Experts say fishing targets need to be cognizant of fragile marine ecosystems

On 31 January, five members of the All Goa Small Scale Responsible Fisheries Union (AGSSRFU) set out to document illegal fishing activities in the Zuari River.

Using GPS cameras and powerful lights, they recorded trawlers fishing illegally near Dona Paula Jetty, just four kilometres from the coast.

“We submitted this evidence to the department and the police to prove that illegal fishing was taking place. The recordings were made using GPS cameras, so the longitude and all GPS data were embedded within the videos,” said Sebastiao Rodrigues, AGSSRFU’s advisor.

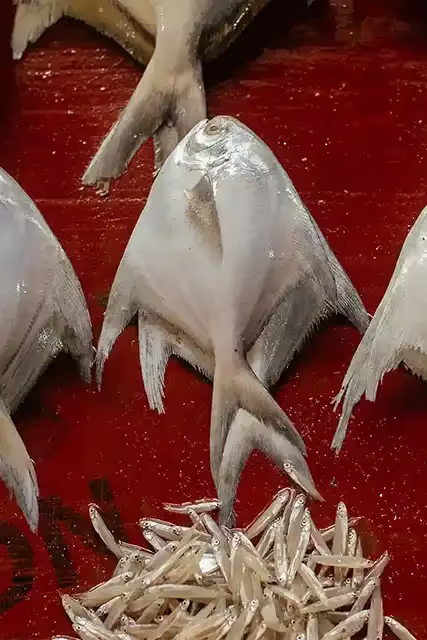

Despite being prohibited within a five-kilometer radius from the shore as per the Goa, Daman, and Diu Marine Fishing Regulation Act, 1980, ecologically harmful fishing equipment such as trawl nets and purse-seine nets continue to be used in the Zuari River.

The lack of proper enforcement has even emboldened trawlers to attack small-scale fishers.

“Although trawling has now ceased in the Zuari River due to our efforts, we still receive unconfirmed reports of a few trawlers and purse seiners engaging in such [illegal fishing] activities around 3:00 a.m. in the river,” he noted.

The union has consistently fought against illegal trawling and numerous others. There are junctures in time where it would stop—issues, including tourism encroaching on the fishers' livelihoods. Yet, given the state's lack of interest in maintaining ecological balance and curbing illegal activities, small-scale fish workers increasingly feel like they're fighting an uphill battle.

Policy dissonance

India is one of the top global producers of marine capture fisheries. Since independence, its marine capture fisheries have evolved from small-scale operations to highly mechanised ones. In 2022, marine fishing in mainland India generated an estimated revenue of ₹58,247 crore, supporting livelihoods and providing nutritional security for more than 28 million people engaged in the industry.

However, overfishing has become a growing concern in Indian waters in the past two decades due in part to the rise in mechanized fishing vessels, a trend encouraged by the Indian government to boost catch volumes. Additionally, climate change has led to declining fish stocks along India's eastern and western coasts.

The report by the Bay of Bengal Programme Inter-Governmental Organisation (BOBP-IGO) mentioned that increasing seawater temperature, ocean acidification, sea level rise, changing current pattern, cyclone intensity, ocean oxygen, and nitrate levels, and shifting fish stocks likely pose significant challenges to the marine fisheries sector, having an estimated cost of 1-2% of India's current GDP by 2050.

A 2023 study published in Marine Policy concluded that India’s fisheries policies developed over the last 75 years rarely accounted for the ecological consequences of overfishing. It analysed previous research and revealed that policies have embraced new technology to catch more fish but have been slow to acknowledge scientific evidence of declining fish populations.

The study revealed that the five states on the western coast had significant policy differences despite sharing similar marine ecology. For instance, in Maharashtra and Kerala, exclusive zones for artisanal fishing are defined by water depth, whereas in Gujarat, Goa, and Karnataka, they are determined by distance from shore. Bull trawling, a highly destructive technique, is banned in Goa and Maharashtra but remains legal in neighbouring Gujarat.

Regarding existing laws, there are no specifications for mesh sizes of trawler nets in Goa. Thus, trawlers can use any mesh size they desire.

Additionally, the minimum mesh sizes for trawlers vary considerably among these West Coast states. National fisheries policies have yet to implement a system to identify, assess, and address these discrepancies. The researchers recommended establishing effective incentives to encourage inter-state collaboration in fisheries management. “Regarding existing laws, there are no specifications for mesh sizes of trawler nets in Goa. Thus, trawlers can use any mesh size they desire,” said Rodrigues.

However, Goa has two legally approved mesh sizes for gillnets: 24 mm and 22 mm. The 22 mm size is general, while the 24 mm size is specifically for prawns and other species. These are the only two approved sizes, and anything smaller is prohibited.

Moreover, fishermen who use fish finders and have computer screens installed in their canoes and trawlers often use purse seine nets. However, purse seines are not supposed to operate within 5 km of the shore. These nets usually have a relatively small mesh size of eight or nine mm. “This situation leads to fish entering the nets, which are either discarded and dumped, including small or dead fish, directly into the river or sold as fertiliser,” he points out.

India's marine fishery has witnessed significant growth. The mechanisation of fishing vessels has led to intense exploitation of commercial marine species along both coasts and has put pressure on fish stocks, causing many species to become less abundant. The study warns that this rapid growth could lead Indian fisheries towards an unsustainable future.

Fishing ban

Every year, the Indian government imposes a 45- to 62-day fishing ban along the East and West coasts to maintain marine life and ensure healthy populations of aquatic species.

The fishing ban coincides with the monsoon season, the prime time for fish to reproduce without disturbance. The Central government enforces fishing bans in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), while state governments are responsible for setting the ban periods in territorial waters.

The primary purpose of the ban is to prevent overfishing and maintain a balance in marine ecosystems. It also helps protect fishermen from the rough seas and unpredictable weather during the monsoon season.

On the East Coast, the ban runs from mid-April to mid-June; on the West Coast, it starts in early June and ends in late July. There is a 10- to 14-day overlap in early June when fishing is prohibited on both coasts simultaneously.

Seasonal fishing bans and minimum mesh size regulations are two standard rules used in fisheries management. However, the aforementioned study published in the journal Marine Policy found that these rules often do not consider important biological information published in scientific studies.

Small-scale fishers have complained that they return empty-handed almost daily for ten days starting June 15, signaling the end of the ban period.

Debasis Shyamal, President of the Dakshinbanga Matsyajibi Forum (DMF) and council member of the National Platform for Small Scale Fish Workers (NPSSFW), which represents small-scale fish workers in the southern part of West Bengal, says that at the national level, NPSSFW demands that trawlers be banned for 120 days and motorized boats for 61 days. The NPSSFW argues that when everyone returns to the sea after the ban period, resources are depleted within 15-20 days, affecting small-scale fishers. "Small-scale fishers have complained that they return empty-handed almost daily for ten days starting June 15, signaling the end of the ban period," Shyamal points out.

NPSSFW advocates for differential management in fisheries because small fishers cannot compete with big, mechanized boats. Shyamal also notes that promoting and preserving small-scale fishers helps protect marine resources.

"Small-scale fishers are increasingly moving away from fishing activities or transitioning to work for trawlers and other big mechanized boats, indicating that resources are being depleted faster than they can be replenished," he says.

NPSSFW has repeatedly demanded a pan-India differential treatment prioritizing small-scale fishers. Shyamal explains that one reason for this demand is the increasing occurrence of cyclones and natural disasters on the East Coast. He believes that a 120-day ban on mechanized boats could also be beneficial in this context.

According to Shyamal, small-scale fishers benefit from the ban period because trawlers and other large mechanized boats must cease operations entirely.

"It has been confirmed that hand-drawn net fishers near my home [in East Medinipur district] have a significant catch during the ban period. However, soon after the ban ends, small fishers find it difficult to catch fish, and the yield decreases significantly," he explains.

The fishing ban period may be less effective in recharging marine resources. The Marine Policy study found that the monsoon fishing ban, applied to all coastal states, is not very effective because less than 40% of commercially fished species breed during the ban on the West Coast. Given these findings, changes to the regulations might be necessary.

Additionally, large, mechanized boats and trawlers do not always follow the fishing ban. Rodrigues points out that there have been reports of violations by several trawlers and purse seiners, even during the fishing ban period of June-July.

He also mentions that in his conversations with fishermen, some recommend abandoning mechanized fishing or, for small-scale fishers, avoiding using motors and resorting to rowing for fishing for at least two months. This drastic approach, he suggests, could genuinely help replenish fish stock.

"They claim that even their motors chase away fish and create sound pollution, not just trawlers," he says.

Mechanized menace

According to a 2022 report by the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), mechanized fishing vessels accounted for 82.0% of the total catch, totaling 2.85 million tonnes, out of three types of fishing crafts. Motorized fishing crafts contributed 0.61 million tonnes, or 17.0%, while non-motorized fishing crafts brought in just 0.04 million tonnes, representing 1.0% of the total landings.

This significant shift towards mechanized fishing not only impacts the marine ecosystem but also severely affects the lives and livelihoods of small-scale and artisanal fishers.

"Small-scale fishers are finding it hard to survive. They migrate from Andhra Pradesh to work on large mechanized boats operating in West Coast states like Gujarat and Maharashtra," says D. Pal, General Secretary of the Democratic Traditional Fish Workers Forum based in Rajahmundry, a city on the eastern banks of the sacred Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh.

Pal adds that the dominance of mechanized boats has increased over the past eight years due to government policies. He explains that these policies encourage the transition to mechanized fishing, but this shift does not benefit small-scale fishers. Even if the government provides partial financial support for buying mechanized boats, small-scale fishers often cannot meet the rest of the loan requirements.

"They can hardly meet their daily expenses. We can't expect them to gather enough funds to transition to mechanized fishing boats. People with more resources can afford these mechanized boats, while small-scale fishers, unable to compete with the big mechanized boats, end up working on them," he notes.

Pal also pointed out that conflicts between fishermen have escalated in Visakhapatnam. Fishermen from nearby areas, struggling to find a catch in their own regions, come close to the Vishakhapatnam area. Local fishermen in Vishakhapatnam have protested this intrusion, and in some cases, boats belonging to the intruders have been set on fire.

{{marquee}}

Surviving the ban period

Since fisheries fall under state jurisdiction, each state government decides the ban period and whether to offer any financial compensation during this time. As a result, the compensation schemes vary widely and are sometimes completely absent.

In West Bengal, there has been no allowance for the fishing ban period since 2012, when the Savings Cum Relief Scheme—which relied on contributions from the central government, the state, and beneficiaries—was discontinued. This program supported small-scale fishers during the ban period.

This year, the West Bengal government finally addressed a demand made by the Dakshin Banga Matsyajibi Forum in 2017 by launching the Samudra Sathi scheme. This scheme provides Rs 5,000 in compensation to all seafaring fishermen over 21 years old during the ban period. Even trawlers can request compensation under this scheme.

In Andhra Pradesh, all marine fishermen operating mechanized, motorized, and non-motorized vessels receive an allowance of Rs 10,000 during the ban period. However, according to D. Pal, General Secretary of the Democratic Traditional Fish Workers Forum, many small-scale fishers are excluded from this allowance.

"We have corresponded with the fisheries department multiple times over the last three years about this," he said.

Furthermore, additional eligibility criteria restrict who can receive the allowance. For instance, fishermen over 50 are ineligible, leaving many without support during the ban. If someone is over 50 but has no choice but to continue fishing, what will they do? The government doesn't even provide a pension to those over 50," Pal remarked.

Pal also noted widespread corruption, with only a few enjoying diesel subsidies—300 liters for a boat every month. Mechanized boats, which account for most of the fishing activity, tend to receive preferential treatment, monopolizing the subsidies meant for everyone. The subsidies for essential items like ice boxes, new nets, and ropes are frequently redirected towards mechanized boats.

Another source of inequity is that boats under 25 meters are considered small-scale fishers, even if they are motorized. Yet, they do not receive subsidies meant for small-scale fishers. Pal highlighted that many larger boats receiving these benefits belong to influential political leaders.

In April, fishermen associated with the Odisha Traditional Fish Workers Union (OTFWU) called for an increase in compensation during the two-month marine fishing ban from April 15 to June 14. The Odisha government proposed offering Rs. 4,500 to each family during the ban through a scheme focused on providing "livelihood nutritional support for the socio-economic background of active traditional fishery families for conservation of fisheries resources."

K. Alleya, the general secretary of OTFWU, mentioned that the ban would impact about 1.5 lakh traditional fishermen in Odisha who rely on fishing for their livelihoods. He urged the government to increase compensation to at least Rs. 15,000 per family per month during the ban. Additionally, he insisted that women involved in the fishing industry, including those who sell and transport fish, should be included in the list of beneficiaries.

In Goa, there is no allowance for small-scale fish workers during the ban period. "They survive on their savings," says Rodrigues.

Explore other topics

References

1. Herald Goa. (n.d.). Fisheries union hits out at govt for inaction on illegal fishing in Zuari river. https://www.heraldgoa.in/Goa/Fisheries-union-hits-out-at-govt-for-inaction-on-illegal-fishing-in-Zuari-river/217332

2. CMFRI (Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute). (2022-2023). Marine fish stock status of India. https://eprints.cmfri.org.in/17173/1/Marine%20Fish%20Stock%20Status%20of%20India%202022_2023_CMFRI.pdf

3. NDTV. Climate change taking toll on marine fisheries in Bay of Bengal region, says status report. https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/climate-change-taking-toll-on-marine-fisheries-in-bay-of-bengal-region-says-status-report-84549/

4. Bay of Bengal Programme Inter-Governmental Organisation. Brainstorming session report. https://www.bobpigo.org/webroot/publications/Brainstorming%20Session%20Report.pdf

5. Sivakumar, K., Subba Rao, P. V., & et al. (2023). Impacts of climate change on marine fisheries: A review. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X23003299

6. National Fisheries Development Board. About Indian fisheries. https://nfdb.gov.in/welcome/about_indian_fisheries#:~:text=The%20fish%20production%20in%20India,2018%2D19%20(provisional).

7. National Platform for Small Scale Fish Workers (Inland). https://smallscalefishworkers.org/small-scale-fish-worker-organisations/national-platform-for-small-scale-fish-workers-inland/

8. West Bengal Department of Fisheries. https://wbfisheries.wb.gov.in/official/mypage.php?id=217

9. Hindustan Times. Odisha fishermen demand compensation of Rs. 15k per month during fishing ban period. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/odisha-fishermen-demand-compensation-of-rs-15k-per-month-during-fishing-ban-period-101713172868594.html

-min.avif)

.png)