in rice. On State Farmers' Day, the first day of the Malayalam month of Chingam in 2000, I was asked to give a talk to the farmers of Ezhome Panchayat as part of the celebrations. I spoke about various aspects of rice farming when Govindan Nambiar, representing the farmers, interrupted, saying my talk had nothing to offer them.”

Vanaja paused and asked about their concerns. The farmers struggled with low yields from the indigenous Kuthiru and Orkkayama varieties, lodging (where stalks fall to the ground), and the nuisance of awns during harvest.

We should salute the hands that secure food just as we salute the hands that defend the country.

Though she was at the Pepper Institute, she promised the farmers that she would support them, even if it meant conducting the research herself. When she presented the DPR, the university approved it because it was a demand from the farmers that no one had addressed.

New varieties

Vanaja began her experiment at home, hybridising traditional varieties in 200 pots. After much effort, she successfully developed a set of seeds. She leased Kaipad land from a farmer, turning the area into her lab. Vanaja involved the farmers to understand their needs and combine their knowledge with science. After many trials and evaluations based on various criteria, she developed Ezhome 1 and 2 in 2010, naming them after the village. That same year, the Malabar Kaipad Farmers' Society (MKFS) was established, focusing on the conservation, cultivation, consumption, and commercialisation of Kaipad rice. Ezhome 3 was developed in 2014, followed by Ezhome 4 in 2015.

The new varieties offer 60 to 80 percent higher yields than the traditional ones. They are lodging- and awn-free, tastier, and more nutritious.

During the harvest festival inauguration for Ezhome 3, the then agriculture minister was taken by canoe to cut the stalks. However, the canoe overturned, drenching the minister. Along with the local MLA, the minister waded knee-deep through the field to cut the sheaves, gaining firsthand experience of the farmers' struggles.

“The new varieties offer 60 to 80 percent higher yields than the traditional ones. They are lodging- and awn-free, tastier, and more nutritious,” said Vanaja. After years of effort, Kaipad rice received the Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2014.

“Ezhome 4 is high yielding and flood-resistant, and farmers want to grow more,” said Ezhome panchayat president P Govindan. “But labour shortages, high production costs, lack of mechanisation, and low prices prevent expansion. We need to attract younger generations by boosting the food security army, offering monthly salaries, and introducing mechanisation.”

Challenges and opportunities

In 2019, the governmental agency Kaipad Area Development Society (KADS) was established, with Dr Vanaja as its director. It is the only agency of its kind in north Kerala. According to farmers, the northern districts are a neglected area. In 2020, the Malabar Kaipad Farmer Producer Company (MKFPO) was registered.

To support the farmers and encourage self-entrepreneurship, a Food Security Army (FSA) was formed on a profit-sharing basis. “We should salute the hands that secure food just as we salute the hands that defend the country,” said Vanaja.

The consumption of Kaipad rice has been significantly promoted through awareness initiatives in 52 self-governing bodies across three districts. Kaipad products have been introduced in markets throughout Kerala. The importance of healthy eating is conveyed through a food park set up near the Thavam rail overbridge in Cherukunnu panchayat. Slogans highlighting the need for and benefits of nutritious, organic food adorn the walls. The area houses a production unit and an outlet where Kaipad rice, rice flakes, ‘puttu’, ‘pathiri’, idiyappam, prawn chutney powders, sweetened rice balls, and health mixes for all ages, as well as ‘payasam’, are sold. Most products are also available online.

In the food park, rice gruel made from Kaipad rice is served in earthen pots, accompanied by legumes, ember-roasted ‘papad’, pickles, vegetables, and tonic chutney made from Indian pennywort (muthil), water hyssop (brahmi), or other medicinal herbs. It costs Rs 50. Fish and eggs are also served at an additional charge. “We take turns cooking, making value-added products, packing, and selling in our outlets, catering to tourists who generally book in advance. The gruel at the park is a hit, and our products are in demand,” said Soumya of FSA.

Farm tourism is also being promoted, offering visitors the opportunity to participate in the cultivation process, enjoy canoe rides, relish healthy food, and bask in the beauty of nature.

.avif)

Kaipad rice and its value-added products were first exported to the UAE in 2019 and are now reaching other countries. The demand exceeds supply. “Today, people have begun to approach us for rice and value-added products, but we don’t have enough paddy to fulfill large orders. Last year, we harvested only 9 tonnes, compared to 15,000 tonnes the year before,” said MKFPC secretary Nidhina Das.

MKFS secretary M K Sukumaran supports her claims. “We have new seed varieties, but cultivation has decreased by 50 percent compared to a few years ago because it has become risky. When farmers are unable to cultivate for a year, mangroves intrude, and it’s illegal to clear them. Moreover, climate change, saline intrusion, and threats from pigs, tortoises, and birds present significant hurdles. We can increase cultivation if the government helps us address these issues and raises our subsidy. The government’s promises have yet to reach us,” he said.

“Steps are being taken to address the challenges facing Kaipad and make cultivation profitable to attract more farmers and youth. The government has begun marketing organic rice varieties and value-added products from across the state online under the brand ‘Kerala Agro’ through the Krishi Bhavan to secure better returns for farmers,” said agriculture minister P Prasad.

In 2020, MKFS received the Plant Genome Saviour Community Award from Indian president Droupadi Murmu during the Global Symposium for Farmers’ Rights in September 2023, in New Delhi. The Kaipad stall was one of the few visited by the president.

Meanwhile, Vanaja is focusing on the Research and Development Centre being set up on a hillock where viewers can see the Kaipad fields. The lower floor will house the food park and outlets, while the upper floor will contain the lab and other facilities. “I had to depend on toilets in farmers' houses. Better infrastructure will help attract more researchers and contribute more to Kaipad development,” she said.

{{quiz}}

Explore other topics

References

- The Hindu. (2013, August 7). GI tag for Kaipad rice to boost cultivation. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/gi-tag-for-kaipad-rice-to-boost-cultivation/article4989083.ece

- Kaipad Farmers. News. https://www.kaipadfarmers.org/news

.avif)

.png)