Murukesan has been working towards conserving the region’s mangrove cover

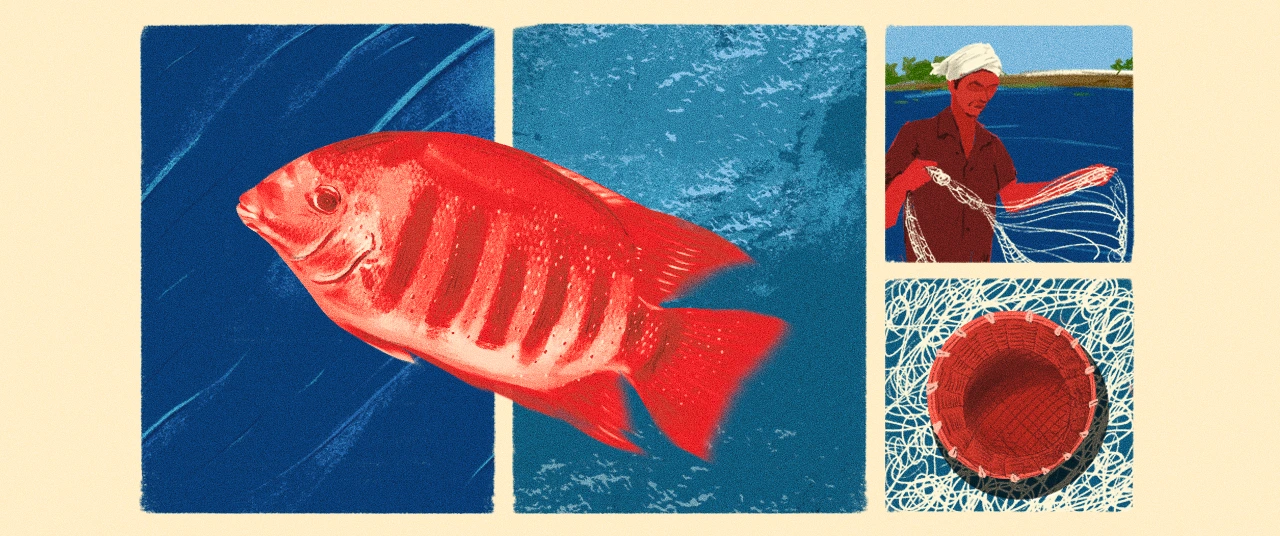

Murukesan TP wades into the backwater and disappears into it in a flash. Seconds later, he emerges, carrying in his hands a mound of blackish mud, which he deposits on the shore. This routine continues until he has collected enough of the nutrient-rich mud that will serve as the bed for his mangrove seeds at home.

Murukesan from Malippuram, a small fishing hamlet 13 kilometres from Ernakulam, has over 5,000 mangrove saplings at a small nursery attached to his 10-cent property. For over 11 years now, this fisherman has been working tirelessly towards conserving the region’s mangrove cover. Till date, he has planted more than 100,000 saplings in Elankunnapuzha, Mulavukadu, Valanthakad, Vallarpadam, Puthuvype, Njarakkal, Cherai and Kannammali regions where the mangrove population has declined drastically.

According to a 2009 study carried out by the Kerala Forest Research Institute (KFRI), of the 14 districts in Kerala, mangroves are spread over 10 districts with Kannur having the largest area under mangroves (755 ha), followed by Kozhikode (293 ha) and Ernakulam (260 ha). Over the years, as the burgeoning city began expanding its boundaries, mangrove forests were cleared.

I was born and raised here, amidst the fields and mangroves, and they have always been a part of my life.

Murukesan, 58, has witnessed this change first hand. “I come from a family of farmers who worked in the Pokkali fields here in Malippuram. I was born and raised here, amidst the fields and mangroves, and they have always been a part of my life. I remember my grandmother cooking the seeds of uppatti (avicennia officinalis) known as black mangrove for they were said to have medicinal properties,” he says. Over time, rapid urbanisation led to the shrinking of mangrove forests and Pokkali rice fields were filled up for construction.

How it all started

It was in 2013, when he had a chance meeting with an official from the Kerala Forest Department’s social forestry programme that Murukesan decided to get into active conservation. “We spoke about replanting and the idea of a nursery was born then,” he says. He soon set up a makeshift nursery at home.

In 2020, Murukesan improved the infrastructure at the nursery with the support of the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation’s fisheries-based skill development and livelihood enhancement project for coastal villages. Today, the nursery, which is built in the space around his house, is 10 metres in breadth and 40 metres long.

He builds a seed bed by creating a frame on the ground with bamboo pieces stacked close together (about eight to nine inches in height). This is filled with the fertile mud collected from the backwater. After the bed is ready, the seeds are sown and watered periodically. “If it is too sunny, I tie a thin sheet above.” Once the seeds are sown, Murukesan monitors them constantly. “I have to keep checking, remove the bad seeds and ensure they are watered,” he adds. In about three weeks, the seeds sprout two leaves and in two months, they grow up to one-and-a-half feet in height. “This is when the saplings are ready to be planted,” Murukesan adds.

Seed collection usually begins in April and extends up to May – he takes his two-wheeler and goes on a seed hunt. “I usually come back with at least two sacks full of seeds, however, this year, owing to the harsh summer, the seeds were fewer,” he adds.

Murukesan does the planting himself, too. He takes his boat out to the estuarine zones and plants the saplings close to the shore in such a way that they are not fully submerged during high tide.

The picture, however, isn’t all too rosy. Murukesan does 80% of the work, even though his family and friends chip in at times and the process is expensive. He buys bamboo, rope, sacks, and rents out a machine to cut the bamboo into pieces. Though the organisations/individuals who place the orders for mangrove saplings for planting drives pay him, most of the money is spent from his own pocket, which gets especially challenging when he isn’t able to go out fishing. But Murukesan is undeterred. “I will continue to do what I can to bring mangroves back to their former glory,” he says.

During the initial days, his neighbours saw his work as a futile exercise. They couldn’t understand why he would want to spend time and money on a relatively valueless plant. “Coastal communities often attach a nuisance value to mangroves as they are a safe haven for reptiles, mosquitos and sometimes attract otters; which are seen as pests by people living close to mangroves,” Murukesan says.

But today, things are different. Governmental organisations and private bodies procure saplings from him and he is often invited to give lectures and talks on the importance of mangroves in the region. He has won a number of awards and recognition for his conservation efforts, too. “The people around here have begun to understand my work. I have become a mangrove evangelist,” he laughs.

Even if I can create a difference one tree at a time, I would say it is a step ahead.

Mangrove tree clusters act as a natural barrier against tidal waves, storms and coastal erosion. “It was during the 2018 floods that coastal communities realised the real importance of mangroves. It can prevent coastal flooding to a great extent,” he adds.

They also sustain several marine species. Mangrove swamps serve as feeding, breeding, and spawning ground for fishes, crabs and shrimp. The inorganic nutrients from the land and decomposed leaves supply valuable organic nutrients for marine organisms. The trees, with their wide canopies, act as a sanctuary for birds.

Kochi has about 15 varieties of mangroves and Murukesan deals mostly with Rizophora mucronata (the Asiatic mangrove or bhranthan kandal in Malayalam).

Murukesan is confident that if the afforestation efforts are carried out at this rate, we would be able to witness a visible change in the next 10 years. He says: “Even if I can create a difference one tree at a time, I would say it is a step ahead.”

Explore other topics

References

.png)