Harshita Kale

|

June 11, 2025

|

10

min read

Are superfoods real—or a marketing gimmick?

Unpacking how exotic and everyday ingredients are elevated to ‘super’ status

Read More

To aid the gut’s complex ecosystem, know how to balance both

Around 2010, between ads for soft drinks and malty chocolate drink mixes, the iconic beige Yakult bottle began to appear on our TV screens. A 30-second clip raised a question which had not been asked on Indian television before: “Why should I drink bacteria?” This refrain, echoed enthusiastically in the Yakult ad, was one of the first instances of gut health being talked about in the Indian public domain—the first glimpse of the benefits of probiotics.

Probiotics are not new to us. Indians, especially, have added probiotic food and drinks to their diets for overall health since the Vedic times. It’s just that the term now had a marketable face, a name and a neatly packaged form in a tiny plastic bottle.

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics defines probiotics as "live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host." This scientific phrasing belies the millennia-old relationship humans have had with fermented foods, which are bustling with microorganisms. Long before scientists in white lab coats identified and named bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, people across cultures were cultivating bacteria in yogurt, pickles, and bread. Probiotics, the microorganisms, became a thriving industry in the 20th century, their promise bottled, branded, and sold–starting with the well known, red-capped Yakult bottles.

Probiotics have a multitude of benefits, but primarily, they improve your gut health by supporting and adding to the millions of “good” bacteria that line your gut. However, a healthy gut isn’t achieved only by adding more bacteria—it also requires you to nurture what is already present in the linings. This is where prebiotics come in the picture.

The human gut is much like a processing unit, a workplace to some 40 trillion microbial bacteria from hundreds of different species. These microscopic workers influence digestion, immune function, and even help maintain a person’s mental health. Probiotics, which are very similar to these in-house bacteria or the human microflora, are what smoothly run this ecosystem; prebiotics are the nutrients that help sustain them.

Simply put: probiotics are the organisms, prebiotics are their food.

Probiotics can be consumed by adding whole foods that house them in your diet, or as supplements. Probiotic supplements, while popular, contain only a handful of bacterial species, whereas a well-balanced gut microbiome requires a diversity. Prebiotics, on the other hand, are often misunderstood as just another supplement. In reality, this term is simply a way to describe dietary fiber–the kind found in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. While not all fibers are prebiotics, all prebiotics are fibers, and they repopulate the growth of bacteria needed for your incredibly fragile gut ecosystem.

The gut, a complex microbial ecosystem, is very sensitive to the body’s diet. It contains both “good” and “bad” bacteria. The good microbes in your gut help your body in multiple ways, uch as aiding in the absorption of vitamins and minerals. In fact, you should know that your gut is the body’s largest immune system organ, containing up to 80% of your body’s immune cells. These cells help clear out pathogens from your body daily, the good microbes help the cells filter out the harmful ones from your body and in doing so, build immunity. These gut bacteria also produce short-chain fatty acids, which, again, help your immunity and keep inflammation at bay. Mainly, it’s useful to remember: a good gut = a healthy, strong body. But the gut is also swathed in bad bacteria, which can cause digestive issues, weak immunity, inflammation and gut dysbiosis–an unhealthy imbalance of bacteria. Further, bad bacteria grow fast, especially without resistance from the good ones.

Clearly, your gut is delicate–and for it to have a diverse microbial environment, both probiotics and prebiotics are necessary.

Also read: Antibiotic overuse is turning your gut against you

A good trick is to remember that any fermented food has a lot of probiotics, because of, of course, the host of bacteria that have aided the fermentation process in the food or drink.

Also read: DIY kombucha: A simple, delicious guide to brewing

High-fiber fruits like bananas, particularly when unripe (rich in resistant starch), apples (packed with pectin, a soluble fibre), and guavas (fiber powerhouses) naturally support a flourishing microbiome. Root vegetables such as carrots and beetroots, as well as integral legumes like lentils and chickpeas, further nurture gut health. Whole grains, too, play a part: brown rice offers resistant starch, while jowar (sorghum) contributes to the thriving microbial diversity.

And these are all prebiotics!

.webp)

Probiotics help regulate the immune system and alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms, though they are not particularly effective for weight loss, metabolic health, or lowering blood sugar. Prebiotics, on the other hand, offer a metabolic advantage, with strong evidence supporting their role in reducing blood sugar levels and improving overall metabolic function.

Like probiotics, prebiotics also influence the immune system and serve as a source of fuel for intestinal cells known as short-chain fatty acids. Interestingly, despite producing these acids, prebiotics are not highly effective at relieving gastrointestinal discomfort. If dealing with yeast overgrowth or Candida infections, incorporating both probiotics and prebiotics may help. A well-functioning gut ecosystem requires not only pinpointing the imbalances but also strengthening the good bacterial populations.

The science of gut health remains a work in progress–a rabbit hole that scientists just can’t help going down farther and farther. The consensus suggests that rather than adding probiotic strains, the existing bacterial populations can be well-maintained through diet– suggesting that a shift can be made from supplement-driven solutions to the one that recognises the role of food, lifestyle, and microbial diversity.

So, should you be taking probiotics or prebiotics? As with most things related to health, is: it depends. A diet rich in fiber and fermented foods may do more for your gut than any bottle from the pharmacy aisle. But scientists do agree that a good balance of microbes is what’s key for your gut; prebiotics and probiotics both aid in this, and are complementary to each other. For a healthy gut, add probiotics; for healthy probiotics, add prebiotics. And find as much of it in whole foods as you can.

After all, what you put on your plate can offer more solutions to your body’s problems than you can imagine.

Yet it lacks policy backing and subsidy support in India

Biochar, a form of charcoal used as a soil amendment, is an ancient agricultural technique that is seeing renewed interest today. More than just burnt plant material, biochar is gaining popularity for its ability to improve soil health, enhance crop yields, and sequester carbon—thus, helping combat climate change. While it has been used for centuries in conventional farming, researchers and policymakers are now looking at its potential for large-scale application, particularly in a country like India, where soil degradation and climate change pose serious threats to food security. There is serious interest—but what are the stakes?

Biochar’s origins can be traced back 2,000 years ago, to the Amazon Basin, where indigenous communities created Terra Preta, or “black earth” by folding charcoal from low-temperature fires and organic waste material into the soil. They noticed that unlike surrounding nutrient-poor soils, Terra Preta remained remarkably fertile for years—and as scientists later studied, for centuries, thanks to the high carbon content of biochar. Similar practices have been observed in conventional Indian agricultural models, where farmers have long used charred organic matter and waste to enrich and preserve soil beds. However, with the rapid rise of industrial farming, urbanisation and chemical fertilisers, these age-old techniques are at risk of being a relic of the past.

Also read: Humus 101: Why this organic matter is crucial

Biochar is produced through pyrolysis, a process in which organic material such as crop residues, wood chips, or animal manure is burned in a low-oxygen environment. This prevents complete combustion, leaving behind a porous, carbon-rich substance. When added to soil, biochar provides several benefits, one of which is carbon sequestration–the ability to trap carbon at its most stable for centuries together. Usually, when organic matter decomposes, it releases carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. Biochar, however, locks carbon away in the soil, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and thus ultimately aiding in mitigating climate change.

Biochar is also responsible for enhancing soil fertility: it’s known to improve soil structure, enhancing microbial activity and nutrient retention. Unlike chemical fertilisers that deplete over time, biochar remains effective for years, making it a sustainable and ecologically-friendly soil amendment. Furthermore, with its porous structure, biochar helps soil retain moisture, making it especially beneficial in drought-prone regions across India. This is crucial for Indian farmers who are dependent on erratic monsoons and untimely weather conditions.

Not only is it a sustainable fix, it also doubles up as a zero-waste solution—producing biochar provides a way to repurpose agricultural waste, such as rice husks and sugarcane bagasse, turning it into a valuable resource rather than allowing it to rot and release methane, a very potent greenhouse gas.

Also read: Why the ground beneath our feet matters

India faces multiple agricultural challenges, including declining soil fertility, desertification, and unpredictable rainfall. According to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), nearly 30 percent of India’s soil is degraded. The overuse of chemical fertilisers has further exacerbated this issue, leading to nutrient depletion and soil acidification.

For small-scale farmers, biochar offers a way to restore soil health without relying on expensive synthetic inputs. In regions like Rajasthan and Bundelkhand, where soils are poor and water is scarce, biochar’s water-holding capacity could help increase crop resilience. Studies have shown that incorporating biochar into sandy soils improves yields of staple crops like wheat, rice, and maize.

While the benefits of biochar are clear, its widespread adoption in India is not without its challenges. Large-scale biochar production requires controlled pyrolysis units, which small farmers may not have access to. Low-tech kilns and community-level production models, though, could make it more accessible.

However, if we were to integrate biochar widely, we must know the constraints and implications that it carries. First, for farmers to use biochar in all their practices and make a profit from it, they must build distributed systems with low transportation requirements. One emerging concern is also that emissions of methane, nitrogen, soot or volatile organic compounds combined with low biochar yields may negate some or all of the carbon-sequestration benefits. The general agreement within the community is that though biochar is splendidly useful, there needs to be proper research on the production and application of biochar if we want to use it for both soil amendment and climate change abatement. Otherwise, we may end up doing one, but not the other.

With a glaring discrepancy among Indian farmers unaware of biochar’s benefits, the solution is multi-pronged. Government extension programs and NGOs need to play a crucial role in both producing low-tech models assisting farmers and disseminating knowledge about its application. This cannot be achieved without policy wide support, unlike chemical fertilisers, biochar lacks strong policy backing and subsidy support in India. Incentivising its use through carbon credits or sustainable farming programs could encourage wider adoption.

India’s agricultural policies are slowly shifting towards sustainable practices, with initiatives like the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) promoting organic inputs. Some pilot projects have already shown promising results. For example, researchers at IIT-Kanpur have experimented with biochar in paddy fields, finding that it improves soil carbon levels while reducing methane emissions from flooded rice cultivation.

Large-scale efforts at subsidising biochar use can revolutionise waste reduction. India generates 500 million tonnes of agricultural waste annually, much of which is burned openly, contributing to severe air pollution and the expansive blanket of deteriorating air quality, especially in states like Punjab and Haryana. In fact, biochar has been suggested as a “solution” to oft-blamed stubble burning-led air pollution.

Turning this waste into biochar could provide a dual benefit—pulling down the lethal levels of air pollution while enhancing soil health for a long, long time.

Also read: Regenerative farming: Solution to climate change?

Safer than chemical pesticide, it works in harmony with nature

Chemical pesticides may effectively eliminate pests, but their collateral damage is hard to ignore. From links to neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease to unintended harm to ecosystems, chemicals have sparked public health concerns.

As the air thickens with warnings about the damage caused by chemical pesticides, a quiet hero emerges from the Indian subcontinent: the neem tree. Often referred to as the “botanical marvel” or the “village pharmacy,” neem has interested scientists, environmentalists, and farmers.

Scientifically known as Azadirachta indica, neem is also popularly known as the “gift of nature”. Its adaptability to poor, degraded soils and its resilience in the harshest environments make it an agricultural favourite. Its uses extend beyond providing just shade or firewood. For centuries, neem has been tapped for its medicinal and insecticidal properties. Therefore, time and again, its potential as a natural pesticide has come into sharp focus, too.

The potency of neem extract is not a new area of interest for researchers. A 1992 report points out that Indian scientists jumped on the bandwagon to study the tree much after the West began to see it as a solution to the problem of modern agriculture. Starting in the 1980s, a patent controversy ensued between the researchers from the West who tried to patent neem and Indian activists who fought to protect traditional knowledge. The latter won in 2005.

Farmers have long battled the fall armyworm, a savage pest species that attacks cereals like maize. As savage as the name, the pests have caused one of the deadliest pest epidemics in the Indian subcontinent in 2018-19. The usual synthetic solutions have proven beneficial but are highly problematic as pests sometimes resist them. On the other hand, neem compounds work on the insect's hormonal system, not on the digestive or nervous systems, and therefore, do not lead to the development of resistance in future generations. Its extracts have been shown to affect nearly 300 insect species, including aphids, whiteflies, leafhoppers, and thrips, known menaces amongst Indian farmers.

Several methods were used to extract the beneficial chemicals from neem seeds and leaves. The chemicals were then tested on various crops, from cardamom to mangoes.

Also read: The 'plant' doctor will see you now

The plant’s resourcefulness as a natural pesticide is buried in its seeds, specifically the kernel, which bears an oil rich in insecticidal compounds. Neem oil contains sulfur and other bioactive components that work like a charm against pests. It can be transformed into powders, granules, and emulsifiable concentrates, creating a wide range for farmers to choose from. But no matter how you use it, neem oil requires patience. It takes four to seven days to show results, and repeat applications are often needed.

Its strength, however, lies in its versatility. It targets pests and eggs that hide through winter as a dormant spray. Moreover, timing is essential; pick a dry, calm day when the temperature is above 4°C, and avoid using it if a frost is coming.

It can be applied directly to leaves as a foliar spray, keeping pests and diseases away during the growing season. For more stubborn issues, one can try a soil drench. This involves mixing neem oil with water and pouring it into the soil, where the plant’s roots absorb it. Once inside, the neem does its thing, tackling fungus gnats, soil-borne fungi, and pests hiding in the dirt. Whether dealing with houseplants or an outdoor garden, neem oil is a simple way to protect plants.

Unlike chemicals, which kill indiscriminately, neem oil acts as an “antifeedant,” deterring insects from feeding and ultimately starving them. This modus operandi ensures that neem-based treatments target only pests while sparing beneficial insects such as bees and butterflies when used adequately. Research has consistently highlighted neem’s efficacy. In rice fields, for instance, neem oil sprays and soil amendments have proven effective against pests like the rice leaffolder (Cnaphalocrocis medinalis). The larvae’s growth and development are stunted when incorporated into their food. Neem’s reach extends beyond rice; it protects pulses, cotton, groundnuts, brinjals, okra, and even bananas.

Neem oil is a godsend for organic gardeners. A simple mixture of two teaspoons of neem oil, one teaspoon of mild liquid soap, and almost a litre of water can transform into a potent spray. This concoction repels pests and fights fungal infections like powdery mildew. With neem, gardeners and farmers have an eco-friendly ally that is biodegradable and non-toxic to humans, pets, and wildlife.

But neem’s appeal isn’t just its effectiveness; it’s also its sustainability. Unlike chemical pesticides, neem doesn’t accumulate in the soil or water. Pests don’t develop resistance to their bioactive compounds (i.e., elements found in miniscule amounts that support the fundamental nutritional needs of any living organism), which is a chronic problem with synthetic chemicals. Moreover, neem can be combined with other natural oils for enhanced potency.

But despite its many advantages, neem isn’t a band-aid solution. Its effectiveness is gradual, often requiring repeated applications to achieve significant results. It also struggles to tackle fungal and bacterial infections in plants. Yet, ‘The Wonder Tree’s’ strengths far outweigh its limitations, particularly when viewed through the lens of long-term ecological health.

Discovering neem’s usefulness as a pesticide reminds us that nature often holds the solutions to its own challenges, provided we pay attention and listen.

Also read: Natural vs organic farming: What you need to know

Inter-cropping tur and chana with cereals has been an age-old practice

For decades, conventional Indian agriculture has relied on synthetic fertilisers to boost crop yields. Urea, in particular, has become a staple, heavily subsidised by the government to keep food production steady. But this dependence has come at a cost—soaring input expenses, soil degradation, and alarming levels of water pollution.

With erratic monsoons and climate change intensifying pressure on agriculture, there emerges an alternative to fertilisers: nitrogen-fixing crops, a practice that nourishes the soil in the process of agriculture and nothing more.

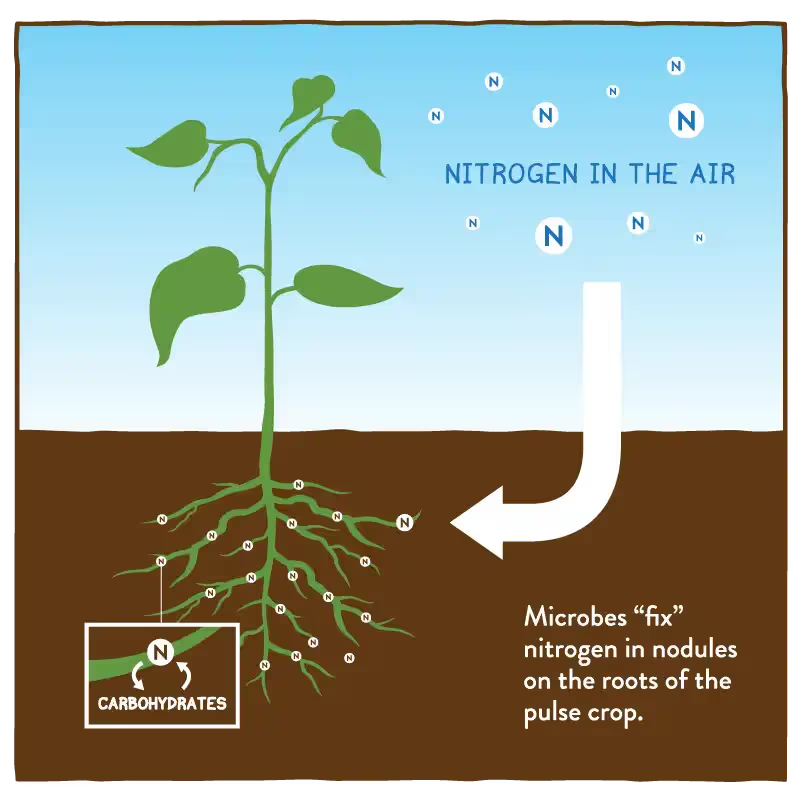

Nitrogen is essential for plant growth, but most crops can’t access it directly from the atmosphere–even though nitrogen makes up 78% of the atmosphere! Instead, plants rely on nitrogen compounds in the soil, often replenished by fertilisers. This is where nitrogen-fixing plants, such as legumes, come in. They have a natural advantage—they form symbiotic relationships with certain soil bacteria (Rhizobia) that convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2), which is in a gaseous form, into ammonia, which is a usable form for the plants. This biological process reduces the need for synthetic fertilisers, making farming more self-sustaining. In theory, it’s a perfect fix—but whether it can hold up in large-scale Indian agriculture, is the complex question that is still being explored.

One of the key challenges in relying on biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is soil health. The effectiveness of Rhizobia actually depends on soil conditions, including pH, organic matter, and microbial diversity. Afterall, the bacteria fosters a symbiotic relationship–it needs the right nourishment, in exchange for converting atmospheric nitrogen. Degraded soil due to overuse of chemical fertiliszers and intensive farming practices can limit the efficiency of nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Additionally, while legumes contribute to soil fertility, they cannot replace the high nitrogen demands of staple crops like wheat and rice, which dominate Indian agriculture.

Also read: Humus 101: Why this organic matter is crucial

Another consideration is economic viability. Synthetic fertiliszers offer immediate and predictable results, making them attractive to farmers under pressure to maximisze yields. Transitioning to nitrogen-fixing crops or integrating Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF)–a process of working with nature and without chemicals–requires time, knowledge, and investment. Encouraging sustainable nitrogen management would need policy support, farmer education, and incentives for adopting biofertilisers. But, addressing these challenges could help Indian agriculture move toward more sustainable nitrogen use while maintaining productivity.

Also read: Against the grain: Corporate to sustainable farming

Across India, nitrogen-fixing crops like pigeon pea (tur), chickpea (chana), and groundnut are already integral to traditional farming. Intercropping these with staple cereals like rice and wheat has been an age-old practice, and farmers have long realised that they improve soil fertility. Yet, large-scale adoption remains limited, especially in high-yield commercial farming. There are a few reasons for this, a significant one being: unlike nitrogen-heavy urea, biological nitrogen fixation works gradually and depends on soil health, microbial activity, and crop cycles. For small and marginal farmers, the lower input costs are a major benefit, but questions remain about whether these crops can fully replace chemical fertilisers in an economy driven by yield maximisation.

Also read: Sikkim shows how to farm without chemicals

Then, there is the fact that government policy continues to favor chemical fertilisers, with urea subsidies exceeding ₹1.31 lakh crore in 2023. This not only distorts farm economics but also disincentivises a shift towards regenerative practices. In fact, if you look closely enough, you’ll see that fertilisers are at the centre of Indian agriculture–even seed markets and agribusinesses prioritise high-yield hybrid varieties that depend on synthetic inputs. So, without policy shifts—such as incentives for intercropping or support for microbial biofertilisers—nitrogen-fixing crops will remain a secondary solution rather than a mainstream alternative for farmers.

While nitrogen-fixing crops alone may not meet India’s food demand, integrating them into existing farming systems could reduce dependency and over reliance on synthetic fertilisers. A hybrid approach—combining legumes, crop rotation, organic mixes, and judicious fertiliser use—could make Indian agriculture both more sustainable and resilient to deteriorating soil health. There have been a few attempts, too. The Biotechnological and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK (BBSRC), Department of Biotechnology, India (DBT), and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC UK) agreed to fund virtual joint centers (VJCs) to investigate the ways of managing agricultural nitrogen, and improving crop production while reducing energy inputs. One of the four centers is IUNFC (India-UK Nitrogen Fixation Center)–which focuses specifically on pigeon pea rhizobial nitrogen fixation through various creative processes, like identifying superior strains of pigeon pea and matching them with effective nitrogen-fixing rhizobia to enhance crop production and developing engineered rhizobia.

But for this movement to really be meaningful, government policies, market structures, and farmer incentives must ultimately align with long-term soil health rather than short-term yield gains.

Rebuilding humus levels can help reverse India’s soil crisis

In India's agricultural heartlands, where farming sustains countless livelihoods, the soil's hidden key to prosperity lies in humus. This dark, organic material forms when plant and animal matter decomposes and undergoes complex biological transformations. While it may seem unremarkable at first, humus is the powerhouse of soil, the element that transforms it from mere dirt into a thriving ecosystem capable of nourishing crops, retaining water, and combating the challenges of climate variability. Its importance cannot be overstated — According to the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, India experiences an annual soil loss rate of approximately 15.35 tonnes per hectare, resulting in a significant loss of about 8.4 million tonnes, especially as India battles declining soil fertility and diminishing agricultural yields with erratic weather patterns.

Humus is not just decomposed matter—it is the end product of a long process of breakdown and stabilisation, resulting in a resilient, nutrient-rich substance. Unlike raw organic matter, which decomposes rapidly, humus is stable and has persisted in the soil for centuries. It is nutrient-rich in carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, essential for healthy plant growth.

However, humus does more than simply feed crops—it fortifies the soil, creating a structure that supports life in its many forms.

Also read: Why the ground beneath our feet matters

One of humus's greatest contributions to soil health is its ability to enhance fertility. It acts as a slow-release reservoir of essential nutrients, steadily feeding plants. This starkly contrasts chemical fertilisers, which provide quick but short-lived nutrition boosts and often degrade soil quality in the long run. Humus offers a sustainable alternative, reducing dependence on expensive inputs while improving the soil’s intrinsic productivity. This is particularly critical for Indian farmers trapped in a cycle of amping up fertiliser use to compensate for nutrient-depleted soils.

Beyond its role as a nutrient bank, humus aids in water management. Its spongy texture allows it to absorb and retain large amounts of water, making it invaluable in regions prone to drought or erratic rainfall. Drought-prone regions like Maharashtra’s Marathwada and the north and central Indian province of Bundelkhand—where agriculture is predominantly rain-fed—stand to benefit immensely from soils rich in humus. By ensuring that water remains available to plant roots even during dry spells, humus supports crop growth and mitigates the impact of water scarcity on farming livelihoods.

Another often overlooked benefit of humus is its role in preventing soil erosion. In India, where unsustainable farming practices, deforestation, and overgrazing have led to the loss of billions of tonnes of topsoil annually, humus can make a significant difference. It binds soil particles together, improving soil structure and stability and preventing valuable topsoil from being washed or blown away. This is particularly crucial in a country where the loss of fertile soil directly threatens food security and agricultural sustainability.

Also read: Do-nothing farming: The Masanobu Fukuoka story

Equally important is humus’s ability to foster life within the soil. Healthy soil is not inert; it is alive with microbes, fungi, and other organisms contributing to its fertility. Humus is a steady food source for these microorganisms, creating a self-sustaining ecosystem that benefits both soil and crops. Without this microbial activity, the soil becomes lifeless and incapable of supporting healthy plant growth. This interconnectedness further asserts how humus is the foundation for robust soil health.

Despite its critical role, the Indian soil is in a humus crisis. Decades of intensive farming, monocropping, and an over-reliance on chemical fertilisers have depleted the organic matter content of Indian soils. Most Indian soils contain less than 1% organic matter, which is far below the ideal range of 3%-6%. The consequences are visible in falling crop yields, rising input costs, and soils increasingly unable to withstand climate shocks. Rebuilding humus levels is not just desirable; it is essential for the survival of Indian agriculture.

The path forward requires a shift in farming practices. Incorporating crop residues, green manures, and compost into the soil can gradually replenish organic matter and restore humus levels. Natural farming methods, already gaining traction in states like Andhra Pradesh, emphasise these methods and offer a model for sustainable agriculture. Practices such as agroforestry and zero tillage further protect the soil, ensuring that humus can thrive.

Agroforestry enriches the soil by integrating trees and shrubs to prevent erosion and boost organic matter, while zero tillage minimises disturbance, retains moisture, and sustains vital microorganisms by avoiding ploughing.

Therefore, although these changes may seem daunting in the short term to farmers, the long-term benefits—increased productivity, lower input costs, and greater resilience to climate change—are undeniable.

Humus is more than an agricultural tool; it is the essence of healthy soil. Its ability to nourish, protect, and sustain makes it indispensable in the fight for food security and climate resilience.

Also read: How one farmer purged toxic chemicals from his soil

A method that encourages mimicking nature’s processes

There is no one answer to the burdens of climate change, but many farmers agree that there is one ally: soil. The earth, which houses and nourishes crops, also has the ability to retain water during droughts, keep away pests, trap the pesky carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and grow healthier foods. But for this, you must farm not just to produce food, but also to nurture and service the soil it grows in.

Broadly, this approach to farming is understood as regenerative farming. It is not one singular method–it is a term for a range of practices that focus on conservation and rehabilitation of the soil when farming.

As a philosophical model, regenerative farming asks of us to factor in and incorporate how all aspects of agriculture are interconnected through a web of entities that grow, enhance and sustain each other. It holds no strict rule book, yet its holistic principles are rooted in addressing inequity, climate inequality and making sustainability a reality rather than a distant dream.

Small and marginalised farmers, particularly in India and other parts of the Global South, often lack secure land ownership–and this prevents them from investing in long-term sustainable practices.

Small and marginalised farmers, particularly in India and other parts of the Global South, often lack secure land ownership–and this prevents them from investing in long-term sustainable practices. Historically, land ownership in the country has remained categorically limited to upper caste and upper class households as well as wealthy landlords, leaving landless labourers in the pits of land inequity, without recourse. Regenerative farming seeks to thus root itself in addressing the inequity of high-cost fertilisers that both impoverish soil health and hold back small-scale farmers.

This method of farming aims to restore and enhance the health of ecosystems while producing food. Unlike conventional farming, which often prioritises high yields at the expense of rapid environmental degradation, regenerative farming focuses on replenishing soil fertility, promoting biodiversity, and reducing carbon emissions. Its goal is to create a self-sustaining system that benefits both nature and humanity.

At its core, regenerative farming tells you to work with nature rather than against it. It emphasises practices like crop rotation, cover cropping, reduced tillage, and integrating livestock into farming systems. These methods aim to mimic natural processes. Cover crops, for instance, protect the soil from erosion, while reduced tillage minimises disturbance to soil organisms. Livestock, when managed correctly, can contribute to soil fertility through natural fertilisation cycles. In nature, wild herbivores move across landscapes, grazing in one area and then the next. This prevents overgrazing, allowing plants to regrow and the soil to recover. Farmers replicate this by rotating livestock between pastures. Moreover, as animals graze, they deposit manure, which enriches the soil with organic matter and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen–thus reducing the reliance on synthetic fertilisers.

Crucially, regenerative farming prioritises soil health. While modern-day farming addled with chemicals has desensitised many farmers to poor soil health, regenerative farming brings it back into focus as it hopes to reverse the soil degradation that’s amassed abundantly. The word regenerative in itself suggests a sort of gentle healing–to slowly undo the harm we have done to the soil.

Also read: How a tiny Indian village brewed up a coffee revolution

The guiding principles of regenerative farming are rooted in keeping the soil surface covered with a duvet of growing crops. This reduces soil erosion and also helps the earth retain carbon from the atmosphere. Thus farmers ensure that there is no disturbance to the soil, be it through heavy ploughing or excessive fertilisers.

This duvet of crops, regenerative farming says, should be diverse. After all, monocultures aren’t organically occurring–so, the act of cover cropping can heavily improve soil health.

All of these processes aim to patiently bloom some life back into the soil, making it healthier.

The benefits of regenerative farming extend beyond the farm. But what does this mean? How can soil help a warming planet?

Regenerative farming actually holds the potential to mitigate climate change. By enhancing the soil’s capacity to store carbon, regenerative farming can act as a natural carbon sink, offsetting greenhouse gas emissions. The global effort here is to reduce carbon footprint, and this sort of farming does exactly that.

Additionally, regenerative practices enhance biodiversity by creating habitats for insects, birds, and other wildlife. Diverse plantings and minimal chemical use foster a balanced ecosystem, reducing reliance on synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. Farmers have reported economic benefits, as healthier soils often lead to higher yields and lower input costs over time. The improved water retention of healthy soils can make farms more resilient to droughts, an increasingly pressing concern, especially in countries like India.

Regenerative farming isn’t solely a respite for farmers, but for consumers as well. For consumers, regenerative farming offers the promise of healthier food. Studies suggest that produce grown in nutrient-rich soils contains higher levels of vitamins and minerals. Not only is regenerative farming a net positive for agriculturists but there could be a potential market waiting to usher in regeneratively produced food – much like organic produce.

Also read: Against the grain: Gowramma’s lessons from the land

Despite its promise, regenerative farming is not without challenges. The scientific consensus on the effectiveness of regenerative farming in sequestering carbon is still evolving. Certainly, studies reassure, healthy soil holds the potential to trap carbon, but they also caution that the extent to which soil can store carbon may be limited and heavily dependent on local and regional conditions. This indicates that regenerative farming alone cannot deliver sweeping climate benefits–there are conditions to how it should be practiced, to reap these benefits.

Another limitation is scalability. Implementing regenerative practices on a global scale requires widespread systemic changes in land management, supply chains, and agricultural policies.

In the same vein, realistically transitioning from conventional methods to regenerative practices can be costly and time-consuming, particularly for small-scale farmers. It often requires significant investments in education, equipment, and experimentation, which not all farmers can afford. However, studies have shown that while the net margin from a regenerative farming system may be lower than conventional systems in the first year, it can exceed conventional systems by the sixth year. This long-term profitability, coupled with environmental benefits, makes regenerative agriculture a viable option for Indian farmers.

Despite its challenges, regenerative farming practices form a historical corpus in the subcontinent. Techniques such as mixed cropping, crop rotation, agroforestry, and the use of local varieties have been integral to Indian farming for centuries. The traditional Barahnaja system (translating to “twelve seeds” in Garhwali) belonging to the Himalayan region is a testament to this history. Under this system, farmers would cultivate 12 or more crops together in a single field, using no chemical fertilisers. This makes sure soil erosion is at a minimum, soil health is bolstered, and an ecosystem of insects, worms, and weeds is created. The practice struck the much-needed balance between food security and ecological sustainability–something regenerative farming promises, too.

Please try another keyword to match the results