At Adike Patrike, farmers turn their experiences into valuable lessons for others

When it comes to their successful careers, farmers Marike Sadashiva and ‘Jack’ Anil vouch for an unusual source: the monthly magazine Adike Patrike.

Sadashiva converted 25 acres of his arid land into a water-surplus property when he implemented the water conservation techniques he learnt from the farm magazine in the early 1990s. Today, he owns a 10-acre organic farm and a 15-acre natural forest in Puttur, located in Karnataka’s Dakshina Kannada district.

“I couldn’t have become a successful farmer without Adike Patrike,” Sadashiva confesses. “The articles on water conservation inspired me to dig rain pits and harvest rainwater, and the results were extraordinary. Water scarcity on my land is now a thing of the past.”

Anil, on the other hand, earned a global reputation as an expert in budding jackfruit plants from leaves after Adike Patrike featured his innovative technique 20 years ago. Farmers from across the region flocked to his nursery in Puttur to graft and cultivate rare jackfruit varieties. His expertise also drew the attention of several Indian universities, which sought his guidance to promote this unique method.

In fact, working with jackfruits became so synonymous with Anil that people began to call him Jack. “I embraced the nickname with pride,” he says, reflecting on his journey.

Tens of thousands of such farmers in Karnataka have reaped countless benefits from Adike Patrike, a publication dedicated to agriculture that has been the source of diverse, insightful stories for the past 36 years.

At the helm of its editorial operations throughout this journey is 68-year-old Shree Padre, who describes himself with pride as a “farmer by profession and journalist by obsession.”

Innovation has been Padre’s hallmark. Farming and agriculture are extremely scientific, expansive subjects, and yet, he did not fill the magazine’s pages with dense research papers. Padre chose another, unique approach: he mentored farmers to become writers themselves. These farmer-journalists share their personal experiences, turning their practical knowledge into compelling stories. Today, Adike Patrike boasts a robust network of farmer-writers across Karnataka, who work the fields during the day and document their insights for the community by night.

.avif)

“That’s how we’ve lived up to our reputation as a magazine ‘for the farmers, by the farmers, and of the farmers,” Padre explains. “When farmers share their experiences, the world listens, and that’s what makes Adike Patrike truly unique.”

Also read: A man dreamt of a forest. It became a model for the world

Fight against endosulfan

Padre’s transformative interventions in this space began long before he took charge of Adike Patrike. Among other movements in the years leading up to his editorial role, he was instrumental in exposing the devastating impact of endosulfan, a highly potent neurotoxin used as a pesticide, on humans and animals in his village of Padre and the surrounding regions of Kerala and Karnataka.

Between 1975 and 2000, the public-sector Plantation Corporation of Kerala (PCK) had aerially sprayed endosulfan over 12,000 acres of cashew plantations in Kerala. The toxic residues of this pesticide spread widely through villages in the neighbouring state of Karnataka. It spread through the air, contaminating soil, water, and at large, the environment.

No one knew that the aerially sprayed pesticide was endosulfan. I was the first to confirm it from an official of the plantation corporation, whom I befriended. The government had kept it a secret until then.

The results were catastrophic: countless lives were lost, and innumerable cattle, frogs, fish, and microorganisms perished. Thousands of children went on to be born with severe congenital disabilities–including hydrocephalus, neurological disorders, epilepsy, cerebral palsy–as well as profound physical and mental impairments.

Initially, the residents were at a loss. They had no idea what brought upon this sudden and devastating suffering. “No one knew that the aerially sprayed pesticide was endosulfan. I was the first to confirm it from an official of the plantation corporation, whom I befriended. The government had kept it a secret until then,” Padre says.

The revelation sparked massive protests across Kerala and Karnataka. However, the issue failed to receive the widespread attention it deserved—until Padre intervened. He penned a detailed report, accompanied by striking photographs, and submitted it to the editor of the now-defunct The Evidence Weekly. The resulting story, sharply titled, ‘Life is cheaper than cashew,’ finally caught the eye of national and international media–but not just this: the story also brought the matter to the attention of policymakers.

Padre was working on the ground; among other things, he accompanied visiting journalists on their ground reporting trips to the affected villages. But despite these efforts, it took years before the government finally banned endosulfan. Tragically, even today, thousands of victims of this chemical’s brutal attack continue their long and arduous struggle for financial aid, rehabilitation, and access to adequate healthcare facilities.

The endosulfan interventions marked a turning point in Padre’s life.

While pursuing his undergraduate studies in Botany, Zoology, and Chemistry at St. Philomena College, Puttur, the young Sree Krishna (as he was then known) regularly displayed his cartoons on the college notice board under the pen name “Shree Padre.” His talent caught the attention of prominent publications, including Shankar’s Weekly, which featured his work.

.webp)

However, Padre considers his interview with three stalwarts of Indian cartooning–Abu Abraham, R.K. Laxman, and Mario Miranda–during an event in Bangalore as a milestone in his early career. The interview was published in 1980 in Mathrubhumi, a renowned Malayalam literary magazine edited by the late Jnanpith awardee M. T. Vasudevan Nair. “I sent the English text to Mathrubhumi, and to my surprise, they published it in three installments,” Padre recalls, holding a carefully preserved copy of the magazine.

But as he worked with the victims of the endosulfan crisis as well as journalists covering the issue on the ground, Padre’s focus shifted from cartooning to writing.

Also read: How an Alappuzha coir exporter nurtured a one-acre forest

The birth of Adike Patrike

In the 1980s, areca farmers in southern Karnataka had a crisis on their hands: areca–the betel nut–prices had tanked, and farmers’ income had consequently plummeted. This is when the Mangalore-based All India Areca Growers’ Association intervened, and decided to co-opt professionals who could help study the problem and offer solutions for the farmers. They also proposed launching a publication to educate and unite areca growers in Dakshina Kannada.

.avif)

For this initiative, they turned to Padre, an areca farmer himself, to lead the effort. And thus was born Areca News, an occasional newsletter. “It happened quite accidentally,” Padre admits. “The association’s office-bearers requested me to take charge, and I couldn’t refuse.”

Eight years later, the publication transitioned to the Farmer First Trust, which launched Adike Patrike as a monthly magazine, headquartered in Puttur.

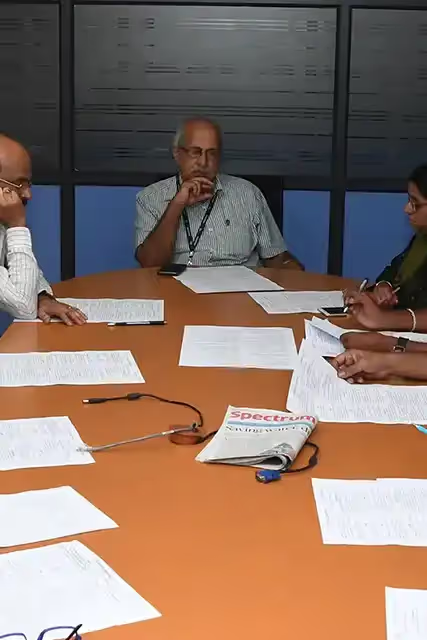

Today, if you walk into the magazine’s office, you are enveloped by its old-world charm: the antiquated tables, chairs, fans, and a fading red oxide floor take you back in time. This is where the editorial team gathers, to discuss new stories and content for its readers. When the editorial process gains momentum in the second week of every month, Padre finds his schedule getting tighter: he begins his day early, instructing workers on his farmland about manuring and produce procurement, before embarking on a 25-kilometer drive to the magazine office. Once there, he collaborates with colleagues on story ideas, identifies farmer contributors, and delegates tasks to ensure all articles are filed on time.

The magazine is printed by Codeword Process and Printers in Mangalore, 50 kilometres west of Puttur, in the fourth week of every month. Subscribers receive the finished magazine by post in the first week of the following month. “Strict adherence to the schedule has ensured that Adike Patrike has never missed an edition in 35 years, except during the COVID-19 pandemic. We distributed e-magazines to compensate for the miss,” Padre says.

Also read: How the 'makrei' sticky rice fosters love, labour in Manipur

Perennial campaigning

A hallmark of Adike Patrike is its consistent campaigns aimed at promoting underutilised fruits and value-added farm products.

One standout example is the ongoing effort to popularise jackfruit, a fruit that grows abundantly in southern India, but often goes to waste–thanks to a lack of awareness and preservation facilities. Since 2016, the magazine has published 36 cover stories on jackfruit, exploring topics like cultivation, processing, value addition, and preservation of the fruit. These stories emphasise the fruit’s nutritional richness — its high levels of Vitamins B-Complex and C, along with essential minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and iron — as well as its environmental benefits, including its ability to cool microclimates and grow without fertilisers.

{{marquee}}

Other impactful and delightful campaigns include Ba-Ka-Hu (Bale Kai Hudi), that promoted banana powder, fabric dyeing with areca nut syrup, river rejuvenation, and chemical-free vegetable cultivation. These campaigns have helped farmers understand critical issues that need their attention, and inspired them to adopt sustainable practices in their work.

Over the years, Adike Patrike has evolved into an inclusive publication that caters firstmost to its patrons: farmers. “Our focus isn’t just on adike (arecanut); it’s on farmers as a whole. We publish stories on anything and everything that broadens their horizons,” Padre says.

{{quiz}}

(Photo Credits: Sandeep S, Sreejith M, and TA Ameerudheen)

Explore other topics

References

What does 'Adike Patrike' mean?

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)