Harshita Kale

|

February 26, 2026

|

3

min read

Decoding buffalo behaviour: Why the domesticated beast wallows in water

Water bodies help these hardy farm animals regulate their body temperatures in India’s hot summers

Read More

Erratic rain and rising temperatures affect yield, bean quality and farmers’ willingness to invest

Editor's Note: The planet we inherited as children is not the planet we will someday bid goodbye to. The orchestral call of cicadas in the evenings, the coinciding arrival of the monsoon with the start of the school year, and the predictability of natural cycles—things we thought to be unchanging are now at risk. An altered climate, declining biodiversity and warming oceans aren’t distant realities presented in news headlines; they affect us all in seen and unseen ways. In ‘Converging Currents’, marine conservationist and science communicator Phalguni Ranjan explores how the fine threads connecting people and nature are transforming with a changing planet.

Few aromas are as universally comforting as the scent of freshly brewed coffee, or that of freshly baked chocolate goodies. From filter coffee to fudgy brownies, two beans—coffee from Coffea arabica and C. canephora (robusta), and cocoa from Theobroma cacao—are woven into our daily rituals, cuisines, and cultures.

Yet, beneath their familiar flavours lies a sobering truth: climate change touches everything.

The story of coffee begins around 850 CE in the Ethiopian plateau, where bushes of arabica coffee grew wild. Legend holds that at this time, a goat-herd named Kaldi noticed that his flock grew unusually energetic after feeding on certain red berries. Curious, he tried them himself. Kaldi experienced a new sort of exhilaration–a high–and he shared his discovery with local monks, who began roasting and brewing these mystery beans to stay awake during long prayers through the night.

It is believed that a Sufi saint by the name of Baba Budan smuggled raw beans from Mokha in Yemen and planted them in the hill slopes of present-day Chikkamagaluru, Karnataka

By the 15th century, coffee had crossed the Red Sea into present-day Yemen (whose trading port city, Mokha, still remains the namesake for the chocolatey version of the coffee we drink), eventually journeying into Europe over the next 200 years. From there, the Dutch brought coffee to the East Indies, while French and British colonists carried it to Martinique, Jamaica, India, and Brazil (now a global coffee giant). Around the same time, it is believed that a Sufi saint by the name of Baba Budan smuggled raw beans from Mokha in Yemen and planted them in the hill slopes of present-day Chikkamagaluru, Karnataka—now known as the Baba Budangiri hills. Under colonial influence, commercial plantations of coffee flourished across Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu in the 19th century.

Over time, coffee developed a distinct cultural identity here, and continues to be drunk in many forms; a classic example that persists is the beloved South Indian filter coffee (or kaapi), made by combining a strong coffee decoction with frothy milk and sugar.

Cocoa’s lineage, too, is ancient and deeply entwined with human culture, although admittedly more bitter. The tropical cocoa tree Theobroma cacao—meaning ‘food of the gods’ in Greek—was first cultivated in the Ecuadorian Amazon around 5,300 years ago. It then spread across Mesoamerica (present day Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and El Salvador) before Europeans (hello, Columbus) chanced upon it.

As the Spanish colonised the continent in the 1500s, the ceremonial drink of the Aztec nobles—chocolatl—caught their eye. Thereafter began a reign of exploitation and coerced cultivation to expand production, which eventually extended to plantations in West Africa, another enslaved colony.

Cocoa’s history in India is relatively recent, but also colonial in origin. Introduced by the British in the late 1700s, cacao trees were mostly planted in gardens. Large-scale cocoa farming only took off in South India in the 1960s and 1970s when Cadbury established a demonstration cocoa farm in Wayanad, Kerala. Over subsequent decades, cultivation spread across Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, bringing together India’s cocoa and craft chocolate belts.

In southern India’s shaded hills, coffee and cocoa thrive under delicately balanced conditions.

Coffee planters cultivate two different varieties: arabica and robusta. As a consumer, the difference in taste emerges when you notice that arabica is smoother, has more fruity, floral notes, and a complex, bright aroma. Robusta is usually a bit stronger with a higher caffeine content, more bitter, and has more woody notes. The agricultural differences are clear: while arabica prefers the cool highland slopes at 1,000–1,500 m elevation with milder temperatures, high humidity and rainfall, robusta grows lower down between 500-1,000 m, where it’s warmer and even more humid.

This intercropping system allows smallholders (farmers with small-scale lands less than five hectares) to combine climate-sensitive, cash-generating cocoa and coffee with stable, year-round tree crops.

Cocoa loves similar tropical comforts of warm temperatures, high humidity and rainfall, and is grown in a mixed or intercropping system; the crop is cultivated under shade in coconut and areca-nut plantations, where the tall palms act as natural umbrellas. This process shares a similarity with Indian coffee farms, which also typically use agroforestry systems with two-tier shade canopies—a lower or temporary canopy, and a higher or permanent one—of silver oak, dadap, Indian walnut, red cedar, Indian rosewood, or ficus trees to protect the plants and maintain a moist and cool microclimate.

This intercropping system allows smallholders (farmers with small-scale lands less than five hectares) to combine climate-sensitive, cash-generating cocoa and coffee with stable, year-round tree crops. It offers them a diversification of income sources and a buffer in lean seasons.

However, this is not enough to combat the challenges posed by erratic weather.

Globally, the cocoa and coffee sectors are both grappling with serious climate-driven setbacks and shrinking suitable areas for production.

Arabica makes up around 60% of global coffee production, and just for context: an estimated 2.25 billion cups of coffee are consumed each day worldwide! Coffee contributes to the economies of over 70 tropical nations, supporting more than 125 million people globally across over 12 million farms; 95% of these are held by smallholders. Cocoa, similarly, is cultivated by about 6 million farmers globally, 90% of them being smallholders.

Climate change, increased temperatures, and erratic rainfall are already affecting growth and yields for both coffee and cocoa. Declining global yields of coffee—around 20% in Vietnam and 16.5% in Indonesia, both key producer countries—and cocoa (13%) inflated the prices of both commodities to an all-time high in 2024—high rates that could still not make up for the losses incurred by growers.

Projections show that by 2050, regions climatically most suitable for growing cocoa (like the Ivory Coast that supplies 45% of the world’s cocoa) and coffee (key hotspots in Africa) could both shrink by 50% because of unprecedented climactic patterns. In this scenario, cultivation could benefit from a shift to higher altitudes and away from the tropics as the minimum temperatures in these cooler areas increases. Indeed, in parts of the world, farmers are already taking arabica cultivation to higher altitudes to avoid heat-related losses.

Robusta, being the more robust variety as the name suggests, is emerging as an attractive alternative to the more climate-sensitive arabica—for both farmers and companies. However, historically assumed to withstand a broader and higher temperature range than arabica, robusta has recently been found to be more temperature-sensitive than previously thought. With a narrow optimal range somewhat similar to that of arabica, every 1°C increase in temperature beyond the range can result in yield declines by around 14%—significantly diminishing the temperature advantage. It is also more sensitive to lower temperatures outside this range. Furthermore, while robusta is drought-tolerant (not resistant), prolonged and severe droughts have resulted in farmers in Vietnam shifting to cultivating fruits for survival. So, while it is definitely a more resilient option, robusta is not immune to climate change and market dynamics in the long run.

Robusta, being the more robust variety as the name suggests, is emerging as an attractive alternative to the more climate-sensitive arabica—for both farmers and companies.

Market viability is another challenge. Arabica is preferred for its milder, less bitter, nuttier flavour profile, often the only component of specialty and premium coffees. Robusta, with its bitter, woodier and stronger flavour profile finds fewer takers and is considered of lower quality, posing a potential challenge for its mainstream adoption.

Similarly, cocoa yields suffered significantly with prices hitting an all-time high in 2024, highlighting a concerning reality that could make chocolate unaffordable. Non-cocoa alternatives that replicate the texture and flavour of cocoa have existed for a while, but the incentive to switch to them has only cropped up in recent years. Substitutes like chicory roots and carob, a legume touted for its nutritional benefits, are already being used to reduce or replace cocoa. While this alters the flavour profile of the chocolate, the differences are barely noticeable by many—a fact trumped by the many health benefits offered by carob, along with its affordability. Indeed, carob could well be the ‘robusta’ of the cacao world, potentially facing the same challenges of perception and mainstream acceptance.

Also read: Omega-3 fatty acids: The hidden costs of ‘health’ to our seas

Climate change is exerting multifaceted pressure on India’s coffee and cocoa sectors as well, especially across the Western Ghats.

Coffee is especially susceptible to rainfall variability during the flowering and post-flowering stages, and irregular or heavy rains damage flowers and fruit set (formation of fruit from the flower). Significant fluctuations in yield have been recorded over the past three decades across India’s coffee belt already. Long-term observations confirm that unpredictable monsoons can upset the delicate synchronisation of flowering and pollination, and ultimately impact yield and quality of coffee berries. In fact, local case studies report that extreme rainfall events—such as 30 inches of rainfall in a single day—have caused up to 50% losses in some coffee areas across southern India. Coffee planters in this belt identify erratic weather and climate change as the biggest challenges, followed by water scarcity (for irrigation) and increased pest attacks.

Though the two-tier agroforestry system reduces heat stress and stabilises microclimates, it cannot offset large-scale warming. Yields at agroforestry coffee farms in Karnataka and Kerala were found to decline sharply due to rising maximum temperatures and erratic rainfall. Moreover, they are projected to further drop by another 10–20% if global average temperatures rise by 2°C above pre-industrial levels—a reality that is not far off, since we are already dangerously close to breaching the 1.5°C average.

Climate change is not always quantifiable or linear. A seasoned farmer’s keen eye observes subtle changes not evident to us.

Largely confined to the same southern belt in India, cocoa also depends on consistent rainfall, high humidity, and moderate temperatures. Climate change is not always quantifiable or linear. A seasoned farmer’s keen eye observes subtle changes not evident to us. Over time, cocoa farmers in Pollachi, Tamil Nadu observed rising temperatures, erratic and declining rainfall; shortened monsoon periods translated directly into falling yields and deteriorating cocoa bean quality. Warmer temperatures and prolonged dry spells are known to cause moisture stress and a drop in flowers. They also lead to smaller pods (fruits) and beans—because of accelerated development—and variations in the fat content of the cocoa bean, which can further affect the flavour profile. Additionally, increased heat and higher exposure to light can negatively affect the concentrations of secondary metabolites in coffee that determine its quality (and thus, economic value), causing a shift in sensory characters like acidity, aroma, flavour, and ‘balance’.

For both crops, erratic climate has also made pests and disease outbreaks more frequent and severe, with emerging outbreaks of newer diseases. Outbreaks of swollen shoot virus and black pod fungus in cacao, and fruit, stalk, and root rot and borers in coffee further affect productivity, driving up prices due to falling yields.

The problem extends beyond just the crop. Socioeconomic challenges plague farmers, especially those who operate smallholdings with limited irrigation infrastructure and funds. While some farmers have responded with local adaptation strategies such as shade management, mulching, and adjusted irrigation, these efforts are fragmented and insufficient. Few have access to training or technical guidance on climate adaptation, and institutional support does not reach all those who need it.

For many small-scale growers in southern India, coffee and cocoa are vital sources of livelihood. India’s total coffee production currently stands at 4,03,000 tonnes (1 tonne = 1000 kg), with Karnataka leading the way, contributing roughly 70% of this output. India exports around 80% of the coffee it grows—a major source of revenue for the smallholders in the sector.

The clear downward trend in income from cocoa and coffee cultivation has also resulted in some smallholders considering transitioning to other crops like coconut or areca-nut, fruits, or pepper.

By comparison, cocoa production is around 27,000 tonnes, but India is set to capitalise on that sector. The global 2024 cocoa price surge, driven partly by climate shocks in West Africa, has somewhat benefitted Indian growers in the short term. However, the very factors that caused massive crop losses in West Africa threaten India’s cocoa belt as well, in the long term.

As rainfall becomes less predictable, irrigation and labour requirements rise—increasing production costs in both sectors. At the same time, input costs for fertilisers and pesticides to combat increasing infestations are rapidly soaring, further compressing farmer margins. Export-dependent coffee, being a larger commodity, has been hit harder. Increasing debt, erratic weather and failing yields have driven coffee farmers to either abandon their farms or die by suicide.

The clear downward trend in income from cocoa and coffee cultivation has also resulted in some smallholders considering transitioning to other crops like coconut or areca-nut, fruits, or pepper. These are perceived to be less climate-sensitive and resource-intensive—and thus, financially more viable in these changing times.

Also read: Bugging out: Why declining insect populations in India spell doom for agriculture

Agroforestry—the practice of cultivating coffee or cocoa beneath taller shade trees—remains one of the most effective strategies to buffer these crops against climate extremes. Shade canopies moderate soil temperature, reduce evapotranspiration, and improve soil organic matter, while providing secondary income from timber, fruit, or inter-crops such as pepper and cardamom. These strategies are already widely practiced in the cocoa-coffee belt. In fact, agroforestry systems are like small ecosystems on their own: the diverse, native shade trees offer refuge to birds, small animals, and multiple insects. Even as this system is not completely resistant to climate change-induced problems, it remains the best of a small pool of potential strategies.

Government-run crop improvement programmes are developing resilient coffee and cocoa varieties and hybrids. This year, the Central Coffee Research Institute (CCRI) is introducing new pest-resistant coffee varieties to improve yield and pest resistance, while the Kerala Agricultural University (KAU) has been working on developing stress-resilient (drought, heat) cocoa hybrids and providing farmer training for decades. Notably, the Cadbury-KAU Co-operative Cocoa Research Project set up in 1987 is believed to be the first true public-private partnership in India.

Market mechanisms like Fairtrade, pledges of climate-smart and net-zero production by companies, and public–private partnerships to support farmers and the sectors have begun offering support and technical assistance to Indian smallholders, but these are still in early stages. Fairtrade certifications seek to make farming more equitable and sustainable through training and support, enforcing threshold environmental standards, and empowering farmers through market access. Scaling these models across India’s many, many small farms would require a systemic overhaul. Sustained gains will depend on integrating resilient varieties, better irrigation management, expanded agroforestry, farmer training and education, a supportive infrastructure for farmers, and policy incentives that link research institutions with cooperatives and credit systems. Until that change comes about proactively, many smallholders will continue to face rising uncertainty, and the consumer will eventually have to accept a cup of much bitter (and stronger) robusta coffee in the face of declining arabica.

Each bean represents the labour and legacy of farming communities whose future now depends on ecological stability. But this is somehow lost behind a brand label, its various certifications and proclamations, as well as our own habits and proclivities.

Coffee and cocoa are far more than commodities; they are cultural bridges connecting India’s tropical hills to cafés and kitchens across the country. Coffee and chocolate are emotional experiences, and marketed as such. For the more refined palate, brands are happy to offer specialty coffees and single-origin, artisanal dark chocolates at a premium. For occasions, there are assorted gift boxes and curated tasting experiences.

Each bean represents the labour and legacy of farming communities whose future now depends on ecological stability. But this is somehow lost behind a brand label, its various certifications and proclamations, as well as our own habits and proclivities.

A case in point: as I wrote this over many days, I sipped on several coffees and enjoyed some 75% dark chocolate as well as chocolate cookies. All of this, I take for granted daily (or did). For me, it is ridiculously simple: come rain, hail, or drought, there will always be comforting coffee at home, and there will always be chocolate in the stores. But, pausing and realising that in the face of erratic climate, our farmers have no guarantee of the healthy yield they need (to give me the products I want) makes me appreciate every glass of piping hot filter coffee so much more, burnt tongues and all.

Artwork by Radha Pennathur, Communication Designer & Illustrator

{{quiz}}

Changing dietary choices owing to out-migration are being challenged by genuine interest and pride in indigenous crops

The last few months have been a time of discovery for 24-year-old Saraswati Majhi, who hails from the Gond community and lives in Odisha’s Kalamidadar village. As part of a quiet, rural movement comprising two hundred young individuals, Majhi has been learning and re-learning about traditional, indigenous varieties of crops grown in her district. The factor that prompted the rise of this movement? The gradual disappearance over the last decade of varieties nurtured by Adivasi elders and forefathers for generations. “These native crops and traditional foods are part of who we are—because we are what we eat,” Majhi says, in reflection.

From the remotest corners of the Nuapada and Malkangiri districts, young adults from the Gond, Paroja, Kotia, Kondh, Chutkia Bhunjia and Paharia communities have undertaken this ambitious effort which goes far beyond learning and acquainting oneself with an agricultural past and present; it is also to reclaim and revive food systems rich in diversity, resilience, and nutrition.

Launched in 2023-24 by the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE), Government of Odisha, the Forgotten Food Pilot Project aims to restore neglected and underutilised crops to local fields and plates. These include heirloom varieties of tubers, pulses, cereals, oilseeds, leafy greens, and vegetables—foods once central to Adivasi diets, but now on the verge of extinction.

The youth also documented a wealth of wild edibles—tubers, roots, fruits, berries, mushrooms, and leafy greens—still foraged from nearby forests and woven into daily meals.

Facilitated by the Watershed Support Services and Activities Network (WASSAN), a non-profit organisation working with rain-fed agricultural communities in Odisha, the initiative places Adivasi youth at its heart. They have been instrumental in identifying, documenting, conserving, and promoting the sustainable use of traditional crops. For this new generation, the question of indigenous crops has much to do with identity, cultural assimilation, and conflicting feelings of pride and loss. Kalamidadar resident Deolal Bhunjia, who is from the Chuktia Bhunjia community, says, “I feel proud knowing the richness of what our community once grew and ate. But it’s also saddening that much of this knowledge is not recorded anywhere, and is barely recognised outside our villages.”

To bridge gaps between ancestral wisdom and present-day practice, youth volunteers organised a series of focused group discussions across villages in the Chitrakonda, Malkangiri, and Nuapada and Komna blocks. Elders—both men and women—came forward to share inter-generational indigenous knowledge, recounting local crop varieties, traditional farming methods, and seasonal dietary habits. From these discussions, detailed crop calendars were developed, mapping cultivation patterns by season and month, and linking them to cultural rituals and community life. The youth also documented a wealth of wild edibles—tubers, roots, fruits, berries, mushrooms, and leafy greens—still foraged from nearby forests and woven into daily meals. Through this intergenerational collaboration, Adivasi youth are not just preserving seeds, they’re reviving a living heritage of food, culture, and climate resilience.

{{marquee}}

In the Nuapada and Komna blocks, Adivasi youth have meticulously identified and documented a wide range of traditional crop varieties that once thrived in their villages. Among pulses, they recorded indigenous types such as laha biri (black gram), tola biri (black gram), jhain mung (green gram), chikni mung (green gram), khabra ranj semi (bean), dhab ranj semi (bean), ranj jhudanga (cowpea beans), khabra kandula (red gram), ranj kandula (red gram), and choto kandula (red gram). In the process, they have also rediscovered heirloom maize varieties, such as white and red maize, which are still grown by a few elderly farmers.

To ensure community-wide engagement, the youth leading these documentation drives have shared the health and nutritional benefits of traditional foods with friends, relatives, and neighbours—a fulfilling exercise.

This documentation effort extends beyond fields, as the youth turn their eyes to forests. Several wild tubers—kochei konda (taro root), pita konda (air potato), and sap saru (elephant foot yam)—have been listed. Also documented are traditional vegetables such as bhejri tomato (cherry tomato), kanta baigan (thorny brinjal), dhala baigan (white brinjal), katei bhendi (red colour okra), satapatria bhendi (small-size okra that starts flowering after seven leaves), gol lau (round shape bottle gourd), jhumki torei (cluster ridge gourd), and chikni torei (loofah gourd).

In each variety is a story of taste, resilience, and the deep relationship between people and their land. For instance, among the Gond and Chutkia Bhunjia communities, pregnant women traditionally eat katei bhendi, satapatria bhendi and gol lau for their nutritional value and cooling properties.

Similarly, in the Chitrakonda block of Malkangiri district, several lesser-known wild fruits and berries have been identified, along with their harvesting periods. These include char koli (cuddapah almond), sindhi koli (dwarf date palm), kusum (ceylon oak), bana bhalia (marking nut tree), ambada (Indian hog plum), podai (drooping fig), and futfutedi (wild tomatillo). Among the Paroja community, the seasonal consumption of these forest fruits and berries has long been valued for boosting immunity and maintaining good health. Several varieties of wild tubers have been documented, such as chereng konda (Wallich's Yam), kasa konda (Dioscorea puber), targei konda (hairy yam), ful sarenda konda (five-leaved yam), and sika konda (mountain yam).

“Having witnessed the diversity of our forests and fields, I feel a sense of pride,” adds Tulu Pangi, 24, from Purulubandha village. “But they ought to be recognised as cultural heritage.”

To ensure community-wide engagement, the youth leading these documentation drives have shared the health and nutritional benefits of traditional foods with friends, relatives, and neighbours—a fulfilling exercise. As Madhav Tangul, 24, of Purulubandha village, says, “It’s not merely about farming, it’s about teaching our friends and families to value the foods that have kept our communities healthy for generations.”

Youth-led initiatives have also inspired practical changes. Those with upland plots began cultivating diverse crops, while backyard kitchen gardens bloomed with more vegetables and fruits. Over a year, the diversity of crops in kitchen gardens increased from two to three varieties to six to eight, and previously fallow paddy fields were now used for pulse cultivation, making the most of residual soil moisture. “Earlier, we grew only a few crops—paddy, ragi, mustard, and maize,” explains Bimala Gollari, 22, from the Mutluguda village. “Now, households are growing nine to eleven varieties, including little millet, foxtail millet, and a range of tubers and vegetables. It’s incredible to see our plates becoming so colourful and nutritious”.

Also read: How sitafals delivered fairer pay and livelihoods for Adivasi women

The necessary urgency of the youth’s work and interventions is evidenced by the recent shifts in Adivasi diets in the region—especially among the younger generation—from a diverse, nutrient-rich palate to a one that is cereal-centric and carbohydrate-heavy. “These days, the younger generation is fond of rice, potatoes, and fried foods,” says Lilambar Majhi, a 65-year-old Gond farmer from Pethiapalli village. He explains that the widespread distribution of rice at subsidised rates under the Public Distribution System (PDS) has gradually changed food habits and reduced dietary diversity.

Another key cause is the increasing rates of migration among Adivasi youth. With limited sources of livelihood in their villages, many young people from Nuapada and Malkangiri districts migrate seasonally to cities and industrial hubs in states like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu to supplement household incomes. While migration helps families meet their financial needs, it is also bringing subtle but profound cultural changes—especially in what people eat.

“After going to Hyderabad for work, I started eating more rice and spicy curries,” says Gurubai Bhunjia, 23, from Kalamidadar village. “We don’t get millets or wild edibles there. Even when we return home, we crave and miss those flavours and continue eating like we do in the city.”

For many, exposure to urban food cultures has created new preferences that are slowly replacing traditional diets rich in millets, pulses, and foraged foods. “In the cities, we mostly eat what is cheap and filling—rice or chapati,” says Naven Gallori, 26, from Jantapai village. “When I come back home, my mother still cooks ragi porridge and leafy vegetables, but my younger siblings now prefer packaged snacks.”

Yet, amid this change, some young people are beginning to reflect on what they have already lost—and stand to lose in the future. “In the city, we eat fast, but never feel full, unlike when we ate mandia (ragi) or foxtail millet rice at home,” says Dhanu Khillo, 25, who works in a brick kiln in Hyderabad. “Now I realise those foods gave us strength. I want to grow them again in our fields.”

For many, migration has also brought an uncomfortable realisation: that their traditional foods are often viewed with prejudice. In big metropolises, millet-based dishes, wild greens, or tubers are sometimes dismissed as “poor people’s food” or “Adivasi food”. This stigma has made some young migrants hesitant to embrace their culinary heritage. “When I carried mandia pej, a porridge made from finger millet flour, rice, and maize for lunch at the construction site, my co-workers laughed and called it Adivasi food,” recalls Arjun Khillo, 23, from Purulubandha. “After that, I started eating rice and curry like everyone else.”

For many, exposure to urban food cultures has created new preferences that are slowly replacing traditional diets rich in millets, pulses, and foraged foods.

The pressure to fit into city life has distanced many from the food that once nourished them. “When I tell them I miss eating boiled tubers and leafy greens from home, they joke that it’s food for the poor. It hurts, because that’s the food that kept our ancestors healthy,” says 22-year-old Sanjita Jani, who is pursuing her college education in Bhubaneswar.

But some young people are beginning to see indigenous produce in a new light—as a source of pride rather than embarrassment. “Now I realise our foods are healthy and natural,” says Keshav Majhi, 23, who works as a construction labourer in Visakhapatnam. “In the city, everything feels artificial. When I go back home, eating mandia pej and wild mushrooms makes me feel alive again.”

Also read: For Odisha’s Chuktia Bhunjias, preservation by drying is tradition—and sustenance

Odisha is home to 64 Scheduled Tribes and 13 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, which comprise over 22% of the state’s population combined. For these communities, indigenous crops and wild foods play a crucial role in ensuring food sovereignty and self-sufficiency.

The state’s rich food heritage faces mounting challenges from an environmental perspective, too: depleting natural resources and the changing climate threaten future generations’ access to nutritious food. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), there are over 30,000 edible plant species globally, of which 6,000–7,000 have been historically used as food. Experts argue that the future of food security may well depend on the neglected crops and forgotten foods that Adivasis express concern for.

Recognising this, the DA&FE, government of Odisha, has launched the scheme ‘Revival and Sustainable Intensification of Forgotten Food & Neglected Crops in Odisha’ in 2025. The initiative aims to restore the state’s traditional crop and food culture, with a strong focus on the conservation, value addition, and marketing of such produce. Over the next five years (2025-2030), the programme will be implemented across 25 blocks in 15 districts, and will reportedly directly benefit around 60,000 farmers. “Food is more than nutrition—it carries culture and knowledge passed down through generations,” says Nivedita Varshneya, South Asia Regional Adviser at Welthungerhilfe, New Delhi. “We need policies that nourish tribal food systems and protect the wisdom embedded in them.”

Also read: The Chitlapakkam Rising story: How a Chennai community saved a lake

{{quiz}}

If the claims on the front mislead, and the nutrition panel at the back confuses, where does that leave us?

Imagine this: You’re a young adult at the supermarket, finally living on your own, trying to stock a kitchen for the very first time. You squint at the labels printed on the back of each product, but you can barely pronounce the words, let alone decipher their meaning. Tossing familiar items like bags of potato chips and ready-to-eat dumplings into your cart, you shrug and walk on towards the next shelf.

You are not alone in making these choices. The packaged foods industry in India was worth over $110 billion in 2023. This category includes household essentials like oil, salt, nuts and lentils; frozen foods; snacks like biscuits, noodles, and chips; dairy items like butter and cheese spreads—the list goes on. A recent survey by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) reveals a shift in Indian dietary habits. For both rural and urban households, the biggest share of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) now goes towards beverages, refreshments, and processed foods (notwithstanding informally packaged foods). The decade between 2011 to 2022 reflects a massive jump in these numbers—from 7.9% to 9.6% of the total MPCE in rural households; and from 8.9% to 10.6% of the total MPCE in urban ones.

Worryingly, the 2024-25 Economic Survey linked the rising consumption of ultra-processed foods (a Rs. 2,500 billion industry)—fuelled by misleading advertisements, celebrity endorsements—to nearly 32 non-communicable diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions.

If the front misleads and the back confuses, where does that leave the everyday eater?

Even before this shift in consumption habits—but especially now—nutritional labels were meant to help consumers make informed choices when buying packaged foods, helping them reduce negative health outcomes. Yet, in today’s food economy, they double as advertising: bold claims like ‘low fat,’ ‘cholesterol free,’ or ‘natural’ dominate the front, even as the fine print tells another story. This dissonance has real consequences for customers. Most Indians struggle to read or trust labels—not because of indifference, but because they are crammed with jargon, printed in tiny fonts, and overshadowed by flashy promises of health and energy. If the front misleads and the back confuses, where does that leave the everyday eater?

Before 2006, India’s food labelling was scattered. It had been regulated under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954, but labels were basic and largely focused on the name of the product, manufacturer details, a list of ingredients, net weight and expiry date. Any nutritional labelling beyond this was not mandatory.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) was set up in 2006 (yes, six decades after Independence!), and introduced the Food Safety and Standards (Packaging and Labelling) Regulations only in 2011. This was the first time that an exhaustive set of regulatory guidelines was released by a central authoritative body on food. They mandated a detailed nutritional facts panel (indicating amount of energy, protein, carbohydrates, sugar, and fat), and vegetarian/non-vegetarian symbols. The label was also required to mention ‘the amount of any other nutrient for which a health claim was made.’

In a 2013 survey conducted in New Delhi and Hyderabad, most consumers said taste, price, and brand name guided their choices.

In 2018, the FSSAI introduced the Food Safety and Standards (Advertising and Claims) Regulations, 2018. This revised version more strictly stipulated that foods must first meet specific nutrient thresholds for manufacturing companies to make claims like ‘zero cholesterol,’ ‘low-sugar’ or ‘gluten-free.’ For example, a ‘zero cholesterol’ or ‘cholesterol-free’ claim must be backed by the product containing no more than 5 mg cholesterol per 100 g (solids) or 100 ml (liquids).

Despite this, brands have had a history of coming under fire for routinely violating these regulations. Nutrition supplement powders for children promise to help them grow taller, stronger and sharper with not only negligible evidence to back up these claims, but counterintuitively, also containing additives like sugar in excess. Many packaged fruit juices also carry ‘natural’ or ‘no added sugar’ claims on the front, even though fruit juice syrups can contain as much—or more—sugar as aerated drinks. In 2020, products worth nearly Rs. 9 crores were seized by the Maharashtra Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for falsely being marketed as healthier alternatives to regular butter and dairy.

Yet, such established brands continue to hold sway over consumers because of brand loyalty and consumers’ inability to scrutinise labels. In a 2013 survey conducted in New Delhi and Hyderabad, most consumers said taste, price, and brand name guided their choices. When they did turn the pack over, they checked manufacturing and expiry dates, but rarely the ingredients list or nutrition table. Many felt that buying ‘trusted’ brands made checking such details unnecessary.

Ashim Sanyal, CEO of VOICE (Voluntary Organisation in Interest of Consumer Education), says there’s a principal dysfunctionality in the law, which allows brands to make unsubstantiated claims. “While generic phrases like ‘high in energy’ aren’t registered, brands can trademark variations of claims like ‘real juice,’ ‘100% juice,’ or ‘pure apple juice’ at the state or central offices of the Trade Marks Registry under the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPDTM). Once trademarked, other brands can’t use the exact same phrase, but it does give the illusion to customers that these are FSSAI-approved. However, in reality, these are statutory bodies with little knowledge about food regulation,” Sanyal says.

The loophole is that brands bypass nutrition regulations by embedding these terms in trademarks, which are governed by laws pertaining to trademarks, not food safety. “Only if a regulator happens to inspect a product (among the thousands launched everyday) that is in violation, then action can be taken.”

Bejon Mishra, founder of Patient Safety and Access Initiative of India Foundation (PSAIIF) and a former FSSAI member, confirms this misguided faith. A Consumer Welfare Fund, set up by the central government and intended to support ministries working on consumer awareness and redressal, lies largely idle. “State governments do not issue utilisation certifications if and when they use these funds, which is why the Centre refuses to further allot money. Ministries work independently, and consumer empowerment lies by the wayside. Instead, the [food and beverages] industry at large is cajoled, with their stakeholders dominating regulatory meetings,” Mishra says. Different regulatory bodies assess different parameters of food production, regulation and distribution–and work in silos.

Also read: Add crisis to cart: Why instant delivery and antibiotics don't mix

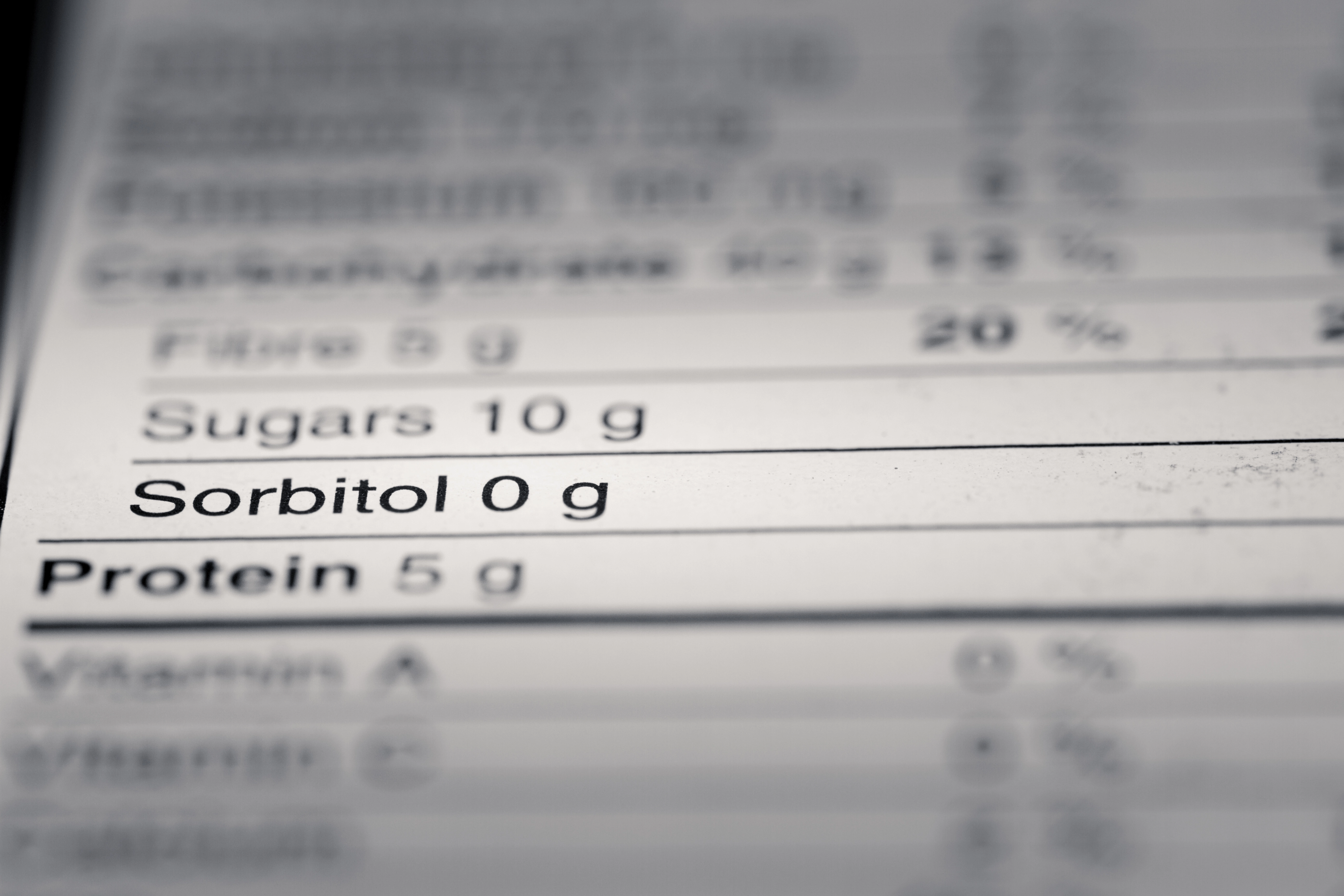

The nutrition fact panel on the back of the product may have become a government mandate over the years, but the panel, combined with other elements, is filled with technical lexicon that makes it close to impossible for the lay consumer to discern. Even literate consumers living in cities cited a myriad of reasons for not pausing to peruse the table: the information was too dense and packed with jargon, the fonts too small, and the nutrients so unfamiliar that they were intimidated and demoralised.

Mumbai-based nutritionist Aditi Prabhu says that clients who often believed they were eating healthy were dismayed when they realised what the nutrition tables actually said. “I start with the basics and ask them to look at the ingredients list first—the shorter this list, the less processed it is,” Prabhu says.

Brands may include claims like ‘low-sugar’ on the front of the pack, in bold, intended to make consumers pick up the product. However, the panel at the back may reveal that it is high in other components—sodium, saturated fats, and other additives and preservatives. Instant soups and ready-to-eat mixes often fall into this category: marketed as light or wholesome, but carrying an eye-watering amount of sodium in a single serving.

“Brands have become very clever. They may claim there’s no added sugar. But there are over 60 types of sugars. The nutrition table might reveal aspartame, sucralose, glucose syrup, and some malt,” Prabhu adds. Similarly, a biscuit labelled ‘multigrain’ may still list refined wheat flour (maida) first, followed by sugar, palm oil, emulsifiers, and flavouring agents.

Even when people make the effort to decode the nutrition table, they often walk away with incomplete or only partially-understood information. As one consumer puts it in the 2013 survey, “Nutrition facts are there on labels…when buying for my father or mother…I check the fatty acids composition, especially trans-fats. But frankly speaking, I do not know what they mean exactly.” Label literacy could be a potential key to food sovereignty. But this model assumes a certain kind of consumer—one who is urban, educated and can be empowered.

The loophole is that brands bypass nutrition regulations by embedding these terms in trademarks, which are governed by laws pertaining to trademarks, not food safety.

Dipa Sinha, developmental economist and professor at Azim Premji University, says that affordability plays a determining factor. “Low income groups can only afford specific food items, which are often informally packaged (for instance, fried snacks and candies that are portioned into small, unbranded packets). They don’t always have the luxury to choose a ‘healthier’ alternative. Data shows that the proportion of income spent on processed foods is on the rise even among rural and poor populations, which contributes to existing problems like malnutrition, anaemia and stunting.”

She stresses that regulation must address both access and informed choice together. “Caste, gender and occupation shape what people eat in our country, whether it is farmers producing their own food, or intra-household distribution of food (women and girl children often go hungry in houses with inadequate food). Label-based interventions are necessary, but they won’t solve India’s nutrition problem,” she says.

“With pre-packaged foods migrating to quick commerce apps, often, the ingredients list and nutrition table aren’t updated, or even visible,” Prabhu adds. With more consumers making split-second choices on grocery apps, they are likely to go by taste alone, she says.

Also read: Traceability in Indian food supply chains: Complicated by costs, lack of incentive

Consumer organisations in India have been lobbying for Front Of Package Labelling or Front Of Package Nutrition Labelling (FOPL/FOPNL) since 2014, Sanyal states.

Given that packaged food has been linked with deteriorating health, there has been a consistent push by food scientists and medical professionals to adopt FOPL—a global practice proven to reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods. The variant of FOPL that Indian consumer advocates are calling for involves printing warning labels of whether a product is high in sugar, sodium or saturated fats (HFSS), based on standardised thresholds, on the front of the packet. This makes it visible, easy to understand and immediately indicates the nutritional pitfalls of the product to a consumer.

Label literacy could be a potential key to food sovereignty. But this model assumes a certain kind of consumer—one who is urban, educated and can be empowered.

The first draft of such an FOPL was based on a star-rating system, but was shelved soon after. “Star ratings are inherently suggestive of approval,” explains Prof. K. Srinath Reddy, Founder President of the Public Health Foundation of India. Following pressure from consumer organisations, the FSSAI released a revised draft in 2022.

“About seven of us consumer organisations are representing public interest in stakeholder meetings,” Sanyal says. At the heart of this advocacy is the belief that consumers deserve clarity, not persuasion. Rather than banning products, these groups argue for clear warning labels that counter industry-devised ideas of health and make nutritional risks immediately visible. FOPL, then, is not a one-stop solution, but a proposed intervention—premised on the idea that accessible information can shift choices, at least for some consumers. These details may not be what consumers memorise. But once noticed, they are hard to unsee.

Globally, FOPL has proved successful. Chile’s black octagonal ‘high-in’ labels cut sugary drink sales by 24% in just 18 months and Mexico saw a 12% drop in junk food consumption. Visual cues incorporated in FOPL can also be more inclusive than current nutrition labels in India, which are text-heavy and printed in only English and a select few regional languages. This method seems to clearly be more favourable to consumers. Is it then stalled because of marketers and advertisers, who may have more to lose if it comes into effect?

“Marketers do want what’s best for consumers as well, but often, it’s difficult to find that sweet spot,” says Geetika Singh, Director of Consumer Research at Ipsos, an MNC in market research. “Consumers are probably not going to buy a biscuit which is 100% husk, let alone pay a premium on it. They would probably much rather buy something that has some percentage of something ‘healthy,’ and other ingredients which make it tasty.”

Singh also reaffirms how brands try to profit off of consumer ignorance. They do want to provide information, but not at the cost of their own sales. A few flax seeds or ‘multigrain’ claims often mask a product that’s highly processed and high in sodium. It’s a case of ‘you didn’t ask, we didn’t tell.’

FOPL, then, is not a one-stop solution, but a proposed intervention—premised on the idea that accessible information can shift choices, at least for some consumers.

FOPL is one way of empowering the rural, illiterate consumer, Sinha says. “There simply needs to be a symbol that warns when a product contains components that may harm your health. It could be as simple as what has been achieved with tobacco and cigarette packaging,” she says.

Who is the Indian food label really serving? As ultra-processed foods become more central to the urban and rural diet, the burden of health literacy has shifted onto the consumer—one armed with little more than brand loyalty and a hard-to-read nutrition panel. Meanwhile, the industry continues to wield disproportionate influence over what is said, shown, and left unsaid on the packet.

Efforts like FOPL offer a chance to flip the script—to give consumers not just information, but clarity and an understanding of what's on our plate. There’s a higher chance of a consumer taking an easy-to-read label into consideration when adding items to cart on quick-commerce apps—translating into better public health too. Today, transparency remains an aspiration. Enforcing a pictorial warning-based FOPL will be a landmark decision in Indian food regulation history and policy. Until that shift happens, the label will remain fine print hiding in plain sight.

Also read: Ultra-processed foods are reshaping our diets. Should we be worried?

Edited by Durga Sreenivasan, Anushka Mukherjee, and Neerja Deodhar

{{quiz}}

Documenting soil status can help spot deficiencies, and move towards sustainable practices to improve its health

Editor's note: Even before its current status as a nutrient-rich superfood, ragi has been a crucial chapter in the history of Indian agriculture. Finger millet, as it is commonly known, has been a true friend of the farmer and consumer thanks to its climate resilience and ability to miraculously grow in unfavourable conditions. As we look towards an uncertain, possibly food-insecure future, the importance of ragi as a reliable crop cannot be understated. In this series, the Good Food Movement explains why the millet deserves space on our farms and dinner plates. Alongside an ongoing video documentation of what it takes to grow ragi, this series will delve into the related concerns of intercropping, cover crops and how ragi fares compared to other grains.

Do you remember the wonder and excitement of being in a science lab as a young school student, watching a litmus paper dipped in an acid turn red? If you garden at home—on your window sill or backyard—you can recreate the same excitement, but for a purpose: the very same litmus paper test can tell you if the soil your plants are growing in is too acidic and affecting their growth.

Similarly, if you want to check for soil organic matter, just mix soil in a jar of water, shake it vigorously, and allow it to rest. The sand, silt, and clay will settle, while the organic matter will be left floating on top. These visual tests come in handy for budding gardeners, but for a farmer, exact data on soil is critical to identify deficiencies.

Soil tests give farmers a microscopic view. Think of them as health check-ups: periodically testing samples can help understand deficiencies in nutrient profile, enabling farmers to work towards replenishing it. In India, most government soil testing labs provide their services to farmers at nominal costs, making them an accessible service. All a farmer has to do is collect the sample and hand it over to the lab.

Most soil testing labs in India currently align with conventional agricultural practices. Based on soil health, the report recommends what mix of fertilisers ought to be added to the soil—similar to how tablet supplements are chosen to counter a vitamin deficiency. But soil tests offer so much more than a quick fix. The results of these tests can map the nutritional fluctuations of the soil throughout the crop cycle, and ensure that it gets replenished in a timely manner through organic methods.

For its ongoing experiments in ragi, GFM chose to plant cover crops (a mixture of legumes and oilseeds) instead of using fertilisers, which resulted in a slower and more sustained improvement in soil quality. We conducted a baseline soil test in February 2025 and then another in June 2025, to measure the changes before and after integrating the cover crops into the soil.

The soil is tested in three main categories: physical properties, chemical properties, and presence of heavy metals. The physical test checks for properties like pH (to check for acidic/alkaline soil), electrical conductivity (to check for salinity), and soil organic carbon (to check for carbon content, derived from decomposing plant and animal matter, and microbes). The ideal pH of soil is between 6.5 to 7.5 (slightly acidic to neutral). Excessively acidic soil tends to contain toxic metals, while excessively alkaline soil usually has some micronutrient deficiencies. Soils with excessive salinity can interfere with the osmotic process by which roots absorb water, and result in stunted growth. Soil organic carbon is often considered the most important metric of soil quality, as it represents the soil’s capacity to retain water, aerate soil, and support microbial life.

The chemical analysis measures the quantities of macro and micronutrients like NPK, magnesium, manganese, iron, zinc, molybdenum, and boron. The heavy metal test ensures that no traces of toxic metals like lead or chromium are detected in the soil. Testing regularly can help gauge where the soil stands with respect to these factors.

Also read: Decoding ragi’s cropping conditions: How farmers study soil, rains, and temperature

Following some ground rules ensures that the test can accurately analyse soil health. The most significant one? Don’t collect wet samples. This means avoiding testing during the monsoon months, and from water-logged areas. Wet samples are harder to mix and collect, and might alter test results by diluting nutrient concentrations. Samples should not be collected from areas surrounding a manure or compost pit, or from beneath a tree either, since those are likely to give skewed results too.

Wisdom on how frequently soil samples should be tested varies, but GFM chooses to measure them once every quarter to get a granular view of how soil composition changes with changing crop cycles. There are many factors which influence the soil composition, from the climate, to the crop being grown, to which nutrients it is likely to exchange with the soil. These regular tests also familiarise a farmer with the natural rhythms of the soil and harvest cycles, and help spot anomalies.

Also read: How cover crops sync with nature to replenish soil without chemical fertilisers

Soil samples have to be collected with great care. First, take a spade and dig a V-shaped pit. How deep you should dig depends on the length of the roots of the main crop. Ragi has an average root length of 15 cm, so GFM made a 15 cm-deep pit. Then, soil is scraped from both slopes made by the V-shape till one collects approximately 1 kg. This counts as one sample. GFM is growing ragi on 2 acres, which is divided into 4 plots of half an acre each. We therefore collected 4 samples (i.e. 4 kg of soil) from each plot. Each sample is collected from a different part of the plot to ensure diversity in the sample.

Next, these 4 samples are mixed on a flat surface, where stones in the sample are removed, and the mixed soil is then flattened into a circular shape. Then, two perpendicular furrows are made along the diameter of this circle, dividing it into 4 quadrants, lending it its name of the ‘quartering’ method. Opposite quadrants are discarded, hence reducing the size of the sample to half. The remaining sample is once again mixed, divided into quadrants, and halved. Thus, we come to an evenly mixed 1 kg sample for the first plot. This process is repeated for the remaining three plots. Each 1 kg sample is put into a white bag and labelled.

Upon sending them to the soil testing lab, these labelled bags can help farmers better understand the needs of the soil and their crop. Tests can alert a farmer to soil degradation due to chemical overuse or intensive farming, and help regulate which fertilisers they apply, and in what quantity. While the application of chemical fertilisers is not ideal, soil testing still helps nudge the farmer into more sustainable practices. In time, perhaps, they can be nudged into practicing organic farming.

Also read: How to choose cover crops: Lessons in balancing carbon and nitrogen

{{quiz}}

Despite early hardships due to gaps in knowledge, farmers persevered to gain training and change their fates

In her mid-fifties, Gwanli Devi bends over a small patch of farmland in Shama-Dana, a village of around 25–30 families in the Kapkot block of Bageshwar district, Uttarakhand, harvesting madua (finger millet) alongside six other women. September’s inclement weather has already ruined much of the harvest, and attacks from monkeys, birds and wild boars make their work urgent. The women move quickly, trying to salvage what remains before further unseasonal rains strike.

To reach Dana, one leaves the main road at Shama and descends half a kilometre along a winding path, scattered with rough stone steps cut into the hillside. The climb back up tests one’s endurance.

Behind the women, a small polyhouse stands, and kiwi vines sag under the weight of fruits still a month away from harvest. Laughter breaks out often—sometimes at inside jokes, sometimes at government policies they say have done little for rain-fed farmers, and sometimes, at my questions.

But one thing they all agree upon is that kiwi plants have changed their lives. “Lagana, paragaṇ karna or seechna toh bahut mushkil hai. Bahot parishram karna padta hai. Par fayada bahot hota hai (Planting, pollinating, and watering are tough. They require a lot of hard work, but the benefits are great),” observes Gwanli Devi, who took up kiwi farming five years ago. Since the roughly 100 plants in her fields began fruiting three seasons ago, she has earned around Rs. 60,000 per season.

Seventy-five-year-old Lakshmi Devi echoes this sentiment about hard work and the fruit. The 100-plus kiwi plants she has cultivated over the past five to six years—about 75% female and 25% male—have done more for her income than any other regional crop in decades. “Even if planting them is laborious, they are safe from animals like monkeys and wild boars, and give us good returns. Well, at least something is good,” she notes with a wry smile, offering a chunky cucumber from her fields while complaining about the lack of infrastructure in the village.

Eight villages in Kapkot block, perched at about 2,100 metres above sea level, have seen their cropping patterns transform over the past two decades. Once dominated by millets, lentils like rajma and bhatt (kidney beans and black soybean), and seasonal vegetables such as cucumber, capsicum, and bitter and bottle gourds, the landscape has steadily shifted toward kiwi cultivation.

The fruit has become both a commercial crop and a marker of economic change, one that neighbouring villages in Bageshwar, Pithoragarh and Nainital have been eager to emulate.

Kiwi arrived in Shama almost by chance. In 2004, under the central government’s Integrated Development of Horticulture project—a precursor to the National Horticulture Mission (2005-06) and now part of the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH)—farmers from three villages, Shama-Dana, Liti and Badi Paniyaali, travelled to Himachal Pradesh to study horticulture practices.

The fruit has become both a commercial crop and a marker of economic change, one that neighbouring villages in Bageshwar, Pithoragarh and Nainital have been eager to emulate.

They returned, carrying a handful of kiwi saplings. Among them was a cousin of Bhawan Singh Koranga, then the principal of JLN Inter College in Shama, who planted two—one male and one female—on his farm. Within three years, the plants began to bear fruit. “I had always been interested in farming, experimenting with many fruit-bearing plants since childhood. When the kiwis fruited, I thought I could work in that direction,” Bhawan Singh, 76, recalls.

Envisioning kiwis as a retirement plan, a year before he retired in 2009, he ordered a hundred more saplings, planting 50 on his own farm and distributing the rest to fellow farmers in Dana and surrounding villages. The family owns a large chunk of farmland in the village, where they grew traditional crops, mostly meant for consumption and sale in the local markets. Bhawan Singh’s persistence, despite early failures and a lack of technical guidance, eventually made him one of the most respected kiwi cultivators in the region. “Harish Singh Koranga in Liti village was also successful,” he adds.

Also read: No monkeying around on this kiwi farm

The story of the kiwi’s arrival in Shama reflects the fruit’s long journey into India. Originally known as Yang Tao or Chinese gooseberry, it was taken from China to New Zealand in 1904 by Isabel Fraser, an educationist. By 1910, the Allison brothers in New Zealand had managed to fruit it, and the emergence of commercial orchards followed by the 1930s.

In India, the first plants arrived in the 1960s at Bengaluru’s Lalbagh Garden, but failed to fruit. A second introduction in 1963 at Phagli in Shimla (then under the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, now National Bureau of Plant Genetics Resources) succeeded only in 1969-70, laying the foundation for the fruit’s eventual spread in the Himalayan mid-hills. Commercial cultivation has gathered pace only in the last three decades, with Himachal Pradesh pioneering the crop. Today, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Sikkim lead in production.

The most widely grown cultivars—Allison, Bruno, Hayward and Monty—can all be traced back to a single seedling that first fruited in New Zealand in 1910. Horticulture scholars note in the book, Temperate Fruits–Production, Processing and, Marketing (2021) that the kiwi’s adaptability, nutritional value, and market potential make it a strong candidate for crop diversification across India’s mid-hill regions, the gentle hills between plains or low valleys and high-altitude hills.

In Shama and its neighbouring villages, one of the biggest challenges in the first decade of adopting the kiwi was that farmers struggled to harvest enough fruit. Many did not understand the basic technicalities of cultivation, even though government officials were distributing saplings in the early years.

At Shama’s main market, 46-year-old Draupadi Devi recalled receiving two kiwi saplings about 11 years ago under a government scheme. She planted them on either side of her general store, unaware that kiwi calls for careful management of male and female plants for pollination, proper spacing and support structures like trellis bars or pergolas.

In the years that followed, the male vine thrived, and the female wrapped itself around a pillar, but neither bore fruit. “It was only three years ago that someone told us about grafting the male plant. We tried it, and this season we finally saw two fruits, though one was lost in a hailstorm,” she says, pointing to the lone kiwi still hanging outside her shop.

The kiwi’s adaptability, nutritional value, and market potential make it a strong candidate for crop diversification across India’s mid-hill regions, the gentle hills between plains or low valleys and high-altitude hills.

Bhawan Singh laughs at the story, admitting that until 2014-15, he and many other farmers were making similar mistakes, repeatedly. “We kept receiving guidance, but only in fragments. There was a dearth of technical knowledge in the state, among scientists, bureaucrats, or anyone else. As a result, the fruits were of poor quality, and we couldn’t fetch fair prices.”

He had approached several institutions in Uttarakhand for support—including the G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology in Pantnagar, ICAR-Vivekananda Parvatiya Krishi Anusandhan Sansthan in Almora, and the horticulture department—but the information remained piecemeal. “The most useful guidance came from Dr Kamal Pandey at the Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Bageshwar. But nothing was enough to make kiwi cultivation profitable.”

Driven to find a solution, principal Bhawan Singh pushed for more details, often approaching officials. At the time, the Jalagam Vikas Pariyojana (Watershed Development Project), Gramya II, was active in the state. In 2018, 14 farmers were sent to Himachal Pradesh for a three-day training at Dr Y. S. Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry in Nauni, Solan, under the project. They returned with the technical skills that finally gave kiwi cultivation in the region a fighting chance.

On their farm in Shama-Dana, 38-year-old Nandi Koranga—Bhawan Singh’s daughter-in-law—walks through sprawling kiwi plantations spread across more than 1.5 acres of land, with over 700 trees, lined with water drips, t-bars and polyhouses nurturing saplings at different stages.

In the paper, Kiwifruit–A High Value Crop for Hilly Terrain, H. Rymbai and colleagues from the ICAR Research Complex, Umiam, report that the kiwi fruit grown in India’s hilly regions is largely free from major insect pests and diseases, likely because it is not cultivated in dense clusters. This makes it a promising organic and eco-friendly crop, well-suited to Himalayan conditions. The authors note, however, that temperature remains the key limiting factor, as kiwi requires about 700 to 800 hours of winter chilling for optimal yield.

We kept receiving guidance, but only in fragments. There was a dearth of technical knowledge in the state, among scientists, bureaucrats, or anyone else.

When Nandi begins talking about kiwi, her excitement is visibly palpable. She dives into minute details, “Hayward is sweet and tangy, Bruno is more mellow, Allison has soft, spiky skin; shapes vary too—long, cylindrical or round. And harvests can fluctuate wildly. A mature, 7-8-year-old plant can yield over 1-1.5 quintals of fruit in a good year,” she says, adding that the fruit has transformed the lives of the entire village. An average plant yields around 40-50 kg, some exceeding over a quintal.

“Every family now knows how to plant, pollinate and care for kiwi. On our farm alone, the fruit has created opportunities for 25–30 families each season. It brings steady income and is far less prone to pests than traditional crops. For us, it has become a sustainable approach to look at and practice farming,” she says.

Also read: How lemon groves turned Manipur’s Kachai into a citrus empire

The training received in Himachal was just the start; it spurred collective action as farmers lobbied elected representatives, eventually leading to the launch of the Uttarakhand Kiwi Mission in 2021, under which farmers received an 80% subsidy on inputs (now reduced to 70%).

In Shama, the momentum translated into the creation of a Growth Centre. Established in 2019 under the same Gramya Watershed Project, the Centre became a hub where cultivation and processing could be pursued systematically. Before reaching markets, the fruit passes through a grading process: large, uniform kiwis above 75 grams are graded A and fetch premium prices; mid-sized, slightly blemished ones are tagged B for local markets; and the smallest, misshapen fruits—C-grade—are utilised for processed food items like juice, jam, pickles or candies.

On their farm in Shama-Dana, 38-year-old Nandi Koranga—Bhawan Singh’s daughter-in-law—walks through sprawling kiwi plantations spread across more than 1.5 acres of land, with over 700 trees, lined with water drips, t-bars and polyhouses nurturing saplings at different stages.

“For the first few years of production, we didn’t know what to do with the C-grade produce. Now, we process those fruits,” says Nandi, handing over a few masala kiwi candies that became very popular in the local market last year. “We realised that while we could manage fruit production, the smaller-sized fruits could be processed into by-products, giving us double the advantage,” Bhawan Singh says.

To build this capacity, the Gramya Watershed Project was approached again to send the farmers to Himachal for hands-on training in food processing. When they returned, a processing unit was set up in the Growth Centre building, complete with machinery and training for farmers from eight surrounding villages. Bhawan Singh later started another unit on his farm.

Rajendra Singh Koranga, the president of the Centre since its inception, recalls how many feared the Centre would collapse once the project ended in 2022, “as it happens in most cases when such projects end in three, four or five years.” But he is proud of the youngsters in the region, who came together to keep it alive, noting that “out-migration here is lower than in other parts of Uttarakhand because [we] are doing well.”

The younger generation’s commitment to the fruit’s cultivation took shape in the form of a cooperative society—the Danpur Kisan Ekta Autonomous Cooperative—with 500 farmers from eight nearby villages (Shama, Liti, Badi Panyali, Ramadi, Bhanar, Naukudi, Hamti Kapri and Dulam) and 11 board members. “Having a centralised Growth Centre makes it easier for organisations to reach out to farmers in groups. For instance, when the Goat Valley Project reached our region, they contacted us directly, and we took it forward,” says Dheeraj, a local in his late twenties who manages marketing and new initiatives at the Centre now.

“It has also become a platform where we can experiment. Some villages grow good rhododendron, so we learned to process that. Ramari’s strength is in Malta cultivation, Dulam Patti’s in strawberries—we are working with all that. We are also expanding into dairy, beekeeping and more horticulture produce,” explains Dheeraj, adding that the openness of villagers to new ideas has encouraged them to take risks beyond kiwi in the last few years.

Even if traders ignore them, they travel to village fairs with the products. Now and then, the persistence pays off, too. At the Gail Patal Mahotsav in Kanauli in 2024, they found buyers from Delhi and Noida who have now become regular customers.

Even if traders ignore them, they travel to village fairs with the products. Now and then, the persistence pays off, too.

For both Bhawan Singh and the Centre’s Rajendra Singh, diversification is essential to reduce dependence on a single crop amid climate and other risks, such as soil erosion and changing market demands. And thus, they are continuously experimenting with apples, strawberries and other crops.

However, Bhawan Singh remains confident about the kiwi’s future even now. “The demand is huge, and only a fraction is met locally in India,” he observes.

The data backs him up. A 2022 MDPI study estimated that India met only a quarter of its fresh kiwi demand through domestic production, with 75% imported. Imports have risen steadily, touching $63.7 million in FY25—a 25% jump from the year before. Chile, aided by a preferential trade agreement, remains India’s largest supplier, though imports from New Zealand have more than doubled in value.

The Uttarakhand government has recognised the gap in production and demand. In September 2025, the government announced a ₹800-crore Kiwi Mission to expand cultivation across 3,500 hectares of hill districts, along with plans for a study tour to Arunachal Pradesh and the setting up of a nursery in Bageshwar.

Dheeraj, standing alongside four other young farmers, voices the next aspiration. “We now want a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for the Bageshwar district’s kiwi. It will be crucial for us.”

Also read: How Jalgaon farmers weather storms to make it India’s banana capital

{{quiz}}

Timed to mill shifts and featuring generous proportions, these meals signified sustenance and community

A crucial chapter of Mumbai’s storied history is the era when it was a textile hub—one where mill workers spun the city’s commercial fortune on their spindles and looms. From the mid 1850s, mills sprung up across the then-suburbs, stretching from Byculla to Parel, forming the city’s industrial heartland. This area came to be known as Girangaon, quite literally meaning ‘textile village.’

Every day, for more than a century, mill workers would trudge to their shifts at the crack of dawn. The city’s native population was not enough to fuel the requirements of labour, for there were around 200 textile mills by the early 1900s. These hungry mills called out to migrants from the interiors of Maharashtra—Kolhapur, Satara and Sangli, to name a few districts, as well as along the coast of the Konkan.

Most mill workers lived in chawls, in small one-room tenements known as kholis. Chawls were low-cost buildings meant for communal living, constructed for the working class in a rapidly growing city, and characterised by shared use of amenities like bathrooms. They were cheap accommodation, and sometimes one kholi housed as many as 20 people, who worked in shifts. Even a century ago, Mumbai was an expensive city, and mill workers typically left behind families in their native villages and towns.

Many of these establishments set up in the 19th century and early 20th century were run mainly by women.

But what did these workers do for their everyday nourishment and meals, to fuel hours of back-breaking labour? Since the chawls were cramped, workers could not cook in their rooms. This was the catalyst for the emergence of the khanaval (common kitchen) culture in Mumbai—small establishments that would serve home-styled food to migrants living far away from home. “Most mill workers depended on khanavals for their everyday meals,” says Dr. Mohsina Mukadam, food historian and Associate Professor of History at Mumbai’s Ramnarain Ruia College. “Many of these establishments set up in the 19th century and early 20th century were run mainly by women,” she adds.

Khanavals quickly became popular for their affordability and convenience; they priced their meals keeping in mind the income and socio-economic conditions of their diners. “The prices would typically start at 3 annas, going up to 8 annas for a monthly subscription of services,” Dr. Mukadam says. The prices would also fluctuate depending on what was being served—“for instance, a ‘special’ beverage like buttermilk, or an extra guest would warrant paying extra,” she adds. Time and location were determinants, too. “At one time, khanavals in the Fort area would charge Rs. 35 monthly,” a hefty sum for the time.

Through the memories of mill workers like Suresh Ramchandra Ole, who worked at Victoria Mills in present day Lower Parel, it emerges that khanavals also offered ‘dabba’ services. “We used to get tiffins at 11 am and would finish our meals by 11.30 am sharp,” he says.

Neera Adarkar, an architect and urban researcher, talks about their spatial layout: “These khanavals were run out of rooms in chawls. Women temporarily converted their homes into a space where food could be cooked and served, and where mill workers could come and dine.” Adarkar is the co-author of One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices with Meena Menon, a book that retells the history of Mumbai’s densely populated textile district area through the testimonies of its inhabitants. At the height of their relevance, there were, “according to one count, about 650 khanavals in Girangaon” Adarkar and Menon write.

The food was basic and served on paatlas (wooden planks). “Bhakri (a flattened bread made of different grains like rice, jowar and bajra), vegetables, rice and a curry of some kind were regular items on the menu. Sweets would be served on special occasions,” says Dr. Mukadam. The appeal of the khanavals was also that they understood regional palettes and catered to their customers accordingly. “People who came from Kolhapur preferred jowar bhakris, while those from the Konkan regions liked their rice and ragi bhakris,” she adds.

A majority of the original migrant population that worked in mills was Konkani, and therefore, many Konkani khanavals sprung up in Girangaon. “A basic Konkani Taat would have a mound of rice, a bowl of sol kadhi (a pink drink made from coconut milk and kokum, with a bit of salt, and chilli-garlic paste) with a piece of fried fish, often a king mackerel (surmai). It also included a small bowl of curry, either prawn or fish, and ‘ghavane’ (rice flour pancakes) or chapatis,” writes TV personality and food writer Kunal Vijayakar.

The appeal of the khanavals was also that they understood regional palettes and catered to their customers accordingly.

Food was served in unlimited quantities, and people could take second helpings, recall the Shirodkar family, who are the current owners of the iconic Shri Datta Boarding House in Lalbaug, originally set up in 1920. In contrast, the portions today are largely fixed. “Earlier, if someone ordered a chicken thali, it came with chapati, bhakri, authentic vade (a kind of poori), a little sol kadhi (a beverage made of coconut milk and kokum), gravy, and rice. Service was different too—if a guest asked for gravy, we would simply bring a mug full and pour it into their bowls,” says Sanil Shirodkar, the newest generation to run the boarding house.

Khanavals recreated the atmosphere of home for mill workers, for whom there was little other space to experience community. They did not just function as a dining space; in One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices, the khanaval emerges not merely as a place of sustenance, but a space to meet and exchange news. “Those who came to eat would talk about their problems—we would chat. Someone would mention his wife was sick, someone would talk about how he had to build his house, that kind of talk. Those who come to eat … they have been eating here for five to six years so they’ve become family,” Indu Patil says of the khanaval run by her family.

Also read: The spice keepers of Mumbai's Masala Galli

The khanavalwalis, or the women who cooked meals, became informal postmasters and confidantes for proletariat Mumbai. Migrants would sing songs, tell stories, narrate anecdotes and talk about their village and family back home. Marathi folk singer Nivrutti Pawar says that her aunt’s khanaval also served as a discreet meeting spot for revolutionaries living underground in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Because they were constantly in hiding, her aunt exercised great caution while hosting them. Pawar remembers being asked to sing freedom songs for these guests—a request she readily fulfilled.

Apart from mill workers, students and shopkeepers also frequented these small, home-run canteens. Chinmay Damle, a food research scientist, says, "Mumbai was the examination centre for students appearing for University exams. These students typically ate in khanavals."

Taking forward the legacy of her mother-in-law Kavita, Manisha Chaudhary runs a khanaval from her home in Kurla West. “Men from mills would come and dine here—four or five at a time,” she says. Today, Chaudhary serves Satara-style chutney, jowar bhakri, rice, and dal. “After the mills shut, business went down, but rickshaw drivers and labourers still came. I now have about ten customers—3 to 4 can sit and eat, others take tiffins.”

Also read: Mumbai's Nagori dairies are a living archive of milk, migration and memory

Many early khanavals were run by Brahmin or upper-caste women and offered strictly vegetarian meals, and the names of establishments were often indicators of the proprietor’s caste—becoming a subtle way of filtering out customers. But as the migrant workforce in Girangaon grew, drawing people from the Konkan, Marathwada, Vidarbha, and beyond, khanavals began to diversify. Oral histories showcase how Maharashtrian non-vegetarian staples like fish curry, mutton, or chicken slowly entered some menus, especially in khanavals catering to non-Brahmin communities. They adapted, providing inexpensive meals suited to the religious and regionally specific and diverse migrant population.

In the 1890s, a woman named Sakhubai ran a khanaval in Girgaon. She is remembered as the first woman to do so without enforcing caste boundaries in her mess.