A farm is more than a patch of land; she is a symphony whose melody may not be apparent to those who only see her functionally

Editor’s note: To know Rama Ranee is to learn about the power of regenerative practices. The yoga therapist, author and biodynamic farmer spent three decades restoring land in Karnataka, envisioning it as a forest farm in harmony with nature. In ‘The Anemane Dispatch’, a monthly column, she shares tales from the fields, reflections on the realities of farming in an unusual terrain, and stories about local ecology gathered through observation, bird watching—and being.

The first monsoon showers dampened the earth, and we took in the enchanting fragrance of plant oils and streptomyces—petrichor and hope (geosmin, a byproduct of the metabolism of the streptomyces bacteria—an indicator of soil health—adds the earthy note to this bouquet of aromas). Raised planting beds were ready with freshly sown seeds. It was like waiting for the curtain to rise on a grand opening, as this was during the early years of biodynamic farming at Anemane. When the mushrooms emerged and mycelium wove across the beds, they brought with them elation—a validation of our efforts to infuse life into starving soil.

Our tryst with the land began in the 1990s. We were faced with the challenge of regenerating soil that had lived as a scrub forest (a thorny forest home to spiny trees, common to the Deccan), converted into arable land, ravaged by granite quarrying and conventional agriculture. It was not merely the physical scars; it was the irrevocable changes to the chemistry and soul—the life spring.

Sixty years ago, burning down bamboo thickets and vegetation did indeed enrich the soil with wood-ash, releasing nutrients like potassium, phosphorus, and calcium, which boosted food production. It was inevitable that the initial supply of nutrients would deplete, increasing soil alkalinity. With denudation and the loss of green cover, there was a decline in organic matter. The unregulated use of chemical fertilisers further degraded the soil. High inputs of urea increased soil acidity, destroying soil biota. Whether it is high levels of alkalinity or acidity, the soil suffers from a reduced capacity to hold water, support life and crops.

Add to this a generous sprinkling of granite dust from the quarries, and what we had was a grey, ashy medium. Granite quarrying only exacerbated the troubles caused by the loss of green cover, and the resultant dust could potentially contaminate groundwater and affect human health.

While the early farmers in Kasaraguppe, where Anemane is located, managed well with inputs of composted dung, tank bed soil (inputs of composted dung and soil from a desilted tank bed rich in organic matter and bio-mass), their sons had to rely more on ‘government gobbara’ (chemical fertilisers) and Green Revolution methods that demanded increasing quantities of chemical inputs.

The mushrooms in our raised plant beds were the opening chords of a symphony—one that came together note by note, quietly, over a decade. They were indicators of the positive change that had we hoped for. Mycelium generally thrive in a more neutral pH soil and in organic matter which they convert into humus, improving the quality of the soil; higher soil organic matter (SOM) meant better porosity. Livingness was taking hold.

Preventing soil erosion

Anemane Farm sits atop a rocky knoll in the Bannerghatta National Park, facing the Suvarnamukhi Hill, with valleys on either side. The undulating land slopes sharply to the east and west, making it susceptible to erosion from wind and rain. The soil depth varies from barely an inch on the hilltop and east, to a few metres in pockets, with a maximum of about six meters in the valley to the east. Measures to prevent erosion were our primary concern.

Tall trees, mainly teak and silver oak, were planted in the interspaces of fields as wind breaks. Close planting made an effective barrier, which was later gradually thinned as the canopies grew wider. While the land had been terraced, there was no vegetation to prevent soil from being washed down the slopes to the west. Contour bunding and planting wind breaks, chiefly local varieties of bamboo and agave like cacti, reduced the impact. The bamboo soon grew into thickets, which made for wonderful homes for babblers, and spur fowls. The cacti seeds, an offering from a friend, were planted much to the disapproval of senior staff member Narasappa, who feared that we were providing shelter to Russell’s vipers. Narasappa was right, but since the cacti were meant to secure the peripheries, no harm was done.

A network of shallow trenches surrounded the fields feeding into larger ones. The bunds were lined with aloe vera and vetiver. Aloe vera, with its shallow and fibrous root system, binds the soil and retains soil moisture, while the leaves store water. Vetiver’s own deep root system conserves soil and promotes infiltration of water. Both are drought-resistant. Fodder grasses, too, contributed to erosion control, lining seepage pits and peripheral trenches.

Trenches were crucial for garnering surface runoff. They served several purposes: top soil carried by the runoff settled at the base as did the water, percolating and gradually recharging the ground water. Leaf litter settled at the bottom turned into a fine compost. The effectiveness of these measures became apparent during periods of drought.

Also read: Farming under the elephant’s nose: Lessons in crop choices

Managing water

At the deepest point of the valley, which adjoins the forest, there is an open well. It was inspired by a legendary British legacy project that watered vast vineyards and orchards, as well as a water-powered flour mill at Doresanipalya, in south Bengaluru. It simply disappeared after the 1980s, buried in the concrete jungle. Ours was 25 feet in depth and width, a far cry from the 50-feet marvel, as the space and soil type did not permit such extravagance, or did we have a perennial water source. Skilled well-diggers—traditional craftsmen called ‘Mannu Vaddar’ from Punganur, Chittoor—were commissioned. It was lined with hand-dressed stones hewn from the nearly-deserted quarry, perhaps the last project that Perumalappa, the local stone cutter, undertook. The joinery is a work of art!

There was no natural spring to be found. Recharged by ground water from an old pond (Chennammana kunte) upstream, it has a capacity of 2.5 lakh liters, enough to irrigate 2 acres. Incidentally, this transformed the quarry into a deep bowl for harvesting rain water.

.jpg)

Rain-fed dry land is best served by tanks natural or manmade, a lesson to be learned from Kempegowda, the founder of Bengaluru. Historically, tanks meticulously designed and positioned were a part of the city’s primary source, an element of a larger interconnected water system linked to its lakes and rivers, serving various purposes. Stone-lined step tanks or kalyanis are still in evidence in temples. It was logical to design our own cascading chain of tanks to harvest rain water.

A shallow check dam was constructed at an elevated spot where a monsoon-fed stream ran down from the Suvarnamukhi Hll into our land and piped into the abandoned quarry which transformed into a lifeline, with a capacity of about 8 lakh litres—enough to meet our requirement for 8 to 9 months. Further downstream, smaller quarried hollows were bunded and leakages plugged to serve as rock pools.

Pot-drip irrigation, a traditional method using terracotta pots, ensured a weekly supply of 25 to 30 litres per fruit tree—a mix of lemons, pomegranates, and mangoes. This was a method we imbibed from an NGO in a cyclone-prone, water-scarce region in Andhra Pradesh. It was very effective until elephants made a hobby out of smashing the pots!

Also watch: She turned a barren wasteland into a forest farm in Bengaluru

Soil enrichment

The processes of building soil organic matter and washing chemical residues went together. For seven years, mulch crops like legumes (black and green gram) and leaf litter were integrated into the soil. During this period, locals grazed their goats, fertilising the land. Farmyard manure of goat dung initially sustained the land until Gange and Gauri, our first pair of cows of the Hallikar breed, arrived. Their presence ushered in momentous changes! They were prolific breeders, too. Soon we had Lakshmaiah, a mustachioed man of courage and grit, strong enough to encounter leopards, grazing 10 heads of cattle on the hill.

The absence of any green cover impelled us to plant fast-growing trees. Apart from indigenous varieties like Honge (Pongamia pinnata), Neem (Azadirachta indica), and Maha-neem (Melia dubia), legumes like Senna spectabilis, nitrogen-fixing trees like Agase (Sesbania grandiflora), Gobbarada mara (Gliricidia sepium), and Subabul (Leucaena leucocephala) were grown selectively for green cover, compost, and fodder for cattle. They were useful in regenerating denuded areas. However, proliferation is a threat, and periodic felling and clearing is necessary to maintain a balance. The lopped wood is used to fill up rocky depressions to build up soil organic matter.

Cow dung and urine are the main inputs for enrichment of the soil. Biodynamic compost augments its potential. Cow Pat Pit (CPP), made mainly from cow-dung, is a rich fertiliser particularly beneficial for root growth. Vermicompost in open pits provides a balanced medium for vegetables and potted plants.

Soon we had Lakshmaiah, a mustachioed man of courage and grit, strong enough to encounter leopards, grazing 10 heads of cattle on the hill.

Biodynamic agriculture, developed by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner and based on the wisdom of ancient agricultural practices, offers a unique perspective by highlighting the influence of cosmic bodies and the Earth on nutrient cycles essential for vitality and growth. The farm ecosystem is envisaged as a self-sustaining living being. Nourishing the soil through composting, crop rotation, and other natural methods revitalises the plants, farm animals, humans and indeed, the living environment, enriching biodiversity.

Biodynamic mixed leaf compost combines nitrogenous and carbon-rich materials like green leaves, cow dung and dry leaves in the right proportion, inoculated with microdoses of biodynamic preparations. Decomposed through fermentation, sanitised by the actinomycetes bacteria, and further digested by earthworms, it is ideal for most fruits and vegetables. A host of liquid manures and preparations are made and applied in sync with the Earth and cosmic rhythms. Traditional agriculture offers a range of natural growth promoters, manures, disease- and pest-management measures like Jeevamrutham and Panchagavya which we incorporate in our farming methods.

Re-wilding

The boundaries are protected from grazing and clearing, facilitating the regeneration of indigenous flora and habitats. Whenever planting was a necessity, local species were preferred. Wild shrubs and bushes are allowed to grow as hedges in the interspaces of fields, functioning as screens to guard the crops from the prying eyes of peacocks and elephants, integrating them into the farm design. Plants of ethno-botanical importance are conserved.

{{marquee}}

On the path to recovery

Biodiversity: Stumbling upon a lone Pink Nodding orchid (Geodorum densiflorum) in a rocky patch for the first time was a revelation. Months later, whole clusters were discovered on a moist, leaf-littered slope keeping company with Dead Man’s Fingers (Xylaria polymorpha) under a dense canopy, where it continues to thrive. This terrestrial orchid does occur in the forests of Bannerghatta, but its abundance could imply a revitalised ecosystem—the transition from a disturbed landscape to a more stable, moist deciduous and evergreen type of habitat. The orchid’s symbiotic relationship with endophytic and mycorrhizal fungi indicates their presence, which is possible only in a healthy and balanced ecosystem. In-situ conservation gave them a reprieve from over-exploitation and threat due to habitat loss.

Species richness and abundance are clear signs of regeneration. Three decades ago, there were all of two trees—one Cluster Fig (Ficus Racemosa), and one White Bark Acacia (Vachellia leucophloea). Today, we have a diverse flora of 200 native species, of which 36 are trees. Among them are Jaalari (Shorea roxburghii) and Alale (Terminalia Chebula), climax species and mature guardians of a stable ecosystem. Climax species support high biodiversity and deliver crucial ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, and water regulation.

The mushrooms in our raised plant beds were the opening chords of a symphony—one that came together note by note, quietly, over a decade.

The land is blessed with weeds, or ‘children of Mother Earth’ as we call them. They constitute much of our 85 wild edibles, the rest being a mixed basket of shoots, berries, roots and mushrooms, valued for their healing and nourishing properties. A few plants of culinary and medicinal importance, such as Makali beru or Swallow root (Decalepis hamiltonii) are propagated. The Swallow root is significant as this is an endemic and endangered climbing shrub which grows naturally in rocky crevices and is threatened due to loss of habitat and over exploitation.

Rewilding has been instrumental in creating a bridge for larger mammals such as elephants and leopards, and habitats for birds (167 species have been recorded thus far), reptiles, small mammals, as well as a plethora of insects—ants, wasps, and beetles among them, a part of our extended family. Each play a role in sustaining the balance and overall health of the farm.

The Indian Screw tree (Helicteres isora), a deciduous forest species, grows in moist places. These shrubs began to appear with increasing moisture in the valley, possibly through the agency of nectar-loving birds like Purple-rumped Sunbirds of which it is a host. The birds, in turn, pollinate and disperse seeds. Positive relationships such as these augur well for regeneration.

When daily farm-walks began to reveal busy lady bird beetles, jumping spiders and parasitoid wasps clumping earth balls for their nests, and at times whisking away unwary caterpillars; ponds teeming with frogs, snakes and turtles; insect eating birds, and raptors as well, it was clear we had able partners in ‘pest’ management, which made aggressive measures unnecessary. It is an ecosystem service provided naturally in a biodiverse landscape.

Soil: The first signs of soil coming to life are the colour and texture; it has progressively darkened with humus, is moist, loose, and crumbly. It feels slippery to the touch with good aggregation, a beneficial environment for micro- and macro-organisms. Earthworms, once scarce, are everywhere. Fine hyphae interweave with the roots—signs of mycorrhizal fungi. Plants grow deep, strong, and disease-resistant, requiring minimal intervention.

Our fresh produce tastes better and has a longer shelf life. On a bright winter evening in the early years of Anemane, while our sons were rolling in the sand pit, our staff member Maya and her husband proudly offered a bunch of carrots and freshly-harvested spinach—our first attempt at vegetable gardening. The carrots were gnarled and woody, and though we tried to make excuses about the seeds being bad, the spinach was as bitter as neem! Over time, the carrots turned sweeter and looked less like tree barks. And the spinach finally tasted like spinach. By the year 2016, the soil was neutral to slightly acidic, with a pH of 6.68.

Water: A notable change in this decade is that the land sustains low rainfall much better. Drought-related mortality of trees has declined, while the recovery from stress is much better, with fewer casualties even in our orchards. The percolation of groundwater is reflected in the muddy water of the well soon after rains, which gradually turns a milky blue once the silt settles. Summer is always a challenge, but the well sees us through. The borewell shaft, though disused, holds more water than before. While reviewing its viability, the images captured on the camera inserted in the shaft revealed water level at 80 feet, and an inflow from a crevice, possibly a spring, fed by seepage in the fractures. The borewell was declared to be viable and sufficient for domestic use by experts! Earlier, it was abandoned due to low output.

The bigger picture

As an extractive industry, agriculture exacerbates climate change and the loss of biodiversity due to high resource inputs (water, energy, and chemicals), deforestation, and emissions of greenhouse gases, methane and carbon dioxide. Gaia, the Earth goddess in Greek mythology, is better served by regenerative practices that are in sync with local conditions and ecology; this is our ethos at Anemane. Our proximity to the Bannerghatta National Park, an endangered scrub forest and a crucial watershed vulnerable to urbanisation, reinforces the need for a conscious, holistic approach.

Over time, the carrots turned sweeter and looked less like tree barks. And the spinach finally tasted like spinach. By the year 2016, the soil was neutral to slightly acidic, with a pH of 6.68.

We are encouraged by changes, subtle or palpable, because they manifest a shift towards a more stable ecosystem that is self-sustaining. The Gaian hypothesis recognises the Earth as a complex living system. The ‘farm-being’ is more than a patch of land. She is a symphony—rich, complex, and sublime. The melody that weaves through her inner processes is not always perceptible to those accustomed to seeing her parts. What we can sense and connect with is her soul, and thereby address the imbalances which affect her.

As eloquently expressed in Animate Earth: Science, Intuition and Gaia by ecologist Stephan Harding, a votary of this hypothesis, “The soul of a place, when entered into with the deep interest and concern that love entails, contains the quality of Gaia as a whole being… We need to give ourselves time to experience the soul of the place and through it the soul of the world, the anima mundi.”

{{quiz}}

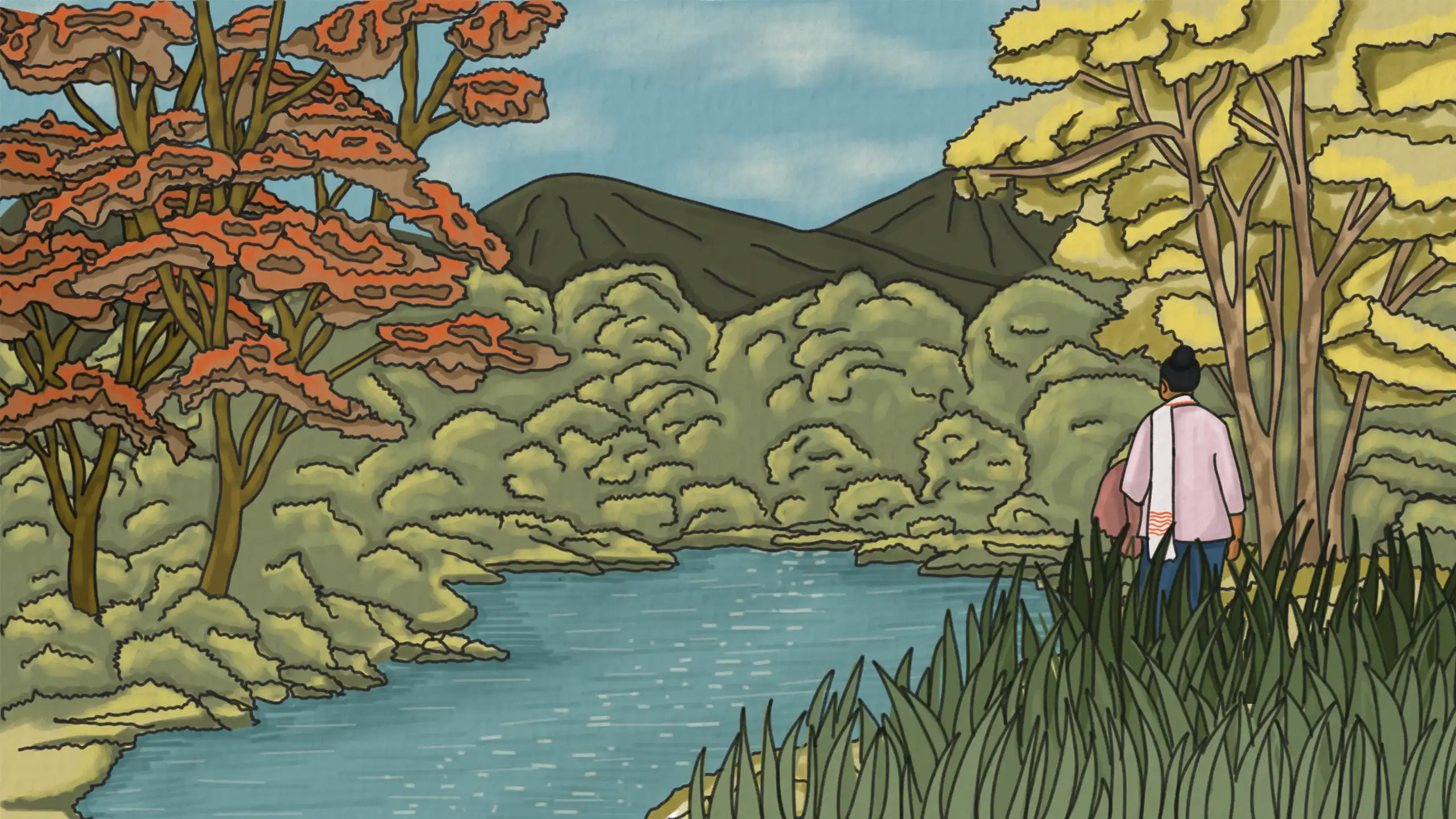

Illustration: Artwork by Khyati K

Explore other topics

References

In which decade did Ranee's journey with the land begin?

%20copy.webp)

%20copy.webp)

%20copy.webp)

%20copy.webp)

.jpg)

.avif)

.png)